Geochemistry of platinum-group elements in the podiform chromitites and associated peridotites of the Nain ophiolites,Central Iran:Implications for geotectonic setting

Batoul Taghipour ·Somayeh Shabani·Alireza K Somarin

Abstract The Nain ophiolite complex with an extent of>600 km2 is a part of the Central Iranian ophiolite,which is related to the opening and subsequent closure of the Neo-Tethys Ocean.Dunite and serpentinized harzburgite in the Nain area host podiform chromitites that occur as three(eastern Hajhossein,western Hajhossein,and Soheil Pakuh)schlieren-type tabular and aligned massive lenses with various sizes.The most common chromitite ore textures are massive,nodular,disseminated,and banded,ref lecting crystal settling processes.The Cr#[Cr/(Cr+Al)]ranges from 0.43 to 0.81(average 0.63).The Mg#[Mg/(Mg+Fe2+)]varies from 0.25 to 0.78(average 0.62).The Nain ophiolite and hosted chromitite are generally characterized by high Cr#,ref lecting crystallization from a very hot boninite magma in a MORB setting.The high Cr#in the Nain chromititealso indicatesahigh degree of melting(15%-35%)of the depleted peridotite.The average total PGE content in the ophiolitic host rock(harzburgiteand dunite)and chromite are 107 and 221 ppb,respectively.The Nain ophiolite and chromitite have high IPGE/PPGE and negative Pt*(Pt/Pt*=0.6)anomaly,which is a characteristic of high Cr#chromitite.The U-shaped REE pattern of dunite host rock suggests the interaction of depleted mantle peridotite with boninitic melt.Geochemical data suggest that the Nain chromitites arerelated to theboninitic magmaemplacement in asuprasubduction zone.

Keywords Nain chromitite·Platinum group elements·Ushaped REE pattern·Boninitic magma·Supra-subduction zone

1 Introduction

Ophiolites represent a section of the Earth’s oceanic crust and the underlying upper mantle that has been uplifted and emplaced onto the continental crust(e.g.,Do¨nmez et al.2014a,b).The ophiolites in Iran are related to the opening and closure of the Paleo-Tethys and Neo-Tethys oceans.They are part of the Tethyan ophiolite belt of the Middle East,which link the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean Hellenides-Dinarides ophiolites(e.g.,Turkish,Troodos,Greek,and East European)to more easterly Asian ophiolite(e.g.,Pakistani and Tibetan)(Shojaat et al.2003;Ghazi et al.2010).The most outstanding ones in Iran are Central Iranian and Zagros ophiolites.There are two ophiolite occurrences in the western part of Central Iran:Mesozoic ophiolite(e.g.,Nain,Ashin)and Paleozoic ophiolite(e.g.,Anarak,Jandagh)(Torabi 2013).The Nain ophiolite is interpreted to represent either the occurrence of a narrow seaway(like the Red Sea)between the Lut Block and the active margin of the Iranian Block(Sanandaj-Sirjan zone,e.g.,Berberian and King 1981)or an arc basin of the Tethyan subduction system which was active from Upper Triassic to Quaternary(Desmons and Beccaluva 1983;Ghazi et al.2010;Taghipour and Ahmadnejad 2018).Three chromitite deposits(eastern Haj-Hossein,western Haj-Hossein,and Soheil Pakuh)occur in the Nain ophiolite complex.Chromitite masses in the ophiolite sequences provide valuable information about tectonic and petrogenetic processes in the upper mantle(Stow 1994;Torabi 2013).Podiform chromitites in ophiolite sequences mainly occur in the transitional zone,usually up to the Moho or a depth>1 km below it(Auge1987;Nicolas1989;Melcher et al.1997;Zhou et al.1998;Proenza et al.2004;Gervilla et al.2005).The podiform chromitites have been studied extensively since the 1960s(e.g.,Thayer 1964,1969;Dickey 1975;Paktunc and Baysal 1981;Lago et al.1982;Dick and Bullen 1984;Leblanc and Nicolas 1992;1998;Cahit Do¨nmez et al.2014a,b).In some ophiolite complexes,chromium-rich chromitites have PGE mineralization especially Os,Ir,and Ru(Crocket 2002).Such PGEbearing chromitites have been investigated vigorously worldwide(e.g.,Maurel and Maurel 1982;Dick and Bullen 1984;Barnes et al.1985;Nakagawa and Franco 1997;Ballhaus1998;Barnesand Roeder 2001;Kamenetsky et al.2001;Andrews and Brenan 2002;Garrutti 2004;Rollinson 2008;Gonza′les-Jimene′z et al.2011;Ahmed et al.2013;Kiselevas and Zhmodik 2017).

Based on melting temperature,platinum group elements can be divided into two groups:the iridium group(IPGE;melting temperature>2000°C)consists of Os,Ir,and Ru(also known as refractory PGE);and the platinum group(PPGE;melting temperature<2000°C)consists of Rh,Pt,and Pd(Woodland et al.2002;Hatice Kozlu et al.2014).The refractory PGEs cab is mobilized during chromitite alteration(Melcher et al.1997;Proenza et al.1999).

Chromian spinel chemistry and PGE distribution/abundance are signif icant geochemical tools to determine parental melt composition, partial melting, melt-rock interaction,and sulfur saturation of theprimary melts(Dick and Bullen 1984;Barnes et al.1985;Rehka¨mper et al.1997;Ballhaus 1998;Barnes and Roeder 2001;Kamenetsky et al.2001;Naldrett 2010;Derbyshire et al.2013;Kiselevas and Zhmodik 2017).High-Al chromitite[(Cr#<0.60;Cr#is the atomic ratio Cr/(Cr+Al)]and high-Cr chromitite(Cr#>0.60)indicate derivation from MORB-like(mid-ocean ridge basalt)tholeiitic magmas and boninitic compositions,respectively(Zhou and Bai 1994;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014).The composition of chromite is affected by composition of the mantle source and type of melt formed in different tectonic settings,such as MORB,island arc tholeiite(IAT),oceanisland basalt(OIB),and boninite(Arai et al.2011;Zaccarini et al.2011;Do¨nmez et al.2014a,b).Chromitites with high chromium value have higher PGE contents compared to high-Al chromitites(Gonza′lez-Jime′nez et al.2011;Proenza et al.1999;Gervilla et al.2005;Uysal et al.2009a,b a,b;Do¨nmez et al.2014a,b)ref lecting the nature of parental magma(Zhou et al.1998;Uysal et al.2009a,b a,b;Gonza′lez-Jime′nez et al.2011;Zaccarini et al.2011;Do¨nmez et al.2014a,b).

This research uses mineral chemistry of the Nain chromian spinel and distribution of PGEs in the chromitite and host dunite and harzburgite to better understand the genesis of chromitites and possible tectonic setting of the Nain ophiolitic rocks.

2 Geological setting

2.1 General geology

Based on age,there are two groups of ophiolites in Iran(Jannessary et al.2012)(Fig.1).1)Paleozoic ophiolitesare considered to be remnants of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean situated between the Eurasian plate in the north and the Gondwanian plate in the south.They outcrop in the north and northeast of Iran as the Asalem-Shanderman and Mashhad ophiolites:(Sengo¨r 1979;Sto¨cklin 1977;Wensink and Varekamp 1980).2)Mesozoic ophiolites are considered to be remnants of the Neo-Tethys Ocean situated between the Iranian plate in the north and the Arabian plate in the south.This group includes two subgroups(Lensch and Davoudzadeh 1982;Sto¨cklin 1977).I)Outer sub-belt or southern sub-belt(Zagros type)located immediately to the southwest of the Main Zagros Thrust Zone which includes the Kermanshah and Neyriz ophiolites that extend into the Oman ophiolite(Babaie et al.2001,2006;Jannessary 2003;Ricou 1971).The outer sub-belt is interpreted as a remnant of the Neo-Tethys Ocean that was obducted along the main Zagros thrust bounding the southern margin of the Sanandaj-Sirjan zone.II)The inner or northern sub-belt(Central Iranian type),represented by extensive colored me′lange zones,is located around the Central Iranian micro-continent and includes the Sabzevar,Nain-Baft,Esfandagheh,Makran,and Birjand ophiolites(Ahmadipour et al.2003;Alavi-Tehrani 1977;Arvin and Robinson 1994;Delaloye and Desmons 1980;Desmons and Beccaluva 1983;Gansser 1960;Ghasemi et al.2002;Kananian et al.2001;Lensch et al.1977;McCall 1997,Eslami et al.2018).A part of this belt along the northern margin of the south Sanandaj-Sirjan Zone is a remnant of the Paleo-Tethys(Ghasemi and Talbot 2006).The Nain ophiolites are believed to be derived from the Cretaceous oceanic lithosphere which surrounded the CIM block(Central Iranian Micro-continental,i.e.,Lut block)in the south-east of the Eurasia continental plate.Paleomagnetic data indicate that during the Mesozoic,the CIM moved northward,and contemporaneously underwent a counterclockwise rotation of about 130°toward the southern rim of Eurasia(Schmidt and Soffel 1983;Ghazi et al.2011),leading to the development of subduction zones where the oceanic lithosphere was deformed and metamorphosed.

2.2 Nain ophiolite complex

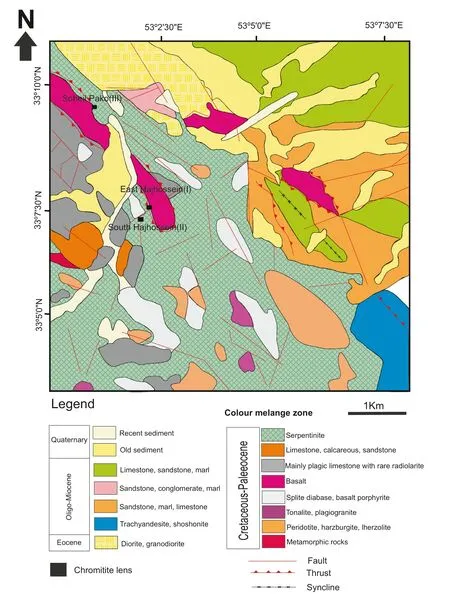

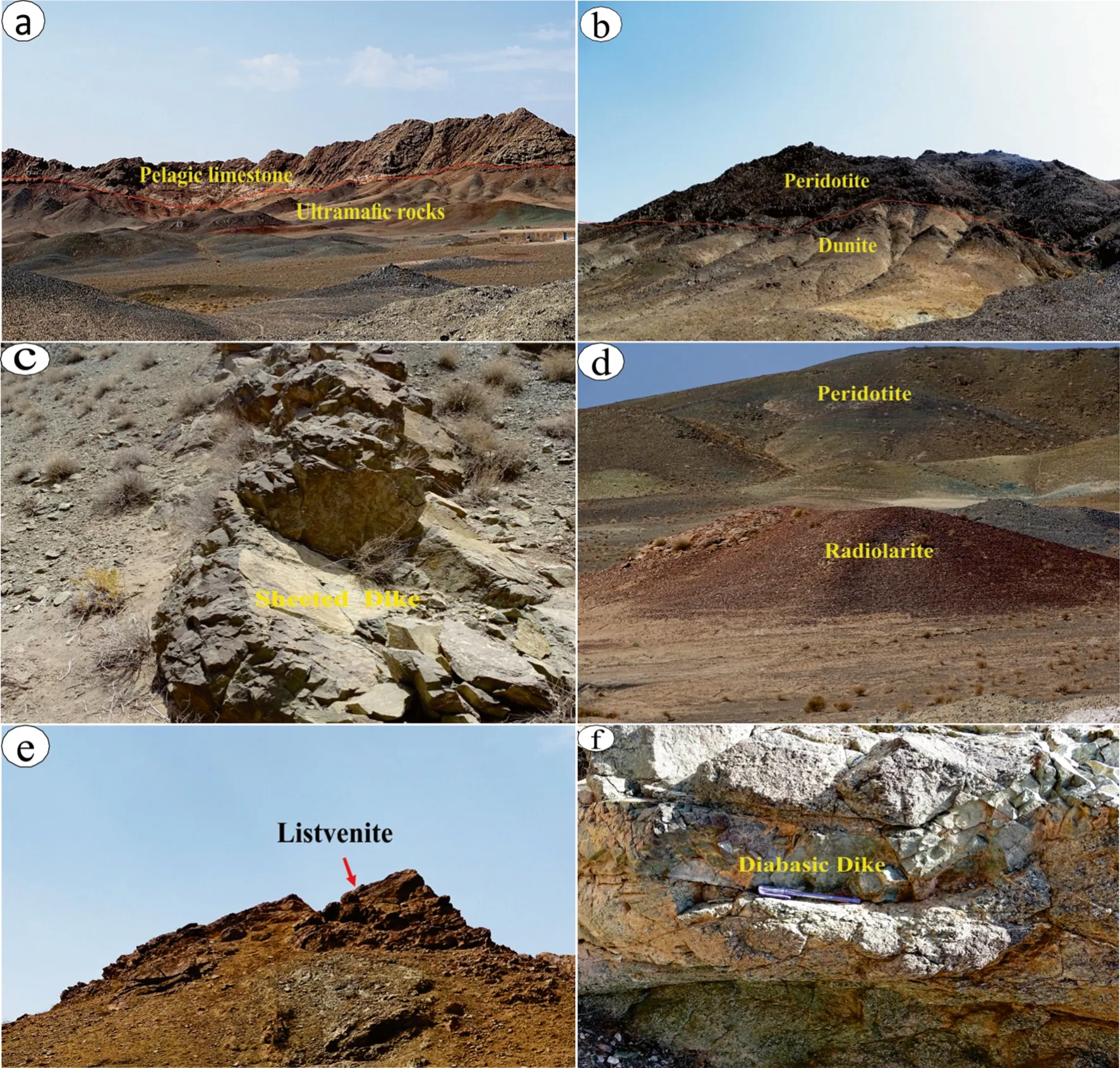

The Nain ophiolite covers an approximately 600 km2wide area,north of the town of Nain,along the Nain-Baft fault zone(Fig.2).Three geological units occur north of the Nain area(Ghazi,2011):(I)the ophiolitebearing colored me′lange unit cropped out with an NNWSSE trending through the central area,(II)the Tertiary volcanic unit associated with small Tertiary dioritic intrusions in the west,and(III)the Tertiary sedimentary unit in the east.The Nain ophiolite,similar to other ophiolitic complexes,includes two stratigraphic sequences(Fig.3a):mantle sequence and crustal sequence(Torabi 2013).The mantle sequence is made up of peridotites that include harzburgite with minor lherzolite and dunite.The peridotites are commonly strongly serpentinized with an increasing degree from lherzolite through harzburgite to dunite(Fig.3b).The shallower rock types include pegmatitic gabbro,dioritic dike,plagiogranite,sheeted dike,and pillow lava.The pyroxenite and websterite associated with wherlite and gabbro norites occur either as dykes or as small pockets in the peridotites(Fig.3c).The main rock units in the Nain area include an Upper Cretaceous ophiolitic complex and overlying younger rocks.The Nain ophiolite consists of a complex of igneous,metamorphic,and sedimentary rocks,pelagic limestone,turbiditic sediments,radiolarite,and chert.The radiolarite reaches several tens of meters in thickness(Fig.3d).The ophiolite sequence is composed of harzburgite and dunite with lesser lherzolite,serpentinite,pyroxenite,gabbro,diorite,plagiogranite,listvenite,and podiform chromitite(Fig.3e).The peridotite makes up 70%of the me′lange in the Nain ophiolite.Three massive and nodular chromitite lenses of the Nain ophiolite(southern Haj-Hossein,eastern Haj-Hossein,and Soheil-Pakuh areas;Fig.2)are hosted by serpentinized dunite and harzburgite.These chromitites are characterized by a massive,dominantly brecciated structure which is mainly comprised of the chromian spinel grains.Chromitite mainly shows brecciated and cataclastic texture due to tectonic activities.Close to the chromitite,relicts of diabasic dike can be found in dunite and harzburgite(Fig.3f).

Fig.2 Geological map of the Nain area(modified after Ghazi 2011)

Fig.3 Field photographsof the rock units of the Nain ophiolite.a Pelagic limestones overlying ultramaf ic rocks with normal contact.b Gradual transition between peridotite and dunite.c Small dykes in peridotites.d Outcrop of radiolarite,e Outcrop of Listvenite.f Diabasic dykes within peridotites

3 Lithology and petrography of the host rock and chromitite units

3.1 Host rock

The Nain chromite-hosted peridotite and maf ic rocks consist of four main geological units:

Lherzolite:it is composed of olivine,orthopyroxene,clinopyroxene,chromian spinel,pargasite,and characterized by porphyritic and granular textures.The orthopyroxene phenocrysts contain exsolution lamellae of clinopyroxene.Their margins show absorption embayment f illed and replaced by olivine.This olivine was probably produced by incongruent melting of orthopyroxene as a result of the melt-peridotite reaction.Chromian spinel is anhedral with a light brown color.

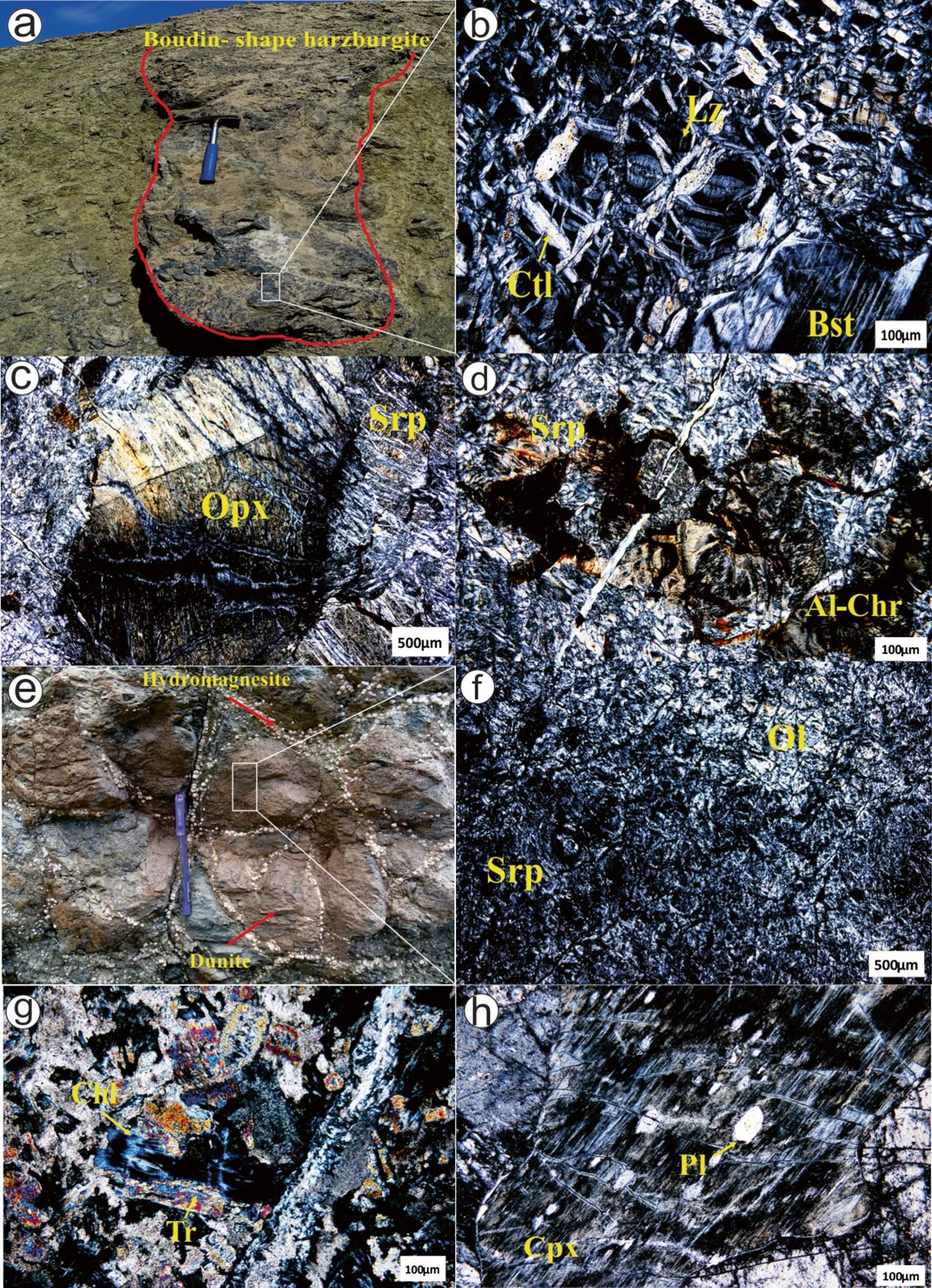

Harzburgite:it isthe most abundant mantle peridotite in the Nain ophiolite and mainly comprised of olivine(60%-50%),orthopyroxene(25%-30%)with minor clinopyroxene(1%-2%),and(1%-2%)chromian spinel.Boudinshape structures occur locally(Fig.4a).Olivine is replaced by serpentine,magnetite,or chlorite assemblage giving the rocks a characteristic mesh texture(Fig.4b).Bastitization of orthopyroxene is common in this rock.Orthopyroxene shows king bands,and wrapped cleavages(Fig.4c).Subhedral to anhedral grains of clinopyroxene occur less than orthopyroxene.There are various degrees of serpentinization mainly along with fractures.Most chromian spinels in some highly serpentinized harzburgite,particularly in high-Al varieties,show secondary ferrian chromite rims.Chromian spinels in harzburgites are typically subhedral to unhedral reddish-brown color(Fig.4d).

Dunite:it is yellow-green in hand specimen and showsa higher degree of serpentinization compared to harzburgite and lherzolite.Dunite is completely serpentinized;olivine is replaced by serpentine and magnetite whereas orthopyroxene is replaced by bastite.Dunite envelopes the podiform chromite lenses,regardless of their shape and size.The main texture of dunite is granular and serpentinization forms a mesh texture.Olivine in the serpentinized dunite is replaced by disseminated and vein-type hydromagnesite(Fig.4e).Dunite is composed of 95%serpentinized olivine,and a minor amount of subhedral dark brown Crspinel,serpentine,tremolite,talc,and chlorite(Fig.4f)Chromian spinel occurs as euhedral crystals and darker color than those in harzburgite and lherzolite.

3.2 Gabbro

xenoliths with various compositions are found in the peridotite.The main xenolith type is gabbro(Ghazi et al.2010).Diabasic-gabbroic dikes contain Cr-spinel,plagioclase,pyroxene,termolite,actinolite,chlorite,and prehnite(Fig.4g).Pegmatite gabbro is mainly composed of large clinopyroxene and plagioclase grains,the occurrence of polysynthetic and poikilitic textures,are common in this rock(Fig.4h).

Fig.4 Field photographs and photomicrographs of the Nain ophiolite.a Various tectonic structures(boudin-shape)in harzburgite and serpentinized peridotites.b Serpentinized harzburgite showing mesh texture with serpentine.c Kink bands in orthopyroxene in harzburgite.d Amoeboid subhedral disseminated chromian spinel in harzburgite.e Serpentinized dunite replaced by disseminated and vein-type hydromagnesite.f Serpentinized olivine.g Termolite,actinolite,chlorite,and prehnite in gabbro.h Ophitic texture.Ol=olivine,Opx=orthopyroxene,Cpx=clinopyroxene,Lz=lizardite,Ctl=chrysotile,Tr=termolite,srp=serpentinite,Bst=bastite

3.3 Chromitite

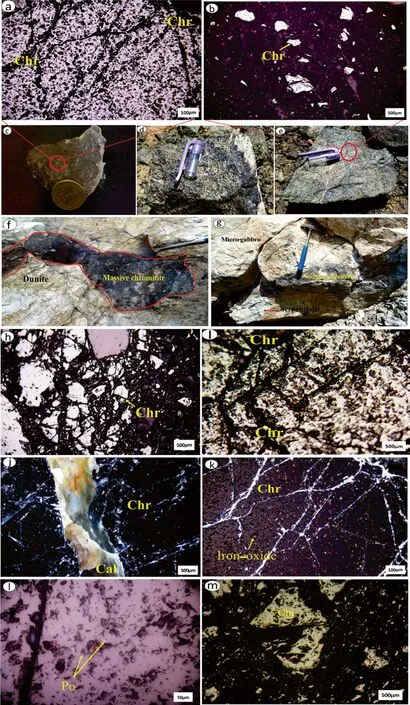

Podiform chromitite of the Nain ophiolites is massive,nodular,and disseminated,and closely associated with dunites and harzburgite(Fig.5a-e).It consists of almost unaltered chromian spinel grains which are locally rimmed by chromian magnetite.Olivine,orthopyroxene,and clinopyroxene are minor minerals accompanied by secondary serpentine and chlorite.Two types of chromitites occur in the harzburgite host rocks:(a)chromitite patches,2-3 cm thick,with sharp contacts,(b)chromitite lenses,2-3 m thick,which are surrounded by 1 m thick dunite envelope(Fig.5f).In the eastern Haj-Hossein deposit,the host rock of chromitite is dunite whereas,in the southern Haj-Hossein deposit,the host rock is micro-gabbro which occurs as diabase dikes(Fig.5g).The effects of tectonic activities and obduction of ophiolite manifest as cohesive cataclastic and pull-apart structures in some chromitite samples(Fig.5h,i).The massive chromitite contains 90%chromian spinel(as coarse-grained crystals up to 2 cm),serpentinized olivine,and secondary chlorite+calcite;calcite occurs locally as veinlets crosscutting chromitite(Fig.5j);iron oxides f ill open spaces in chromite(Fig.5k).Some chromian spinel grains also contain unaltered inclusions of maf ic silicate,and base metal sulf ides(BMS)(Fig.5l).Some of magnetite grains in these rocks are the result of serpentinization of their ultramaf ic host rocks and form corona texture around the serpentinized olivine and pyroxene.Furthermore,chromitecrystalsoccur aseuhedral grains in the serpentinite(Fig.5m).

Fig.5 Field photographs and photomicrographs of the Nain podiform chromitite.a and b Massive and disseminated texture of chromitite.c Massive structure of chromitite.d Nodular structure of chromitite.e Disseminated texture of chromitite f Gradual transition between chromitite and dunite.g Gradual transition between chromitite and microgabbro.h cataclastic structure in chromitite.i massive chromite and pull-apart joint and cracks.g Calcite veinlet crosscutting chromitite matrix.k Accumulation of iron oxides within massive chromitite.l Pyrrhotite inclusion.m Euhedral chromite grains.Chr=Chromitite,Cal=calcite,Po=Pyrrhotite

4 Methodology

Fifty-two representative samples of harzburgite,dunite envelopes,and chromitite were collected during f ieldwork for mineralogical and geochemical investigations.Ten polished and 25 thin sections were studied by ref lected and transmitted microscopy at Shiraz University,Iran.Seven polished-thin sections were examined for chromian spinel in the chromitite,dunite,and harzburgite using a CAMECA SX50 electron microprobe at the Iranian Mineral Processing Research Center(Supplementary Table 1)using 20 kV and 20 nA operating conditions.Analytical errorswere<0.5 wt%and<0.1 wt%for major and minor oxides,respectively.Quantitative (WDS)microprobe analyses were carried out using the crystals TAP(Si,Al),PET(Ti,Ca,and K),RAP,and LiF(Fe,Na).All quantitative major element analyses were calibrated using the following standards:Fe2O3for Fe,wollastonite for Si,MgO for Mg,orthoclase for K,anorthite for Ca and Al,MnTiO3for Ti,and albite for Na.Fifteen samples of the massive chromitite,dunite,and harzburgite were analyzed for major oxides,trace elements,and REEs using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry(ICP-MS)at the Zarazma laboratories,Iran (Supplementary Table 2).Chromitite and dunite trace element and REEcontent were measured following a lithium metaborate/tetrabortate fusion and nitric acid digestion of a 0.2 g sample.Also,a separate 0.5 g split was digested in Aqua Regia and analyzed by ICP-MS for trace elements.The detection limits for traceelementsvaried from 0.1 to 20 ppm and from 0.01 to 0.1 ppm for REEs(Supplementary Table 6).Platinum group elements for twenty bulk chromitite,harzburgite,and dunite samples were analyzed using ICP-MSafter Nisulf ide f ire assay.After pre-concentration,the dissolved sample was analyzed using Perkin-Elmer Sciex ELAN 9000 ICP-MS at Act Lab,Ontario,Canada.Detection limitsare 2 ppb for Os,Ir,Ru,Pt,and Pd,and 1 ppb for Ru(Supplementary Table 3).Two statistical methods including correlation coeff icient and cluster analysis using SPSS(version 22)are utilized to identify the geochemical relationship between elements in the samples.The cluster analysis groups a set of data objects into clusters based on their similarities and differences.

5 Results

5.1 Chromian spinel mineral chemistry

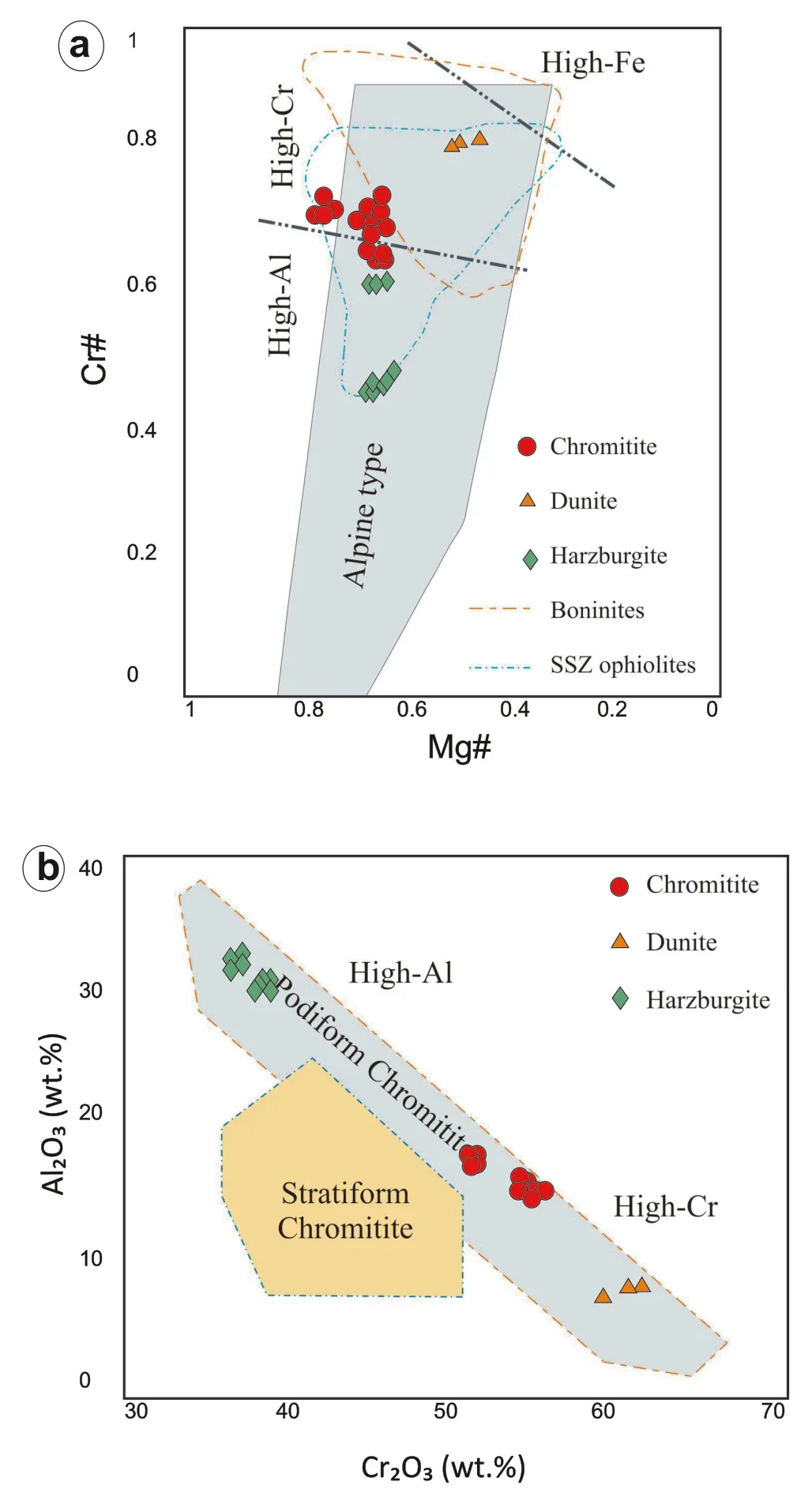

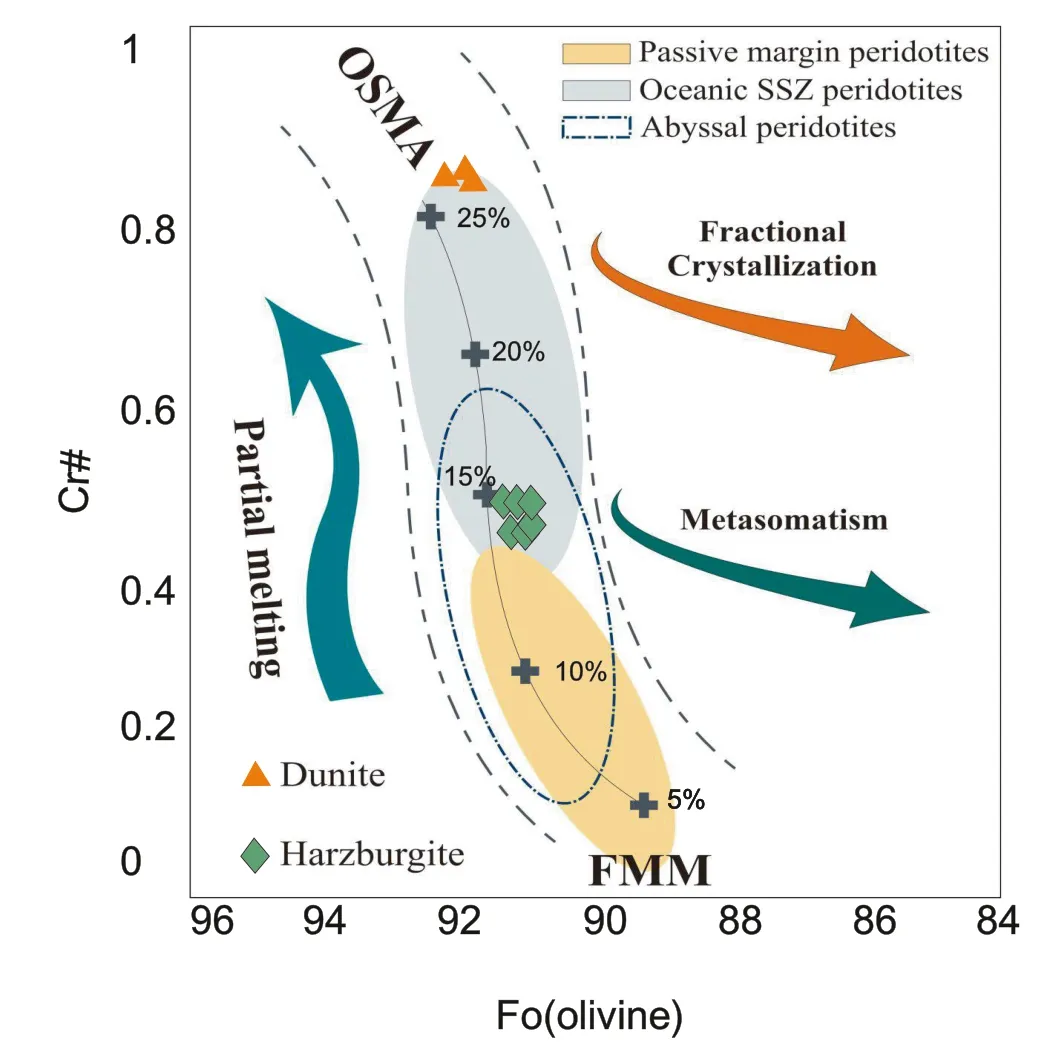

Inthechromititeandhostrock,theCr#(Cr/Cr+Al)and Mg#(Mg/Mg+Fe2)rangefrom 0.43 wt%to 0.81 wt%(average 0.63 wt%)and 0.25 wt%to 0.78 wt%(average 0.62 wt%),respectively.All chromitites are referred to as high-Cr chromitedueto their high Cr#(>0.60wt%).The Cr#versus Mg#diagramshowsthatallthechromititesamplesfall inthesuprasubduction zone(SSZ)f ield(Fig.6a).The Cr2O3and Al2O3content in the Nain ophiolitic host rock and chromitite vary from36.76wt%to60.02wt%,(average49.51wt%),and9.14 wt%to 32.42 wt%(average 19.62 wt%),respectively.The Al2O3versus Cr2O3diagram shows that all the chromitite samples fall in the podiform chromitite f ield(Fig.6b).Chromitite-hosted dunite hasthe highest Cr2O3(60.04 wt%)content with the highest corresponding Cr#(0.8;Supplementary Table 1).Massive chromitite and dunite chromian spinelplotsinthehigh-Cr f ieldwhereasharzburgitechromian spinels plot in the high-Al f ield.The high-Al chromitite(Cr#<0.60)and high-Cr chromitite(Cr#>0.60 wt%)indicatesderivation from MORB-liketholeiitic magmasand boninitic compositions,respectively (Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014);experimental studieshaveshown thatthe high-Cr chromitites are related to the high-Mg tholeiitic or boninitic magmas(Irvine 1977;Fisk 1986;Kelemen et al.1992;Arai 1994;Zhou et al.1996;Gu¨nay and C?olakog?lu 2016).Boninitic magmamay facilitate Cr-spinelprecipitation due to the melt polymineralization caused by intense and widespread reaction with harzburgite(Peck and Keays1990;Gonza′lez-Jime′nez et al.2011;Gu¨nay and C?olakog?lu 2016).

Fig.6 Variation diagrams showing mineral composition of the Nain chromitite.a Binary diagram of Cr#versus Mg#of the chromian spinel in massivechromitite,dunite,and harzburgite.The Alpine-type f ield after Irvine(1967);Supra-subduction zone(SSZ)and boninite after Bridges et al.(1995);high-Cr,high-Al,and high-Fe chromian spinel types are from Zhou and Bai(1992).b Chromian spinel composition of the Nain chromitite.Compositional f ieldsof podiform and stratiform chromitites are after Bonavia et al.(1993)

6 Whole-rock geochemistry

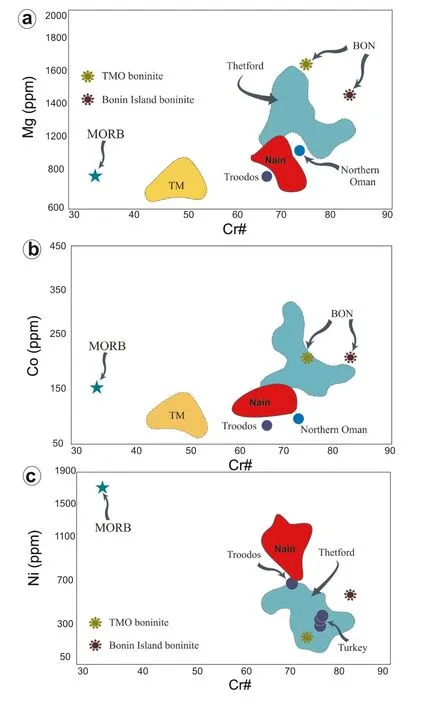

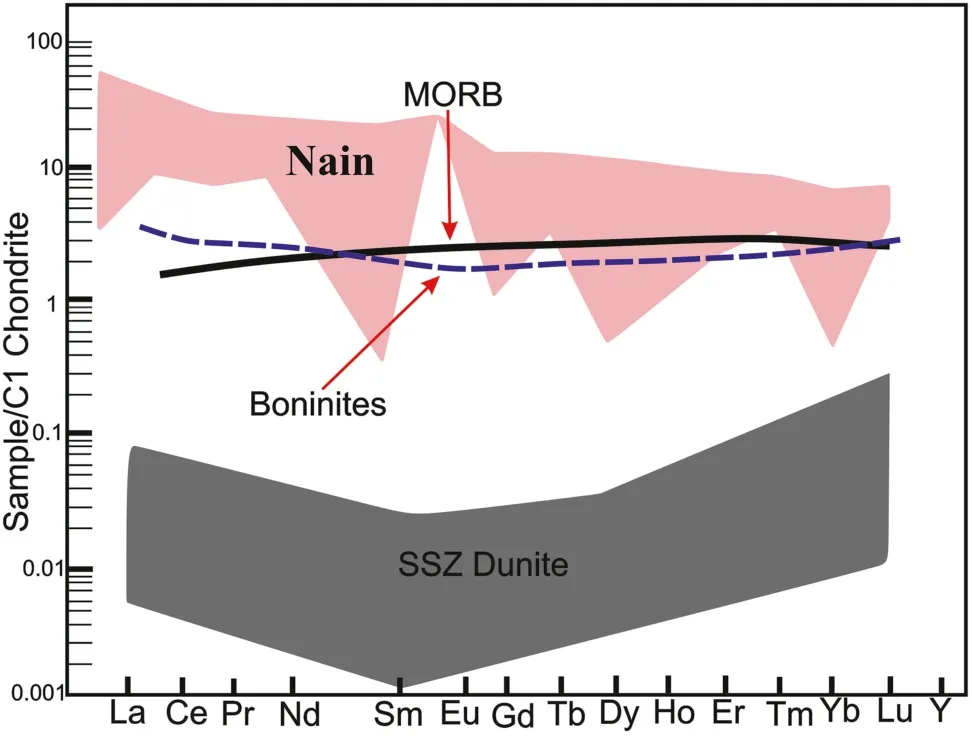

The Mn,Co,and Ni contents of the Nain chromitite ores vary between 770 to 1085 ppm(average 960 ppm),42 to 138 ppm(average 110 ppm),and 290 to 1420 ppm(average 950 ppm),respectively(Supplementary Table 5).The Nain chromitite chemical compositions are close to the Oman chromitite and fall within the chromitites of the Troodos region(Fig.7a,b).Parental magmas of high-Cr chromitites have higher Mn,Co,Ni,and lower V and Zn concentrations than MORB melts;their trace-element patternsaresimilar to those of boninites(Zhou et al.2014).REE content of the Nain chromitite samples are below thedetection limit except for Ceand Yb which vary from 7 to 11 ppm, and 0.4 to 0.5 ppm, respectively(Supplementary Table 4).The∑LREE(light REE)in the peridotitehost rock rangesbetween 3 and 65 ppm,whereas∑HREE(heavy REE)rangesfrom 1 to 28 ppm.The Nain chromitite,dunite,and harzburgite show enrichment in LREE relative to HREE(the HREE were mostly below detection limits)(Fig.8).

Fig.7 Trace element composition of the Nain chromitite.a Cr#versus Ni.b Co#versus Cr.c Cr#versus Mn.Trace element contents of the Nain samples are similar to those in chromitites that originated from the boninitic magma.Thetford chromitite data from Page and Barnes(2009).Boninite and mid-ocean ridge basalt(MORB)data from Barnes and Roeder(2001).The Troodos and northern Oman chromitite data are from Paktunc and Cabri(1995)and Arai and Yurimoto(1994),respectively

Fig.8 Comparison of the REE patterns of the Nain dunite,MORB,and boninite with supra-subduction zone(SSZ)dunite(data from Caran et al.2010)

7 BMSinclusions in chromititeand host peridotite

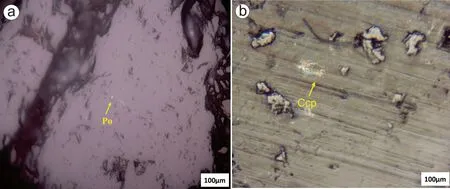

Base metal sulf ide(BMS)inclusions of pyrite,pyrrhohtite,as well asmagnetite inclusions,were identified in the Nain chromitite and host peridotite rocks(Fig.9a,b).Most pyrite grains are subhedral to euhedral and occur either as inclusions or more commonly as accessory minerals within the serpentine matrix f illing the spaces between chromite grains in both high-Cr and high-Al chromitites.The inclusions may represent droplets of trapped liquid from the contaminated sialic melt which may suggest that these inclusionsformed asaresult of chemical reactionsbetween the anhydrous silicates in the chromite-precipitating magma(olivine and pyroxene),trapped volatile-rich silicate melt,and f luid inside the inclusions(Ismail et al.2014).

Fig.9 Sulf ide in the Nain chromitite.a Pyrrhotite(PPL,ref lected light).b Chalcopyrite(backscattered image).Po=Pyrrhotite,Ccp=chalcopyrite

8 Whole-rock PGE geochemistry

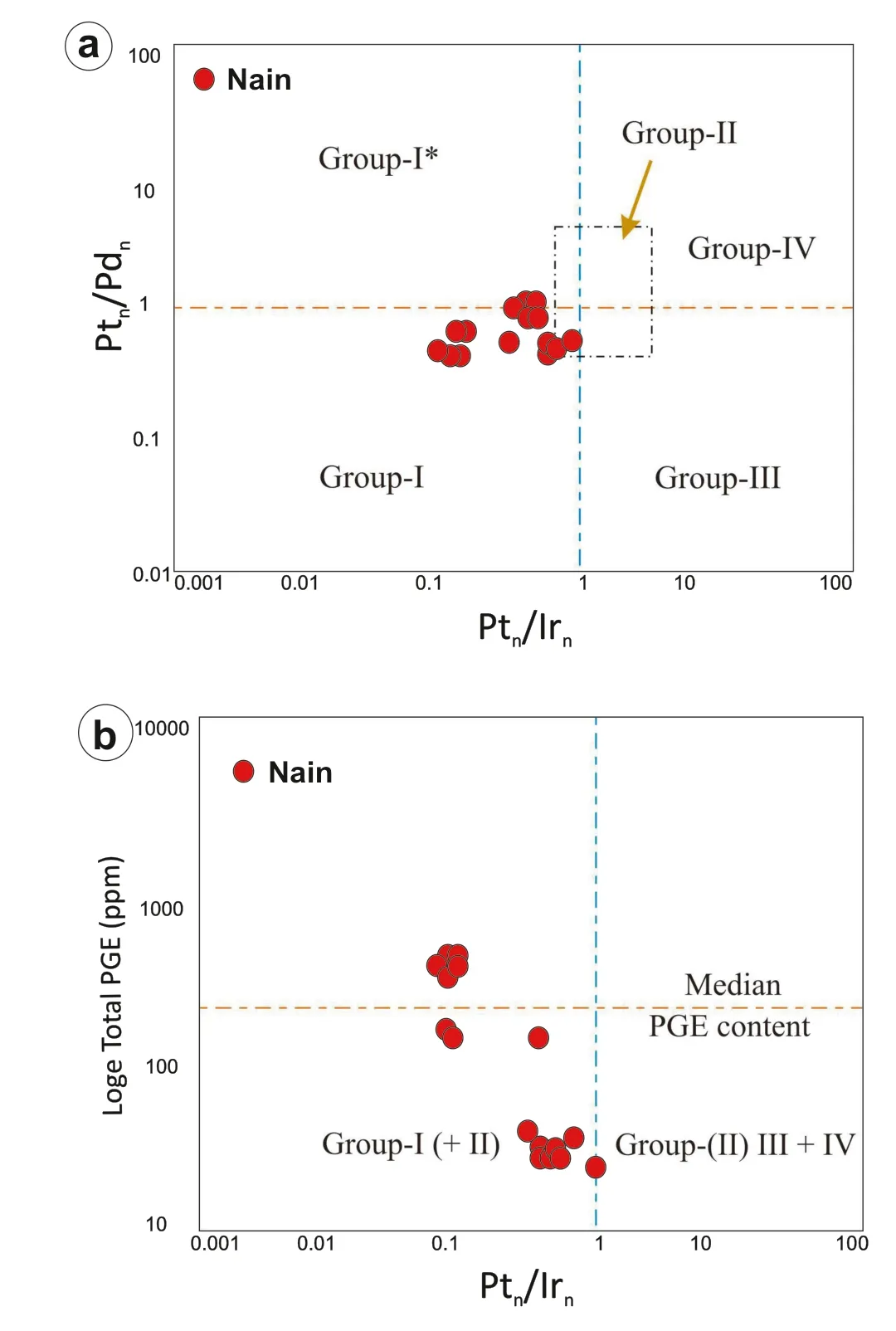

Total PGE content in the analyzed chromitites varies from 24 to 283 ppb(average 107 ppb).Chondrite-normalized PGE pattern of the chromitites is characterized by enrichment in IPGE(Os,Ir,and Ru)relative to PPGE(Rh,Pt,and Pd)(Fig.10a,b)with positive Ru and negative Pt anomalies,anegativetrend from Ir to Pd group metals,and a very low PPGE/IPGE ratios(mean Pdn/Irn ratio of 0.1).Comparison of the PGE spider diagrams of chromitite,dunite,and harzburgite indicates that chromitite samples have more IPGE than dunite and harzburgite.Dunite and harzburgite PGE spider diagrams show a similar pattern to that in chromitite.Burghath et al.(2002)classified ophiolitic chromititesinto four groupsbased on the Pt/Ir and Pt/Pd ratios(Fig.11a,b).Group-I,called‘‘normal ophiolite type’’,is characterized by negative slopes from Os to Pt in the normalized diagrams,Ptn/Irn<0.9,and total PGE content of about 200 ppb.Group-II,the‘‘diverging ophiolite type’’,has higher proportions of base metal sulf ides and may carry up to 11 ppm PGE.The Ptn/Irnratio varies between 0.9 and 4.6,and the PGE pattern is generally f lat with PPGE/IPGE~1.Group-III is characterized by high Pd,abundant base metal sulf ides,Ptn/Irn>1,and Ptn/Pdnmostly<1.Group-IV,the‘‘Pt dominated sulf ide-poor ophiolite type’’is restricted to late-stage chromitites in ultramaf ic cumulates close to the crust-mantle transition zone.The Nain chromitites contain up to 282 ppb total PGE;irrespective of their PGE abundances,they display a systematic enrichment in IPGE relative to PPGE with a steep negative slope in the PGE spider diagrams,and very low PPGE/IPGE ratios(mean Pdn/Irnratio of 0.1).These features are typical of ophiolitic podiform chromitites worldwide(e.g.,Ahmed and Arai 2002;Bu¨chl et al.2004;Gonza′lez-Jime′nez et al.2011;Leblanc and Nicolas 1992;Tsoupas and Economou-Eliopoulos 2008;Zhou et al 2005;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014).

Fig.10 a Chondrite-normalized PGEpattern of the Nain podiform chromitite.The f ieldsof worldwidechromitite(Economu-Eliopoulos,1996;Garuti et al.,2005;Melcher et al.,1997;Proenza et al.1999;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2016;Economou-Eliopoulos et al.2017),Luobusa ultra-high pressure(UHP)(Zhou et al.1996),N-Shitna(Ismail et al.2014);and Elekdag(Donmez et al.2014)are for comparison.b Chondrite normalized PGE for the Nain chromitite,dunite,and harzburgite.Chondrite values are from Naldrett and Duke(1980)

Fig.11 a Mantle-normalized ratio of Pt/Ir versus Pt/Pd for the Nain chromitite,dunite,and harzburgite.b Mantle-normalized Pt/Ir versus total PGEcontent.Group def inition according to Burgath et al.(2002)

9 Discussion

9.1 Parental melt composition of chromitite and melt reaction

Chromite composition is a signif icant geochemical tool to determine magma genesis in various geodynamic environments as the geochemical composition of chromite depends on its parental melt(Dick and Bullen 1984;Zhou et al.1998;Kamenetsky et al.2001;Araiet al.2006,2011;Garutiet al.2007;Rollinson 2008;Gonza′lez-Jime′nez et al.2009,2011;Pal 2011;Gu¨nay and C?olakog?lu 2016).The podiform chromite origin has long been a matter of debate(Zhou and Robinson 1997;Ballhaus 1998;Melcher et al.1999;Buchl et al.2004;Rollinson and Adetunji 2013,Zhou et al.2014).Chromitites form during melt-rock reaction and/or melt-melt interaction in the supra-subduction zone.The melts that formed the chromitites were not in equilibrium with the host peridotites(Zhou et al.1998;Melcher et al.1999;Kamenetsky et al.2001;Uysal et al.2005,2009a,2009b;Gonza′lez-Jime′nez et al.2011;Zaccarini et al.2011;Gu¨nay and C?olakog?lu 2016).The podiform chromitites using as a good indicator of peridotite-melt reactions in the upper mantle(e.g.,Arai 1997,2013).Podiform chromititesarecommonly hosted in residual mantle peridotites,characterized by small pods,veins,and envelopes of dunite in the upper mantle-Moho transition zone(Yang et al.2015,Arai et al.2010,2014).Dunite envelopes,chromitites ref lect a genetic link between peridotite host rock and chromitite unites,as well as their contemporaneous formation(Arai and Yurimoto 1994;Zhou and Robinson 1994;Zhou et al.1996;Arai 1997;Gervilla et al.2005;Page′and Barnes 2009;Gonzalez-Jimenez et al.2013).Dunite envelopes of chromite deposits are commonly considered as evidence for meltrock interaction(Zhou et al.2014).These envelopes in the residual harzburgites or lherzolites generally ref lect meltrock interaction which causes orthopyroxene dissolution and olivine precipitation(Kelemen et al.1992;Edwards and Malpas 1996;Zhou et al.1996;Suhr et al.1998).The reaction of olivine-saturated magma with the mantle peridotite host rock removed pyroxene and left dunite envelope(Kelemen et al.1992,1997;Zhou et al.1994,1996;Kelemen and Dick 1995).The reaction between peridotite and melt is crucial in forming a relatively silica-rich melt.Therefore,podiform chromitites form in settings where peridotite-melt reactions readily occur.Major elements of chromian spinel in the Nain ophiolite suggest that the mantle peridotites originally had a MORB aff inity but that the podiform chromitites formed from hydrous boninitic magmas in the SSZ environment(Figs.12,16a).Transitional boundaries between chromitite, dunite, and harzburgite provide textural evidence for melt-rock interaction(Fig.5f,g).Based on the following reaction,the interaction of magmas with mantle peridotites converts pyroxenes to olivine and adds SiO2to the magmas(Zhou 2014):

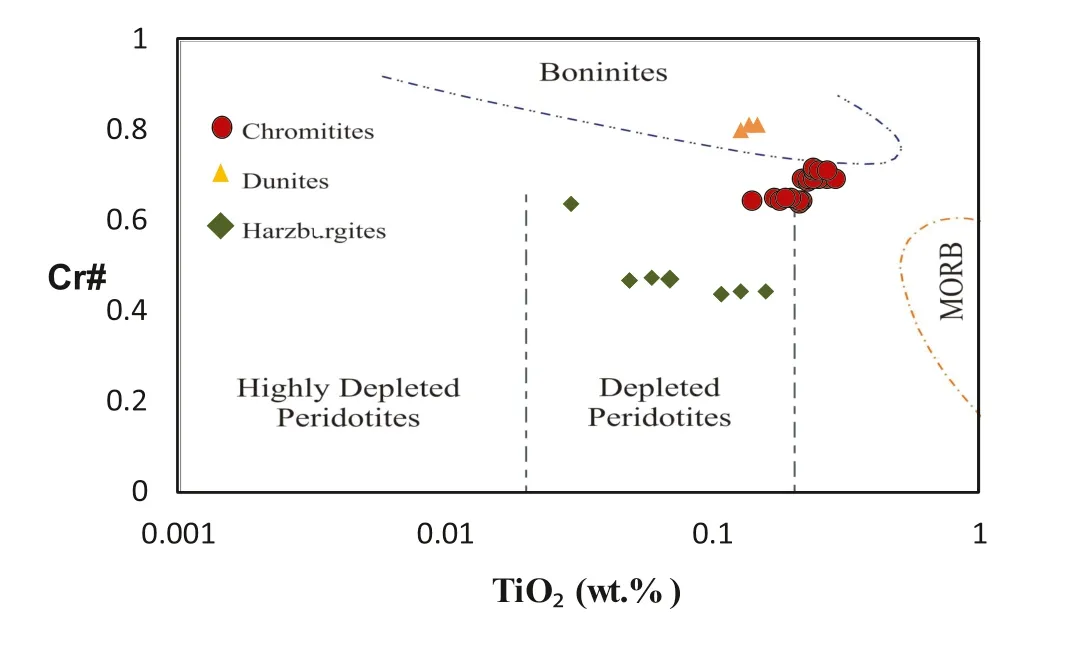

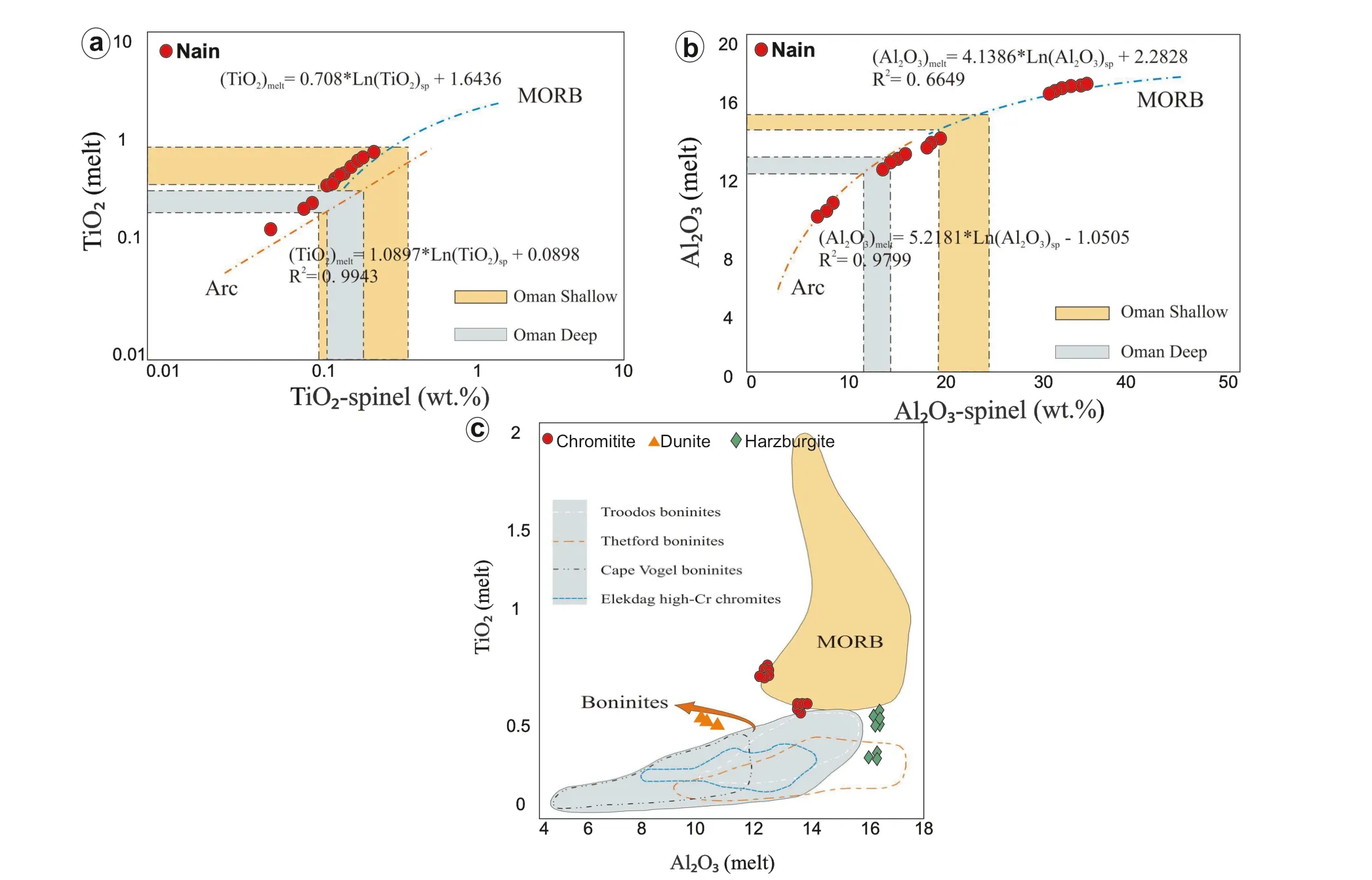

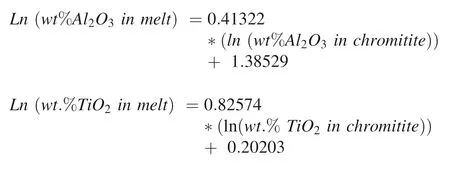

The addition of SiO2may decrease Cr solubility,which causes chromite precipitation(Zhou et al.1994;Zhou and Robinson 1994).The chromian spinels chemistry,particularly their FeO,MgO,Al2O3,and TiO2content,is an important petrogenetic indicator of parental melt composition(Maurel and Maurel 1982;Dick and Bullen 1984;Melcher et al.1997;Zhou et al.1998;Kamenetsky et al.2001;Rollinson 2008;Gonza′lez-Jime′nez et al.2011;Kiselevasand Zhmodik 2017).The Cr#variesfrom 0.64 wt%to 0.72 wt%in chromitite,and from 0.79 wt%to 0.81 wt%in dunite,and from 0.43 wt%to 0.81 wt%in harzburgite at Nain;TiO2content of Cr-spinel varies from 0.2 wt%to 0.3 wt%.The Cr#versus TiO2diagram showsthe studied samplesplot in thedepleted peridotitesand trend totheboninite f ield(Fig.12).Furthermore,TiO2and Al2O3of melt versus TiO2and Al2O3of spinel can also help to determineparental meltcomposition(Fig.13a-c).The Nainsamples,compared to the Oman ophiolite,show an aff inity to the MORB.The TiO2and Al2O3values of chromian spinel correlate with those of the parental melt.On the Al2O3-melt versus TiO2-meltdiscriminationdiagram(Fig.13c),the Nainchromitites plot in the boninite f ield near Thetford and Troodos boninites.These results show that the parental melt of the Nain chromitites was similar to boninite with some aff inity to MORB.It ispossible that the boninitic melt was in equilibrium with MORB-like melt(Ahmed and Arai 2002;Miura et al.2012).

Fig.12 Cr#versus TiO2 showing that the high-Cr chromitites have a boninitic aff inity in an arc setting and the high-Al chromitites formed in a depleted mantle source trending towards MORB(boundaries and f ields after Jan and Windley 1990)

Fig.13 Calculated Al2O3 and TiO2 values for the Nain parental melt.a TiO2-melt(wt%)versus TiO2-spinel(wt%)diagram.b Al2O3-melt(wt%)versus Al2O3-spinel(wt%)diagram.The regression lines for arc magma and MORB are from Kamenetsky et al.(2001)and Rollinson(2008),respectively.Thef ield of shallow and deep Wadi Rajmichromititesin Oman isfrom Rollinson(2008).The rangeof chromian spinel and the calculated melt compositions for the Nain chromitites are shown as the gray f ield.c TiO2-melt(wt%)versus Al2O3-melt(wt%)diagram showing the Nain samples plot in the boninitic f ield(after Jenner 1981;Walker and Cameron 1983;Kamenetsky et al.2002)similar to the Thetford(Pages and Barnes 2009),Troodos(Cameron,1985;Flower and Levine,1987),MORB(Shibata et al.1979;Le Roex et al.1987;Presnall and Hoover 1987).Elekdag(Donmez et al.2014)

Harzburgite is the residue of f irst-stage partial melting(20%partial melting)of a fertile lherzolitic source(Bonatti and Michael.1989;Kostopoulos 1991;Gu¨nay and C?olakog?lu 2016).The MORB-like melt is produced in the f irst stage whereas boninitic melt is generated in the second stage(Caran et al.2010;Rajabzadeh et al.2013).Interaction of melt with harzburgite and lherzolite,and removal of Cr-rich orthopyroxene from harzburgite produce more Cr-rich melt and form dunite envelopes around the chromitite bodies(e.g.Kelemen et al.1992;Kubo 2002;Zhou et al.1996,2005).

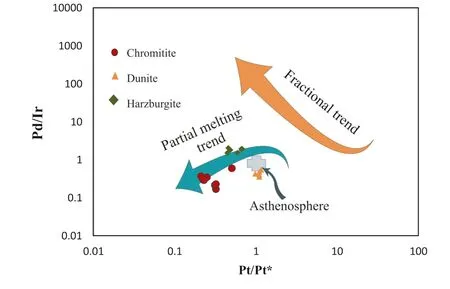

10 Partial melting and PGE fractionation from Sundersaturated boninitic magma

Three important factors that control PGE concentration in igneous rocks are magmatic fractionation,partial melting,and hydrothermal alteration processes(e.g.Barnes et al.1985;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014).A combined process of partial melting and melt/rock interaction in the mantle enriches PGE and Cr in the melt(e.g.Zhou et al.1998;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014).The PGEcan be classified into two groups:(1)Ir and 0 s(IPGE)which are compatible elements,commonly form alloy and reside in a residual mantle,and(2)Pd and Pt(PPGE)which are incompatible elements and preferentially enter the silicate melt during melting(Mondal et al.2019).Differentiation between IPGE and PPGE due to the partial melting,causing a negatively-sloped primitive mantle normalized PGE pattern(Pd/Ir<1).The reaction of the mantle peridotites with S-undersaturated boninitic melt would remove sulf idesand formed dunite relatively enriched in Os,Ir,and Ru,but depleted in Pt and Pd,suggesting sulf ide scarcity,depletion of PPGE,and enrichment of IPGE(particularly Ru)at Nain ophiolite.The high concentration of PGE in high-Cr chromite is due to the critical partial melting(20%-25%)of the mantle(Prichard et al.2008;Kiselevas and Zhmodik 2017).The PGE abundance and Cr-spinel chemistry are useful indicators of the degree of partial melting and sulfur saturation in the primary melt(Nakagawaand Franco 1997;Kiselevasand Zhmodik 2017).It is shown that several compositional parameters(e.g.Cr#of spinel,Fo content of olivine)are signif icant geochemical tools to ref lect the degree of peridotite depletion by melt extraction(e.g.Dick and Bullen 1984;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014).Based on the Cr#versus Fo diagram,the degree of partial melting was 15%in the harzburgite and 25%in dunite samples at Nain(Fig.14).The Pd/Ir content is an important indicator of PGE fractionation(Naldrett et al.1979;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014).Chromititesamplesin the Nain complex have awide range of Pd/Ir values(0.18-1.94,with an average of 0.80)which ref lect variations in the amount of partial melting rather than magmatic fractionation.Furthermore,there is an enrichment of some refractory elements such as Ni,Co,Cr,and PGE especially IPGE which is likely due to the high degree of partial melting(Pearce et al.1992;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014).Basaltic melts that form beneath spreading centers(i.e.,mid-ocean ridges or back-arc basins)are generated by lower degrees of partial melting,usually,lessthan 20%,which isnot suff icient to remove all mantle sulf ide,and thusproduce melts with very low levels of PGE(Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2014).High degrees of partial melting resulted in high Cr#and low Ti and PGE content in the Nain chromitite.The Nain data in the Pd/Ir versus Pt/Pt*[=PtN/(RhN*PdN)1/2]diagram show partial melting trend rather than fractionation(Fig.15).These data suggest that partial melting formed the Nain chromitite,and Ir-group elements crystallized in the primary phases while Pd group elements remained in the residual melt.A high degree of partial melting of the mantle,along with the percolating f luid-rich melt,was required to concentrate an appreciable amount of refractory PGE,especially IPGE,with a very low Pd/Ir ratio in the Nain area.

Fig.14 Chemical variation of Cr#versus Fo content of olivine-Cr spinel pair in the Nain harzburgite and dunite.Olivine-spinel mantle array(OSMA),FMM=fertile MORB-type mantle partial melting,and other trends are from Arai(1994)

Fig.15 The plot of the platinum anomaly(Pt/Pt*)versus Pd/Ir in the Nain chromitite and peridotite indicating a partial melting trend.Fractional and partial melting trendsarefrom Grautiet al.(1997).The Pt anomaly is calculated as Pt/Pt*=(Pt/8.3)/√[(Rh/1.6)×(Pd/4.4)

10.1 Implications for tectonic setting

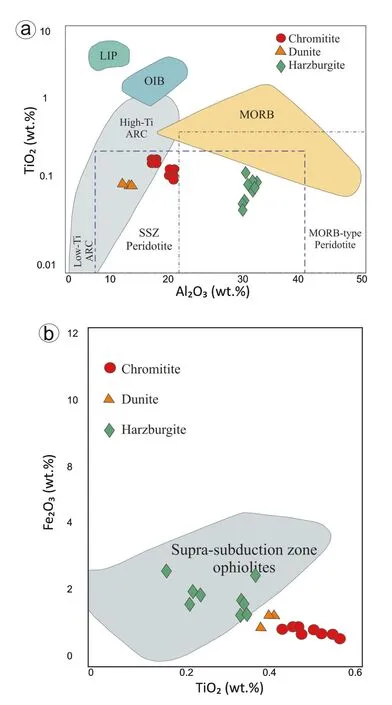

Chemistry of chromian spinel is an important tool that can be used to constrain parental magma and tectonic setting of host-rocks(Dick and Bullen 1984;Kamenetsky et al.2001;Arai et al.2011;Gu¨nay and C?olakog?lu 2016).Also,TiO2value in chromitite and host rock is a signif icant tool to determinetectonic setting(Bonaviaet al.1993;Najafzadeh 2014).Chromian spinel composition of mantle-hosted chromitites can be affected by I)different mechanism of ophiolite formation for various durations(Melcher et al.1997;Zhou and Robinson 1997;Zhou et al.1998;Uysal et al.2009b);II)progressive fractionation of Cr-rich melt in the fore-arc setting shallower and deeper processes below the MOHO transition zone(Rollinson 2008);IV)different temporal and/or spatial magmatism in a back-arc setting(Gonza′lez-Jime′nez et al.2011;Gu¨nay and C?olakog?lu 2016).The boninitic magma composition suggests that the Nain ophiolitic complex originated in a suprasubduction zone setting.It is assumed that boninites were originated from the strongly refractory mantle,which was metasomatized by Ba-and Sr-rich hydrous f luids released from the subducting slab(e.g.,Orberger et al.1995;Ghazi et al.2011).

Two controversial models have been proposed for the tectonic setting of the Central Iran ophiolites(e.g.Shafaii Moghadam and Stern 2011a,b);I)inner and outer Zagros ophiolitebeltsareremnantsof two distinct Late Cretaceous oceanic basins,and II)they formed in a single disrupted oceanic basin.Age similarity of inner and outer belt ophiolites suggests that these ophiolitic complexes formed in the same fore-arc-supra-subduction tectonic setting,which were subsequently attached to the southern margin of Eurasia during a subduction initiation event(Shafaii Moghadam and Stern 2011a,b).Based on the geochemical characteristics of the basaltic rocks and mineral chemistry,the Nain ophiolitic complex is likely formed in a back-arc basin,during slow subduction that changed progressively from arc-like to depleted MORB-like composition.The high Cr#(>0.6)and low TiO2(<0.3 wt%)in chromitite spinel possibly conf irm arc setting(Arai et al.,2006),however,the oceanic crust rocks(MORB and ultramaf ic rocks)have lower Cr#(<0.60)than arc spinel(Dick and Bullen 1984;Niu and Heikinian 1997;Kamenetsky et al.2001;Arai et al.2006,2011;Gu¨nay and C?olakog?lu 2016).Titanium oxide and Al2O3contents of chromian spinel are signif icant geochemical factors in determining different tectonic settings.The TiO2(melt)and Al2O3(melt)values can be calculated from the following equations(Kamenetsky et al.2001):

The TiO2(melt)values vary from 0.03 to 0.29 wt%(average 0.17 wt%)in chromitite samples and Al2O2(melt)values range from 9.97 wt%to 16.72 wt%(average 13.46 wt%).Based on these values,chromian spinel compositions of the Nain chromitites and peridotites plot in the arc and supra-subduction zone f ields(Fig.16a).The island-arc and back-arc settings are the most widely-accepted settings for the formation of podiform chromitites(e.g.Rollinson 2008;Zhou et al.1998;Najafzadeh and Ahmadipour 2016).The high Cr#values and low TiO2and Al2O2content of the Nain high-Cr chromitites suggest that these chromitites were likely formed in the mantle beneath a fore-arc setting related to a supra-subduction zone.In addition,TiO2versus Fe2O3diagram shows that only harzburgite samples plot within the f ield of supra-subduction zone ophiolites(Fig.16b).

Fig.16 Tectonic discrimination diagrams for the Nain chromitite a)Spinel- Al2O2 versus spinel-TiO2 distribution diagram (after Kamenetsky et al.2001).Compared with compositional f ields of spinels from different types of basalts,mid-ocean ridge basalts(MORB),ocean island basalts(OIB),the f ields of the large igneous province(LIP),Island Arc and mantle peridotite in SSZ(supra subduction zone),and MORsettings.b TiO2 versus Fe2O3 of the Nain chromian spinel(after Bridges et al.1995)

10.1.1 PGE exploration indexes

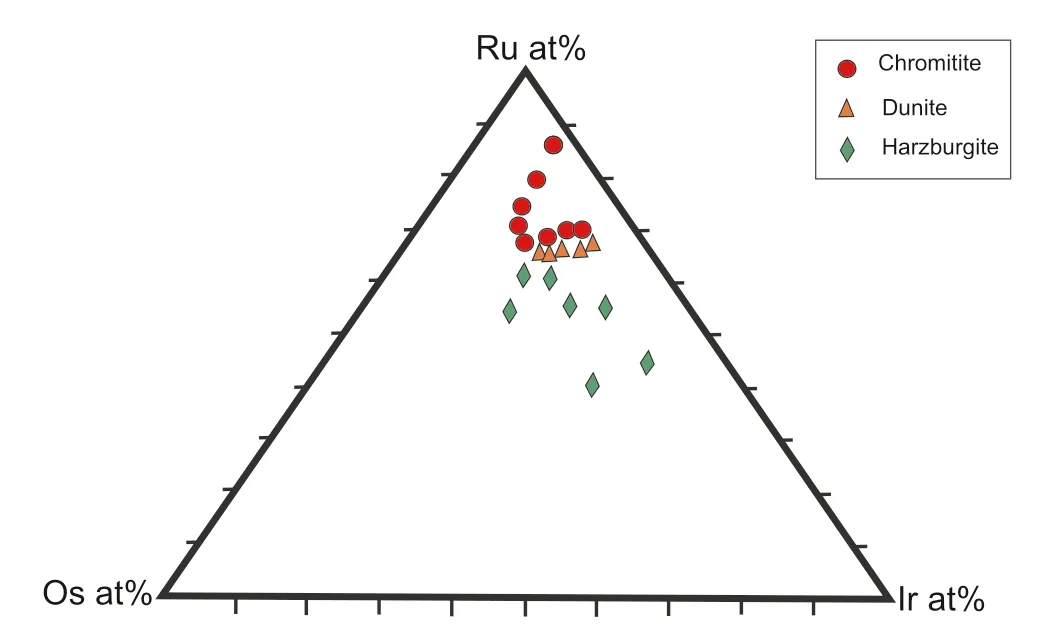

Metal ratio plots of Pd/Ir versus Ni/Cu,and Ni/Pd versus Cu/Ir(Fig.17a,b)are useful tools in determining fractionation during partial melting of the upper mantle.Three different processeslead to the fractionation of PGENi,and Cu in sulf ide ores:(a)partial melting of parental rock,(b)higher concentration of PGEcompared to Cu and Ni in the sulf ide-rich melt,and(c)dissolution of relict sulf ide by S-undersaturated melt and increase of PGE relative to Cu and Ni(Hamlyn and Keays 1986).Fractionation in the sulf ide-rich melt can cause an increase in Pd/Ir and Cu/Ir ratios and a decrease in Ni/Cu and Ni/Pd ratios(Barnes et al.1998).The high content of PGE,especially IPGE content in the chromitites,may be attributed to the second stage of melting and formation of PGE-saturated melt(Hamlyn and Keays 1986;Kiselevas and Zhmodik 2017).Mineralsof refractory PGEsolid solutionsin the Os-Ir-Ru system are usually associated with Cr-rich chrome-spinel,forming intergrowths or inclusions to ref lect mantle paragenesis(Bird and Bassett 1980;Distler et al.1986).The Nain chromitites are relatively enriched in Ir and Ru(Fig.18).Compared to other chromitites in the world,the Nain chromite shows a wide range and have higher total PGE and Pd/Ir ratios and lower average PGE elements(Supplementary Table 6).

Fig.17 Metal ratio diagrams of Pd/Ir versus Ni/Cu and Ni/Pd versus Cu/Ir from Nain compared to Cu-sulf ide ores from the Curaca Valley,Brazil(Maier,unpubl.data),and compositional f ields of ores from Insizwa(data from Lightfoot et al.1984),Levack West(Sudbury Complex,data from Hoffman et al.1979),Lorraine Mine(Abitibi subprovince,data from Barnes et al.1993),and Rathbun Lake(Ontario,data from Rowell and Edgar 1986)

Fig.18 Compositional variation of PGE minerals in the Os-Ir-Ru system

10.1.2 Statistical analyses

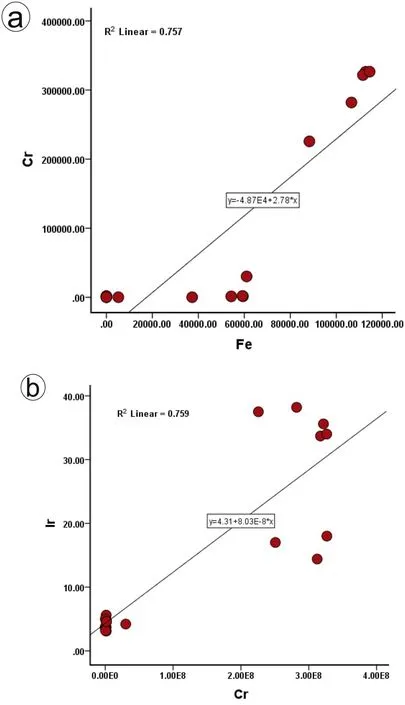

Positive Fe-Cr correlation (Supplementary Table 7;Fig.19a)represents possible Fe3+substation for Cr.The positive correlation between Cr and Ir(Supplementary Table 8;Fig.19b)ref lects an accumulation of IPGE in chromitite.There is a negative correlation between Ni and Pt,Ru,Rh,Pt.

Fig.19 a Scatter plot of Cr versus Fe.b Scatter plot of Ir versus Cr

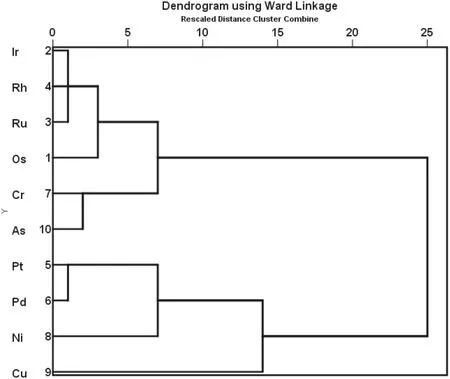

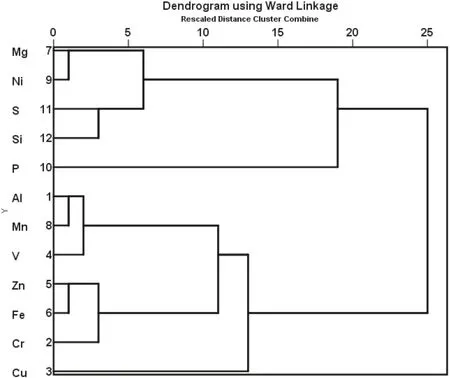

On the cluster analysis plot(Fig.20),Cr,Fe,Zn,and Cu arein thesamegroup and show positivecorrelations.These elements are associated with PGE mineralization.In the cluster diagram for PGE elements,the elements are classified into two general groups,with their subsets.One group contains Cu,Pt,and Pd,and theother group contains Ir,Rh,Ru,Os,and Cr.These ref lect a positive correlation between PPGE(Pt,Pd)and Cu aswell as IPGE(Os,Ru,Ir)and Cr in the Nain chromite deposit(Fig.21).

Fig.20 Clustering for major elements

Fig.21 Clustering for PGE and trace elements

11 Conclusions

The Nain ophiolite and podiform chromitite are characterized by high Cr#which were crystallized from melt originated from 15%-35%partial melting and boninite magma.The calculated composition for the parental melt associated with chromitites is boninitic for the high-Cr chromitites,and boninitic to MORB-like for the high-Al chromitites.A high degree of partial melting in the mantle was required to concentrate an appreciable amount of refractory PGE,especially IPGE.The average total PGEin the ophiolite host rock(harzburgite and dunite)and chromitie are 30.5 and 212.0 ppb,respectively.The Nain ophiolite and chromitite are characterized by high IPGE/PPGE and a negative anomaly of Pt*(Pt/Pt*=0.6),which are characteristics of the high Cr#chromitite.The mineral and bulk PGEgeochemistry for the chromititesin the Nain ophiolite suggests that the boninitic melt formed the high-Cr chromitites at depths in the mantle during melt-rock reaction in a fore-arc tectonic setting.Differentiated melt formed the high-Al chromitites as a result of processes at shallow depth in the upper mantle during melt-rock reaction and/or melt-melt interactions.The Nain podiform chromitites are surrounded by dunite envelopes which ref lect a genetic link between peridotite host rock and chromitite unites.The interaction of magmas with mantle peridotites converted pyroxenes to olivine and added SiO2to the magmas,which caused chromite precipitation.

AcknowledgementThe authors would like to thank the Research committee of Shiraz University and the Iranian Mineral Processing Research Center(IMPRC)that provided f inancial support for this study.We are grateful to Professors Maria Economou-Eliopoulos and Dave Lentz for their valuable and constructive comments that improved the manuscript.Many thanks to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments.A special thanks are extended to editors for handling the manuscript.

Declaration

Conf lict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conf lict of interest.

- Acta Geochimica的其它文章

- Correction to:Variations of methane stable isotopic values from an Alpine peatland on the eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau

- Bicarbonate use and carbon dioxide concentrating mechanisms in photosynthetic organisms

- The possible source of uranium mineralization in felsic volcanic rocks,Eastern Desert,Egypt of the Arabian-Nubian Shield:Constraints from whole-rock geochemistry and spectrometric prospection

- Dissolved organic carbon concentration and its seasonal variation in the Huguangyan Maar Lake of Southern China

- Geochemistry and provenance of the lower-middle pliocene cheleken formation,Iran

- Geochemistry,geochronology,and zircon Hf isotopic compositions of felsite porphyry in Xiangshan uranium oref ield and its geological implication