Formation of air-entraining vortices at horizontal intakes without approach flow induced circulation*

Mustafa GOGUS, Mete KOKEN, Ali BAYKARA

?

Formation of air-entraining vortices at horizontal intakes without approach flow induced circulation*

Mustafa GOGUS, Mete KOKEN, Ali BAYKARA

Civil Engineering Department, Middle East Technical University, Ankara,Turkey, E-mail: mgogus@metu.edu.tr(Received December 10, 2014, Revised October 5, 2015)

The aim of this experimental study is to investigate the effects of hydraulic parameters on the formation of air-entraining vortices at horizontal intake structures without approach flow induced circulation. Six intake pipes of different diameters were tested in the study. The intake pipe to be tested was horizontally mounted to the front side of a large reservoir and then for a wide range of discharges experiments were conducted and critical submergences were detected with adjustable approach channel sidewalls. Empiri- cal equations were derived for the dimensionless critical submergence as a function of the relevant dimensionless parameters. Availa- ble data is also checked for the possible scale effect. Then, these obtained equations were compared with the similar ones in the literature which showed a quite good agreement.

air-entraining vortex, horizontal intakes, model scale effect, sidewall clearance, vortex

Introduction

Vortex formation is a phenomenon occurs on the free surface in front of the intakes, it has great impo- rtance in the design criteria of the intakes. The loca- tion and direction of the intake should be so arranged that the water level should be well above the intake to prevent vortex formation even if the reservoir is at dead or minimum storage level. Alden Research La- boratory, ARL, defines six types of vortex formation[1]. The most critical one among these six vortex types is Type 6 where vortex formation causes air ingestion continuously. The vertical distance between the intake and the free surface is called submergence and the submergence where air-entraining vortex just occurs is defined as the “critical submergence”. Depending on the direction of the intake, the critical submergence can be measured from the center or summit point of the intake. For an effective intake, the submergence should be large enough to prevent occurrence of air- entraining vortices.

The main problems of air-entraining vortex for- mations are increase of head loss, reduction of intake discharge, reduction of efficiency of hydraulic machi- nes due to the lower discharge, operational problems at hydraulic machines, vibrations and cavitation[2]. Air-entraining can be removed by increasing the dista- nce of streamlines between the intake structure and free water surface, improving approach flow conditio- ns and applying some anti-vortex devices[1]. Borghei and Kabiri-Samani[3]and Kabiri-Samani and Borghei[4]investigated the effect of anti-vortex plates on forma- tion of air entraining vortex and critical submergence. Sarkarhed et al.[5]investigated the effect of intake headwall and trash rack on the type and strength of the intake vortices.

In literature, many researchers have worked to figure out and solve formation of vortices at intake st- ructures by comprehensive analytical and numerical methods. Many models and existing installations were examined by studies conducted at different intake ar- rangements, boundary and approach flow conditions. Researchers like Gordon[6], Knauss[1], Jiming et al.[7], Li et al.[8], Ahmad et al.[9]and Gürbüzdal[10]proposed empirical equations to find critical submergence. Ta?tan and Yildirim[11,12]and Yildirim et al.[13]studied flow conditions and formation of air entraining vorti- ces at vertical intakes. In addition, some of them men- tioned limits of the hydraulic parameters above which vortex formation is independent of these parameters.

1. Theoretical analysis

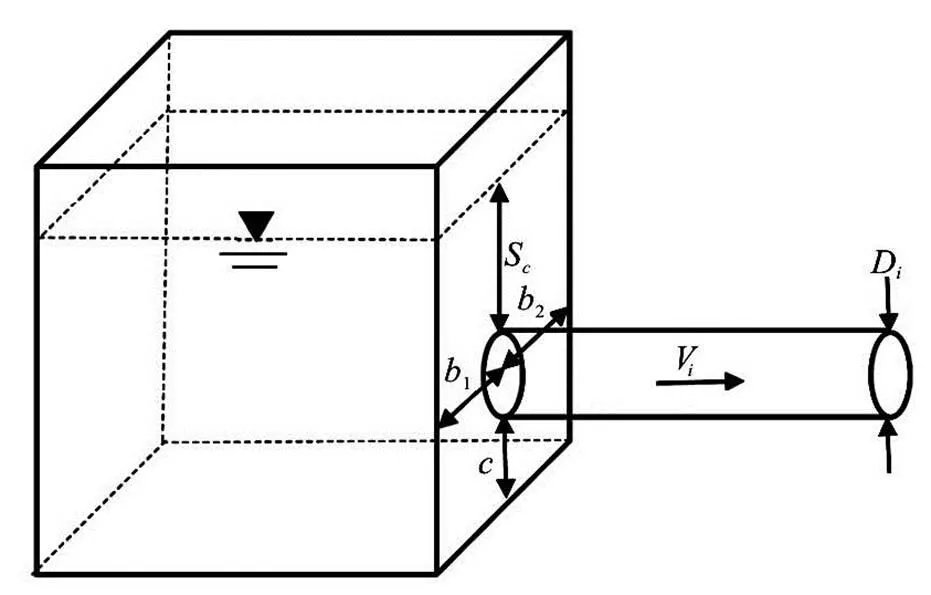

Since vortex formation is the consequence of the complex interaction between the geometry of the in- take zone and approach channel, the flow velocity and the liquid properties, parameters influencing vortex formation at a horizontal intake shown in Fig.1 may be expressed by

Fig.1 Basic illustration of the experimental intake

Based on dimensional analysis, critical submer- gence ratio,, was found to be the function of the following dimensionless parameters

In the experimental setup, the bottom clearance,, was so arranged that it is equal to zero all the time. Therefore,can be dropped from Eq.(2). In addi- tion, experiments were conducted at symmetrical flow conditions and consequently,andare equal. That is why these two parameters were combined and wri- tten asin the reduced form of Eq.(2). Circula- tion depends on the characteristics of the approach flow, the geometry of the intake chamber and the dis- charge. In the present study, since there is no imposed circulation and the flow and geometrical parameters of the intake are already in Eq.(1), the circulation para- meter,, could be removed from Eq.(2). In literatu- re, Weber number is accepted as it is effective in weak dimple like vortices and some of the researchers like Anwar et al.[14]stated that the effect of surface tension and viscous forces can be removed from the air-entrai- ning vortex equation ifandare greater than 104and 3×104, respectively. However, in this study, both effects of Weber and Reynolds number were investigated because these limiting values cover a wide range and they are valid only for their own studies. Froude number is the primary parameter affe- cting vortex formation because air-entraining vortex formation is a free surface phenomenon which is affe- cted by gravity. Also, model studies are generally undertaken based on Froude similitude. By conside- ring aforementioned explanations, the final form of the critical submergence ratio,, can be written in the following form

2. Experimental equipment and procedure

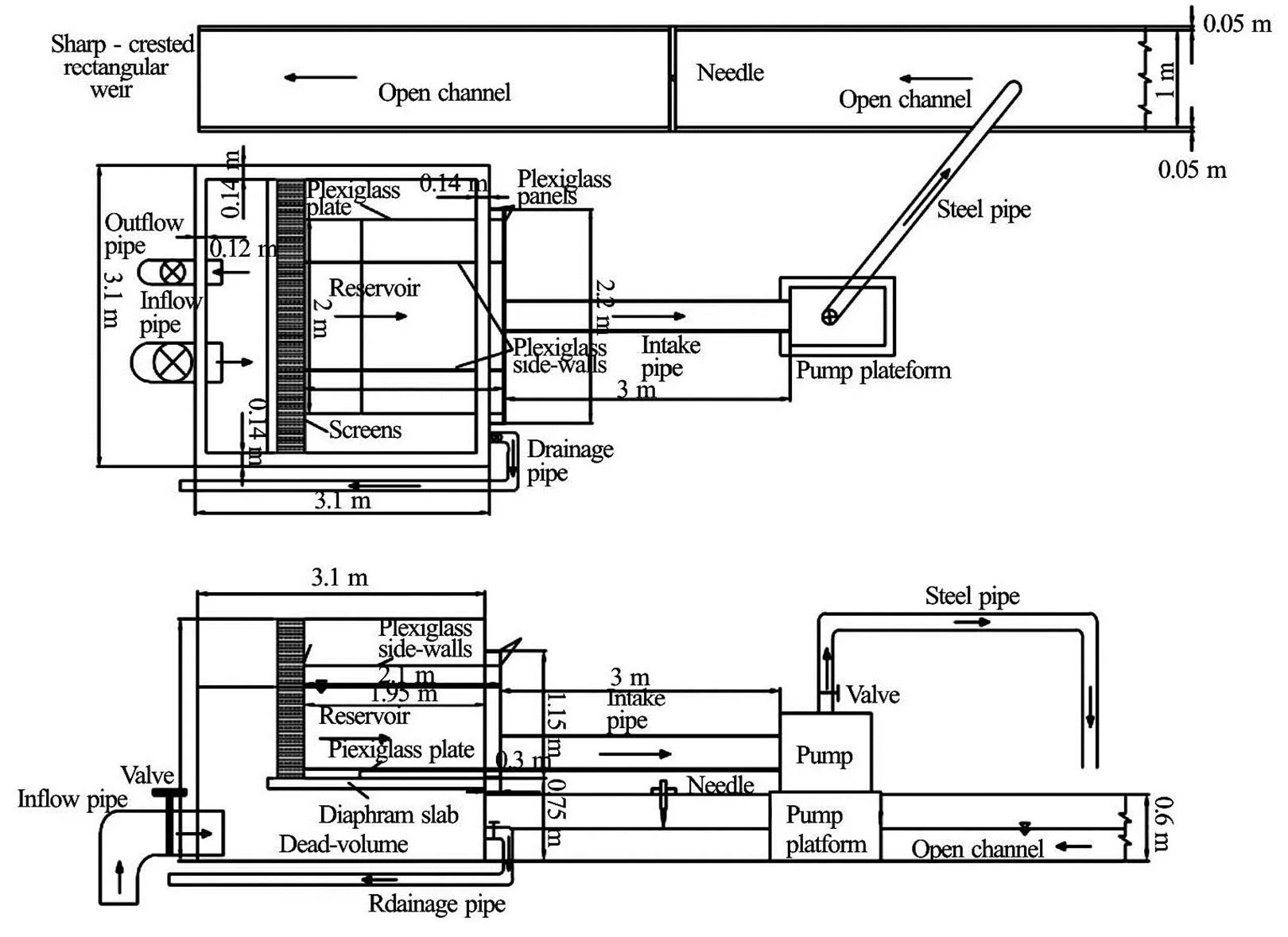

An experimental concrete rectangular reservoir was built to analyze the effects of hydraulic paramete- rs on the formation of air-entraining vortices at hori- zontal intakes[15]. The reservoir, shown in Fig.2, is 3.1 m in length and width and 2.2 m in depth and con- sisting of a dead-volume section, an active reservoir section and an intake section. A diaphragm slab was built to create a dead-volume section and active rese- rvoir section by dividing the reservoir into two parts in the horizontal plane and a 0.9 m space was left be- tween the slab and the rear wall of the reservoir so that water could reach the active reservoir part once the dead volume is filled. Screens were placed over the end of the slab and fastened to the reservoir side walls to provide energy dissipation of water and uniform motion of water without any waves and circulation in the reservoir. A part of front of the dead-end above the diaphragm slab, 2.2 m in length, 0.3 m in width and 1.2 m in depth, was extended from the reservoir front plane and was made of plexiglass panels to obtain a good observation behind the intake entrance. Two ple- xiglass side walls were placed orthogonally between the extended dead-end and screens and their location could be altered so that the effect of the side wall clea- rance on the formation of air-entraining vortices could be observed. Plexiglass intake pipes of diameters 0.3 m, 0.25 m, 0.194 m, 0.144 m, 0.1 m and 0.05 m were installed to the extended dead-end for each set of experiments in this order. After mounting the pipe of the desired diameter on this hole, a plexiglass plate was placed to the bottom of the reservoir so that the bottom clearance of the pipe would be zero. The in- take pipes were connected to a 10.0 kW centrifugal pump which conveys water to a steel pipe of 0.165 m diameter. Water fall freely from the steel pipe to an open channel which ends with a rectangular sharp-cre- sted weir. The calibration of the sharp-crested weir was done by using an acoustic discharge measurement device before the experiments were started. The requi- red flow is provided from a large elevated-constant head tank via an inflow pipe of 0.300 m diameter. In addition, a drainage pipe, to equalize the inflow to outflow, is connected to the front dead-end section.

Fig.2 Plan (top) view and side view (bottom) of the physical model

After installation of each intake pipe, the plexi- glass side walls were adjusted at required distances into the reservoir and the plexiglass plane at the bo- ttom was levelled accordingly, the experimental setup became ready for the experiment. In the experiments six different pipe diameters were used and for each pipe, six different side wall clearances (0.4 m, 0.6 m, 0.8 m, 1.0 m, 1.2 m and 1.4 m) were tested for a series of discharges. In each experiment, the discha- rge and water surface level were measured when an air-entraining vortex initiated.

To start the experiment, the inflow pipe was ope- ned and the reservoir was filled to a level which is above the critical submergence. Then, by turning on the pump and opening the valve on the pumping line, water was conveyed from the reservoir to the open channel. The openings of the valve on the pumping line, the inflow pipe valve and the drainage pipe valve were so arranged that the inflow was almost the same as the outflow. To make the observations under steady conditions, the water level was kept constant in the re- servoir for a considerable time, 5 min-10 min. After observing that there was no vortex formation in front of the inlet, by opening the drainage pipe valve at a very small amount, the water level was decreased gra- dually and then kept constant again for a considerable time for the second observation session of the free sur- face. This process was repeated several times until ob- serving the formation of swirls, surface depressions and finally air-entraining vortices on the free surface (This process took 30 min to 2 h for different experi- ments). At this point, the water level and the location of the formation of the air-entraining vortex were noted for that discharge. By changing the opening of the valve on the pumping line and the valve of the in- flow pipe, various values of discharges and the dimen- sionless numbers were obtained for each side wall opening and pipe diameter. This procedure was sta- rted with the maximum discharge provided by the pump with fully open valve on the discharge pipe and continued with reduced discharges by closing the valve at small rates until getting the minimum discha- rge which resulted in an air-entraining vortex. How- ever, for the plexiglass intake pipes with diameters of 0.10 m and 0.05 m, the tests were conducted at lower discharges in order to avoid cavitation.

3. Results and discussions

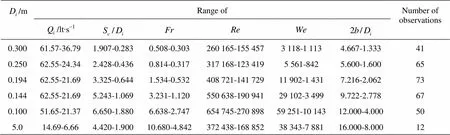

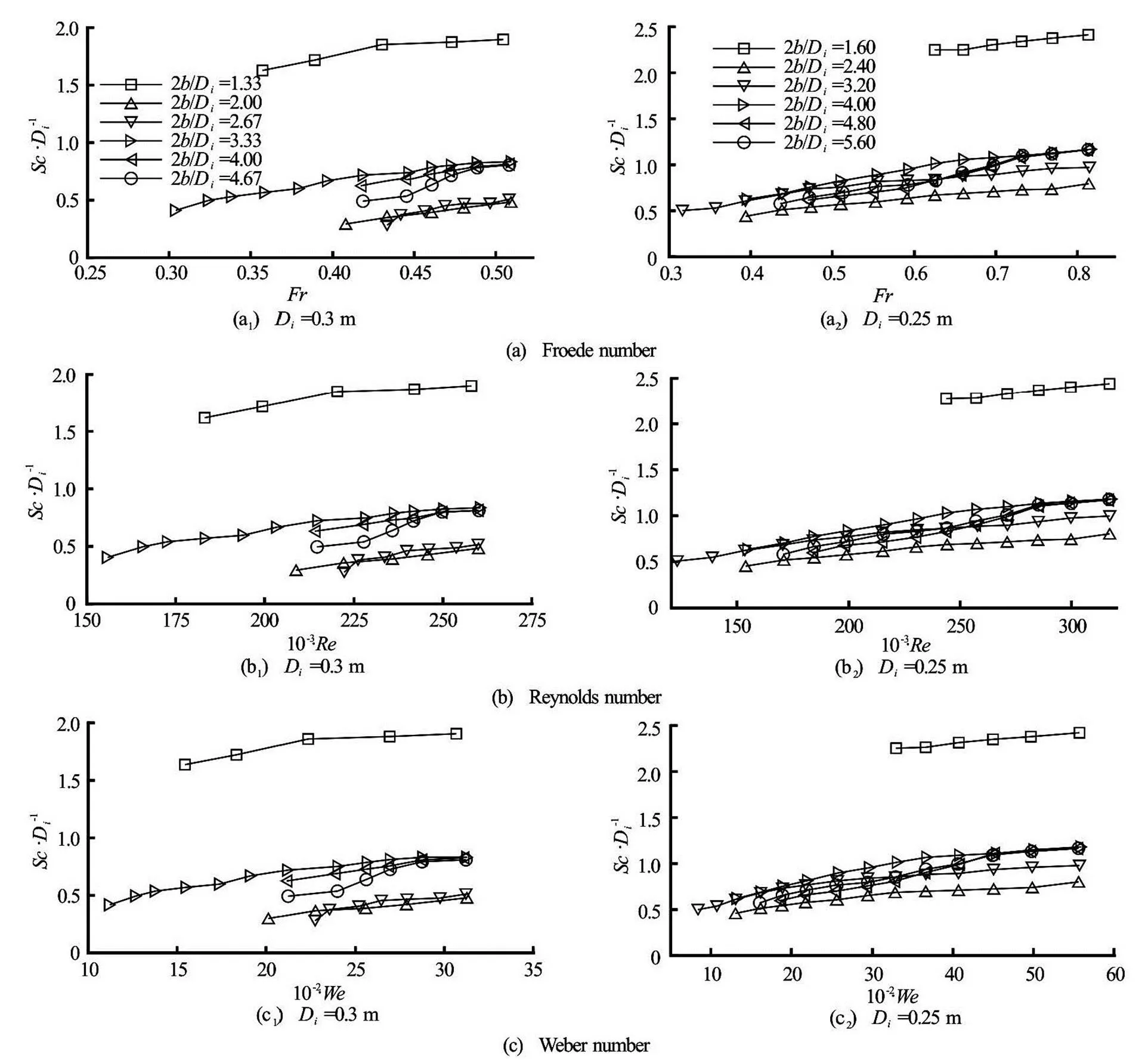

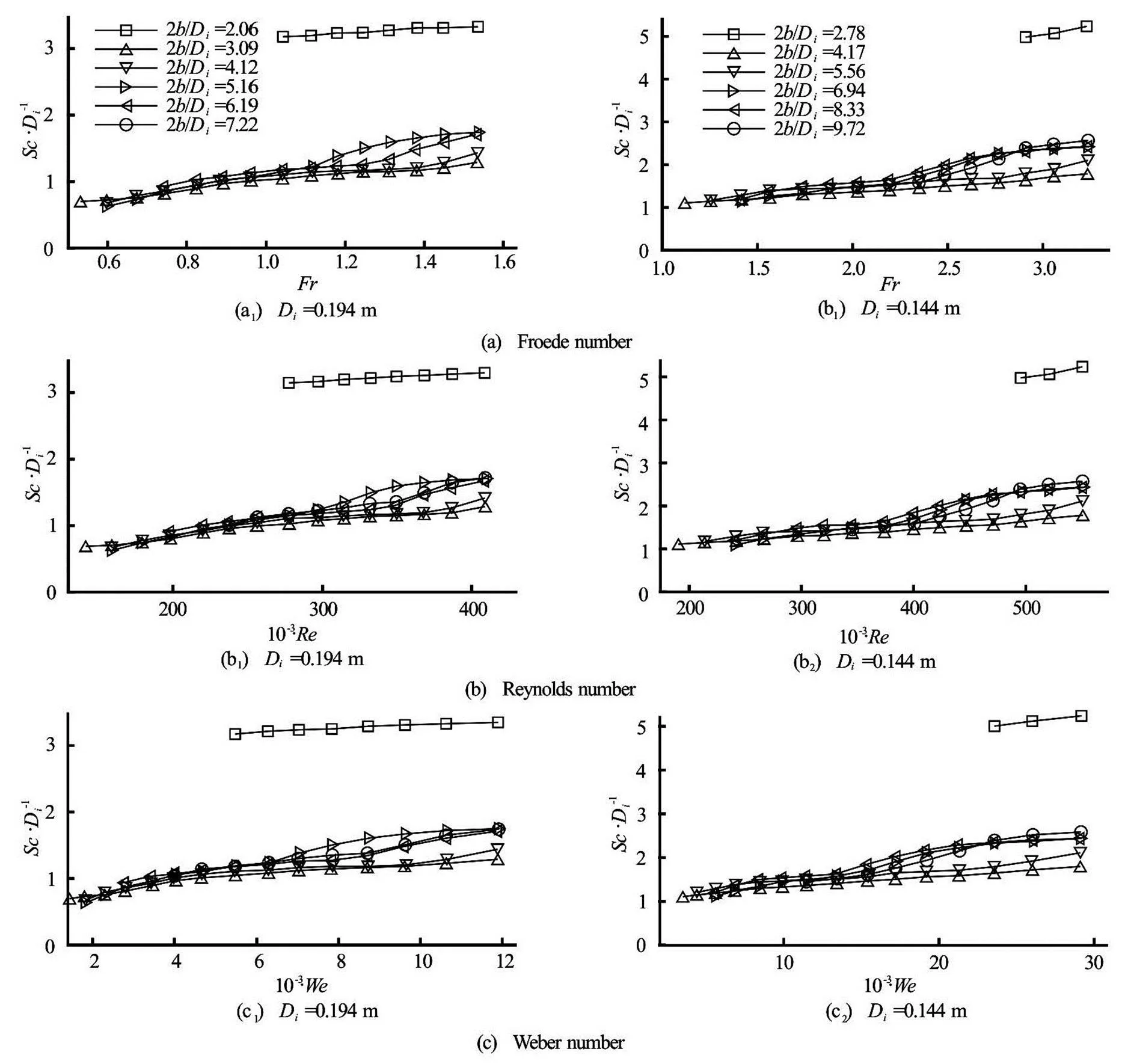

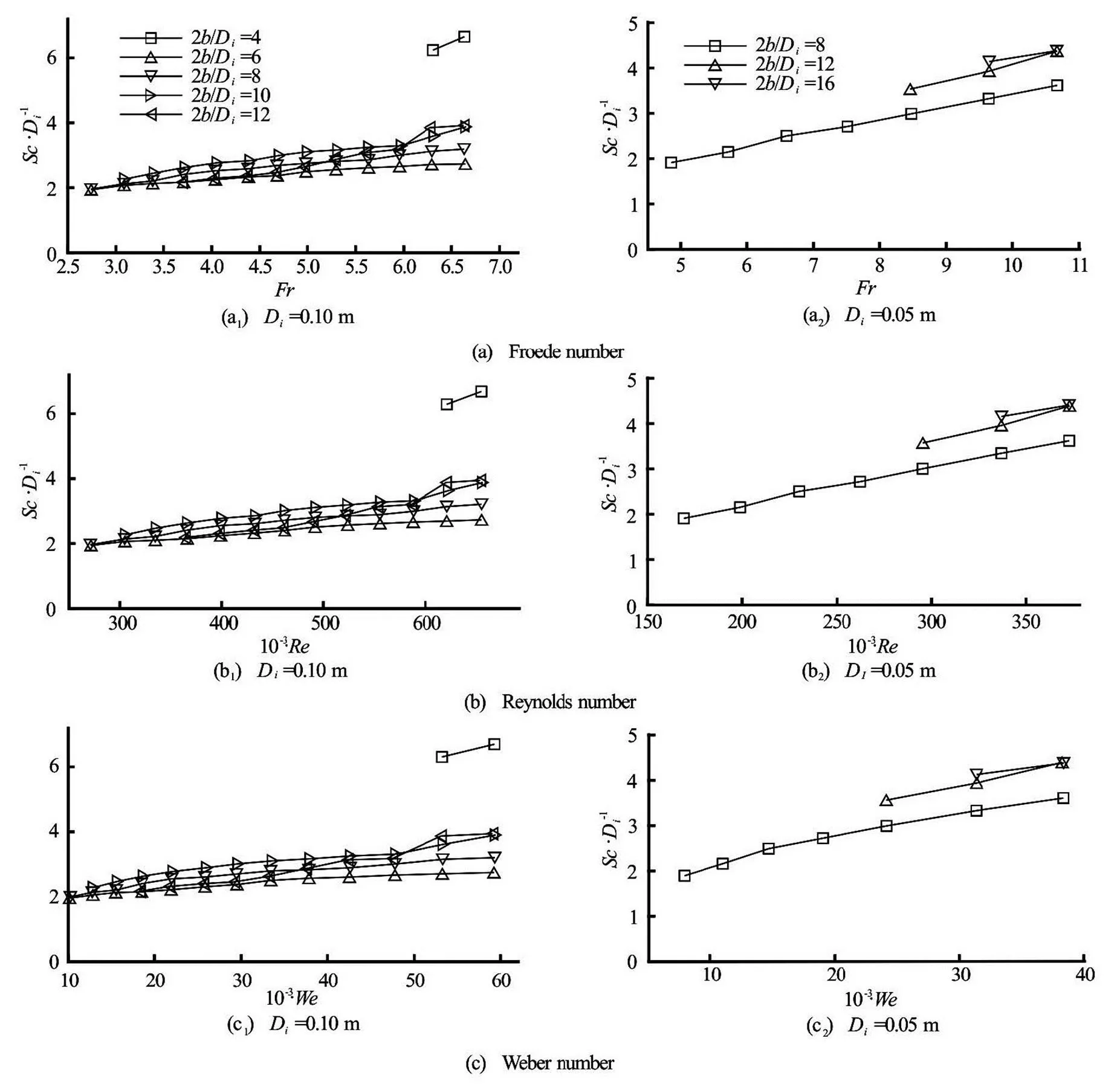

The summary of the present study in terms of the related important dimensionless parameters affecting the critical submergence are presented in Table 1[15,16]. The variation ofwith the related dimensionless parameters,,andare given in Figs.3-5 as a functionfor each pipe tested. From these figures the following assessments can be made.

Table 1 Summary of the important parameters related to the critical submergence

Fig.3 Variations of with for various values for pipes

Fig.4 Variations of for various values for pipes

Fig.5 Variations of for various values for pipes

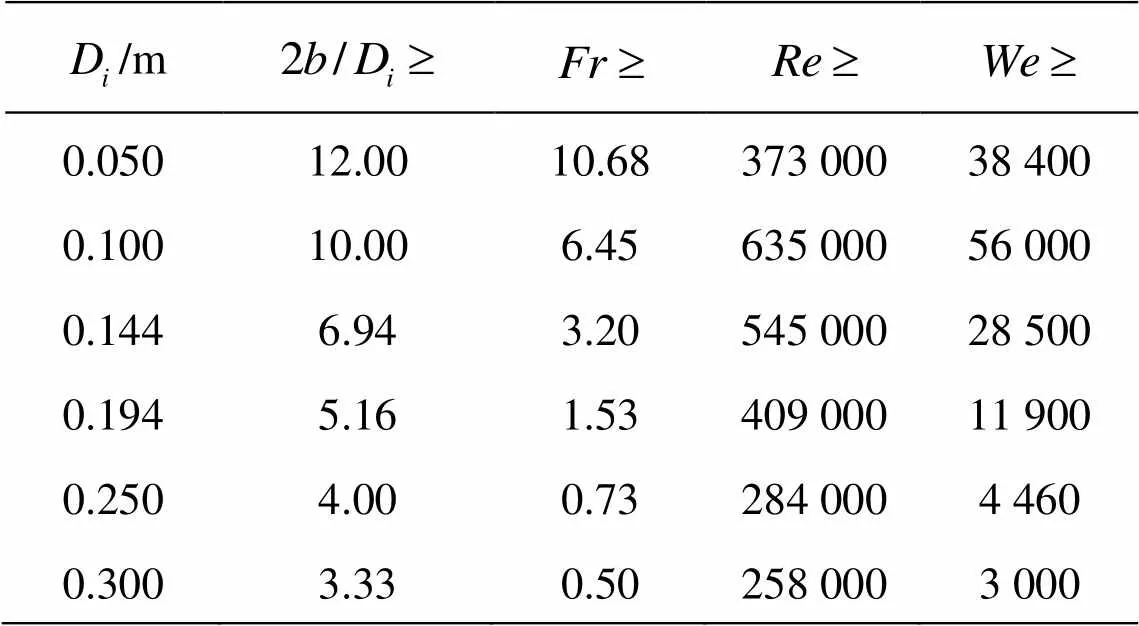

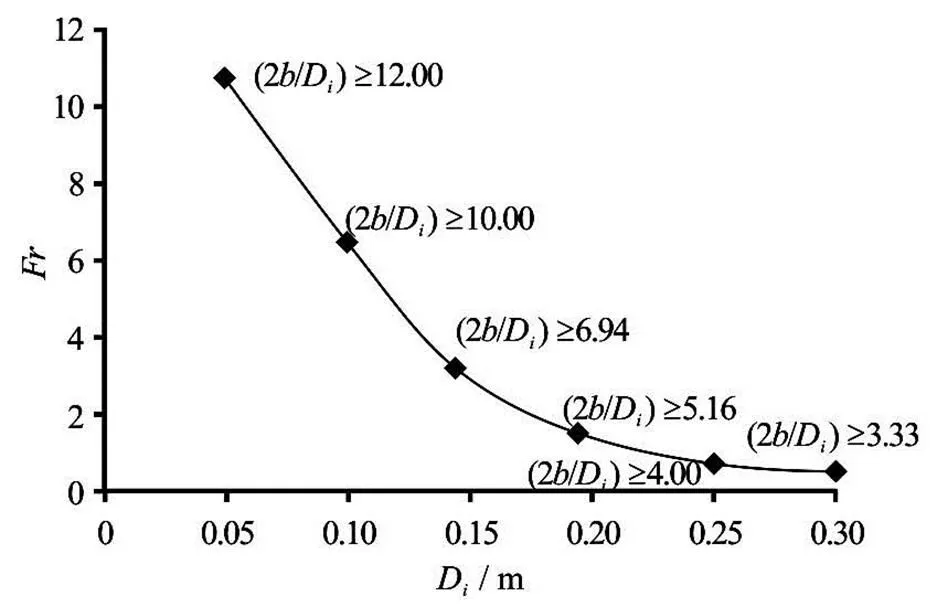

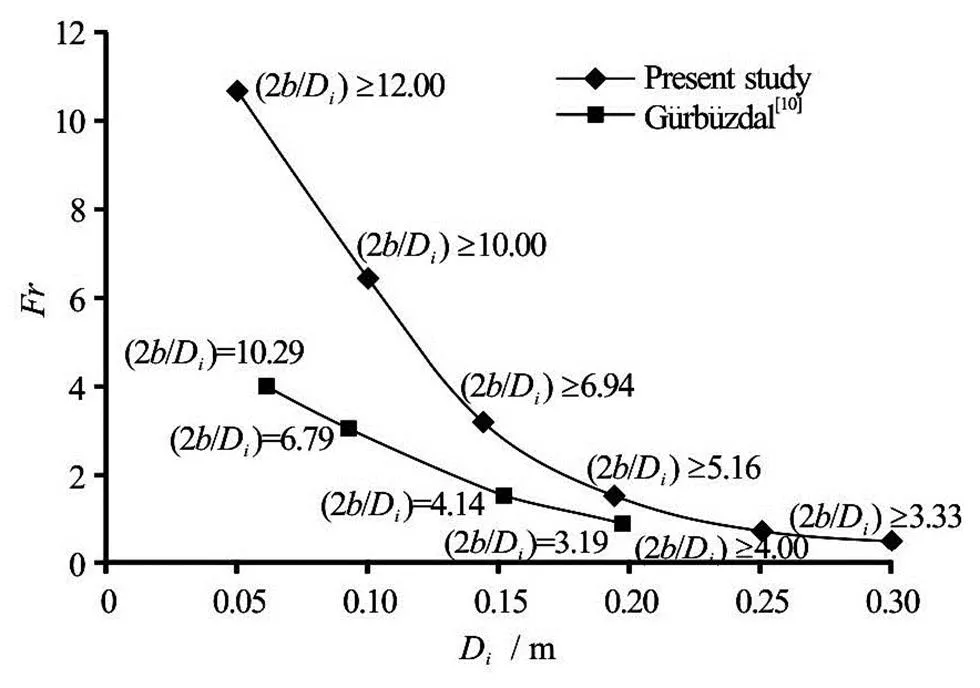

For the remaining values oftested the va- riation ofwithas a function of,andis not very significant and becomes almost negligible as the related parameter,,or, increases. The data offor these intermediate values ofcoincide with each other at the ma- ximum values of,andtested. These ma- ximum values of,,and corresponding li- miting values ofabove whichis in-dependent of, as a function of intake diameter ofwere determined from the data of Figs.3-5 and listed in Table 2. From Table 2, Fig.6 which shows the limit values ofwas prepared and plotted. Ac- cording to Fig.6,is independent of the side wall clearance as long asvalues are larger than those stated on the figure for a given intake pipe dia- meter, and is only function of,andifis larger than those corresponding values given on the figure (the limit values of other parameters,and, are not given on the figure). The area below the curve given in Fig.6 belongs to a zone whereis a function ofand, while in the area above the curve whereis larger than that stated on the curve,is independent ofand fun- ction offor an intake of known. This figure also reveals another important information for the in- take pipes of larger diameters not tested in this study. From the general trend of the curve, it can be conclu- ded that as the intake pipe diameter gets larger than 0.3 m, the rate of change ofwithgets smaller and maybe approaches to zero at much higher values of. At the same time, at largervalues, the limit values forand, above whichwill be independent of, get smaller than those of the intake pipe of. Table 3 showsvalues of the extreme cases which yield the maximum and minimumdata, as well as intermediatedata as a function ofandfor the intake pipes tested.

Table 2 Limit values of above which is in- dependent of as a function of , and for the intake pipe of diameter of

Table 2 Limit values of above which is in- dependent of as a function of , and for the intake pipe of diameter of

/m 0.05012.0010.68373 00038 400 0.10010.006.45635 00056 000 0.1446.943.20545 00028 500 0.1945.161.53409 00011 900 0.2504.000.73284 0004 460 0.3003.330.50258 0003 000

Fig.6 Limit values of above which is indepe- ndent of and function of , and

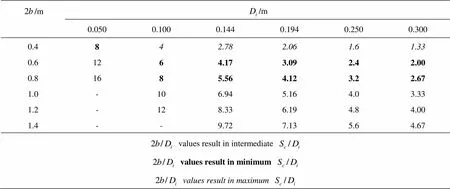

Table 3 values of the intake pipes of resulted in maximum, minimum and intermediate

Table 3 values of the intake pipes of resulted in maximum, minimum and intermediate

/m/m 0.0500.1000.1440.1940.2500.300 0.4842.782.061.61.33 0.61264.173.092.42.00 0.81685.564.123.22.67 1.0-106.945.164.03.33 1.2-128.336.194.84.00 1.4--9.727.135.64.67 values result in intermediate values result in minimum values result in maximum

3.1

Based on the information of Table 3, these three groups are treated separately and the empirical equa- tions for dimensionless critical submergence were provided. In order to determine the equation of the best fit curve to the data ofas a function of,,andconsidering Eq.(3), various types of empirical equations were tested by using regression analysis. Finally, the type of equation given in Eq.(4) was found to be the one having the highest correlation coefficient.

The derived equations for the maximum, mini- mum and intermediatevalues are as follows

Equation (5) was derived from thedata of smallvalues tested in the study and results in largevalues which are not desired in practical applications. Equation (7) gives intermediatevalues and corresponds to largevalues. In this zone,values become almost independent ofafter certain limit values ofas a function of intake diameter used. Therefore, this equation can be preferred in the design of intakes. As for Eq.(6), it yields the smallestvalues but theirva- lues are not as large as those of the intermediate zone and even at large,is function of.

In order to see the effect of,andon the value of, these terms were excluded in a row from Eq.(7) and the regression analysis was app- lied to the available intermediate data and the follo- wing equations were derived.

From the correlation coefficients and error per- centages of the equations given above, it can be con- cluded that as the related dimensionless terms,and, are dropped from the initial general equation, the error in the calculation ofwill in- crease slightly.

Finally, if only the limiting data values given on the curve of Fig.6 are used,values with thestated on the curve with the correspondingandfor an intake of known diameter whereis independent of, in the regression analysis, the following equations are derived:

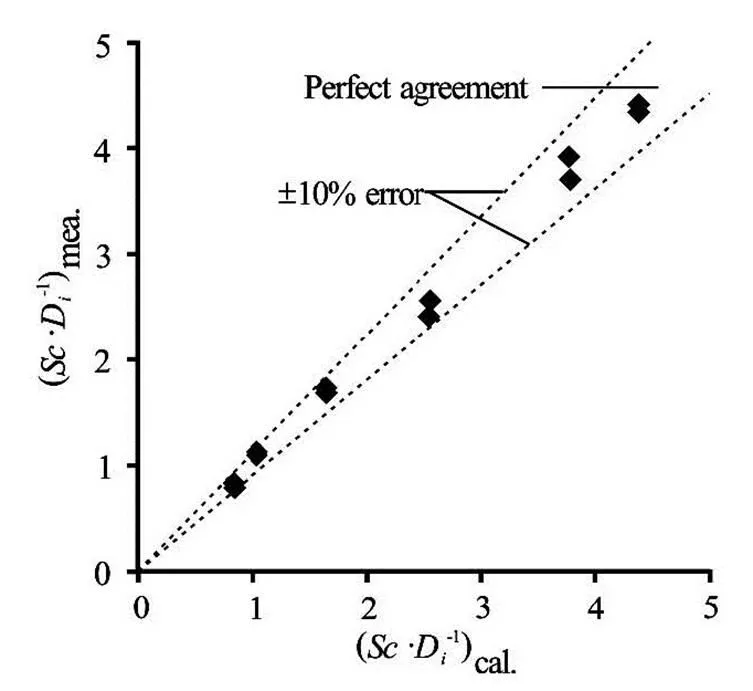

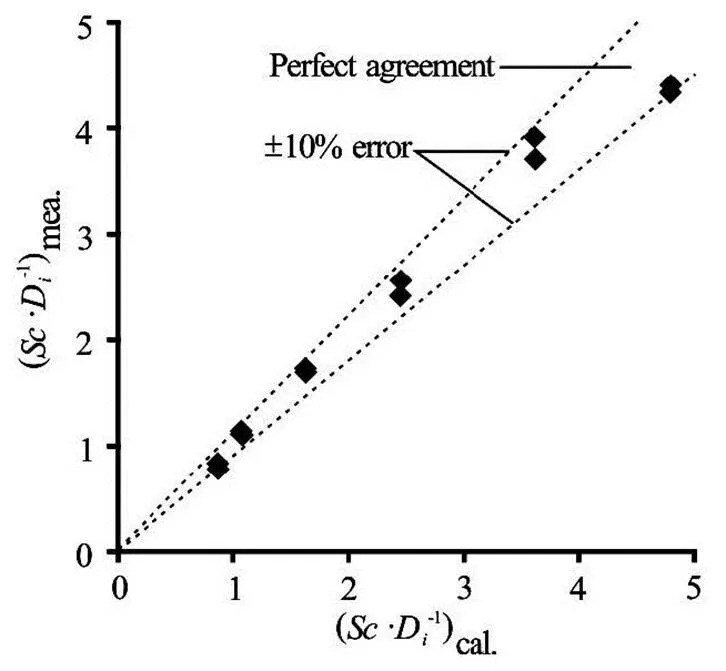

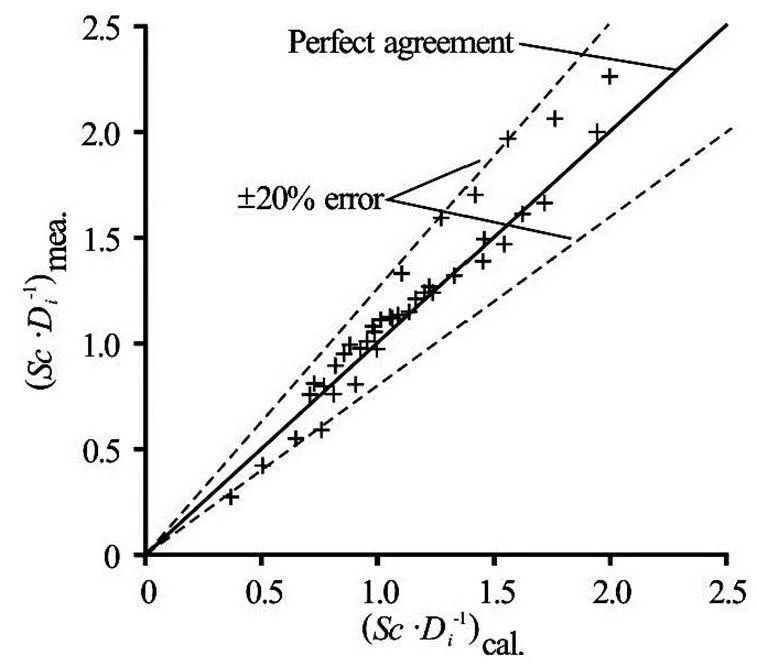

Figures 7 and 8 show the variation of the measu- red and calculatedvalues which are obtained from Eqs.(11) and (12), respectively. As the paramete- rsandare excluded from the general equation of, Eq.(11), the correlation coefficient of the new equation, Eq.(12), decreases slightly.

Fig.7 Comparison of measured and calculated values from the application of Eq.(11) to the available interme- diate data

Fig.8 Comparison of measured and calculated values from the application of Eq.(12) to the available interme- diate data

3.2

In hydraulic model studies the aim is to provide a complete similarity between the prototype and the model. In this case one can get correct prototype data directly from the measured or calculated model data. The complete similarity between the model and proto- type is satisfied if all the corresponding dimensionless parameters of the governing equation of the phenome- non are the same. In this study the governing equation is Eq.(3).

In practice it is not possible to satisfy this condi- tion because it results in model length scale of unity. Therefore in the study of small scale hydraulic models only the equality of the most important dimensionless flow property is considered. This predominant para- meter is Froude number in vortex models and it is as- sumed that the effect of the other parameters conside- ring Eq.(3), the Reynolds and Weber numbers, on the dependent dimensionless parameter,, is negli- gible. Due to this assumption it is obvious that the complete similarity between the two systems cannot be satisfied. Therefore, the measured values offrom the model cannot be directly converted into the prototype value without considering the scale effect of the model. The scale effect of a model decreases as the model length ratio decreases.

In order to find out the scale effects on the values of, the available experimental results were ana- lyzed and the pipe and flow parameters for the same Froude numbers were determined. Among these data, the ones having almost the samevalues were selected. Each pair of data for a known Froude num- ber belongs to two pipes of different diameters. The first pipe which is larger in diameter than the second pipe is considered as the prototype of the second one. In the observation of the scale effect on the dimen- sionless critical submergence, the following paramete- rs were used: model length scale, the ratio of the dimensionless critical submergence values for the model and the prototype,, the ratios of the Reynolds numbers,, and the ratios of the Weber numbers,.

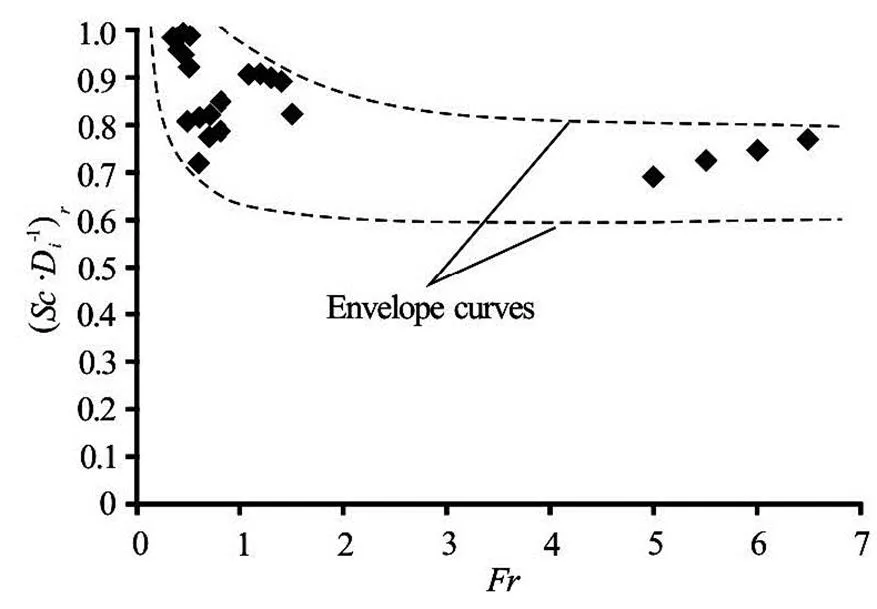

Fig.9 Variation of with Froude number

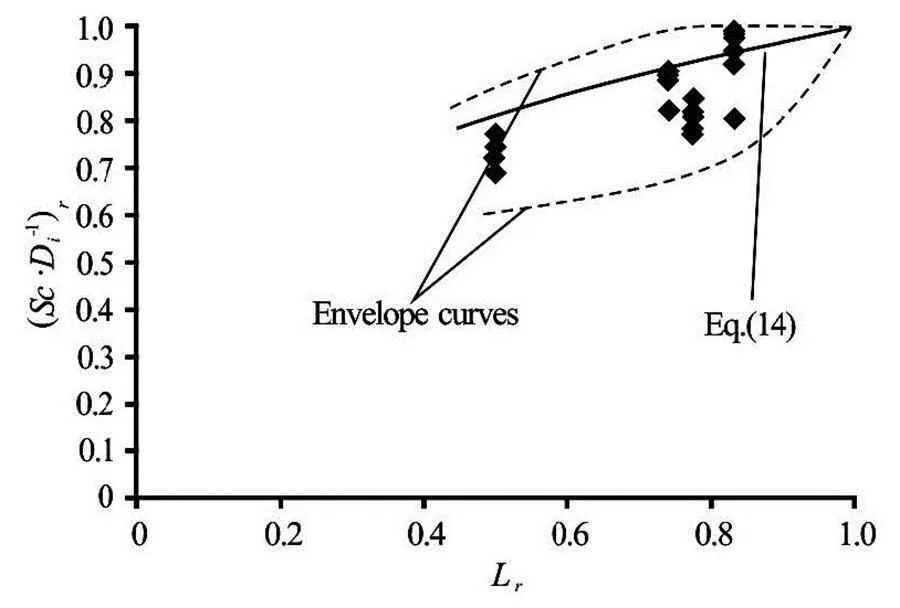

Fig.10 Variation of with

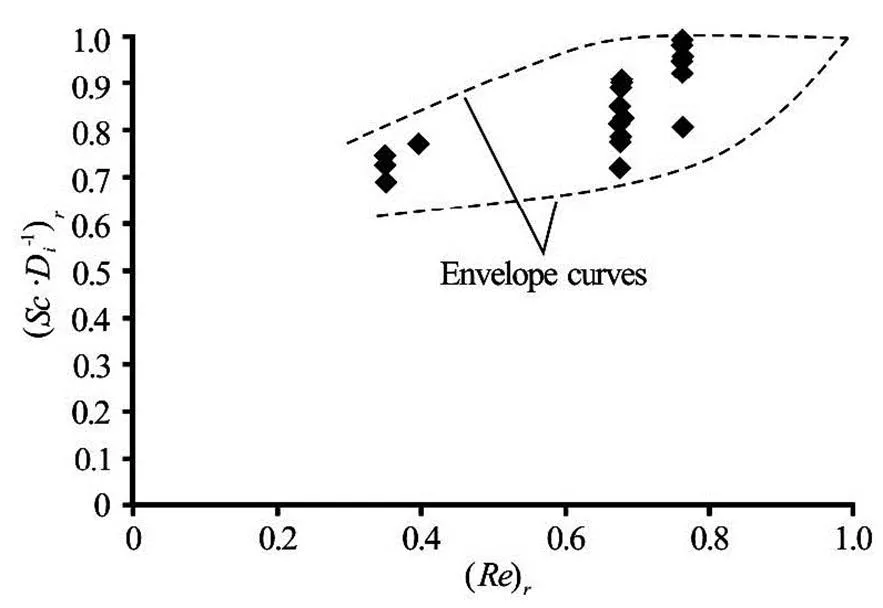

Fig.11 Variation of with

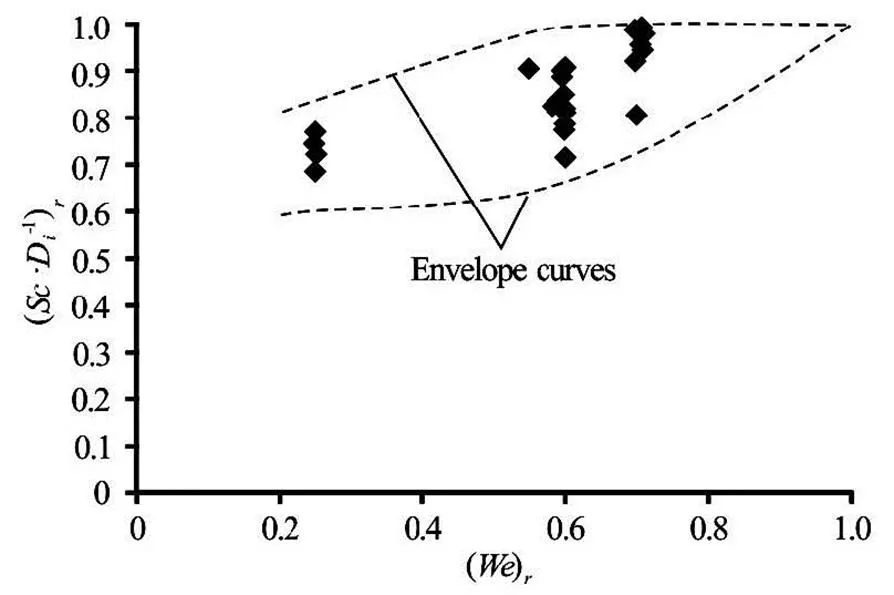

Fig.12 Variation of with

From the following argument another estimation for the calculation ofcan be made. If it is assumed that Eq.(11) is applicable to prototypes as well as models, one can write the following relation- ship for.

If Eq.(14) is plotted in Fig.10 for the zone ofwhere the test data are available, it is seen that the curve of Eq.(14) lies between the envelope curves. For a rough calculation of, Eq.(14) may be used within the zone oftested in this study. Additional experiments must be conducted at smallervalues to show that Eq.(14) is applicable or not.

In a similar way to Fig.10, Figs.11 and 12 show the variation ofwithandwith, respectively. The general trends of the data values of these figures also imply that asandincrease,increase and approach to 1.0 forand.

Finally, from the analysis of all these figures, it can be concluded that as the model scale,, gets smaller, the scale effect on the value ofbe- comes more significant.

3.3Validation of the proposed Emprical equations with the related relationships presented in Gürbüzdal’s study

Gürbüzdal[10]conducted similar experiments to those presented in this study with four pipes of diffe- rent diameters. The experiments were conducted in a similar setup with constantfor a wide range of discharges.values used in the experi- ments and the maximum Froude numbers tested with each intake pipe used are shown in Fig.13 along with the corresponding values of this study which were presented in Fig.6. From Fig.13, it is clearly seen that the data of Gürbüzdal[10]are below the curve of the present study which was named as “intermediate zone” whereis function of,,and. In order to show how well the empirical equation, Eq.(7), proposed in this study fits the data of Gürbüzdal[10], Fig.14 is plotted. In this figure, the cal- culatedvalues were determined using the re- quired values of,,andfrom the data of Gürbüzdal[10]and plotted with respect to those observed by Gürbüzdal[10]as measured. Figure 14 reveals that there is a good agreement between the proposed equation, Eq.(7), and Gürbüzdal’s[10]data which lie withinerror lines.

Fig.13 For present and Gürbüzdal[10] study, limit values of above which is independent of and function of , and

Fig.14 Comparison of measured and calculated (from Eq.(7)) intermediate values of Gürbüzdal[10]

3.4Gordon’s, Reddy and Pickford’s and Gulliver and Rindels’ studies

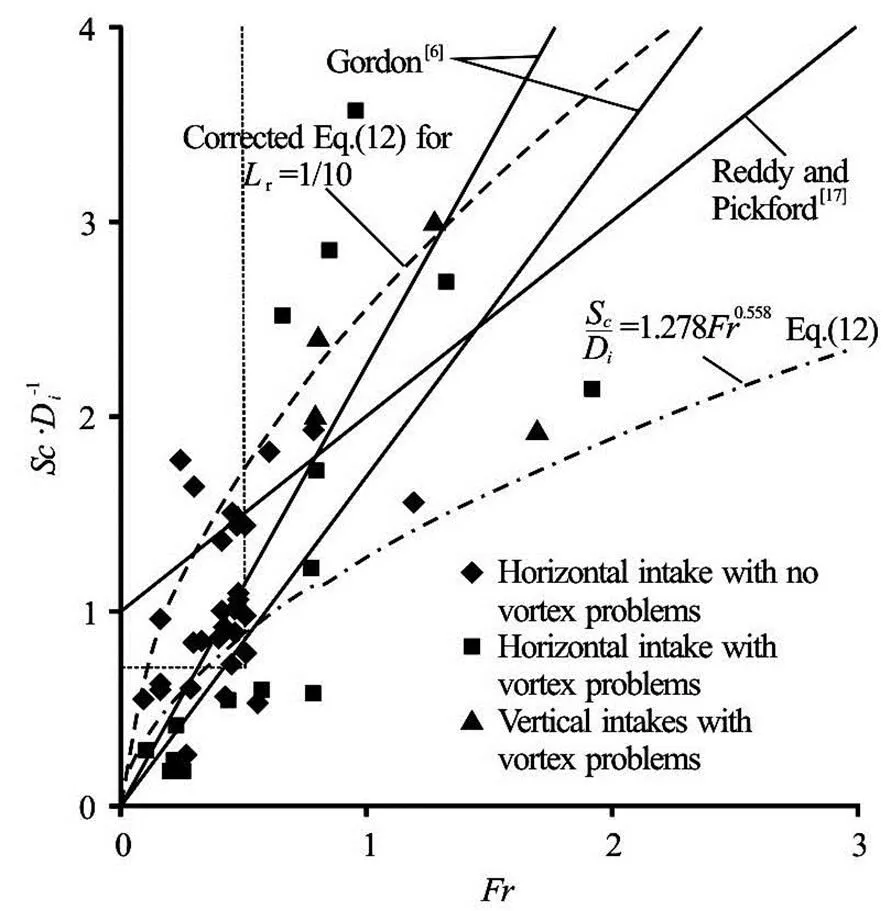

Gulliver and Rindel[18]compiled all the available data, together with Gordon[6]’s data, on existing insta- llations and model studies of proposed installations and presented it in a figure, Fig.15, to obtain the most accurate values of submergence as a function of. Two envelope curves which result from Gordon’s[6]criteria are also given in this figure. From this figure, it is seen that neither Gordon’s[6]nor Reddy and Pickford’s[17]design criteria are sufficient to avoid vortex problems. However, there is a region where free-surface vortices are less likely to occur, that is the region segmented by a dimensionless submergence,, greater than 0.7 and an intake Froude number,, less than 0.5. However, if a given intake installation has extremely poor approach flow condi- tions, vortices are still possible in this “safe” region. In order to compare the validity of Eq.(12) with the available data ofin literature, Eq.(12) was plotted into this and presented as Fig.15. The curve of Eq.(12) lies below all the other curves given in the figure. The agreement between Eq.(12) and the rela- tions of Gordon[6]is quite good for the Froude number up to about 0.6. For larger Froude numbers, Eq.(12) estimates much lowervalues than the others. Large Froude numbers were achieved in the present study by using mostly pipes of small diameters. Whereas, most of the data presented in Fig.15 were provided from the existing installations. Therefore, the data of the small diameter pipes used in the present study represent only the data of small scale models, from which one cannot directly convert the model data to the prototype values. The scale effects due to neglecting the similarity of,and probably the wall clearance, are the reasons for not having a good agreement between the model data and prototype data.

Fig.15 Dimensionless plot of the data obtained from the existi- ng intakes, field installations and model studies[18] with the relationships proposed by Gordon[6], Reddy and Ve Pickford[17], Eq.(12) and corrected Eq.(12) for 1/10

As a rough estimation, if it is assumed that the experimental setups tested in this study were models of the prototypes, with a length scale of, from Eq.(14), the value ofis calculated as 0.5, from which. This means that, if the validity of Eq.(14) is assumed for a model of, the critical submergence of the proto- type may be selected as twice the corresponding model value. In the light of this informationvalues of Eq.(12) can be multiplied by 2 to determine thevalues to be expected in the prototype which are shown in Fig.15 as “corrected Eq.(12)” for this specific example. As it is seen from the figure, the curve of the “corrected Eq.(12)” lies above most of the data having vortex problems.

4. Conclusions

In the present study the effects of the Froude, Reynolds, Weber numbers and side wall clearance on the formation of air-entraining vortices at horizontal intakes were investigated experimentally. Empirical equations for dimensionless critical submergence,, were derived from the experimental data as a fun- ction of the relevant dimensionless parameters and the validity of them was checked with the other data in the literature. Considering the model-prototype con- cept, the available data were analyzed and the scale effect on the values of dimensionless critical submer- gence was investigated. From this experimental study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(4) As a function of intake pipe diameter, there are limit values for,,andabove whichis independent ofand function of,and.

(5) For all three cases described above, yielding maximum, minimum and intermediatevalues as a function of, and for only limit values of,and, several empirical equations were derived forwith quite high correlation coeffi- cients.

(6) Due to the significant scale effects,values to be obtained from model studies should be multiplied by a correction coefficient before calcula- ting the correspondingvalues of the prototype directly from the length scale of the model. As the model length scale,, decreases, the value of the co- rrection coefficient increases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the TUBITAK (The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey) (Grant No. 110M676), which is gratefully ac- knowledged here.

References

[1] KNAUSS J. Swirling flow problems at intakes (Hy- draulic structures design manual)[M]. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: A. A. Balkema, 1987.

[2] CHANG Yu-chi, HU Chin-ning and TU Jing-chin et al. Experimental investigation and numerical prediction of cavitation incurred on propeller surfaces[J]. Journal of Hydrodynamics, 2010, 22(5Suppl.): 764-769.

[3] BORGHEI S. M., KABIRI-SAMANI A. R. Effects of anti-vortex plates on critical submergence at a vertical in- take[J]. Scientia Iranica, 2010, 17(2): 89-95.

[4] KABIRI-SAMANI A. R., BORGHEI S. M. Effects of anti vortex plates on air entrainment by free vortex[J]. Scientia Iranica, 2013, 20(2): 251-258

[5] SARKARDEH H., ZARRATI A. R. and ROSHAN R. Ef- fect of intake head wall and trash rack on vortices[J]. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 2010, 48(1): 108-112.

[6] GORDON J. L. Vortices at intakes[J]. Water Power, 1970, 22(4): 137-138.

[7] JIMING M., YUANBO L. and and JITANG H. Minimum submergence before double-entrance pressure intakes[J]. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, ASCE, 2000, 126(8): 628-631.

[8] LI Hai-feng, CHEN Hong-xun and MA Zheng et al. Expe- rimental and numerical investigation of free surface vor- tex[J]. Journal of Hydrodynamics, 2008, 20(4): 485-491.

[9] AHMAD Z., RAO K. V. and and MITTAL M. K. Critical submergence for horizontal intakes in open channel flows[J]. Journal of Dam Engineering, 2008, 19(3): 169- 184.

[10] GüRBüZDAL F. Scale effects on the formation of vor- tices at intake structures[D]. Master Thesis,, Ankara, Turkey: Middle East Technical University, 2009.

[11] TA?TAN K., YILDIRIM N. Effects of dimensionless pa- rameters on an air-entrainig vortices[J]. Journal of Hy- draulic Research, 2010, 48(1): 57-64.

[12] TA?TAN K., YILDIRIM N. Effects of Froude, Reynolds, and Weber numbers on an air-entrainig vortex[J]. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 2014, 52(3): 421-425.

[13] YILDIRIM N., EYüPO?LU A. S. and TA?TAN K. Criti- cal submergence for dual rectangular intakes[J]. Journal of Energy Engineering, 2012, 138(4): 237-245.

[14] ANWAR H. O., WELLER J. A. and AMPHLETT M. B. Similarity of free-vortex at horizontal intake[J]. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 1978, 16(2): 95-105.

[15] BAYKARA A. Effect of hydraulic parameters on the formation of vortices at intake structures[D]. Master Thesis, Ankara, Turkey: Middle East Technical University (METU), 2013.

[16] GOGUS M., KOKEN M. Formation of vortices at water intake structures and determination of devices to eliminate them[R]. Turkish Science Foundation Report No:110M676, 2013.

[17] REDDY Y. R. VE PICKFORD J. A. Vortices at intakes in conventional sumps[J]. Water Power, 1972, 24(3): 108- 109.

[18] GULLIVER J. S., RINDELS A. J. An experimental study of critical submergence to avoid free-surface vortices at vertical intakes[R]. St. Anthony Falls Laboratory, Univer- sity of Minnesota, Project No. 224, 1983.

* Biography: Mustafa GOGUS (1952-), Male, Ph. D.,Professor

Corresponging author: Mete KOKEN, E-mail: mkoken@metu.edu.tr

10.1016/S1001-6058(16)60612-1 2016,28(1):102-113

- 水動力學(xué)研究與進展 B輯的其它文章

- Ski-jump trajectory based on take-off velocity*

- Numerical simulation of flow and bed morphology in the case of dam break floods with vegetation effect*

- Numerical study of the flow in the Yellow River with non-monotonous banks*

- Numerical and experimental studies of hydraulic noise induced by surface dipole sources in a centrifugal pump*

- Pelton turbine: Identifying the optimum number of buckets using CFD*

- Mass transport in a thin layer of power-law fluid in an Eulerian coordinate system*