Axonal regeneration and sprouting as a potential therapeutic target for nervous system disorders

Katherine L. Marshall, Mohamed H. Farah

Abstract

Key Words: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; axonal regeneration; dying-back axonopathy;in vitro neuromuscular junction; iPSC-derived motor neurons; microfluidic device; motor axon sprouting

Introduction

Axonal damage is a common feature of traumatic injury and neurodegenerative disease. The capacity for axons to regenerate and to recover functionality after injury is a phenomenon that is seen readily in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), but axonal regeneration in the central nervous system (CNS) is limited. Factors that are both intrinsic and extrinsic to CNS neurons contribute to their reduced capacity to regenerate following an insult, which often leaves many axons disconnected from their targets (Goldberg and Barres,2000; Fawcett, 2020), resulting in irreversible functional impairment. In neurodegenerative diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), impairment is progressive as distal axons disconnect from their targets, neurons die, and any active repair mechanisms are overwhelmed. Insight into mechanisms that impact axonal regeneration in injury and disease may contribute to the ability to discover novel drug targets to improve regeneration to attain function recovery in the many cases in which axonal repair mechanisms are inactivated and/or insufficient.

Activation of pro-regenerative transcriptional programs is limited in CNS neurons after an axonal injury. In the PNS,HDAC5, a histone deacetylase that inhibits expression of regeneration associated genes (RAGs), is rapidly exported from the nucleus following axonal injury in order for neurons to regenerate their axons (Cho et al., 2013). Once HDAC5 exits the nucleus, expression of RAGs is robust and leads to the expression of proteins that support axonal regeneration such as cell adhesion molecules, cytoskeleton components,neurotrophic factors, and GAP43 (Allodi et al., 2012).Following injury, CNS axons do not activate pro-regenerative programs to the same degree (Fernandes et al., 1999), which may be due in part to epigenetic silencing of RAGs (Weng et al., 2017), limiting their capacity to regenerate. The CNS has different repressive epigenetic mechanisms than the PNS,as recent studies have demonstrated that HDAC5 remains localized to the cytoplasm before and after injury in retinal ganglion cells (Pita-Thomas et al., 2019).

Following axon injury, the distal portion of the severed axon undergoes Wallerian degeneration, where it fragments and degenerates in a process mediated by Sterile Alpha and TIR Motif Containing 1 (Sarm1; Osterloh et al., 2012; Essuman et al., 2017; Krauss et al., 2020). Sarm1 is activated following injury in both the PNS and CNS, and inactivation of SARM1 protects axons from degeneration and preserves function(Krauss et al., 2020). In recent years, it has become clear that the Wallerian degeneration pathway is active in both injury and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and ALS (Coleman and H?ke, 2020; Krauss et al., 2020).

Additionally, conditions within the tissue environment of the CNS are not permissive for axonal regeneration (Fawcett,2020). The influence of the extracellular environment and non-neuronal cell types is a major contributor to axonal regeneration as demonstrated by several pivotal papers which used nerve transplant experiments to demonstrate that CNS axons within the context of a PNS environment can regenerate(Richardson et al., 1980, 1984; Benfey and Aguayo, 1982).

Non-neuronal cell types in the CNS substantially contribute to creating an extracellular environment that is non-conducive to effective axonal regeneration. Myelin debris and myelinassociated proteins left from degenerating axons contribute to stifling of regeneration in the CNS. Clearance of this debris by microglia and macrophages that enter the CNS is slow (George and Griffin, 1994; Lloyd et al., 2017). Myelin associated inhibitory molecules expressed by oligodendrocytes, such as Nogo-A, myelin associated glycoprotein, and oligodendrocytemyelin glycoprotein, interact with axonal receptors to activate RhoA/ROCK signaling (Geoffroy and Zheng, 2014). RhoA/ROCK signaling inhibits axonal outgrowth, blocking this pathway accelerates CNS axonal outgrowthin vivo(Fujita and Yamashita, 2014). Other non-neuronal cell types of the CNS secrete molecules inhibitory to axon outgrowth,especially in the glial scar. In addition to containing the aforementioned inhibitory myelin-associated molecules, the glial scar is physically distinct from the surrounding tissue and is unfavorable to regenerating axons (Moeendarbary et al.,2017). Reactive astrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursors within the scar secrete chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans(CSPGs), which have been demonstrated to inhibit CNS axon regeneration and sprouting (Bartus et al., 2012; Silver et al.,2015). Sema3a, an repulsive axonal guidance molecule, is expressed in the glial scar and has been demonstrated to inhibit axonal regeneration through ROCK signaling (De Winter et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2020).

In contrast, non-neuronal cell types in the PNS contribute to creating a post-injury environment that is more favorable for axonal regeneration. Macrophages and neutrophils that enter the injured PNS are the major contributors to the clearance of myelin debris, which is faster than microglial debris clearance in the CNS (George and Griffin, 1994; Lindborg et al., 2017).Schwann cells gain phagocytic activity after injury and, along with macrophages, contribute to enhanced clearance of inhibitory myelin debris in the PNS (Scheib and H?ke, 2016;Lutz et al., 2017). Both myelinating and non-myelinating Schwann cells transition to a repair Schwann cell phenotype by rapidly adopting transcriptional programs, driven by the transcription factor c-JUN (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2012), that allow them to form tubes (bands of Büngner) that guide the paths of regenerating axons towards target tissue (Scheib and H?ke, 2013). Schwann cells adopt distinct transcriptional profiles that aid in sensory or motor axon regeneration, which help guide axons to reinnervate the correct targets (H?ke et al., 2006).

Denervated target tissue in the periphery also plays a role in encouraging the growth of axons by secreting pro-regenerative molecules. Resident macrophages in the skin have recently been demonstrated to contribute to regeneration of sensory axons after injury (Kolter et al., 2019), underscoring the contributions of non-neuronal cell types within target tissue to axonal regeneration. Among other neurotrophic factors,insulin-like growth factor is secreted from denervated skeletal muscle (Pockett and Slack, 1982; English, 2003), and has been demonstrated to speed motor axon regenerationin vivo(Caroni and Grandes, 1990; Near et al., 1992). Ultimately,maintenance of the target tissue landscape during a period of denervation is crucial for reinnervation of target tissue and restoring function. Neuromuscular junctions (NMJs)degenerate following extended periods of denervation (Ma et al., 2011; Sakuma et al., 2016). If the delay is too long,atrophy and degeneration of muscle fibers can prevent functional recovery even if some NMJs are reinnervated(Wu et al., 2014). It has been demonstrated in several injury models that acceleration of peripheral nerve regeneration improves functional recovery after injury, but there may be a critical window of time during which motor endplates can be reinnervated (Ma et al., 2011; Farah, 2012; Tallon et al.,2020). Functional peripheral motor axon regeneration was accelerated by an overexpression of a regeneration associated protein, HSP27, but only for a limited time, after which fully regenerated motor axons failed to successfully reinnervate motor endplates (Ma et al., 2011).

Several factors underlie the substantial discordance in the functional regeneration capacity of CNS and PNS axons.Examination of both intrinsic mechanisms of regeneration and extrinsic conditions that encourage the regeneration of axons in the CNS and PNS may lead to the discovery of new therapeutic interventions for injury and disease, but drug discovery for neurological diseases has an added layer of complexity. To maintain homeostasis, both the CNS and the PNS have barriers of endothelial cells connected by tight junctions that limit the accessibility of axons to many drugs.The blood-brain-barrier to the CNS is one of the greatest challenges to drug discovery. However, the microvasculature associated with the blood-nerve barrier is more permeable than the blood-brain barrier and is permissive to drug compounds (Orte et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2018). Many drugs have demonstrated modulatory effects on peripheral nerve regeneration in preclinical injury models (Bota and Fodor,2019). Targeting distal axons in the PNS to enhance repair programs represents an exciting opportunity to develop treatments not only for peripheral nerve injury, but also several neurological disorders that exhibit distal axonopathy outside of the CNS. Through increased understanding of the barriers to regeneration in the CNS, in addition to continued advancement of drug delivery and targeting methods, drugs can be developed to enhance axonal regeneration in the CNS following insult.

In this review, we will discuss the possibility of using drugs that enhance axonal regeneration and compensatory sprouting as a therapeutic strategy for nervous system disorders,specifically Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). In addition,we will discuss approaches to study axonal sprouting and regenerationin vitrousing relevant cell types derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

An electronic search of NCBI PubMed database for literature describing axon regeneration and innervation of NMJs from 1945-2020 was performed. The following key words were used, in various combinations, and results of the literature search were manually screened for relevant material: axonal regeneration, motor axon sprouting, dying-back axonopathy,amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), iPSC-derived motor neurons, microfluidic device, andin vitroneuromuscular junction.

Distal Axon Degeneration and Synaptic Disconnection are Common Features of Neurologic Diseases

Nervous system disorders are extremely prevalent and will continue to increase in frequency as the population ages(GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators, 2019). In addition,there is evidence that die-back of motor axons is a significant contributor to age-related muscle atrophy and weakness(Chung et al., 2017). Treatments that target regenerating axons and augment the compensatory efforts of the PNS to reinnervate their target tissues have the potential to provide substantial benefits to patients from all facets of society,especially an aging population.

Though many different types of neurons are affected in various diseases, in many cases synaptic disconnection of axons from their targets is a core pathological feature(Henstridge et al., 2016). Dying-back axonopathy, a process in which axonal degeneration starts from the most distal part of the axon and progresses towards the cell body, occurs in many neurological disorders. Axonal die-back from the target or synaptic dysfunction causes the loss of the functional synapse before the death of the neuron itself (Fischer et al.,2004; Han et al., 2010; Dadon-Nachum et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2012; Moloney et al., 2014; Tampellini, 2015; Valad?o et al., 2018). Maintenance of current neuronal connections or establishment of new connections often enhances the longevity of neurons; synaptic activity can stimulate expression of pro-survival programs in neurons and inhibit genes linked to apoptosis (Bell and Hardingham, 2011). This implicates distal axons as potential sites for early therapeutic intervention for neurological disorders, whether it be by preserving synaptic connectivity or encouraging reconnection of axons with their targets.

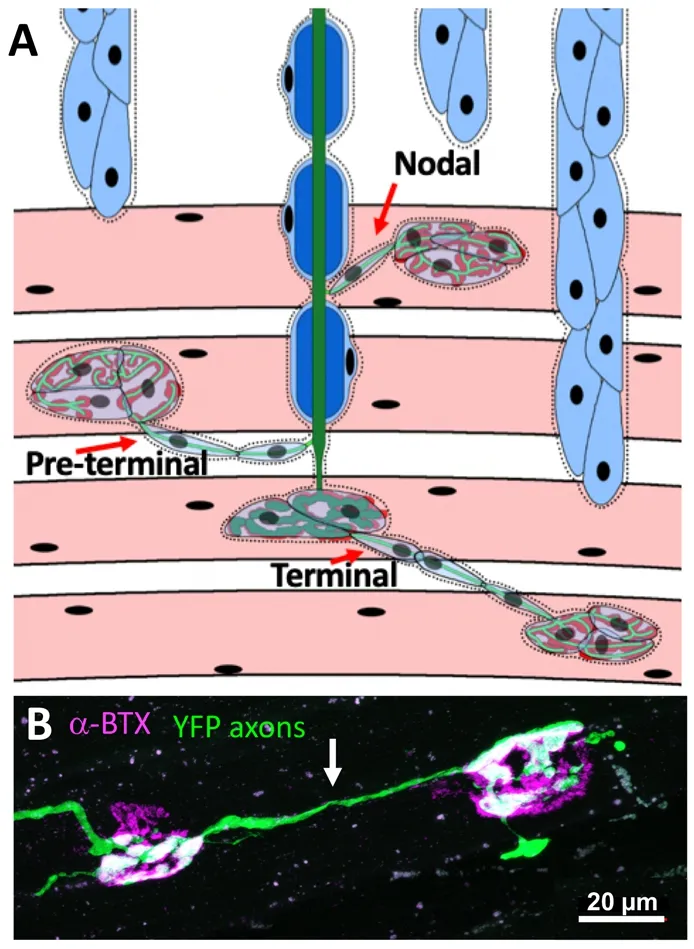

ALS is a devastating disease, with a median life expectancy of 24-50 months (Longinetti and Fang, 2019), where dyingback axonopathy is a prominent characteristic (Fischer et al., 2004). Progressive dying-back of motor axons and death of motor neurons in ALS leads to muscle wasting and death(Fischer et al., 2004; Dadon-Nachum et al., 2011; Tallon et al.,2016). Muscle denervation long precedes motor neuron death(Fischer et al., 2004). Axonal regeneration and outgrowth is a process of interest in the context of muscle denervation because intact axons that neighbor NMJs that have been vacated in the disease process can sprout in attempt to reinnervate them (Gordon et al., 2004). This phenomenon of compensatory sprouting, to a limited degree that is insufficient to prevent disease progression, is observed both in ALS patients and transgenic mouse models of ALS (Figure 1; Pinelli et al., 1991; Frey et al., 2000; Tallon et al., 2016;Martineau et al., 2018, 2020). There is a possible window of opportunity where existing motor units could reinnervate NMJs from which axons have retracted. If a drug could overcome the limits to plasticity at the NMJ, compensatory reinnervation may slow symptom progression to a much more meaningful degree.

Compensatory Sprouting as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Sprouting of motor axons and reinnervation of denervated NMJs can lead to functional motor recovery (Gordon et al.,2004). Early studies that described compensatory sprouting utilized rodent partial nerve injury models where only some axons were severed and others left intact. Electrophysiological recordings from target muscle showed that the intact fibers made new connections with denervated muscle even before severed nerve fibers could regenerate long enough to reach the muscle (Harreveld, 1945), which was confirmed by histology (Hoffman, 1950). Further partial nerve injury experiments demonstrated that after early development,motor unit territory expands after injury by axonal sprouting and NMJ remodeling (Fisher et al., 1989). Under nonpathologic conditions, one axon terminal innervates a single NMJ, but motor units can be enlarged 5-8 times their original size through axonal sprouting (Dengler et al., 1990; Yang et al.,1990; Bromberg et al., 1993; Gordon et al., 2004).

Figure 1|Compensatory axonal sprouting and reinnervation of NMJs.(A) Diagram illustrating types of compensatory sprouting. Terminal sprouts emerge from the axon terminal at the NMJ. Pre-terminal sprouts grow from the axon area immediately proximal to the NMJ. Nodal sprouts emerge from the nodes of Ranvier off the main axon branch. (B) Terminal sprout (indicated by arrow) in the diaphragm of a SOD1G93A mouse expressing YFP (green) in axons. α-Bungarotoxin (α-BTX, magenta) labels the post-synaptic NMJ. NMJs:Neuromuscular junctions.

Early documentation of disease-associated compensatory axonal sprouting of PNS axons and reinnervation of NMJs was demonstrated in the case of polio infection. Poliovirus can infect and kill spinal motor neurons (Halstead, 1998), leading to paralysis in severe cases. Following acute infection, axons of surviving motor neurons sprout and reinnervate neighboring NMJs. This adaptive sprouting and subsequent enlargement of motor units has been shown to sustain muscle function for over 25 years, suggesting that adaptive sprouting may be able to compensate for denervation to some degree in diseases with muscle denervation (Gordon et al., 2004). In post-polio syndrome, where polio survivors develop progressive muscle weakness, often decades after infection, it is thought the substantially enlarged motor units can no longer keep up with metabolic demand for such an extended period of time and begin to die (Halstead, 1998). In the CNS, reparative axonal sprouting has been studied after stroke, and is correlated with motor recovery (Carmichael et al., 2017).

There is evidence of motor axon sprouting in the context of ALS (Fischer et al., 2004; Bruneteau et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2016). Certain subpopulations of motor neurons are more susceptible in ALS, which are also the most reticent to sprout (Frey et al., 2000). Electrophysiological recordings from individual ALS patients and healthy controls indicate that ALS patients at symptomatic stages have a severe depletion of motor units, but the surviving motor units in ALS patients are significantly larger than healthy control patients (Howells et al., 2018). Enlargement of motor units in ALS patients is presumably due to sprouting of intact axons and reinnervation of denervated muscle fibers, which is supported by evidence of fiber-type grouping in ALS patients (Jensen et al., 2016).Similar to what was observed in survivors of polio, it seems that sprouting of motor axons and reinnervation of muscle fibers during the disease course compensates for the loss of motor units until the repair processes are overwhelmed.However, ALS pathogenesis is efficient in overwhelming compensatory sprouting, and motor units in ALS are rarely enlarged to the degree that is seen in more slowly progressive motor neuron disease (Dengler et al., 1990; Bromberg et al., 1993; Daube, 2000; de Carvalho and Swash, 2016).When specifically examining sprouting in ALS patient muscle biopsies, poly-innervated NMJs correlated with a lower disease progression rate, and were more often found longterm ALS survivors (Bruneteau et al., 2015). A strategy to slow progression of muscle denervation and resulting weakness in ALS would be to retain pre-existing innervation of NMJs and augment compensatory sprouting in order to reinnervate NMJs throughout the course of disease.

It has been predicted that the number of ALS cases will increase globally through 2040 (Arthur et al., 2016; Longinettiand Fang, 2019). In the United States, costs associated with ALS were estimated to be over one billion dollars annually(Larkindale et al., 2014). There are two drugs currently approved to treat ALS, Riluzole and Edaravone. Riluzole, which was approved by the FDA in 1995, only extends life by a few months and do little to improve quality-of life (Petrov et al.,2017). Edaravone, recently approved in 2017, did not show efficacy in a general ALS population, but post-hoc analysis showed that there was mild improvement in a clinical subset of patients (EDARAVONE (MCI-186) ALS 16 STUDY GROUP,2017; Maragakis, 2017). Any drugs capable of improving the quality-of-life for ALS patients are urgently needed. Axonal sprouting that leads to functional reinnervation of NMJs may enhance life quality and increase lifespan in ALS. Though this approach does not address the mechanistic underpinnings of the disease and would not lead to a cure, there is a possibility that if plasticity at the NMJ could be improved, the progression of muscle weakness could be delayed. Patients with more slowly progressing forms of ALS, about 10% of ALS patients (Longinetti and Fang, 2019), where the post-diagnosis lifespan is often a decade or more, might benefit greatly from increased reinnervation throughout the disease course.

Motor Axon Outgrowth in Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

The most studied mouse model of ALS to date is the transgenic SOD1G93Amouse. Most evidence suggests that mutant SOD1 impairs axonal outgrowth and regeneration,with the few exceptions. Adult motor neurons isolated from mice harboring SOD1 mutations (G93A and G85R) have more growth cones and enhanced outgrowth compared to WT neurons (Osking et al., 2019). However, multiple studies have demonstrated SOD1G93Amice to have impaired axonal regeneration after sciatic and facial nerve crush injury(Mesnard et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2018; Schram et al., 2019).mRNA profiling following facial nerve injury in SOD1G93Amice indicates that post- axotomy gene expression changes resemble those that occur after axons have retracted from NMJs during the disease course (Haulcomb et al., 2014).iPSC-derived motor neurons from SOD1G93Amice have reduced neurite length compared to WT (Park et al., 2016),and expression of SOD1G93Ain zebrafish impairs motor axon outgrowth and branching (Sakowski et al., 2012).

Beyond mutations in SOD1, there is extensive evidence that motor axon outgrowth and regeneration are negatively impacted by several ALS disease-causing mutations. Impaired axonal outgrowth has been observed in multiple studies of primary motor neurons cultured from mouse and zebrafish models of ALS, generated through altering expression levels of TDP43, FUS, U1snRNP, or c9RAN proteins (Kabashi et al.,2009, 2011; Fallini et al., 2012; Schmid et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2015). Overexpression of TDP43 reduces axonal outgrowth in primary mouse motor neurons (Fallini et al., 2012). Knockdown and overexpression of mutant TDP43 reduces motor axon outgrowth in zebrafish (Kabashi et al.,2009, 2011; Schmid et al., 2013). Knockdown of FUS, and U1 snRNP (interacts and co-mislocalizes with FUS in ALS patient cells) results in reduced motor axon outgrowth in zebrafish(Kabashi et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2015). Expression of c9RAN proteins in primary mouse neurons results in reduced neurite outgrowth (Zhang et al., 2014). Therefore, it is of great interest to explore whether outgrowth defects induced by distinct ALS-disease causing mutations can be overcome.

Transgenic Approaches to Enhance Compensatory Sprouting in Preclinical Models

A number of transgenic approaches have been explored that report increases in sprouting of motor axons in mouse models of motor neuron disease. Over expression of activating transcription factor 3, a transcription factor that promotes expression of genes that are associated with survival and neurite outgrowth (Seijffers et al., 2006), in SOD1G93Amice improved motor function, muscle force, and delayed disease onset (Seijffers et al., 2014), AAV-transduction of IGF-2 into motor neurons of SOD1 mice improved lifespan, motor behavior, and motor neuron survival, but the authors also observed a markedly increased expression of GAP43 at the NMJ, suggesting that sprouting and reinnervation of NMJs may have also played a role in improving functional outcomes(Allodi et al., 2016). AAV-mediated over-expression of NRG1-I also resulted in improved functional outcomes with a concurrent increase in collateral sprouting (Mancuso et al., 2016). Improved motor function in SOD1 mice was also achieved by genetic ablation of Amyloid Precursor Protein(APP), which may be involved in dampening pathways that encourage sprouting and reinnervation of NMJs (Bryson et al.,2012). There remains a substantial amount of work to discern respective contributions of neuroprotection and increased survival of motor neurons versus compensatory sprouting and improved reinnervation of NMJs in maintaining muscle function and improving outcomes in models of motor neuron disease. In a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA)type III, a more slowly progressing motor neuron disease,compensatory sprouting and subsequent reinnervation of NMJs was able to fully maintain muscle function (Udina et al., 2017). Reinnervated NMJs in SOD1G93Amice were better maintained and were more resistant during the disease course following an early axonal crush injury, suggesting that even as motor units are lost in ALS, there is a potential to enlarge and strengthen surviving connections in order to retain muscle function (Sharp et al., 2018). These experiments suggest that not only can compensatory sprouting result in retention of motor function in motor neuron disease, but that this endogenous capacity can also be boosted in a disease context.

Pharmacologic Approaches to Enhance Compensatory Sprouting in Preclinical Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

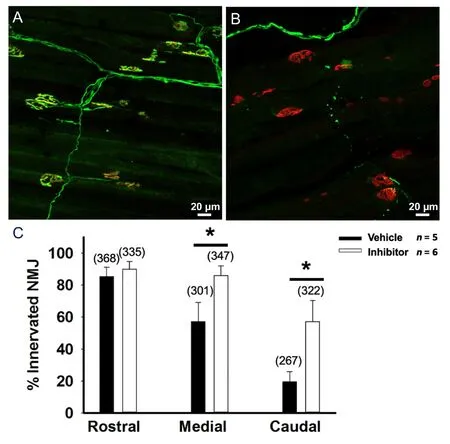

While transgenic approaches have provided preliminary support for the idea that increasing motor axon sprouting may improve retention of motor function and slow motor neuron disease progression, these avenues are not easily translated to the clinic. We have recently shown that pharmacological inhibition of beta-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE1), a membrane-bound aspartyl protease with over 60 identified substrates, improves compensatory sprouting in both nerve injury models and SOD1G93Amice. Previously, we discovered that when BACE1 is inhibited the rate of axonal regeneration is significantly improved (Farah et al., 2011). Our data suggest that there is an inverse relationship between BACE1 levels and regeneration in the PNS (Tallon and Farah, 2017; Tallon et al., 2017). This led us to pursue more clinically relevant pharmacological inhibition of BACE1 in injury models, and to test the hypothesis that motor neuron disease outcomes may be improved by enhanced outgrowth of peripheral motor axons. Treatment of wild-type mice with BACE inhibitor resulted in hastened regeneration, increased innervation of NMJs, and faster motor recovery following a nerve crush injury(Tallon et al., 2020). Following a partial nerve injury in wildtype mice, treatment with BACE inhibitor resulted in greater numbers of axoterminal sprouts. SOD1G93Amice treated with BACE inhibitor for both 1 and 2 months had fewer denervated NMJs and improved motor electrophysiology at early stages of disease (Tallon et al., 2020). Four-month-old SOD1G93Amice also had a greater proportion of innervated NMJs following 3 months of BACE inhibitor treatment (after starting treatment at 1 month of age, Figure 2). As we had seen in the wildtype partial injury model, SOD1G93Amice treated with BACE inhibitor had significantly greater numbers of axoterminal sprouts (Tallon et al., 2020). This is a promising proof-ofconcept that drug modulation of plasticity at the NMJ may be a viable therapeutic target for symptom mitigation in motor neuron disease. Further support of this notion comes from pharmacologic inhibition of Rho-kinase signalling, using a small molecule inhibitor of RhoA, which led to enhanced motor axon regeneration after injury and increased reinnervation of NMJs in SOD1G93Amice (Joshi et al., 2019).

BACE1 inhibitors have been under extensive development for decades (Imbimbo and Watling, 2019). They have been tested in phase III clinical trials for Alzheimer’s Disease, and thus have safety and pharmacodynamics data that are wellestablished (Kennedy et al., 2016). Recent termination of the phase III clinical trials was due to futility, and BACE1 inhibitor adverse effects were mild (Egan et al., 2018, 2019). Thus, the inhibitor may be repurposed rapidly if it shows preclinical efficacy in the context of ALS (Tallon and Farah, 2017; Tallon et al., 2020). There may be a therapeutic window of opportunity in ALS when peripheral axons are primarily affected, and inhibition of BACE1 may be effective in slowing denervation.Additionally, there is a possibility that BACE1 inhibitors may be administered at a lower dose in ALS than what was necessary for Alzheimer’s disease because the new intended site of action is in the comparatively more accessible PNS.

However, some potential treatments that increased sprouting in preclinical models did not slow disease progression when administered to ALS patients. Early ALS clinical trials with gangliosides, which were demonstrated to increase axonal sprouting in animal models, ultimately showed no efficacy(Bradley et al., 1984; Lacomblez et al., 1989; Bradley, 1990).Increased levels of insulin-like growth factors (IGF) had also been demonstrated to increase sprouting of peripheral motor axons (Caroni and Grandes, 1990). Expression of IGF-1 in SOD1G93Amice significantly increased lifespan and motor neuron survival (Kaspar et al., 2003; Dobrowolny et al., 2005),but compensatory sprouting was not specifically examined.Motor neuron protection was attributed to inhibition of motor neuron apoptosis pathways, attenuation of the pathogenic astroglial activation in the spinal cord, and stabilization of NMJs. Despite neuroprotection in preclinical models, IGF treatment failed to improve patient outcomes in clinical trials(Borasio et al., 1998; Sorenson et al., 2008; Saccà et al., 2012).More recently, Nogo-A seemed a promising target because its expression correlated with denervation disease severity and in ALS patients (Jokic et al., 2005; Bruneteau et al., 2015).Inhibition of Nogo-A enhances regenerative sprouting several models of spinal cord and brain injury (Z?rner and Schwab,2010; Mohammed et al., 2020). Treatment with anti-Nogo-A antibody slowed disease progression in SOD1G93Amice when administered in an early symptomatic disease stage, but it was unclear whether the benefits to muscle force and weight were due to compensatory sprouting and reinnervation of NMJs or enhanced neuroprotection of lower motor neurons (Bros-Facer et al., 2014). However, in a phase 2 trial, the anti-Nogo-A antibody (Ozanezumab) did not show efficacy compared to placebo in ALS patients (Meininger et al., 2017).Importantly, this approach may be more broadly applicable for symptom mitigation for a wide variety of diseases and injuries. Peripheral nerve damage caused by disease or injury is a prevalent neurological problem that currently affects about twenty million Americans (Grinsell et al., 2014).Surgical treatments for injury are not effective in the majority of cases, and life-long impairment is common (Palispis and Gupta, 2017). In the case of neurodegenerative disease,compensatory sprouting of axons is insufficient to compensate for progressive synaptic disconnection and leads to rapid progression of symptoms. There are currently no drugs that act by enhancing regeneration of peripheral nerves, and there are no other non-surgical treatments that target peripheral nerve injury (Palispis and Gupta, 2017).

Figure 2|Prolonged treatment with BACE inhibitor in SOD1G93A mice reduces denervation in cutaneous maximus muscle.Cutaneous maximus muscle of a SOD1G93A mouse collected at 4 months of age following 3 months of treatment with (A) BACE inhibitor and (B) vehicle showing more innervated NMJs in inhibitor treated mice. Mice expressed YFP (green) in axons, α-Bungarotoxin (α-BTX, red) staining labels the postsynaptic NMJ. (C) Quantification of the number of innervated NMJs between vehicle and inhibitor treated mice. Vehicle n = 5, inhibitor n = 6. Numbers in parenthesis indicate total number of NMJs counted. Bars represent the mean ± standard error. Statistical significance was calculated using a onetailed Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05. NMJs: Neuromuscular junctions. Figure 2 is created by the authors.

A number of other neurological disorders exhibit early pathology in distal peripheral axons. Targeting axonal regeneration and sprouting could be used in the context of many other nervous system disorders, such as Charcot-Marie tooth disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease, all of which exhibit dying-back axonopathy (Fischer et al., 2004; Fischer and Glass, 2007; Han et al., 2010; Chu et al., 2012). Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT), which refers to a group of commonly inherited sensory and motor neuropathies, often causes significant disability due to dieback of PNS axons (Nave et al., 2007). Though most cases of CMT are primary demyelinating forms of CMT, the slowed nerve conduction velocity that results from demyelination does not cause neurological impairment on its own; distal axon die-back and denervation of muscle tissue cause the most clinical impairment (Nave et al., 2007). Intramuscular injection of AAV to transduce neurotrophin-3 has been explored in a CMT mouse model (Sahenk et al., 2014). It was demonstrated to increase motor axon sprouting and reinnervation, and has lead to a clinical trial set to begin this year (Sahenk and Ozes, 2020).

Other disorders that are classically thought of as CNS disorders have early pathologic synapatic disconnection or peripheral axonopathy. Presymptomatic die-back of peripheral motor axons and NMJ degeneration has been documented in a mouse model Huntington’s disease (Wade et al., 2008; Valad?o et al., 2018). Parkinson’s disease, which is characterized by death of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and neuronal inclusions containing α-synuclein, also has early pathology in peripherally located axons. In recent years, it has been demonstrated that α-synuclein accumulates in the enteric nervous system and vagus nerve prior to the onset of motor symptoms (Hilton et al., 2014; Chung et al., 2016; Del Tredici and Braak, 2016). It is possible that early intervention in the gut and peripheral axons of the enteric nervous system may be a promising avenue for Parkinson’s Disease treatment.

Investigating the Distal Axon and Modeling Regeneration with Human Neurons in vitro

Though therapeutic options for ALS patients are presently lacking, motor neurons derived from iPSCs have already been instrumental in elucidating the potential molecular basis of ALS pathogenesis and for testing potential therapeutic compounds on human cells (Egawa et al., 2012; Kiskinis et al., 2014;Wainger et al., 2014; Richard and Maragakis, 2015). Many relevant questions about human iPSC-derived motor neurons(hMNs) remain, especially pertaining to the distal axon andin vitroinnervation of myofibers. Because peripherally located axons are so often the site of early pathologic changes in neurodegenerative disease, interrogating the distal axon of human neurons is important for developing relevantin vitromodels and finding treatments that can impact distal axon biology. The tremendous advances in differentiation techniques and compartmentalized co-culture systems have led to the possibility of exploring approaches to enhance axonal regeneration and sproutingin vitro.

Autopsy samples from ALS patients indicate that an early event in ALS pathogenesis is dying-back of motor axons and denervation of NMJs; therefore, it is important to determine the capacity for compensatory outgrowth and maintenance of NMJs by distal motor axons and how that could be affected by specific mutations. Patient-derived iPSCs are powerful resources for both investigation of pathogenesis and testing of potential therapeutic agents. ALS patient-derived hMNs have revealed insights into mutation-specific pathogenesis (Chen et al., 2014; Kiskinis et al., 2014; Wainger et al., 2014; Cooper-Knock et al., 2015). While hMNs are poised to overcome some of the limitations of animal models, the length of axons,regenerative capacity, and mutant-specific innervation of NMJs by these human neurons is not well-characterized.

It is of utmost importance in the effort to use human cells to study events surrounding sprouting and NMJ maintenance. It is well-documented that NMJs are morphologically different between humans and rodents (Slater, 2017). Human NMJs from muscle biopsies have a smaller, less complex, and“nummular” fragmented morphology when compared to rodent NMJs (Jones et al., 2017). In recent years, molecular analysis has underscored that there are fundamental differences that extend beyond NMJs morphology (Jones et al., 2017). When studying the molecular determinants of NMJ stability and reinnervation under pathological conditions,differential protein expression between human and rodent NMJs could be a confounding factor. By using human cells to recreate NMJsin vitro, the potential differential effects of individual disease-causing mutations can be assessed more reliably.

The body of evidence that motor axonal outgrowth is impaired in ALS patient-derived neurons is growing. hMNs from ALS patients (SOD1A4V) had fewer axons and shorter outgrowth compared to controls (Egawa et al., 2012; Kiskinis et al., 2014; Lee and Huang, 2017). After prolonged culture,neurite length declined in hMNs from patients with FUS and TDP-43 mutations (Fujimori et al., 2018). Recently, impaired axonal outgrowth and clear deficits in regeneration were observed in hMNs where TDP-43 had been knocked down(Klim et al., 2019; Melamed et al., 2019). In ALS, TDP43 tends to be excluded from the nucleus and present in cytoplasmic aggregates (Prasad et al., 2019). Under non-pathologic conditions, one of the functions of TDP-43 in motor neurons is to prevent the inclusion of cryptic splice sites in many genes(Ling et al., 2015), including stathmin-2 (Melamed et al.,2019), which is essential for axonal regeneration (Chauvin and Sobel, 2015). Stathmin-2 contains a cryptic polyadenylation site that produces a shortened and nonfunctional mRNA(Melamed et al., 2019). Depletion of TDP-43 in hMNs inhibited axonal regeneration (Klim et al., 2019; Melamed et al.,2019), which could be rescued by transduction of stathmin-2(Melamed et al., 2019). Reduced expression of stathmin-2 was detected in neurons converted from patient fibroblasts with TDP-43 mutations, and in postmortem samples from sporadic ALS patients (Klim et al., 2019; Melamed et al., 2019).

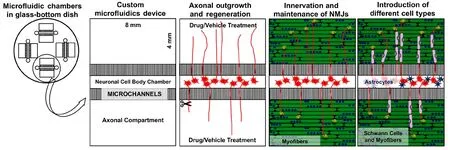

The way in which the hMNs grow and differentiate makes quantification of individual neurite outgrowth difficult because the neurons cluster into circular groups and extend axons to other clumps of neurons like spokes on a wheel. Use of microfluidic chambers, which separate neuronal cell bodies from their axons, allows for efficient axotomy of axons and assessment of regeneration (Klim et al., 2019; Melamed et al.,2019). Microfluidic devices, or compartmentalized co-culture systems, have been used for many decades to specifically interrogate isolated axons (Campenot, 1977; Neto et al.,2016). Microfluidic devices contain microchannels that are small enough to exclude neuronal cell bodies and allow for efficient separation of cell bodies and axons without the need for chemoattractant. Segregating axons from cell bodies makes biological sense in that neuronal cell bodies are often spatially separated from their targetsin vivo, and are congregated in distinct nuclei or ganglia. Lower motor neuron cell bodies reside in the spinal cord, and their distal axons synapse onto muscle that can be a meter away.

Microfluidic platforms may be an effective method to assess the contribution of supporting cell types to axonal regeneration, analyze NMJ formation and maintenance and evaluate potential therapeutics. Spatially separated microfluidic co-cultures of primary, embryonic stem cellderived, or iPSC-derived rodent motor neurons and myofibers readily form functional NMJs (Park et al., 2013; Southam et al., 2013; Ionescu et al., 2016; Uzel et al., 2016; Vilmont et al., 2016; Sala-Jarque et al., 2020). As researchers are more efficiently able to differentiate human cell typesin vitro, they have recognized the importance of establishing a fully human neuromuscular circuit. hMNs can innervate mouse myofibers in microfluidic devices (Yoshida et al., 2015; Yoshioka et al.,2020). In uncompartmentalized co-culture, motor neurons derived from both human embryonic stem cells and iPSCs were shown to form NMJs with cultured human myofibers(Guo et al., 2010; Umbach et al., 2012; Stockmann et al.,2013; Chipman et al., 2014; Demestre et al., 2015; Bakooshli et al., 2019; Picchiarelli et al., 2019). More recently it has been shown that hMNs can innervate human iPSC-derived muscle fibers in spatially separated co-culture (motor unit on a chip)(Osaki et al., 2018, 2020), but much work is left to characterize human iPSC-derived cell types and neuron-muscle co-cultures.Considerable work is left to be done to characterizein vitroneuromuscular connections. Recent work has demonstrated co-cultures with 2D culturing of myofibers results in fewer functional NMJs than co-cultures with myofibers in 3D culture(Bakooshli et al., 2019).

The ability to incorporate and manipulate different cell-types within compartmentalized culture systems is relevant for assessing hMN regeneration and sprouting. NMJ reinnervation is a complex process that does not just involve the motor axon terminal and post synaptic clusters of acetylcholine receptors on the muscle. All motor axons are myelinated by Schwann cells, and it has been known for decades that terminal Schwann cells, which surround NMJs, are critical players in the NMJ remodeling process. Schwann cells sense denervated muscle and extend long processes that serve as a conduit for sprouting axons (Son et al., 1996; Kang et al.,2003, 2014). Abnormal terminal Schwann cell morphology has been observed in mouse models of ALS (Winter et al.,2006; Carrasco et al., 2016), and in muscle biopsies from ALS patients (Bruneteau et al., 2015). Astrocytes have also been demonstrated to play a significant role in ALS pathology(Halpern et al., 2019). iPSC-derived astrocytes from sporadic ALS patients can induce motor neuron degeneration in mouse models (Qian et al., 2017). Furthermore, it has been recently demonstrated that iPSC-derived astrocytes contribute to maturation of hMNsin vitro, underscoring the importance of considering the influence of non-neuronal cells when developing a model (Taga et al., 2019).

Our recent work indicates that compartmentalized microfluidic devices are effective in assessing axonal regeneration of hMNs (Figure 3, unpublished observations). In the devices illustrated in Figure 3, the axonal compartments are open,which allows for easy access to axons for manipulation or axotomy, or addition of relevant cell types. We believe that these compartmentalized microfluidic devices are amenable for testing the effects of drugs on the distal axon and maintenance of target innervation. Similar devices have been used to assess the ability of microglia to phagocytose degenerating CNS axons (Rajbhandari et al., 2014), and assess retrograde axonal transport of varicella-zoster virus (Sadaoka et al., 2016).

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Dying-back axonopathy and synaptic disconnection is a common feature of neurological disorders of both the CNS and PNS. Though the PNS, unlike the CNS, has a natural regenerative capacity that is able to restore some function after injury and retain function for some period of time during the course of neurodegenerative disease, reinnervation of target tissue is often incomplete or overtaken by an aggressive disease course. Potential drugs that can enhance regeneration or compensatory sprouting of peripheral axons may slow progression of symptoms in diseases like ALS by encouraging increased reinnervation of target tissue. While developing drugs that enhance regeneration is more challenging for the CNS, many CNS neurological disorders have early pathology in peripheral axons, which are more accessible for potential drugs.

The use of hMNs and iPSC-derived cell types may prove incredibly impactful for examining the ability of potential drugs to target the distal axon. In the case of ALS, the value of developing human-cell disease models is more apparent considering the differences between human and rodent NMJs, and that animal models thus far have largely failed to translate into successful treatments. Systematic permutations of relevant cells types and hMNs in compartmentalized microfluidic co-culture systems not only have the potential to parse the contributions of disease-causing mutations and specific cell-types to ALS pathogenesis, but may also generate a highly relevantin vitromodel system for neurological disorders. Importantly, compartmentalized microfluidic devices are amenable to the testing of drugs that may act on the distal axon. Recently, three new drugs have entered ALS clinical trials based on promising results in screens of patient iPSCs (Okano et al., 2020). Many neurological disorders exhibit early pathology in distal axons, and use of patient-derived cells in microfluidic devices may be used to find drugs that enhance regeneration and sprouting of axons. Though it is unknown whether compounds that enhance hMN axon regenerationin vitrowill be effective in ALS, microfluidic culture systems may be used to find drugs that encourage reestablishment of synaptic connections by both the PNS and CNS and slow neurological disease progression.

Figure 3|Microfluidic devices that separate neuronal cell bodies from axons.Compartmentalized co-culture systems have the potential to elucidate the effects of drugs,disease-causing mutations, and cell types on distal axons. Axons can grow into either axonal compartment. This system is ideal for investigating axonal outgrowth, innervation of NMJs, and introduction of relevant cell types(astrocytes in the cell-body compartment and myofibers and Schwann cells in the axonal compartment). NMJs: Neuromuscular junctions.

Acknowledgments:We are thankful for valuable discussions/comments and revision provided by Madison James. We are thankful to Carolyn Tallon for drawing the Figure 1A.

Author contributions:Review conception and design: KLM and MHF;data collation, analysis and interpretation: KLM and MHF; paper writing:KLM and MHF; manuscript review and review guiding: KLM and MHF.Both authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:None.

Financial support:This work was supported by the Muscular Dystrophy Association, No. W81XWH1910229 (to MHF) from Department of Defense’s Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program, and Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund, No. 2019-MSCRFD-5093 (to MHF).

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by both authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identicalterms.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- The role of gap junctions in cell death and neuromodulation in the retina

- Don’t know what you got till it’s gone: microglial depletion and neurodegeneration

- Low-dose lipopolysaccharide as an immune regulator for homeostasis maintenance in the central nervous system through transformation to neuroprotective microglia

- Protein post-translational modifications after spinal cord injury

- Axonal mRNA localization and local translation in neurodegenerative diseases

- Alzheimer’s disease: a tale of two diseases?