A Sociocultural Perspective of Teacher Language Use and Learner Participation in Chinese as a Foreign Language Class*

Bao Rui Zhejiang Normal University

Abstract Learner participation and the interaction in classroom is a necessary condition for L2 learning.Informed by sociocultural theory, this study explored how the teacher’s language use affected learner participation in a Chinese as a foreign language (CFL) classroom. A researcher videorecorded their own class at a Danish university. The microgenetic analysis of the data indicated that there are several methods the teacher should use to promote learner participation. These methods included creating an interactive space for learners, involving students in problemsolving, and providing ample opportunities to communicate with their teacher. However, some features of teacher language use were not conducive to L2 learning, as they deprived learners of participating in interaction by limiting learners’ opportunities to reflect on their L2 use and interrupting the flow of learner discourse. This reflective inquiry casts light on teachers in terms of how to use their language to make classroom interaction more favourable for L2 teaching and learning. Also, it produces insight into teacher education programs by having reflective practice on its agenda so as to better enhance teacher teaching skills.

Key words sociocultural perspective; teacher language use; learner participation; Chinese as a foreign language

1. Introduction

Classroom interaction is jointly managed by the participants: the teacher and learners. However,their contributions are asymmetrical. In general, the teacher plays a major role while learner participation is limited (Walsh, 2002). With the growing recognition of the social dimension of L2 learning (Block, 2003),researchers have focused on the importance of learners’participation in classroom learning process. Given that language is the essential tool used by teachers to manage classroom interaction, it can be assumed that any endeavour to enhance learner participation should start by investigating the teacher’s use of language.The literature has well documented the impact of teacher language use on learner participation and L2 learning opportunities (Martin-Beltrán, 2012; Smiley& Antón, 2012; Walsh, 2002; Walsh & Li, 2013). This line of research has focused mainly on Indo-European languages, especially English. However, knowledge about other languages such as Chinese is rather limited. Due to the differences between Indo-European languages and Chinese, questions have arisen in regard to the applicability of the results of the existing L2 research to Chinese (Bao, 2020a; Duff & Li, 2004). This highlights a need for more inquiries in this area.

Over the past decade, teaching and learning Chinese as a foreign language (CFL) has witnessed dramatic growth in many countries and regions. However, this growth has been accompanied by various challenges.On one hand, Chinese with its unique pronunciation system makes it extremely challenging for non-native speakers (Hu, 2010; Shen, 2005); on the other, CFL teaching is primarily dominated by a teacher-centred approach, which is not congruous with local Western educational practices, thus resulting in an unpleasant learning experience for CFL learners. This results in decreased motivation and even discontinuation of learners further study (Bao & Du, 2015; Ke & Li, 2011;Orton, 2011). As such, the need for improvements in CFL teaching and learning is self-evident. Various efforts have been taken such as teacher training and professional development (Everson & Xiao, 2009),innovation in Chinese pedagogy (Moloney, 2013;Moloney & Xu, 2016), and the acquisition of specific Chinese grammar (Jiang, 2009). Nevertheless, little attention has been paid to the classroom learning process, especially in relation to the teacher’s use of language and learner participation.

Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to fill this gap by exploring the effect of teacher language use on learner participation in a CFL class. Informed by sociocultural theory, a reflective approach was used,as it is helpful for teachers to observe, evaluate, and reflect on their teaching in a systematic manner (Walsh,2011). The results are expected to inform CFL teachers in terms of how to make their language use more effective for Chinese teaching and learning.

2. Theoretical framework: A sociocultural perspective on L2 learning

The fundamental premise of sociocultural theory is that human cognitive development, including L2 learning, is not an individual but a social activity.According to Vygotsky (1978), there are two different but interconnected levels of cognitive development.One is the actual level of development, in which the individual is able to perform a function independently.The other is the potential level, where an individual achieves a higher level of performance with the assistance of a more knowledgeable adult or peer. The gap between the two developmental levels is referred to as the zone of potential development (ZPD), which,in Vygotskian’s view, needs to be bridged in order to facilitate learning. Central to this learning process is the mediation through which an expert utilizes a variety of tools to aid the individual performing a function that cannot be accomplished initially. Among these tools, Vygotsky (1978) attached great importance to symbols, primarily language. Language is a tool for communication and also a cognitive tool that shapes and reshapes our thoughts. This function of language has blurred the distinction between language use and language learning. Specifically, language learning is mediated by the use of language, which,in turn, facilitates language learning. A sociocultural perspective of L2 learning requires learners to participate in constructing their own L2 knowledge through dialog with other participants, which advances their ZPD (Ableeva & Lantolf, 2011). This social and mediated view of learning has profound implications for L2 classroom teaching and learning.

Under this method, teaching is no longer a linear process of knowledge transmission from teacher to learners, but rather an assisted process in which the teacher helps learners to constantly improve their ZPD(Ableeva & Lantolf, 2011). Vygotsky (1986) argued that teaching becomes effective only when it triggers a range of functions that move students along within the ZPD. This entails the teacher to create adequate space for learners to practice their L2 skills which enables them to bridge the gap within the ZPD. Given the fact that language is the essential tool teachers use,it is reasonable to say that the quality of the teacher’s language use directly relates to learner participation and subsequent opportunities for L2 learning. In light of the purpose of the current study, the following review is framed within the context of sociocultural theory.

3. Literature review

3.1 Research on teacher language use and L2 learning

A number of studies have examined the effects of teacher language use on L2 learning. For instance,Antón (1999) explored teacher-centred discourse and learner-centred discourse in L2 French classes and identified that during learner-centred discourse, the teacher’s language use provided learners with more opportunities to participate in the learning process,while teacher-centred discourse resulted in little space for learner participation. This study highlights the quality of teacher language use in determining the extent of learner participation and the opportunities for learning. Smiley and Antón’s (2012) investigation on the role and strategies of an L2 Spanish teacher in mediating high-school learners engagement during class also indicated that teacher language use is critical to encouraging learners to stretch their L2 skills. In Van Compernolle’s (2010) study, he found that the L2 French learner’s incidental microgenetic development was oriented by the teacher’s speech, which means that the teacher language use directly related to L2 learning opportunities.

Research has also investigated the strategies the teacher used to mediate learner involvement in L2 classes.For instance, Walsh and Li(2013), two ESL teachers in China, provided space for learner participation by increasing answer wait-time, extending learner turns,reducing teachers’ echo, shaping learner responses,and ensuring their language use aligned with the pedagogical goal of the class. Da?kin’s (2015) study on a teacher’s strategies in shaping learner contribution in a Turkish EFL classroom indicated that apart from interactive strategies such as meaning negotiation,the use of elaborated questions and writing on the board helped enhance learners’ participation, which suggested that the nature of teacher language use may vary in different contexts. The above-reviewed research has indicated the role of teacher language use in L2 learning. However, this line of research has mainly focused mainly on European language learning contexts. Little is known about teacher language use in other contexts, particularly in relation to the context of CFL teaching and learning.

3.2 Research on Chinese as a Foreign Language

Research on Chinese language has long been focused on its grammatical features from a linguistic perspective. Over the past decade, with the number of CFL learners abroad growing, issues related to CFL teaching and learning have been brought to the fore. Some researchers have examined the effect of implementing different approaches on CFL teaching(Bao & Du, 2015; Moloney & Xu, 2016; Wu, 2018).Some have examined Chinese character reading and learning strategies (Shen & Ke, 2007). Others have focused on issues related to CFL teachers, such as their beliefs, identities and professional development (Bao,2019; Moloney & Xu, 2015). In addition, the status quo of CFL teaching in different countries has been also reported (Ke & Li, 2011; Zhang & Li, 2010). One study worth noting is Bao’s (2020a), which examined the interaction of CFL learners’ by focusing on language-related episodes and revealed that beginner CFL learners benefited from collaborative dialogue generated during task-based activities. However, this benefit was affected by the factors such as learner proficiency, tasks, pair dynamics, individual learner differences, and the linguistic features of Chinese language. Similar findings were also identified in Bao’s (2020b) study, which investigated CFL learners’interaction and its connections to their learning. In summary, the existing research has focused mainly on the effect of external means such as curriculum design,teaching methods, digital tools, and textbooks on CFL teaching. Although there have been some studies that addressed Chinese teacher language use, with a focus on describing the proportion of different types of teacher talk such as teacher questions, corrective feedback and assessment, etc (Liu et al., 2014; Wang,2019), very few studies have focused on the interaction between teachers and learners, especially from a sociocultural perspective. The current study aims to address this gap by examining Chinese teacher language use and learner participation. The following research questions were formulated:

1. How does the teacher language use promote the opportunities for learner participation in teacherlearner interactions in a CFL class?

2. In what ways does the teacher language use reduce opportunities for learning?

4. Methodology

4.1 Action research

Unlike the mainstream research that dominates second language teaching, action research is conducted by teachers in their classrooms for their own purposes.It is “simply a self-reflective inquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the effectiveness of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out” (Carr & Kemmis,1986: 162). Action research is often motivated by an interest in or concern about some aspects of a teacher’s professional performance (Wallace, 1998). Action research is useful in helping teachers raise awareness and improve certain aspects of their teaching practices(Richards & Schmidt, 2002). It is a recursive cycle that includes a few key concepts: the identification of a focus, observation, data analysis and interpretation,and reflection. This study documents the first cycle that intends to help the teacher to obtain an in-depth understanding of their language use and its effect on learner participation.

4.2 Contexts and participants

This study took place in a beginner-level CFL class within the program of China Area Studies at a Danish university. The class was two semesters long, focusing on oral skills. As for the instruction,it generally consists of two parts: teacher-fronted interaction, where the teacher focuses mainly on grammar explanation and guides students to practice grammatical forms in Chinese; and learner-learner paired or group work, where learners work together on the given task. The teacher and author of this paper is a native Chinese speaker with four years of teaching experience in Denmark. Due to the teacher’s limited proficiency in Danish and the students’ high proficiency in English, English is mainly used as the instructional language for grammar explanations or classroom activity management.

There were fiTheen participants in the mentioned class.They were all native Danish speakers, except for one Lithuanian student who had a near-native proficiency in Danish. Their ages ranged from 22 to 29 years old.They met for 90-minute teaching session per week,and each semester has 10 weeks. Participants had neither experience in learning Chinese language nor any contact with Chinese outside the classroom. They were considered novice learners. The class had a fixed textbook titled “Integrated Chinese”. A mandatory exam is taken at the end of the second semester.

4.3 Data collection

Data collection was conducted throughout the first semester of the above CFL class, which began in the fall of 2018, for a total of 900 minutes of recordings. It should be noted that this study focused exclusively on teacher-student interaction, specifically, “interactions controlled and directed by the teacher” (Rulon& McCreary, 1986:182). To capture this dynamic interaction, a camera was set up at the front of the classroom. The analysis presented here was based on four teaching sessions: the third, fifth, eighth, and tenth. These sessions consisted of approximately 6 hours of recordings of classroom interaction. It is assumed that the detailed analysis of these interval lessons would present a more complete picture of teacher language use throughout the class. The recordings were transcribed by the researcher, who was also the author of this paper. Learners’ oral Chinese was transcribed intopinyinwith tone markings, a phonetic system used to represent the pronunciation of the Chinese language. Transcriptions can be seen in the Appendix.

4.4 Data analysis

Informed by the sociocultural perspective of learning,two levels of analysis were carried out. At the first level,through repeatedly reading the transcriptions, teacher language use was open-coded into two categories:promoting learner participation and inhibiting learner participation. Afterwards, the same coding process was conducted by assigning codes to different features of teacher language use within each category. Then,through an iterative examination on these assigned codes, axial coding was used to merge similar features of teacher language use into identical theme, which ultimately established three themes under the category of ‘promoting learner participation’ and two on that of‘inhibiting learner participation’. At the second level,microgenetic analysis was performed, as it enables researchers to document moment-by-moment changes taking place over a very short span of time (Lantolf,2000). These changes, from a sociocultural perspective,are perceived as “a means of understanding the development of higher psychological processes”(van Compernolle, 2010: 68), which means learners’increasing ability in L2 language. In other words,teacher language use activated learners’ ZPD by encouraging them to participate in verbal interaction and enabling them to achieve a high-level performance that cannot be accomplished alone. In this way, the teacher’s language use facilitates their L2 learning.Conversely, teacher language use deprived learners of the opportunity to participate, which failed to activate their ZPD and resulted in missed learning opportunities. According to this, the data was analysed by focusing on the episodes selected from each theme under the two categories in which there were overt signs of how teacher language use affects opportunities for learning.

In addition, considering the dual role of being the teacher and the researcher in the present study, other perceptions were taken into account to enhance the reliability of the coding (Stake, 2000). As such, 30%of the two levels of analysis presented above were reexamined by another L2 researcher. Disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached and any analysis that failed to come to an agreement was excluded. The final findings are presented in the following sections.

5. Findings

The microgenetic analysis of the data centred on the two research questions mentioned above. The results were presented individually. Due to limited space,the following findings focus on a few representative extracts.

5.1 The teacher language use promoting learner participation

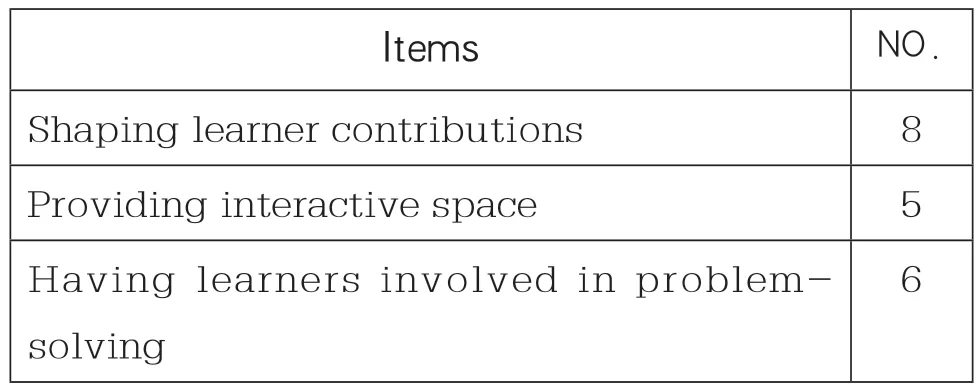

Data analysis identified three features of teacher language use that promoted learner participation in teacher-learner interactions: shaping learner contributions, providing interactive space, and having learners involved in problem-solving, which has occurred in different frequency (See Table 1).Also, it should be noted that these features were not independent of each other but rather were sometimes interwoven in one extract.

Table 1. The teacher language use promoting learner participation

5.1.1 Shaping learner contributions

The term “shaping learner contributions” was adopted from Walsh (2011:168), which was defined as “taking a learner response and doing something with it rather than simply accepting it”. Doing so entails learners drawing on their L2 resources and manipulating them in a sensible manner. Extract 1 was part of a communicative activity in which the teacher intended to situate learners to learn vocabulary at the beginning of the lesson.

Extract 1

1T: Yeah delicious, hǎo, nǐxǐhuan dānmàicài háishì měiguócài? Ck.

Yeah delicious, well, do you like Danish food or American food? Ck.

2Ck: Eh, wǒ xǐhuan, eh, měiguócài.

Eh, I like, eh, American food.

3T: Wèishénme?

Why?

4Ck: Yīnwèi, eh (3), wǒ xǐhuan měiguócài hǎochī.

Because, eh (3), I like American food is delicious(incorrect).

5T: Ah? Yīnwèiwǒ=

Ah? Because I=

6Ck: =Yīnwèi wǒ, eh (3), měiguó… eh, how where should I place ‘hǎocài’?=Because I, eh (3), America…eh, how where should I place ‘delicious’?

7T: ‘Hǎochī’ just means delicious so then yīnwèi ‘American food is delicious’ just like this.

‘Delicious’ just means delicious so then because

‘American food is delicious’ just like this.

8Ck: Yīnwèi měiguó shì hǎochī.

Because America (‘American’ should be used) is delicious.

9T: Měiguócài.

American food.

10Ck: Oh, yīnwèi měiguócài hǎocài.

Oh, because American food is delicious.

11T: Hǎocài? (laughing)

Good dish?

12Ck: Hǎochī.

Delicious.

This extract indicated that how the teacher shaped the learner’s non-target speech until he appropriately produced the target word “hǎochī”. The shaping started with the teacher’s open-ended question in line 3,which functioned as an invitation for the learner to elaborate upon the answer he provided in line 2. This question elicited Ck’s long and complex response in line 4. However, since this response was non-target,it became the focus of the rest of the shaping in lines 5-12. First, there was the discourse marker (ah?) with a rising intonation, followed by the teacher repeating Ck’s response in line 5, which served as a request for clarification. This request was correctly understood by Ck, as demonstrated by his latched turn at line 6,in which he tried to reformulate his response but was interrupted by two long pauses, indicating his diftculty in doing so. This was further evidenced by his explicit request for help with the appropriate use of the target word, “hǎochī,” which was mispronounced as “hǎocài”in the same line. Up to this point of interaction, the teacher’s shaping became more specific by providing a recast “hǎochī” accompanied by a direct translation,after which the communication was handed back to the learner by the teacher, who used English to expect the learner to produce the target form. This specific shaping was accomplished through communicative moves such as “so then ‘American food is delicious’ just like this.” In turn 8, Ck correctly incorporated “hǎochī,”but misused the target word “měiguó,” instead of producing “měiguócài.” The exclamation “oh” indicated Ck’s internal awareness of his misuse following the teacher’s partial recast (line 9), as was evident by his comprehensive utterance with “měiguócài”in line 10. However, the target word, “hǎochī,” was mispronounced again. Following a confirmation check from the teacher (line 11), Ck successfully self-corrected his pronunciation in turn 12.

5.1.2 Providing an interactive space

“Interactive space” refers to the space for learner participation and engagement (Walsh & Li, 2013). In the data, there were many instances in which teacher language use provided learners with this kind of space.As shown in extract 2, the teacher was checking the learners’ comprehension after describing a family photo in the form of question-answer.

Extract 2

1T: Hǎo, zhège nánrén, oh, zhège nánháizi shì shéi? Dn.

OK, who is this man? Oh, this boy? Dn.

2Dn: Um(4).

3T: Zhège nánháizi shì shéi?

Who is this boy?

4Dn: Zhège zhège BàoRuǐ mèimei de érzi.

This this boy is (missing the pronoun and verb)BàoRuǐ’ s younger sister’s son.

5T: Ah, hěn hǎo zhège: (pointing to the following words on the blackboard).

Ah, very good this: (pointing to the following words on the blackboard).

6Dn: Zhège nánháizi shì BàoRuǐ mèimei de eh háizi.

This boy is BàoRuǐ’s younger sister’s eh…child.

7T: Duì duì duì, zhège nánháizi shì BàoRuǐ mèimei de háizi or érzi. Zhège nǚháizi shì shéi? Ck.

Right right right, this boy is BàoRuǐ’s younger sister’s child or son. Who is this girl? Ck.

Here we can see that the teacher started with an openended question and selected Dn for the interaction.In line 2, the hesitation form (“um”) followed by a four-second pause functioned as a planning time for Dn. Following this pause, the teacher repeated her question in line 3, expecting a response from the learner. This planning time and repetition seemed helpful, as shown in line 4 where Dn came up with an answer in which two words were missed. Dealing with this non-target production, the teacher acknowledged it by uttering the exclamation “ah,” accompanied by a positive assessment (“hěnhǎo”). Following this assessment, the teacher reiterated the first two words in Dn’s production, elongating the final sound and using a gesture to point to the following word needed for the ideal answer. These signals were interpreted as a request for clarification, as Dn extended her turn by adding the missing words and completing the answer,with the allowance of a relatively long waiting time in line 6. This answer was solidly confirmed by the three successive “duì” from the teacher, who also repeated it as an example for the benefit of the whole class, even as she immediately directed a similar question to another learner.

5.1.3 Having learners involved in problem-solving

In the data, teacher language use promoted learner participation while involving learners in the problemsolving process instead of directly providing them with answers. In extract 3, the teacher and students were engaging in grammar usage reflection by focusing on the sentences that most students were incorrect when translating them into Chinese as required in their homework.

Extract 3

1T: Hao, zhè shì LiúXīng de zhàopiàn (pointing to the photo in the slides). Zhège ne? ‘Here is the photo of her older sister’ Ck.

Ok, this is LiúXīng’s photo. What about this? ‘Here is the photo of her older sister’ Ck.

2Ck: Zhè shì, eh, zhàopiàn, eh, de jiějie.

This is, eh, older’s sister’s photo (wrong word order).

3T: Zhè shì zhàopiàn de jiějie.

This is, eh, older’s sister’s photo.

4Ck: Jiějie.

Older sister.

5T: Zhè shì LiúXīng de zhàopiàn. This is LiúXīng’sphoto. Zhè shì LiúXīng de zhàopiàn. Zhège zěnmeshuō? (pointing to the sentence on the blackboard)

This is LiúXīng’s photo-This is LiúXīng’s photo-This is LiúXīng’s photo. How to say this?

6Am: Tā shì wo de zhàopiàn.

It is my photo (wrong meaning).

7T: Zhège ‘her older sister’.

This ‘her older sister’.

8Am: Tā de jiějie.

Her older sister.

9T: So zài shuō yí biàn (with outstretched hand).

So say it again.

10Am: Zhè shì wo de zhàopiàn de tā de jiějie.

This is my older sister’s photo (wrong in the order).

11T: Sl (raising her hand).

12Sl: Zhè ge wo jiějie de zhàopiàn.

This is my older sister’s photo (missing the verb).

13T: Yeah, zhè shì ‘her’.

Yeah, this is ‘her’.

14Ss: Tā.

Her.

15T: Duì, tā jiějie.

Right, her older sister.

16Sl: Ah, tājiějie de zhàopiàn.

Ah, her older sister’s photo.

This extract showed how learners were involved in finding a solution to the question presented in turn 1. First, the teacher asked the question and provided examples to simplify the task for Ck, who was brought into the interaction by nomination in line 1. Ck provided a non-target response in line 2.By repeating Ck’s response (line 3), and the same example two more times along with a translation (line 5), the teacher clarified her intention to have learners provide an answer by posing her leading question,“zhège zěnmeshuō?” in line 5. Am volunteered an answer in line 6 but it was incorrect. The teacher continued to provide metalinguistic support by highlighting the target word (line 7) and requesting clarification (line 9). Obviously, this support was not enough for Am, who came up with another non-target response in line 10, while these on-going exchanges seemed adequate for Sl, who raised her hand as a signal for her contribution. The teacher immediately gave Sl a turn, who uttered her answer fluently but misused the pronoun “wǒ” and the Chinese classifier “gè”, which,however, was very close to the ideal answer. The teacher first acknowledged Sl’s contribution by saying “yeah,”and continued to push her by giving the partial recast“zhè shì” and highlighting the pronoun “her” in line 13. Sl was aided by other peer learners’ verbalization of the target pronoun “tā” in line 14, and by the teacher’s partial modeling in line 15. The discourse marker“ah” externalized Sl’s awareness of her misuse of this pronoun, which is followed by incorporating “tā” into her partial production in turn 16.

5.2 The teacher language use reduces opportunities for learning

The results showed two features of teacher language use that inhibited learner participation. They are limiting learners’ ability to reflect on their L2 use and interrupting the flow of learner discourse, which has occurred with different frequency (See Table 2). Each is presented and discussed individually.

Table 2. The teacher language use reducing opportunities for learning

5.2.1 Limiting learners to reflect on their L2 use

This feature of teacher language use was mainly identified in the section of grammar explanation. In Extract 4, the teacher started the class by emphasizing several incorrect sentences that were found in the learners’ homework.

Extract4

1 T: So you got your homework, so then there is something I want to stress in the homework: hǎo.

Zhège ‘nǐ jiào shénme?’ (pointing to the sentence on the blackboard) What does this mean?

2 S: What is your name?

3 T: Yeah, what is your name? OK, what is your name?

Now I want to say tā what is his name? How do you say? (3) Then you change nǐ to tā right? Tā jiào shénme?

…But now I want to say zhège nánháizi.

What is this boy’s name? How do you say? (4) What is this boy’s name? How do you say this sentence? Dn.

4 Dn: Zhège nánháizi jiào shénme?

5 T: Yeah, zhège nánháizi jiào shénme? (writing this sentence on the board ) Zhège nánháizi jiào shénme? So then you don’t need to always say nǐ; it’s only when you are asked what is your name? Otherwise you have to change the subject, hǎo, zhèshì dìyī ge,kàn dì’èr ge ‘xiānsheng Wáng jiào Wáng Dōng’,zhège duì ma? Is this right? Can you say this? Duì ma?

6 S: Isn’t Wáng xiānsheng?

7 T: Duì women yào shuō Wáng xiānsheng remember, in China, the family name is always at the beginning,so Wáng xiānsheng. Like teacher Bào, you can’t say lǎoshī Bào, you have to say my last name. Bào lǎoshī.nǐhǎo (greeting one student who comes in). So family name is always at the beginning yeah hǎole (OK).

In the extract above, the teacher, as a knowledgeabletransmitter, did the most of the talking. In turn 1, the teacher framed the focus of the activity by saying “so you got your homework, so then there is something I want to stress in the homework.” after that, the teacher asked learners to answer different questions,which were presented in lines 1, 3, and 5. However,the purpose of these questions was to check whether the learners have mastered the ability to say these sentences in Chinese. While these questions did not stimulate learners’ further cognitive engagement in reflecting upon their L2 use, they may have the effect of holding learners’ attention. In contrast, once the learners correctly responded to these questions, the teacher provided a positive assessment, followed by a long and explicit explanation on relevant grammar rules as shown in lines 5 and 7. Although her explanation was clear and detailed, it was not clear whether learners understood this explanation or were able to use it appropriately, as they were not involved in using this grammar. In other words, teacher language use failed to afford learners the opportunity to reflect on or articulate their understanding of this knowledge.Ideally, instead of explaining herself, the teacher should have encouraged learners to do so through which focused on the learners’ ZPD and helped them for further development.

5.2.2 Interrupting the flow of learner discourse

As noted above, the focus of this class was on fostering learners’ oral competence. Thus, it is taken-for-granted that learners should be given opportunites to talk as much as possible during class. The extract below presents the exchanges in which learners were invited to report what they had heard after the teacher’s description of a family photo.

Extract 5

1Yb: Tā de shēngrì shì, eh, shíyuè èrshí’èr hào.

His birthday is on the 22nd of October.

2T: Hěn hǎo.

Very good.

3Yb: …Eh, xīngqīwǔ (wrong in the meaning).

…Eh, Friday.

4T: Ah? Tā de shēngrì shì shíyuè èrshíèr hào=

Ah? His birthday is on the 22nd of October.

5Yb: =Xīngqīèr.

=Tuesday.

6T: Xīngqīèr yeah more? We have so many things here.

Tuesday yeah more? We have so many things here.

7Yb: …LiúXīng de dìdi shì, eh, dōu shì xuéshēng.

…LiúXīng’s younger brother, eh, both are students.

8T: En, hěn hǎo.

En, very good.

9Yb: …LiúXīng dìdi shì, eh(3), shí suì.

…LiúXīng’s younger brother, eh (3), is ten years old.

10T: Shí suì yeah, Dn, can you continue?

Ten years old yeah, Dn, can you continue?

11Dn: LiúXīng bàba hé mama dōu shì yīshēng.

Both LiúXīng’s father and mother are doctors.

12T: Hěn hǎo, hěn hǎo.

Very good, very good.

13Dn: Hé LiúXīng… de LiúXīng jiějie shì dàxuéshēng.

And LiúXīng’s…LiúXīng’s older sister is a university student.

14T: En, hěn hǎo[NAME].

En, very good [NAME].

In this extract, the teacher, as a gatekeeper, assessed learners’ oral productions. Throughout the exchanges,she provided frequent positive assessment (“hěnhǎo”)following the learners’ long and complex utterances,as shown in lines 1, 7, 11, and 13. Though the teacher intended to confirm and encourage the students,they interrupted the flow of the learner’s discourse as evidenced by relatively long pauses before their next productions (lines 3, 9). In addition, while teacher echo is helpful for letting the whole class hear other learners’ contributions or for signaling a clarification request via rising intonation (Warring,2008), the teacher’s echo appearing in lines 6 and 10 may have also deprived learners of space for potential participation. Certainly, the point here is not to deny the value of positive assessments and teacher echo during interactive exchanges, but rather to highlight the importance of how teacher should use language.Imagine if the teacher had not given these assessments until learners had completed their entire contributions.The student might have produced more coherent,smooth, and complex responses, or creative uses of the target language. As such, avoiding positive assessment is likely to create more learning opportunities(Warring, 2008). In addition, the frequent use of these assessments and teacher echo also might have led to a deviation from the pedagogical goal of the observed class—building up learners’ oral ability as noted above.This deviation, as argued by Walsh and Li (2013), is also counter-productive for L2 learning.

6. Discussion

The results indicated that the teacher language use related directly to opportunities for L2 learning.Specifically, when the teacher language use constantly shaped learners’ utterances through various strategies such as elaboration question, clarification requests,translation, emphasis, recasts, and confirmation check,it created more opportunities for learner participation in making sense of their own utterances. This adds support for what previous research has reported(Da?kin, 2015; Simley & Antón, 2012). These ways of teacher language use, from a sociocultural perspective of learning, have not only activated learner’s ZPD but also extended it to a higher level in which he/she can produce the utterances in a targeted manner.This accomplishment indicates learner’s increasing L2 competence, which may not have been achieved without their participation (Gánem-Gutiérrez, 2013;Walsh, 2002). In this sense, it can be said that these ways of teacher language use are conducive to L2 learning, which should encourage L2 teachers to use them during classes.

In addition, the teacher, through her use of language,also prolonged her waiting time instead of filling in the silences that occurred during exchanges. In doing so,it provided space for learners to have second thoughts and reconstruct their answers, the result of which is conducive to learners’ cognitive development. As Walsh and Li (2013) maintained that teacher language use might create more opportunities for L2 learning by providing and managing space for learner participation instead of filling in the silence. Contrarily, this learning opportunity might have been missed if the teacher had simply filled the silences by giving a direct answer,which frequently happened during teacher-centered discourse (Antón, 1999). Certainly, there are good arguments for teachers to do so in terms of moving the class forward or preventing learner embarrassment(Walsh, 2002). However, from a sociocultural perspective, filling the silences might have failed to enable teachers to activate learners’ ZPD, thus reducing opportunities for learning.

Last but not least, the results indicated that unlike providing an off-shelf answer, the teacher drew on various interactive strategies in terms of highlighting,repetition, metacognitive support, clarification requests, and modeling to have learners involved in figuring out the problem being discussed. What made this involvement important is that it is not only likely to activate a range of functions that assist in learners’potential developmental level but also mediates learners to gain increased control over these functions,en route to ultimate independent performance (Van Compernolle, 2010). As such, this involvement also has contribution to learners’ L2 development.

Taken together, the results revealed the effect of the quality of teacher language use on learner participation and subsequent opportunities for L2 learning.Specifically, when teacher language use shapes learner contributions, provides learners with interactive space,and involves learners in problem-solving process, it promotes learners themselves to take responsibility of their own L2 understanding and knowledge, thus leading to more opportunities for L2 learning (Simley& Antón, 2012; Walsh & Li, 2013). On the other hand,learning opportunities will be reduced when teacher language use inhibits learner participation in the meaning-making process. These results are resourceful for CFL teaching.

7. Implications for CFL education

First, this study implies the importance of selfreflection in improving teacher instructional practices.Reflective practice is considered as an effective tool for improving L2 classroom teaching, as it enables teachers to critically think about their actions, become aware of their teaching behaviors, and construct their professional knowledge (Johnson & Golombek, 2002).As such, the reflective study here would help raise the teacher’s awareness of their own language use on the basis of which adjusts their teaching to be more effective. This is particularly applicable for those CFL teachers with Chinese educational backgrounds, as their culture-related beliefs about themselves and their role in classes greatly impacts their teaching behaviors, which hardly alter even in a new different context (Moloney & Xu, 2015). This impact may well explain why teacher-centered method is still popular in many CFL classrooms worldwide (Bao & Du, 2015;Orton, 2011). Keeping this in mind, for a fundamental change in CFL teaching, it may be more essential for teachers to reflect on their teaching practices instead of blindly taking so-called effective methods derived from English teaching and applying them.

Second, this study suggests the need to reconceptualize the role of the teacher in CFL classrooms. As discussed above, learning opportunities are enhanced when learners engage in constructing their L2 knowledge through the talk with their teacher, In other words,classroom learning is accomplished by the teacher and learners. This, from a social-cultural perspective of learning, encourages teachers to reconceptualize their traditional role of being a knowledge-transmitter shaped by Chinese education culture (Bao, 2020a; Hu,2002) to a facilitator who mediates learners to move through their ZPD.

Last but not least, this study is informative for teacher education program on how to assist both prospective and in-service Chinese teachers to improve their teaching practices. By perceiving learning as a sociallyconstructed process in which language is crucial, this study offers a new lens of teaching that emphasizes the role of teacher language use in L2 teaching and learning. This lens is insightful for Chinese teacher education programs by prioritizing interaction,teacher language use, and learner participation instead of focusing on the Chinese language teaching methods they’re used to. By doing so, this generates new knowledge and improvements in teaching and learning. ATher all, classroom teaching is a complicated process and teaching method is just one aspect of this process.

8. Conclusion

This study investigates the effect of teacher language use on learner participation in teacher-learner interaction in a CFL class. Informed by a sociocultural perspective of learning, the results indicated that when teacher language use shaped learner contributions,created interactive space for learners, and had learners involved in the problem-solving process, it promoted learner cognitive engagement in constructing their L2 knowledge, thus leading to more opportunities for learning. This is in contrast to when teacher language use limited learners to reflect on their L2 use and interrupted the flow of learners’ discourse, the result of which hindered learners from participating in interaction and missing learning opportunities. This study casts light on the role of teacher language use in L2 teaching, learning and the value of reflective practice for L2 teacher professional development.

Nevertheless, some limitations are worth noting in this study. First, the cross-section nature of the present study means whether the teacher has changed the way of her language use that hinders learner participation in her future teaching practices remains unknown.Second, one single data resource used in the present study may have inhibited us from fully interpreting the dynamic interactive process and the underlying reasons. Thereby, another source of data is greatly needed in further studies. Last but not least, although the researcher has taken care to use the language objectively and naturally, the dual role of being both teacher and researcher in the present study is not without problems. Despite these limitations, this study provides insights into CFL teachers’ ability to how to make language use more effective for teaching and learning. This insight would be a “gospel” for Chinese language teaching both in and outside of China.

Appendix A. Transcription system

T: Teacher SS: several students at once or the whole class Dn, Ck,Individual learner[ overlapping between teacher and student… pause of one second or less marked by three full stops? rising intonation, questions= turn continues, or one turn follows another without any pause Under underlined indicates speaker’s emphasis on the underlined portion of the word(Writing) give an explanation of what is happening in the background(4) silence; length given in seconds Want boldface words indicate incorrect pronunciation or form Italicised sentences with incorrect grammar