Pathology Verified Concomitant Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma in the Sonographically Suspected Thyroid Lymphoma: A Case Report△

Qiong Wu, Yu-xin Jiang, Jun-chao Guo, Yu Xiao, Xiao Yang, Rui-na Zhao, Xing-jian Lai, Shen-ling Zhu, Xiao-yan Zhang, and Bo Zhang*

1Department of Ultrasound,2Department of General Surgery,3Department of Pathology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

?

Pathology Verified Concomitant Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma in the Sonographically Suspected Thyroid Lymphoma: A Case Report△

Qiong Wu1?, Yu-xin Jiang1?, Jun-chao Guo2, Yu Xiao3, Xiao Yang1, Rui-na Zhao1, Xing-jian Lai1, Shen-ling Zhu1, Xiao-yan Zhang1, and Bo Zhang1*

1Department of Ultrasound,2Department of General Surgery,3Department of Pathology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

ultrasonography; primary thyroid lymphoma; papillary thyroid carcinoma; coexistence; diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Chin Med Sci J 2016; 31(1):54-58

PAPILLARY thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is the most common thyroid cancer and consists of nearly 80% of all cases of thyroid cancer.1It is associated with the lowest level of malignancy and an excellent prognosis. Primary thyroid lymphoma (PTL) is a lymphomatous process which develops in the thyroid without involvement of primary lymphoid organs or distant metastases at diagnosis.2It is a rare malignancy that accounts for 1%-5% of all thyroid malignancies and less than 2% of all extranodal lymphomas. The incidence of PTL is one or two cases per million.2,3It occurs frequently in elder woman, with a peak incidence in the sixth decade of life.2,4,5Common clinical feature of PTL is rapidly growing mass in the neck. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common histological subtype of PTL, comprising up to 70% of cases, followed by mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, comprising 10% to 23% of PTL.4-6Other subtypes such as follicular lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and Burkitt’s lymphoma are comparatively rare. To our knowledge, the co-occurrence of PTL and PTC is extremely rare, and only 12 cases have been previously reported.7-15We report a sonographically suspected PTL case who was pathologically diagnosed with PTL and PTC.

CASE DESCRIPTION

In December 2009, a 53-year-old woman was admitted to local hospital with a palpable mass in the neck. Ultrasonography (US) indicated diffuse lesions of the thyroid gland, but the thyroid hormone determination showed a euthyroidism. She was clinically suspicious of thyroiditis. The patient was, consequently, treated withoral medications of traditional Chinese medicine and levothyroxine sodium, and skin patches of herbal medicine. However, these treatments were ineffective and a gradual enlargement of the thyroid gland was confirmed by the follow-up of ultrasound over the period of two years. In April 2012, thyroid US revealed multiple goiters in both lobes of the heterogeneous gland, which supported Hashimoto’s throiditis (HT) but could not exclude the possibility of thyroid lymphoma. The patient was subsequently examined by fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of the left lobe. The cytology also concurred with the suspicion of HT. A gradual enlargement of the thyroid gland was evident in the subsequent follow-up of ultrasound.

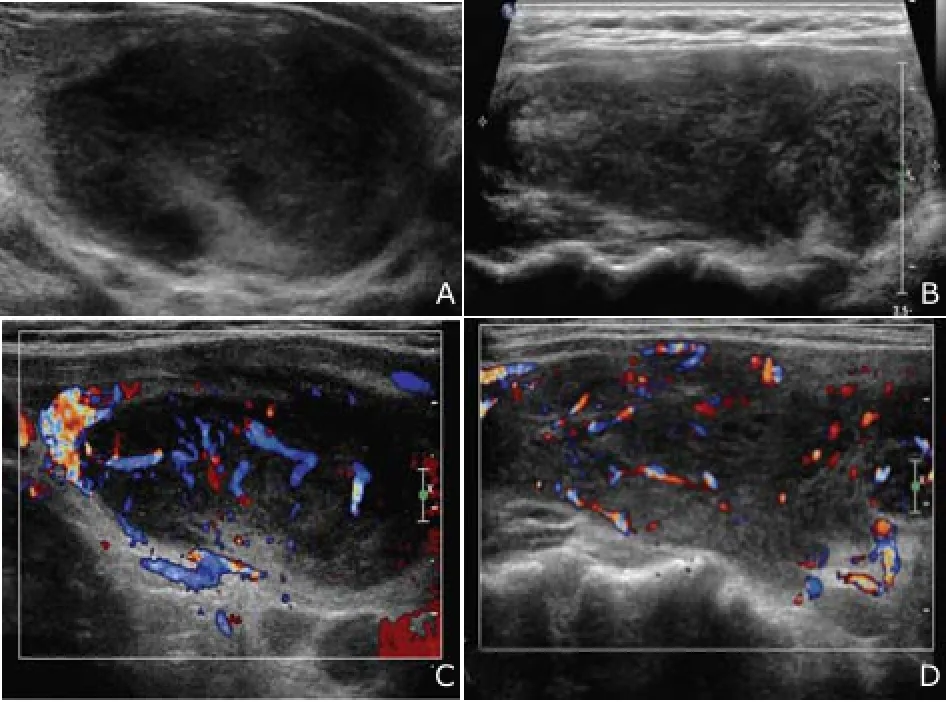

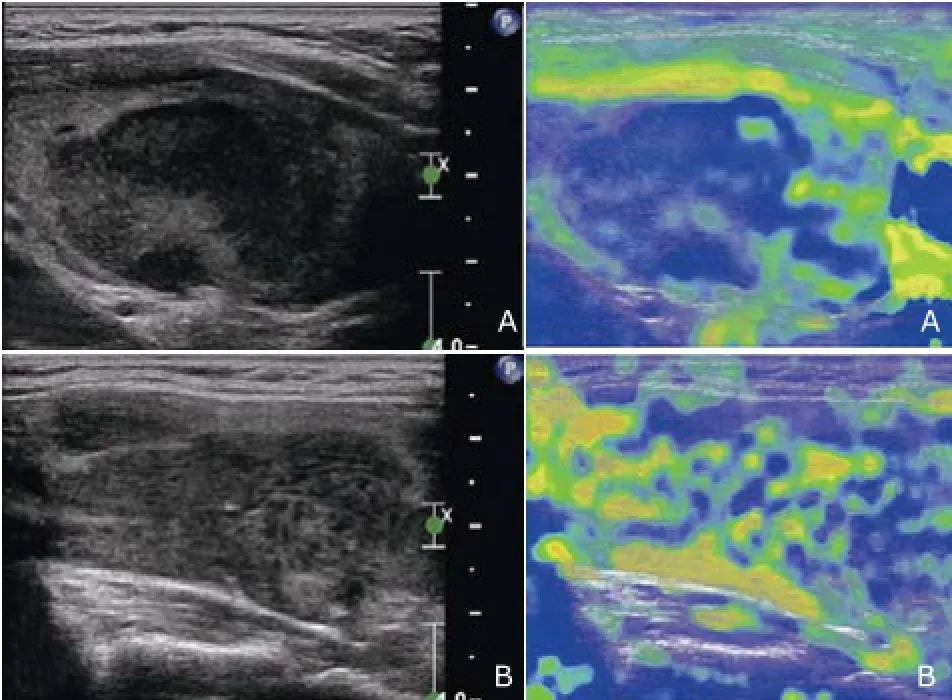

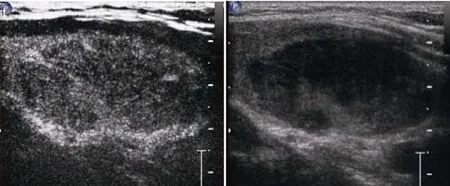

Nevertheless, the patient noticed a progressive enlargement of the neck mass from July 2013 and was referred to our hospital in December 2013. Physical examination revealed visible bilateral goiters that were painless and of poor mobility but no swelling lymph nodes on palpation. Thyroid function test was still normal. US revealed diffuse enlargement of the thyroid gland (measuring 8.3 cm×2.6 cm×2.3 cm of the right lobe, 6.6 cm×2.9 cm×2.1 cm of the left lobe and 1.3 cm of isthmus thickness) with heterogeneous background parenchyma. The imaging showed a defined hypoechoic nodule measuring 4.3 cm×2.2 cm in the left lobe. Several diffuse hypoechoic areas with interspersed linear echogenic strands can be seen in the right lobe and the isthmus. The large area in the right lobe measured 6.0 cm×2.2 cm. Color Doppler showed abundance of blood flow in the hypoechoic nodule and in the surrounding area (Fig. 1). Real time elastosonography displayed most of the nodule was blue and a small part of it was green, which indicated the echoic nodule’s hardness was uneven. Most was hard and a small part was relatively soft. While the hypoechoic area was composed of blue, green, and yellow, which reflected the hardness of the area was moderate (Fig. 2). Contrastenhanced US indicated a rapid flushing of bubble into the nodule at the arterial phase and formed a ring-enhancement at the border of the nodule at the wash-out phase (Fig. 3). FNAB of the nodule in the left lobe was performed and cytology combined with immunohistochemistry demonstrated a consistency with HT but without an exclusion of lymphoma.

Figure 1. Conventional ultrasonography shows heterogeneous hypoechoic nodule in the left lobe (A) and hypoechoic area in the right lobe with interspersed linear echogenic strands (B). Color Doppler shows abundance of blood flow in the hypoechoic nodule in the left lobe (C) and abundance of blood flow in the hypoechoic area in the right lobe (D).

Figure 2. Real time elastosonography shows most of the nodule in the left lobe is blue and a small part of it is green (A). Elasto- sonography shows the hypoechoic area in the right lobe is composed of blue, green, and yellow (B).

Figure 3. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography shows a ringenhancement at the border of the nodule at the washout phase.

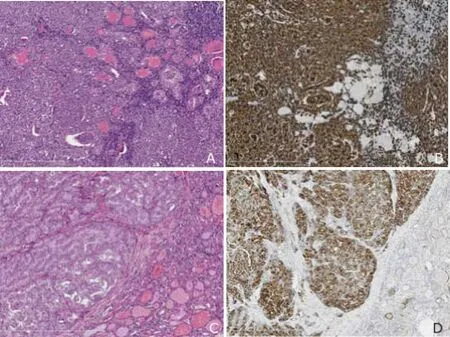

To make the exact diagnosis, the patient underwent partial thyroidectomy. Left lobe of the thyroid was excised and the intraoperative frozen section still revealed the possibility of lymphoma. Histological pathology combined with immunohistochemistry (CK19+/TTF-1+/Thy+/Bcl-6+/ CD10-/CD20+/CD3+/CD30 (Ki-1)+-/p53+B cells with Ki67 of 40%) eventually confirmed the diagnosis of DLBCL ofnon-germinal B cell-like subtype. Moreover, a local PTC was detected incidentally and no metastatic or infiltrated lymph nodes were found (Fig. 4). Bone marrow examination and fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET)/computed tomography (CT) were subsequently performed in order to determine the stage of lymphoma. Considering that there was no evidence of lymph node enlargement in the neck, mediastinum, or abdomen and bone marrow biopsy was normal, DLBCL was considered to be confined to the thyroid gland, corresponding to stage IE according to Ann Arbor classification.

Postoperatively, after she received six cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisolone) chemotherapy, US showed that the residual thyroid gland became normal and18F-FDG uptake of the residual thyroid gland was decreased in PET/CT. However, a new uptake of18F-FDG by lymph node in the intramuscular space close to hip joint emerged. The seventh and eighth cycles of R-CHOP were instead by only rituximab because the patient refused to receive the R-CHOP chemotherapy. The patient continues to be monitored without new symptoms by now.

Figure 4. Pathological results of the nodule in the left lobe.A. Histological pathology is non-Hodgkin lymphoma of thyroid (diffuse large B-cell type). HE staining shows tumor cells surrounding lymphoid follicles with a diffuse pattern. ×100B. Immunohistochemical staining shows lymphoma is strong immunoreactive for CD20, but the normal thyroid glands negative for CD20. ×100C. HE staining demonstrates that the tumor cells of follicular variant of papillary carcinoma in the upper left area show monoclonal large ground glass nulei, compared with non-neoplastic thyroid glands in the lower right area. ×100D. Immunohistochemical staining shows that papillary carcinoma is strong positive for CK19, but the normal thyroid glands shows focally weak positive immunostaining for CK19. ×200

DISCUSSION

For the diagnosis of PTL, radionuclide scanning, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are not routinely used because they are nonspecific. CT and MRI can be used to assess the involvement of surrounding structures.18FDG-PET can be useful in staging and assessing response to treatment in PTL.16While US is the preferred imaging method for thyroid disease, similarly for PTL.

The ultrasonographic imaging of PTL is diverse. Ota et al17classified thyroid lymphoma into three patterns: nodular, diffuse, or mixed. When presenting as the nodular type, the typical appearance can be a homogenous hypoechoic goiter without calcification, necrosis, and cystic degeneration18and the boundary between the tumor and the surrounding tissue is very clear. When diffuse lymphoma is identified, it appears as a heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion with the presence of septa-like structures. The boundary of the lesion was not clear.19Our case may be classified as the mixed type. The tumor in the left lobe is not so homogenous, which was discordant with the well-known appearance of lymphoma. The feature of the diffuse hypoechoic area is in accordance with that demonstrated above. Ota et al17also found that an enhanced echo behind the lesion was specific for thyroid lymphoma. This sign can be observed in our case too. Although the nodular type can be confused with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, it is relatively easier to diagnose the nodular type and mixed type for radiologists in ultrasound. However, gaining a correct diagnosis of the diffuse type is difficult because similar characters can also be found in severe HT imaging. In this situation, US will be restricted and other examinations may be helpful. Encouragingly, we identified the nodule in the left lobe which leads to the following proper procedure but unfortunately, we failed to identify the lesion of PTC. The main reason is that the lesion which is tiny hides in the hypoechoic lymphoma nodule and lacks typical features such as microcacification.

A history of long-standing HT is the major risk factor for PTL. Previous reports indicate that the likelihood of developing PTL is 67 times greater in patients with HT, relative to the general population.20It has been postulated that the intrathyroidal lymphoid tissue in HT resembles MALT and may evolve into non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Chronic stimulation by antigens may be associated with the development.21However, the exact mechanism of thismalignant transformation remains obscure. Interestingly, our patient had been diagnosed as HT until the final surgical pathology confirmed PTL. Whether the patient once suffered from HT is unclear. We speculate that there may be two possibilities. The first is that PTL disease existed in the thyroid at the beginning but it has been misdiagnosed as HT. The normal thyroid function may support this view. Although she has accepted FNAB twice, unfortunately, FNAB has a low reported accuracy for the diagnosis of PTL.22This is largely due to the histopathological similarities between PTL and HT. The second is that HT once existed in the thyroid and evolved into PTL eventually. It is reported that 0.6% with HT will go on to develop PTL.23

The concomitance of PTL and PTC is extremely rare. In all reported cases, the two lesions occurred in different lobes, which is different from our case. The association between PTL and PTC is unknown. However, both are reported in conjunction with HT. PTL and PTC are more likely to occur on the background of HT. Therefore, US is essential for HT patients to assess the disease progression and identify new lesions at a follow-up audit. If any suspicious sign of PTL or PTC appears on the ultrasonic imaging, further diagnostic procedures may be suggested by radiologists in ultrasound.

FNAB with ultrasound guidance is the initial technique for pathological assessment of a thyroid lesion. However, the cytological diagnosis of thyroid lymphoma is still controversial. Multiple small retrospective studies24-28have demonstrated that the use of flow cytometry, immunocytochemistry, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has improved the accuracy of cytology in diagnosing lymphoma. Furthermore, it is suggested that the diagnosis of DLBCL is easier because of the presence of large monotonous atypical cells. In comparison, the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma is harder because of the presence of large numbers of heterogeneous cells and the associated presence of HT.29Unfortunately, FNAB failed to get the correct diagnosis in our case, but the proposal of a possibility of PTL leads to surgical open biopsy, which is beneficial for the patient because an incidental PTC lesion was removed. Although FNAB is simple and convenient, sometimes it is not adequate for identifying the exact subtype. Core biopsy and surgical open biopsy may still be required for diagnosing and subtyping so that treatment can be tailored to individual patients.

As PTL and PTC occurs simultaneously, the treatment should be individualized, aimed at whichever tumor is more aggressive. For PTC, surgical resection is the common therapy. While the optimal therapy strategy of PTL remains controversial and depends on staging and different subtypes. The gold standard for management of DLBCL is multimodal because of the typically aggressive clinical course and uses of a combination of the monoclonal antibody rituximab, chemotherapy (a combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone [CHOP]), and radiotherapy.29Surgery is not recommended and should be limited to relieve from acute airway obstruction. Our patient received unilateral lobe resection and R-CHOP chemotherapy, which seems to be an appropriate choice.

In conclusion, the concomitance of PTL and PTC is rather rare. Although the pre-operative diagnosis is difficult, US plays an important role and can provide useful information to clinicians so that better strategy can be adopted for diagnosis and treatment. Patients with HT should be monitored carefully, especially for those with recent enlarging masses and newly presented symptoms located in the paratracheal region of the neck. Radiologists in ultrasound should pay close attention to any suspicious signs in the sonograms. The possibility of PTL, PTC or a combination of both should be considered.

REFERENCES

1. Repplinger D, Bargren A, Zhang YW, et al. Is Hashimoto's thyroiditis a risk factor for papillary thyroid cancer? J Surg Res 2008; 150:49-52.

2. Green LD, Mack L, Pasieka JL. Anaplastic thyroid cancer and primary thyroid lymphoma: a review of these rare thyroid malignancies. J Surg Oncol 2006; 94:725-36.

3. Ansell SM, Grant CS, Habermann TM. Primary thyroid lymphoma. Semin Oncol 1999; 26:316-23.

4. Thieblemont C, Mayer A, Dumontet C, et al. Primary thyroid lymphoma is a heterogeneous disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:105-11.

5. Graff-Baker A, Roman SA, Thomas DC, et al. Prognosis of primary thyroid lymphoma: demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1408 cases. Surgery 2009; 146:1105-15.

6. Tabaqchali MA, Hanson JM, Johnson SJ, et al. Thyroid aspiration cytology in Newcastle: a six year cytology/ histology correlation study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2000; 82:149-55.

7. Xie S, Liu W, Xiang Y, et al. Primary thyroid diffuse large B-cell lymphoma coexistent with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a case report. Head Neck 2014; 37:E109-14.

8. Jayaprakash K, Kishanprasad H, Hegde P, et al. Hashimotos thyroiditis with coexistent papillary carcinoma and Non-hodgkin lymphoma-thyroid. Ann Med Health Sci Res2014; 4:268-70.

9. Nam YJ, Kim BH, Lee SK, et al. Co-occurrence of papillary thyroid carcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in a patient with long-standing hashimoto thyroiditis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2013; 28:341-5.

10. Tarui T, Ishikawa N, Kadoya S, et al. Co-occurrence of papillary thyroid cancer and MALT lymphoma of the thyroid with severe airway obstruction: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014; 5: 594-7.

11. Vassilatou E, Economopoulos T, Tzanela M, et al. Coexistence of differentiated thyroid carcinoma with primary thyroid lymphoma in a background of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:e709-12.

12. Cheng V, Brainard J, Nasr C. Co-occurrence of papillary thyroid carcinoma and primary lymphoma of the thyroid in a patient with long-standing Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Thyroid 2012; 22:647-50.

13. Melo GM, Sguilar DA, Petiti CM, et al. Concomitant thyroid Malt lymphoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 2010; 54:425-8.

14. Cakir M, Celik E, Tuncer FB, et al. A rare coexistence of thyroid lymphoma with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Ann Afr Med 2013;12:188-90.

15. Macak J, Rydlova M, Horacek J, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of papillary carcinoma, oncocytic carcinoma and malignant lymphoma of the thyroid gland in a female patient with Hashimoto's disease. Cesk Patol 2001; 37:18-22.

16. Treglia G, Del Ciello A, Di Franco D. Recurrent lymphoma in the thyroid gland detected by fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT. Endocrine 2013; 43:242-3.

17. Ota H, Ito Y, Matsuzuka F, et al. Usefulness of ultrasonography for diagnosis of malignant lymphoma of the thyroid. Thyroid 2006; 16:983-7.

18. Aiken AH. Imaging of thyroid cancer. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2012; 33:138-49.

19. Nam M, Shin JH, Han BK, et al. Thyroid lymphoma: correlation of radiologic and pathologic features. J Ultrasound Med 2012; 31:589-94.

20. Holm LE, Blomgren H, Lowhagen T. Cancer risks in patients with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. NEJM 1985; 312:601-4.

21. Rossi D. Thyroid lymphoma: beyond antigen stimulation. Leuk Res 2009; 33:607-9.

22. Hwang YC, Kim TY, Kim WB, et al. Clinical characteristics of primary thyroid lymphoma in Koreans. Endocr J 2009; 56:399-405.

23. Watanabe N, Noh JY, Narimatsu H, et al. Clinicopathological features of 171 cases of primary thyroid lymphoma: a long-term study involving 24 553 patients with Hashimoto's disease. Br J Haematol 2011; 153: 236-43.

24. Matsuzuka F, Miyauchi A, Katayama S, et al. Clinical aspects of primary thyroid lymphoma: diagnosis and treatment based on our experience of 119 cases. Thyroid 1993; 3:93-9.

25. Sangalli G, Serio G, Zampatti C, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of primary lymphoma of the thyroid: a report of 17 cases. Cytopathology 2001; 12:257-63.

26. Cha C, Chen H, Westra WH, et al. Primary thyroid lymphoma: can the diagnosis be made solely by fine-needle aspiration? Ann Surg Oncol 2002; 9:298-302.

27. Morgen EK, Geddie W, Boerner S, et al. The role of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of thyroid lymphoma: a retrospective study of nine cases and review of published series. J Clin Pathol 2010; 63:129-33.

28. Dustin SM, Jo VY, Hanley KZ, et al. High sensitivity and positive predictive value of fine-needle aspiration for uncommon thyroid malignancies. Diagn Cytopathol 2012; 40:416-21.

29. Walsh S, Lowery AJ, Evoy D, et al. Thyroid lymphoma: recent advances in diagnosis and optimal management strategies. Oncologist 2013; 18:994-1003.

for publication September 20, 2015.

?These authors contributed equally to this work.

*Corresponding author Tel: 86-10-69159318, E-mail: zora19702006@ 163.com

△Supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81541131)

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2016年1期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2016年1期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Resulting from a Troponin I Type 3 Mutation in a Chinese Family

- Association Between Geranylgeranyl Pyrophosphate Synthase Gene Polymorphisms and Bone Phenotypes and Response to Alendronate Treatment in Chinese Osteoporotic Women△

- Positive Rate of Different Hepatitis B Virus Serological Markers in Peking Union Medical College Hospital, a General Tertiary Hospital in Beijing△

- Establish Albumin-creatinine Ratio Reference Value of Adults in the Rural Area of Hebei Province△

- Respiratory and Cardiac Characteristics of ICU Patients Aged 90 Years and Older: A Report of 12 Cases

- Percutaneous Removal of Benign Breast Lesions with an Ultrasound-guided Vacuum-assisted System: Influence Factors in the Hematoma Formation△