Treatment of eosinophlic esophagitis with swallowed topical corticosteroids

Simon Nennstiel, Christoph Schlag

Abstract Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an emerging chronic local immune-mediated disease of the esophagus. Beside proton pump inhibitors and food-restrictiondiets swallowed topical corticosteroids (STC) can be offered as a first line therapy according to current guidelines. This review describes the background and practical management of STCs in EoE. So far, mainly asthma inhalers containing either budesonide or fluticasone have been administered to the esophagus by swallowing these medications “off label”. Recently esophagus-targeted formulations of topical steroids have been developed showing clinicopathological response rates up to 85% - an orodispersible tablet of budesonide has been approved as the first “in label” medication for EoE in Europe in June 2018. Whereas it was shown that disease remission induction of EoE by STCs is highly effective, there is still a lack of data regarding long-term and maintenance therapy. However, current studies on STC maintenance therapy add some movement into the game.

Key Words: Eosinophilic esophagitis; Swallowed topical corticosteroids; Esophagustargeted formulations of topical steroids; Fluticasone; Budesonide; Budesonide orodispersible tablet; Budesonide oral suspension

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is defined as a chronic local immune-mediated esophageal disease, characterized clinically by esophageal dysfunction and histopathologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation[1-3]. Since EoE was first described as a new disease entity in the early 1990s[4,5], its incidence and prevalence have remarkably increased with a pooled prevalence of 34.4 cases per 100000 inhabitants (adults 42.2/100000; children 34/100000) and a pooled incidence of 7.7/100000 patient-years for adults and 6.6/100000 patient-years for children[6]. Although, EoE right now still has to be considered a rare disease, the increasing incidence and prevalence make it more likely to encounter a patient with EoE in everyday practice.

Adult EoE-patients typically suffer from dysphagia, bolus impaction and retrosternal pain whereas in children predominant symptoms are abdominal pain, vomiting and failure to thrive. Upper endoscopy with esophageal biopsies is always required to diagnose EoE. Typical endoscopic findings are mucosal edema, white exudates and furrows as signs of acute inflammation as well as rings and strictures as signs of fibrostenotic remodelling of the esophagus. However, approximately 10% of adult patients and up to 32% of children will have a normal appearing esophagus[7]- therefore at least 6 biopsies from different levels of the esophagus (typically proximal and distal) have to be taken and the proof of a minimum of 15 eosinophils per high power field (hpf) in at least one biopsy is mandatory for EoE diagnosis. Additional biopsies of the stomach and duodenum should be taken when EoE is newly diagnosed to exclude other causes of esophageal eosinophilia, such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis[2,3].

EoE patients predominantly are white young males with concomitant atopic conditions[8]and IgE related food allergies. In these genetically susceptible patients, the esophageal exposure to patient-specific food-antigens, probably promoted by an increased mucosal permeability trigger a T-helper type 2 (Th2) cell response leading to the production of key-cytokines including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. These cytokines promote further eosinophilic leukocyte activation, recruitment and inflammation of the esophagus mainly driven by eotaxin-3. Esophageal eosinophilia also promotes development of tissue fibrosis by transforming growth factor beta and periostin which enhances remodelling, fibrosis and stricture formations[9,10]. Hence, natural history of EoE has to be understood as a progression from inflammation to fibrosis[11-14]. Patients with a fibrostenotic phenotype more often report dysphagia and food impaction, have a longer duration of dysphagia symptoms, and thus, a longer disease duration and are older than patients with the inflammatory phenotype[13]. EoE has a substantial negative impact on deglutition and on the patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL)[15], especially if not treated sufficiently. Moreover, once advanced fibrosis and stricture formation are existent, medical or dietary treatment are not able to fully improve dysphagia and the quality of life – in these cases endoscopic dilatation-therapy with the possible risk of complications has to be added[16].

TREATMENT OBJECTIVES IN EOE

Current guidelines lack explicit disease management goals, considering the deficient available data. The optimal treatment objectives have yet to be defined. So far, the major goals of (short-term, remission-induction) EoE-therapy are improvement of histologic, symptomatic, and endoscopic outcomes. Other outcome measures include quality of life, occurrence of complications like food impaction, biomarkers and especially in children normal growth/thrive[13]. The main histopathological measure normally looked at is the (peak) eosinophil count (eos/hpf) and in studies the therapeutic objective is normally defined as decrease of this peak eosinophil count to at least < 15 eos/hpf (variation between studies). Also other features such as basal zone hyperplasia, eosinophil abscesses, eosinophil surface layering, dilated intercellular spaces, surface epithelial alteration, dyskeratotic epithelial cells and lamina propria fibrosis can be observed on which a standardized histological measure has been proposed by Collinset al[17]Concerning the symptoms of EoE, the therapeutic goal is an improvement, or stricter a cessation of symptoms after therapy. Different validated symptom measures are available, for example the Eosinophilic Esophagitis Activity Index or the Dysphagia Symptoms Questionnaire (DSQ) for adults and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory EoE for children. Endoscopic-macroscopic signs of EoE can be best objectively assessed with the Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS - acronym for exudates, rings, edema, furrows, and strictures), which allows an endoscopic assessment of EoE disease activity – therapeutic goal is at least a decreased score to less than baseline or better a normalization of esophageal changes[18-23].

As already explained, EoE progresses from inflammation to fibrosis, so long-term treatment goal has to be maintenance of disease remission. Current guidelines do not include recommendations in terms of long-term management strategies (e.g., intermittent or continuous therapy) and the exact extent of disease remission with regard to prognosis or disease progression still needs to be defined[24]. While there is quite good correlation between endoscopic signs (EREFS-score) and histologic improvement[25], a problems remains only modest correlation between symptoms and endoscopic/macroscopic as well as histologic disease activity[26,27]. Therefore, the efficacy of any first line anti-inflammatory therapy should be checked by a follow-up endoscopy after a 6- to 12-wk initial course[3].

From patients’ perspective, symptoms and quality of life improvement are the most important short- and long-term therapy goals in EoE[28]. In addition, through patient information about the connection of preventing symptom recurrence by inflammationcontrol, patients can probably be motivated to better long-term therapy adherence[28].

SHORT-TERM TREATMENT: INDUCTION OF REMISSION

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), food-restriction-diets and swallowed topical corticosteroids (STCs) can be offered as first line anti-inflammatory therapy in EoEpatients[3].

The mechanism of action of glucocorticoids in EoE is mainly based on the reduction of inflammatory cells and fibrosis: in short term treatment with STC results in a significant decrease of esophageal eosinophils, mast cells, T-cells and proinflammatory cytokines as well as restoration of epithelial barrier function and reduction of tissue remodeling[29-31]. Moreover, it has been shown that the EoE IL-13–induced transcriptome (IL-13 induced pathways and genes) is largely reversible with glucocorticoid treatmentin vivo[32].

In 1998, Liacouraset al[33]was the first to describe successful treatment of EoE with STCs in children. A subsequent randomized controlled trial (RCT) in 80 children showed equal effectiveness of systemic prednisone and topical fluticasone in achieving histological and clinical improvement but systemic prednisolone was associated with more adverse events[34]. Because of these findings STCs should generally be preferred. Systemic steroids may only be considered as an exception in patients who require rapid improvement of symptoms (e.g., children with severe symptoms, malnutrition or feeding intolerance)[2].

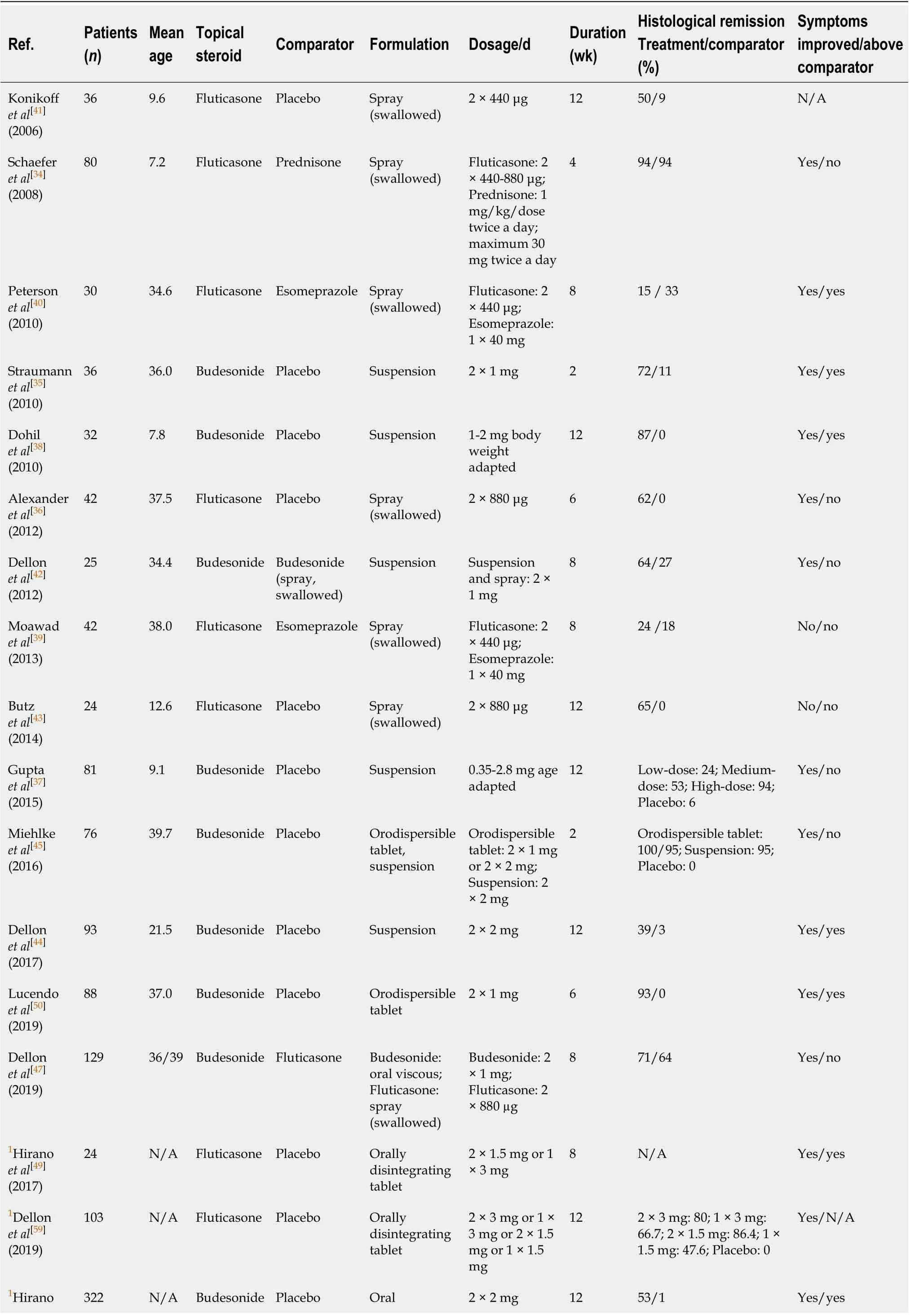

The effectiveness of STC-therapy in EoE has been shown in several studies in both children and adults. The most thoroughly evaluated topical corticosteroids are budesonide and fluticasone. Until today, seventeen randomized trials[34-50]comprising nine placebo-controlled studies have been published (Table 1). Parts of these data have been summarized in different meta-analyses[51-56]. These studies considerably vary regarding inclusion criteria, agents, daily dosages, length of treatment and end point definitions, showing histologic remission rates from 39%-100% and mainly sufficient clinical response. However, a lack of correlation between symptoms and histology has been observed in some studies. This might be explained by possible insufficient durations of therapies, by fixed fibrosis or most likely by the usage of non-validated and/or insufficient patient reported outcome metrics[57].

Fluticasone

The first experience with STCs was presented in 1998 in a paediatric case series of 11 children with EoE. Fluticasone was administered orally as spray from a metered-dose inhaler (age-adapted: 88-440 μg twice a day). After 8 wk a clinical and histological response was observed in all patients[58]. There have now been nine randomized clinical trials examining the use of swallowed fluticasone in EoE including fluticasonevsprednisone[34], fluticasonevsesomeprazole[39,40], fluticasonevsbudesonide[47]and five placebo-controlled trials: The first of these trials in which 36 children were treatedeither with Fluticasone (440 μg twice daily) or placebo for 12 wk showed a significant higher histological (67%vs27%) and clinical (50%vs9%) response in the fluticasone group[41]. In a second trial, which included 42 adult EoE patients, a histological response after six weeks was reported in 62% of the fluticasone (880 μg twice daily) and 0% of the placebo group. However, there was no significant difference regarding improvement of symptoms[36]. The third trial included 42 pediatric and adult patients who were treated with either swallowed Fluticasone from a metered-dose inhaler (880 μg twice daily) or placebo for three months. Complete histological remission was observed in 65% of patients in the fluticasone and in none in the placebo group. Again, improvement of symptoms was not significantly different between groups[43]. Recently, a phase 1/2a safety and tolerability study found very promising clinical, endoscopic and histological response rates in 22 patients who received an 8-wk treatment with an optimized fluticasone-formulation as an orally disintegrating tablet as compared to placebo[49]. The tablet is placed in the mouth and manipulated with the tongue until it is completely disintegrated – it should then be swallowed. No rinsing with water or liquids should be undertaken after administration. The subsequent phase 2b study with this formulation (FLUTE-trial) reported histologic response rates (assessed at week 12 as percent of study participants with a peak of ≤ 6 eosinophils per hpf) of 80%, 67%, 86% and 48% for the respective fluticasone-doses of 3 mg twice per day (BID), 3 mg once per day [at bedtime, hora somni (HS)], 1.5 mg BID and 1.5 mg HS. There also was significant improvement of the endoscopic disease assessment in all treatment groups, while the global EoE Symptom Score improved, however not significantly. In the placebo group, no histologic response was noted[59]. A phase 3 trial with this orally disintegrating fluticasone tablet is in preparation.

Table 1 Overview of swallowed topical corticosteroids randomized trials in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis

1Abstract data. N/A: Not applicable.

In addition, an orally administered powder formulation of fluticasone (500-1000 μg BID) was recently described as another possibility for EoE treatment. In a retrospective series of 40 patients a decrease of eosinophilic peak densities to < 15 eos/hpf was described in 75% of patients. Improvement was also demonstrated in dysphagia symptoms and endoscopic findings of furrows and exudates[60].

Budesonide

First experiences in which a budesonide aqueous solution was mixed with the sugar substitute sucralose, termed oral viscous budesonide (OVB), were reported in a small retrospective study on 20 children in 2007. Histological response was observed in 80% of patients and there was also a significant improvement of clinical symptoms and endoscopic findings, while no adverse events were recorded[61]. Until today, nine randomized trials[35,37,38,42,44,45,47,48]including seven placebo-controlled EoE studies with budesonide have been published. The first placebo-controlled study included 36 patients older than 15 years, who received budesonide-suspension (1 mg twice daily) or placebo for 15 d. A histological remission was documented in 72% of patients treated with budesonidevs11% of patients who received the placebo. Clinical symptoms and endoscopic findings also significantly improved in the budesonide group[35]. In children the first RCT, which included 24 patients also showed good results: After three months of treatment with budesonide suspension (1-2 mg/d) histological remission was achieved in 87% of patients and in none of the placebo group. Symptom and endoscopy scores also improved[38]. Another RCT examined a viscous formulation of budesonide in 71 children in three different dosage groups (0.35-4 mg/d). The primary efficacy end point was compound response to therapy (peak eosinophil counts ≤ 6/hpf) and ≥ 50% reduction in EoE symptom score. Significantly greater percentages of responders were noted in the medium-dose (52.6%) and high-dose group (47.1%) compared to the placebo group (5.6%) but not in the low dose group (11.8%). However, the significant compound responses were only accounted for by the significant histologic responses whereas symptoms substantially improved in all four groups including the placebo group[37].

Regarding the drug delivery system, an important study by Dellon and colleagues showed that budesonide 2 × 1 mg for 8 wk as a viscous suspension was superior to a nebulized preparation in inducing histologic remission (64%vs27%). The drug mucosal contact time, which was measured scintigraphically, was significantly longer in the viscous budesonide group and a significant drug exposure in the lung was seen in the nebulizer group[42]. An European phase-II-multicenter trial investigated the efficacy and safety of two different esophagus-specific targeted budesonide formulations [effervescent tablet for orodispersible use (2 × 1 mg/d and 2 × 2 mg/d) and viscous suspension (2 × 2 mg/d)] for a 14-d short-term treatment in 76 adults with a randomized, double blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled design. Both optimized budesonide-formulations induced histological remission in almost all patients (94.7%-100%) whereas no histological remission was observed in the placebo group. The improvement in total endoscopic intensity score was significantly higher in the three budesonide groups compared with placebo whereas dysphagia improved in all groups at the end of treatment; there were no serious adverse events. The effervescent tablet was preferred by 80% of patients[45]. Based on these findings a phase-III-study (EOS-1 trial) was conducted using the preferred orodispersible tablet (2 × 1 mg/d) for 6 wk in 88 adult EoE patients. The primary efficacy end point, which included histological remission (< 16 eos/mm2hpf – which corresponds to peak eosinophil count < 5 eos/hpf) and resolution of symptoms (defined as a severity of ≤ 2 points for dysphagia and a severity of ≤ 2 point for odynophagia on a not validated numeric rating scale from 0-10) was achieved after 6 wk in 57.6% of patients in the budesonide compared to no patient in the placebo group. Histological remission was achieved in 93.2%vs0% (< 0.0001), resolution of symptoms in 59.3%vs13.8% (< 0.0001) and total EREFS endoscopic score decreased by -2.6vs-0.1 points (< 0.0001). After 12 wk, remission was observed in even 85% of patients. Again, no serious adverse events were detected[50]. These promising results were confirmed by the 6-Wk Open-Label Treatment Phase of the EOS-2 trial. Here, the combined endpoint of clinichistological remission was achieved in 69.6% of patients (histological remission defined as < 16 eos/mm2hpf in 90%, clinical remission defined as improvement of dysphagia and odynophagia each ≤ 2 points on 0-10 points NRS in 75%)[62]. Lately, Greuteret al[63]suggested more stringent criteria for remission of EoE, described as “deep disease remission”. This deep disease remission was defined as deep clinical (= ‘0' points on daily numerical rating scales (0-10 points) each for dysphagia and odynophagia on each of the last 7 d) and deep endoscopic (complete absence of inflammatory signs, in particular white exudates, furrows, and edema) as well as deep histologic remission (‘0' eos/mm2hpf in all biopsies). Deep disease remission has not yet been directly linked to prognosis or disease progression[63]. A post-hoc analysis of the EOS-1 trial with these criteria showed a deep disease remission in 20% of patients (deep clinical remission: 25%; deep endoscopic remission: 58%; deep histologic remission: 90%)[64]. Since June 2018, the 1 mg orodispersible budesonide tablet (Jorveza?) has been officially approved in the Europe for EoE induction therapy.

A recent multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial in the United States included 93 active EoE patients between the ages of 11 and 40 years. Patients were randomized to receive either a new mucoadherent budesonide oral suspension (BOS) 2 mg twice daily or placebo for 12 wk. The co-primary outcomes included change in a validated dysphagia symptom score from baseline and histologic response defined as ≤ 6 eosinophils/hpf. For budesonide versus placebo change in dysphagia score was -14.3vs-7.5 (P= 0.0096), change in endoscopic severity score was -3.8vs0.4 (P< 0.0001) and histologic response rates were 39%vs3% (P< 0.0001). Aside from the validated symptoms scores a blinded 4-wk placebo-run-in period was the strength of this study[44]. Looking deeper into histopathological alterations of EoE, it was recently shown in a post-hoc analysis of the latter study, that compared with placebo, the BOS-treatment led to significant improvements not only in peak eosinophil counts, but also in a range of other histopathologic features associated with histologic severity and active disease in EoE (EoE HSS Scoring System)[17,65]. Results of a phase 3 study with this BOS were presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology – 213 patients randomized to 2 mg BOS BID over a period of 12 wk had significantly higher histologic (peak eosinophil count ≤ 6 eos/hpf) and symptomatic respond rates than 107 patients who received placebo therapy (53 %vs1% and 53%vs39 %). Patients treated with BOS also had significantly better improvement in the DSQ and in the endoscopic EREFS-Score compared to the placebo group[48].

Other STCs

Only one small case series has evaluated the use of ciclesonide, a new generation topical corticosteroid of proved benefit in the treatment of allergic diseases, which reaches high concentrations in the mucosal epithelium, in EoE: Schroederet al[66]reported its successful use in four children suffering from EoE.

In addition, a retrospective series reported oral viscous mometasone (750-1500 μg) as an effective alternative for the treatment of EoE in 34 patients with a median age of 9.4 years, achieving histologic response (< 15 peak eos/hpf) in 76% of patients, including 72% of patients previously unresponsive to other swallowed steroids[67].

LONG TERM TREATMENT

EoE is considered a chronic progressing disease and most patients suffer from rapid relapse when therapy is stopped: Greuteret al[63]analyzed 351 EoE patients retrospectively, treated with a topical steroid maintenance therapy (0.25 mg twice daily). Disease activity was assessed on an annual basis. In patients, who achieved long-lasting (≥ 6 mo) clinical, endoscopic and histological remission, treatment was stopped, which was only possible in 9.4% of patients after a median of 89 wk. In 82% of the remitters a clinical relapse occurred after a median of 22.4 wk and only 1.7% of all included patients were able to discontinue therapy in the long term[63]. Another retrospective interval follow-up trial over three years including 51 adult EoE patients, who were initially treated successfully with a swallowed fluticasone inhaler, found a relapse in 91% of these patients after an average of nine months after therapy was stopped. 69% of patients repeated treatment with the steroid inhaler at least once[68]. Dellonet al[69]reported recurrence of symptoms after initial successful remissioninduction therapy in 33 of 58 patients (57%) before one year. At symptom recurrence, 78% of patients were found to have histologic relapse. Additionally, in the very recently conducted double-blind, placebo-controlled maintenance trial (Eos-2 trial) with budesonide orodispersible tablets (BOT), EoE-patients in remission (n= 204) received either 1 mg BOT BID, 0.5 mg BOT BID or Placebo BID. After 48 wk of treatment, only 20.6% of patients in the placebo group were still in clinical remission, 89.7% were proven to have a histological relapse (intention-to-treat-analysis)[70]. These data show, that long-term-treatment of EoE to maintain remission would make much sense.

STCs have been mainly successfully evaluated for short-term treatment of EoE but there is only limited data for long-term-treatment available. A retrospective cohort study on 206 patients with a median follow-up time of five years showed that an increased frequency of use of swallowed topical steroids was associated with a lower risk for bolus impactions[71]. Another retrospective study which evaluated the longterm efficacy of STC in 229 adult EoE patients over four years showed significantly higher proportions of patients on STCs in clinical remission (31.0%) compared to patients off STCs (31%vs4.5%,P< 0.001). The same was described for endoscopic remission (48.8%vs17.8%,P< 0.001), histologic remission (44.8%vs10.1%,P< 0.001), and complete remission (16.1%vs1.3%,P< 0.001). Higher cumulative doses of STCs and longer durations of treatment were associated with higher proportions of clinical and complete remission[72]. One small prospective study in 10 patients who received 1 year of treatment with fluticasone propionate showed a significant reduction of esophageal subepithelial fibrosis compared to controls[73]. Recently, results of an openlabel extension study with the aforementioned BOS have been published. 82 EoEpatients who completed 12 wk of either budesonide (2 mg twice daily) or placebo therapy received another 24 wk budesonide (2 mg once daily for 12 wk, with optional dose increase (1.5-2 mg twice daily) for 12 wk thereafter). 42% of the therapy responders maintained a histologic remission during the open-label extension and 4% of non-responders gained response[46].

Only a few placebo-controlled EoE-maintenance trials exist: Straumannet al[74]reported 28 adult patients who, after having responded to swallowed budesonide, were randomized to continue low-dose budesonide at 0.25 mg twice daily or to receive placebo for one year. Histological remission (< 5 eosinophils/hpf) after one year was only achieved in 36% of the budesonide patients and in 0% of the placebo patients, but this difference was not significant. The comparably low number of long lasting clinical remission was most likely due to underdosing of the used steroid treatment (only 0.5 mg/d), moreover no specific esophagus-targeted formulation was used[74]. Highquality data are available from the aforementioned Eos-2 trial, comparing maintenance therapy with 1mg BOT BID, 0.5 mg BOT BID or Placebo BID over a period of 48 wk in EoE patients in clinical-histopathological remission. As previously alluded, EoE relapse was high in the placebo-group. Placebo treatment was significantly inferior to both BOT-treatment groups, where maintenance of clinic-histological remission (defined as absence of clinical relapse, lack of histological relapse, absence of food impaction, no need for endoscopic dilation therapy and no premature withdrawal for any reason) was described in 75% (1 mg BID) and 73.5% (0.5 mg BID) of patientsvs4.4% (placebo BID)[70]. Additionally, the BOT maintenance treatment was shown to maintain and even to further improve patients’ quality of life (evaluated with the EoEQoL-A) compared to the placebo group[75]. The 0.5 mg BOT is expected to be officially approved for EoE maintenance therapy in 2020.

POSSIBLE SIDE EFFECTS OF STCS

Generally, STC-treatment in EoE has been found to be well tolerated, with a good safety profile. Most common side effect is candida esophagitis which was estimated to occur in 8.7% of patients[54]. For the newest, esophagus-targeted formulations candida esophagitis in short-term treatment was described for the orally disintegrating fluticasone tablet in a total of 9.4% of patient (up to 20% in the highest dose group – 3 mg BID)[59], for the mucoadherent BOS (2 mg BID) in 2% of patients[44]and for the BOT (1 mg BID) in 10% of patients[50]. In the long-term therapy, esophageal candidiasis was described in 10% of patient with BOS-treatment (for a total of 24 wk, at least first 12 wk 2 mg/d)[46]. For treatment with BOT clinically suspected symptomatic candidiasis was described in 11.8% of patients in the 1 mg BID group, with histological confirmation only in 2.9%. In the 0.5 mg BID group, there was suspected esophageal candidiasis in 16% of patients. Histological confirmed candidiasis was present in 7.4% of patients[70]. However, most esophageal candidiasis-cases are asymptomatic and usually only incidentally detected at follow-up endoscopy. If candida esophagitis is suspected, histologically confirmation should be carried out; particularly eosinophilic microabscesses can mimic white candida plaques. Antifungal treatment with either fluconazole or nystatin over 7-14 d should be performed[3].

As shown in asthma-patients, long-term use of high-dose topical steroid therapy may cause systemic side effects such as impaired growth in children, decreased bone mineral density, skin thinning and bruising, and cataracts[76]. Hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal-axis suppression, measured by reduced serum or urine cortisol levels seems to correlates with the occurrence of systemic side effects. All aforementioned clinical trials on topical steroids for EoE-treatment (short- and longer-term) have not found relevant changes in cortisol levels or even systemic cortisol side effects. However, one pediatric study reported adrenal suppression, which was measured by a low-dose adrenocorticotropin stimulation test, in 10% of children treated with swallowed glucocorticoids for > 6 mo. However, adrenal suppression was only found in those children treated with fluticasone > 440 μg/d compared to lower doses of fluticasone. After discontinuation of fluticasone the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis recovered in all children[77]. Another small series reported in 6/14 children (43%) treated with OVB suboptimal cortisol stimulation measured by ACTH stimulation test independently of treatment duration[78]. Thus, measurement of morning cortisol levels as well as close observation for potential systemic steroid side effects should be done on a regular basis in all patients receiving long-tem topical steroid treatment of EoE. Additional ACTH-stimulation test might be helpful in unclear cases.

PRACTICAL MANAGEMENT

STCs can be regarded as the medical treatment of choice for most EoE patients. Recommended standard regimes include either the use of budesonide 2 mg/daily or fluticasone 880-1760 μg/daily in adults and budesonide 1mg/daily or fluticasone 88-440 μg/daily in children, respectively[2]. Most effective are esophagus-targeted formulations of topical steroids, but so far, only in the EU, the BOT (1 mg BID 6-12 wk) is officially approved for EoE remission induction therapy. In the rest of the world esophagus-targeted formulations may only be available within studies. So, in daily practice in most of the world non-esophagus-targeted formulations of STCs will still have to be used. Regarding this scenario, Dellonet al[47]recently compared the efficacy of budesonide vs. fluticasone for initial treatment of EoE in a randomized controlled trial. For a period of 8 wk 129 EoE-patient were randomized to treatment either with an OVB (aqueous budesonide mixed into a slurry with a sugar substitute, 1 mg BID) plus a placebo inhaler or with a fluticasone inhaler (MDI, swallowed, 880 g BID) plus a placebo slurry. Both STCs resulted in a significant decrease in esophageal eosinophil counts (histologic response with budensonide: 71%; with fluticasone: 64%) and improved dysphagia and endoscopic features. The rates of esophageal candidiasis were comparable (OVB: 12%, MDI: 16%, all asymptomatic). There was one event of food-impaction in the MDI-group, however this was recorded in a patient who had stopped taking medications during the 8-wk treatment phase. Overall, OVB was not superior to MDI, so either one can be regarded as an acceptable treatment for EoE. However, the OVB involves increased patient or pharmacy effort to mix, as well as added costs[47].

For inducing remission of the disease, treatment duration of 6 to 12 wk is initially recommended. As symptoms alone cannot safely predict therapy success, endoscopy with biopsies for histopathological evaluation is still mandatory. To avoid repeated endoscopic procedures much of an effort has been put in the evaluation of potential non-invasive biomarkers but until today no biomarker has been found reliable enough to replace endoscopy[79]. Best results most likely exist for the easy and cheap to measure but rather non-specific serum absolute eosinophilic count, which thus might be helpful for therapy monitoring in a least some EoE patients[80,81].

For the reasons already stated above, namely the chronic inflammatory and fibrosing character of EoE, long-term treatment seems highly advisable for most patients. Given the results of the long term maintenance study with oral orodispersible budesonide, the dosage of STCs in this scenario can be chosen lower than dosage used for inducing remission (in this case 0.5 mg BID)[70]. Further studies are needed to define the optimal lowest dosing for maintenance of remission. Furthermore, there is no data about when sustained clinical remission can be expected and long-term therapy can possibly be stopped. If either an interval treatment with regular therapy breaks might be superior to a continuous application of topical steroids, is under current investigation. Nevertheless, long-term treatment of EoE with STCs can be considered safe and particularly systemic corticosteroid side effects rarely occur. However, only a few safety data are available yet. Thus, careful surveillance of possible local side effects (particularly candidiasis) and unlikely systemic side effects (particularly adrenal suppression) have to be performed. This includes a regular clinical and endoscopic assessment as well as monitoring of morning cortisol levels and physical and ophthalmologic examinations.

CONCLUSION

In summary, response rates of remission induction therapy with STCs are very high, especially for esophageal targeted formulations and thus can be regarded as therapy of choice for the majority of EoE patients. But what are the alternatives, particularly if this treatment fails? Beside the other first-line options such as PPIs and elimination diets emerging drugs including antibodies that specifically target key players in EoE inflammation pathways like IL-4, IL-5 or IL-13 signaling are currently under development and investigation.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年36期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年36期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and kidney function: Effect of HSD17B13 variant

- Major gastrointestinal bleeding and antithrombotics: Characteristics and management

- Artificial intelligence in gastric cancer: Application and future perspectives

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor protects mice against hepatocellular carcinoma by ameliorating intestinal dysbiosis and attenuating inflammation

- SMARCB1/INI1-deficient pancreatic undifferentiated rhabdoid carcinoma mimicking solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: A case report and review of the literature

- Solitary peritoneal metastasis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case report