The use of outcome feedback by emergency medicine physicians: Results of a physician survey

Rakesh Gupta, Isaac Siemens, Sam Campbell

1 Division of Emergency Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

2 Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

3 Department of Emergency Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

KEY WORDS: Return visit reports; Emergency medicine; Outcome feedback; Emergency department information system

INTRODUCTION

Outcome feedback is the process of determining a patient’s clinical outcome after their evaluation and treatment.[1]Such feedback allows physicians to calibrate their decision making over time based on the positive and negative outcomes that result from their management of patients.[2]In medical practice more broadly, most physicians obtain feedback through patient follow up.However, the discontinuous nature of emergency medicine precludes emergency physicians (EPs) from easily obtaining outcome feedback regarding the patients they see. Additional mechanisms, informal or formal, are often needed for EPs to receive information about patient outcomes.

Current literature shows that there is a demand for outcome feedback among EPs.[3]One review found that the most commonly used mechanisms of EP outcome feedback were telephone calls to discharged patients,automatic routing of admission and discharge summaries,and case conferences.[1]However, there is a scarcity of information in the literature about which systems of outcome feedback have been implemented and what their impact is on clinical practice.

In this study, we examine a mechanism of feedback called the return visit report (RVR) which is currently being used by EPs at three emergency departments(EDs) in Nova Scotia, Canada. Each EP receives a RVR comprised of a list of patients they discharged who returned to any nearby ED within 72 hours.The list includes the EPs final diagnosis at the initial patient encounter and at the return visit, as well as identifying information that allows the EP to recall the case and access the patient’s electronic chart. RVRs are automatically generated by the emergency department information system (EDIS) and distributed to each EP either monthly or every three months, depending on the institution.

We evaluate the utility of RVRs by surveying EPs about how they use this and other forms of outcome feedback.In doing so, we aim to advance the available knowledge in this field and encourage further examination of institutional outcome feedback mechanisms.

METHODS

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of EPs from three hospitals in Nova Scotia (QEII Halifax Infirmary,Halifax; Dartmouth General Hospital, Dartmouth;Cobequid Community Health Centre, Lower Sackville).The sites comprise one tertiary care center (Halifax) and two community hospitals (Dartmouth and Cobequid).We attempted to enroll all 81 EPs who worked at any of these sites at the time of the study. There were no exclusion criteria. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Dalhousie University.

Survey content and administration

The survey consisted of fourteen questions in total(Table 1). Questions 1-6 were demographic questions(Table 2). Questions 7-11 asked about RVR use using Likert scale responses (Table 3) but with options for free text answers as well. Questions 12-14 were questions with combination free text and select from list answers.

The survey was web-based and was hosted by Opinio. A link to the survey was distributed to EPs via institutional e-mail. Two additional e-mails containing the survey link were distributed at four and eight weeks after the original e-mail to EPs who had not yet responded. No identifying information was recorded during the survey. Consent was implied by survey completion.

Data analysis

A proportional odds logistic regression analysis was performed to determine if any demographic data corresponded with the responses of Likert scale questions.

RESULTS

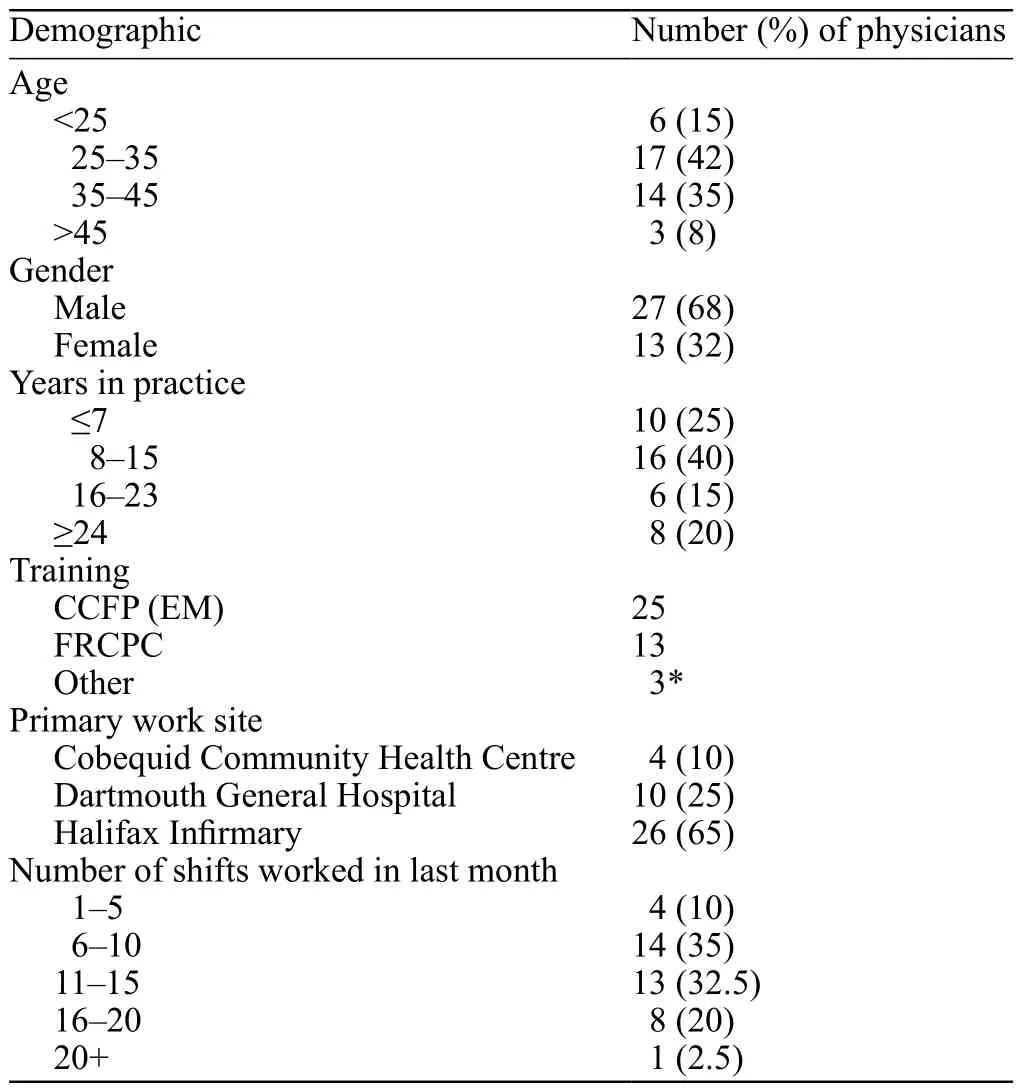

Eighty one EPs from three EDs receiving RVRswere identified as eligible for the survey. Of these, 40(49%) completed the survey. The demographic data in questions 1-6 were mandatory and so all 40 respondents completed the demographics section. Only 30 out of the 40 respondents completed all questions. Respondent demographics are presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Overview of survey questions

Responses to Likert scale questions (questions 7-11)are presented in Table 3. When asked about the value of RVRs, the majority of participants “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that RVRs are “valuable to their practice of medicine” (24/30, 80%) and more broadly that information about patient outcomes is “valuable to their practice of medicine” (26/30, 87%). Many physicians“agreed” or “strongly agreed” that information about return visits “alters their practice in future patient encounters” (17/30, 57%).

Table 2. Responses to demographic information (Survey questions 1-6)

Table 4. Alternate outcome feedback mechanisms (Survey question 13)

When asked how they utilized their RVRs, most participants reported “usually” or “always” reviewing their RVRs (25/30, 83%) and examining the diagnoses of patients listed in their RVRs (26/30, 87%). Some respondents “usually” or “always” “sought additional information about the outcomes of patients listed in their RVRs” (12/30, 40%).

When asked about alternate mechanisms of obtaining outcome feedback, the majority of participants reported speaking with other EPs (25/30, 83%) and reviewing discharge summaries of admitted patients (26/30, 87%).An overview of the results of question 13 which addresses alternate means of feedback can be seen in Table 4.

Question 12 asked about how much time physicians spent reviewing their RVRs and answers ranged from 2 minutes to 1 hour. Question 14, as well as the free text answer options from questions 7-11, generated qualitative data about RVRs described below. A formal qualitative analysis was not performed.

Proportional odds logistic regression analysis showed no correlation between demographic data and Likert scale responses, including academic versus community locations. There was no correlation between demographic data and those who didn’t complete all questions.

DISCUSSION

The data collected in our survey indicate that the majority of physicians using RVRs find this form ofoutcome feedback to be valuable to their practice. The majority of physicians are reviewing the data in their reports frequently and are using that data to calibrate their future practice. This is in keeping with previous research showing that EPs are keen to have more mechanisms of outcome feedback available to them.[3]

Table 3. Likert scale responses (Survey questions 7-11)

A theoretical framework for evaluating outcome feedback mechanisms has been proposed by Croskerry and Lavoie.[4]They outline six parameters whereby the effectiveness of feedback can be evaluated: observation interval, reporting delay, reporting accuracy, report relevance, differential weighting, and evaluative contamination. This framework allows us to apply these measures to the specific form of outcome feedback that we describe in this study.

Observational interval refers to the period of time between the patient encounter and measurement used for feedback.[4]Reporting delay refers to the period of time between observation of the patient outcome and the report to the clinician.[4]These two intervals must be balanced in order to allow enough time for an illness to take its course so accurate outcome feedback can be provided, but also to provide feedback while the EP still recalls the case details. Our system of RVRs provides data compiled over one to three months, so up to three months may have elapsed between a patient encounter and receiving feedback at one institution.

Reporting accuracy refers to the degree to which feedback reflects the actual patient outcome.[4]Our system lists the final diagnosis assigned by the EP at the initial patient encounter and at the return visit. These listed diagnoses are not perfect and are subject to a number of possible biases which limit their accuracy. One important limitation is that a patient may have multiple relevant issues but typically only a single diagnosis is listed.

Report relevance refers to the ability of the feedback to influence therapeutic interventions performed by the EP.[4]Differential weighting refers to the ability of an outcome feedback mechanism to provide information on each part of the decision making process.[4]Attention to both of these criteria should yield outcome feedback that is both concise and thorough. Only cases and information which a physician can use to calibrate their decision making should be included in the feedback report. This ensures the information is of high value and reduces the amount of time physicians have to spend obtaining outcome feedback from additional sources.

The report relevance and differential weighting of RVRs are limited by the capabilities of the EDIS which automatically generates these reports. RVRs include any patient who returns to the ED within 72 hours, even those that are asked to return, for example, to have a wound checked or to receive intravenous antibiotics.These are scheduled return visits which ideally should not be included the RVR, and this point was echoed in the short answer responses to our survey.

Additionally, the outcome feedback provided by RVRs is limited to final ED diagnoses. We believe that learning about diagnoses of discharged patients returning to the ED provides EPs with valuable information that allows them to identify potential missed diagnoses and calibrate their practice accordingly, which is reflected in our survey results. Survey respondents also indicated that they seek additional information relevant to calibrating their decision making, such as diagnostic imaging results and discharge diagnoses for admitted patients. Including this information in the report itself, or ready links to this information, would improve the report accuracy,report relevance, and differential weighting of RVRs. As hospital system electronic medical records become more robust, we expect this function to become more feasible.

Evaluative contamination refers to the potential biases of the evaluator who is providing feedback, including recall bias or knowingly factitious feedback. As RVRs are automatically generated from raw EDIS data, evaluative contamination is greatly limited. However, there are biases inherent in the development of this system, as with any system. The data that is collected is chosen by supervising physicians and so the parameters they choose are subjective and include the potential for bias.

Given the above discussion regarding optimizing feedback, we have several suggestions for next steps regarding the RVRs from this study and feedback more broadly. We suggest that RVRs be delivered on a monthly rather than quarterly basis to optimize the observational interval and reporting delay. We also recommend implementing a method for users to exclude patients who return to care for scheduled follow up as this contaminates the data that physicians are receiving.Finally, we suggest expanding the information on the reports to include key calibration data such as disposition upon return visit and imaging results.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations to our survey data. The response rate of 49% allows for the possibility of significant nonresponse bias, and it is possible that the group of physicians who are not responding to e-mail surveys are less likely to be utilizing e-mailed outcome feedback reports. The survey could only be distributed to EPs who are receiving RVRs in a relatively small geographical location, which may limit the external validity of the results. We also acknowledge that while 40 physicians completed the mandatory demographic questions, 10 physicians of these did not complete the remaining survey questions. This may be because they had not yet engaged in the use of RVRs.

The validity of the survey results may also be limited by social desirability bias. If using outcome feedback is regarded as a positive trait, physicians may overestimate how frequently they utilize RVRs or other outcome feedback mechanisms. This bias is somewhat mitigated by the anonymity of the survey. Self-reporting of the impact of RVRs on future practice is subjective and may be affected by recall bias, and the impact on patient outcomes remains uncertain.

CONCLUSION

Based on our survey results, RVRs are a valuable form of feedback for EPs. The majority of surveyed physicians report consistently using RVRs to calibrate their practice. Respondents report seeking other forms of outcome feedback including speaking with other physicians and reviewing discharge summaries. None of the demographic data we collected correlated with opinions regarding RVRs. By applying an existing framework for evaluating feedback mechanisms, we have identified observational interval, report relevance, and differential weighting as primary areas for improvement in RVRs, but acknowledge that these are limited by the technical capabilities of the EDIS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the valuable input received from Dr. Pat Croskerry.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:The study was approved by the institutional review board at Dalhousie University.

Conflicts of interest:Authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest related to this submission.

Contributors:RG proposed the study and wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

World journal of emergency medicine2019年1期

World journal of emergency medicine2019年1期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Instructions for Authors

- Elderly male with blurry vision

- Hemodynamic improvement using methylene blue after calcium channel blocker overdose

- Intussusception in an infant with two non-diagnostic abdominal ultrasound studies

- Assessment of clinical dehydration using point of care ultrasound for pediatric patients in rural Panama

- Prehospital response to respiratory distress by the public ambulance system in a Ukrainian city