Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating smoking to type 2 diabetes

Peter N Lee, Katharine J Coombs

Peter N Lee, Katharine J Coombs, Department of Statistics, P.N.Lee Statistics and Computing Ltd., Sutton SM2 5DA, Surrey, United Kingdom

Abstract

Key words: Smoking; Type 2 diabetes; Prospective studies; Meta-analyses; Doseresponse; Review

INTRODUCTION

Panet al[1], 2015 published a meta-analysis and systematic review of the relationship of active, passive and quitting smoking with incident type 2 diabetes.Based on 88 prospective studies, they reported pooled relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) compared to never smoking of 1.37 (95%CI:1.33-1.42) for current smoking, 1.14 (95%CI:1.10-1.18) for former smoking and 1.22 (95%CI:1.10-1.25) for passive smoking, and evidence of a dose-relationship with amount smoked and years quit.This was an update of a previous review by the US Surgeon General, 2014[2],which based on 46 studies, had argued for a causal relationship.As evidence on tobacco smoking and type 2 diabetes has accumulated rapidly in the last few years,we wanted to investigate more extensively how this relationship may vary based on characteristics of the study or of the RR.We conducted our own updated review and meta-analysis, based solely on active smoking of cigarettes, with or without use of pipes, cigars or smokeless tobacco.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study inclusion criteria

Epidemiological prospective studies of populations without type 2 diabetes at baseline in which smoking was related to subsequent incidence of the disease.

The studies had to provide RR estimates for one or more defined major or doserelated smoking indices.The defined “major indices” compare ever, current or exsmokers with never smokers, or current smokers with non-current smokers, and refer to smoking of any product (cigarettes, pipes, cigars and combinations) or to smoking of cigarettes.The defined “dose related indices” concern the amount currently smoked and the duration of quitting.

Study exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded where the participants were restricted to those with diseases related to type 2 diabetes.

Literature searches

This was carried out in five steps.

Step 1 identified relevant papers from four previously published reviews of evidence from relevant prospective studies.The review in the 2014 United States Surgeon-General Report[2], presented an analysis based on 46 prospective studies,taking into account studies reported in an earlier review by Williet al[3], 2007 and adding additional studies.Since that Report, which included studies published up to 2010, two further meta-analyses have been published.That by Panet al[1], 2015 included 88 studies, all but five of those considered by the United States Surgeon-General, along with many other studies published up to May 3, 2015.Another review by Akteret al[4], 2017 was limited to studies in Japan, and also considered studies up to 2015.

Step 2, carried out on January 31, 2019, repeated the Medline searches described by Panet al[1], 2015, but with the search date restricted to January 1, 2015 onwards.

Step 3 was based on a search on our in-house reference system for papers with keywords DIABETES.

Step 4, carried out on March 1, 2019, repeated the Embase searches described by Panet al[1], 2015, with the search restricted to papers not on Medline.

Finally, Step 5 was based on reference lists of papers identified in Steps 2, 3 and 4,looking for additional potentially relevant papers published from 2015.

In Steps 2 and 4, abstracts were examined first, with full texts obtained only for papers which appeared likely to be relevant.This step was initially carried out by Coombs KJ, with a 20% check made by Lee PN.

At each step, papers (or abstracts) examined for potential relevance were only those not previously considered.

At the end of this process, a set of potentially relevant papers was obtained.Subsequently, more detailed examination of the full texts at the data entry stage revealed that some papers did not actually meet the inclusion criteria, leading to a reduction in the list of relevant papers.

Data recorded

Relevant information was entered onto a publication database and a linked RR database.

The publication database contains a record for each publication describing the following aspects:In-house reference ID of the publication; first author; publication year; location (continent/country); study name; study title; population studied;beginning and end year of baseline; end year of follow-up; length of follow-up;definition of type 2 diabetes (for both baseline exclusion and subsequent incidence)and source of diagnosis; cohort size; number of type 2 diabetes cases; age at baseline;sexes considered; races considered; definition of smoking; results available (current,former, ever, amount smoked, and years quit); details of results available for specific subsets [sex, age, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, alcohol, family history of type 2 diabetes, education, diet, and others]; and details of factors adjusted for in analyses (sex, age, BMI, physical activity, alcohol, family history of type 2 diabetes,education, diet, blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, triglycerides, waist size, and others).

The RR database holds the detailed results, typically containing multiple records for each publication.Each record is linked to the relevant publication and refers to a specific comparison.The record includes details of the publication reference ID, study name, sex, age range at baseline, length of follow-up, BMI range, definition of smoking, and smoking status of the numerator (current, former or ever), and of the denominator (never or non).Where the smoking status is former, the range of years quit is entered.The range of amount smoked is also entered.For unadjusted RR estimates, the numbers of cases and at risk (or person years) are entered for both the numerator and denominator.

For adjusted RR estimates, the RR and 95%CI are entered, taken directly from the publication, or estimated using standard methods[5], with details also entered of the factors adjusted for.

Numbers of cases and at risk, or RRs and 95%CIs, are only entered for the whole population or for subgroups defined by sex, age group or BMI group.As noted above,the availability of results by other factors is recorded in the publication database, but the detailed results have not so far been entered.Results are also only entered unadjusted for potential confounding variables and adjusted for the most confounding variables for which results were available.

All data were entered by Coombs KJ and checked by Lee PN, with any disagreements discussed and resolved.

Multiple publications for the same study

Once the data were entered, the list of publications was sorted into studies.Where the RRs from only one publication needed to be used in analysis, with the others providing no useful extra data (e.g., providing similar data for a shorter follow-up),these “other” publications were rejected, with the reasons for rejection noted.Where more than one publication from the same study provided useful data (e.g., for different aspects of smoking), one publication was nominated as the main reference for the study (typically, the publication providing the most detailed results) and others were nominated as subsidiary references.Thus, it was possible to have main,subsidiary and rejected references from the same study.Another possibility is that a publication may give a pooled analysis of several individual studies, including useful data for aspects not covered in the main publications of the separate studies.These pooled publications are also nominated as subsidiary references.

Meta-analyses

Fixed-effect and random-effects meta-analyses were conducted using the method of Fleiss and Gross, 1991[6], with heterogeneity quantified by H, the ratio of the heterogeneity chisquared to its degrees of freedom.H is directly related to the statisticI2[7]by the formulaI2= 100 (H-1)/H.For all meta-analyses, Egger’s test of publication bias[8]was included.

The major smoking indices

Meta-analyses were conducted using the available data for currentvsnever, currentvsnon, evervsnever, and formervsnever smoking.Where there was a choice of estimates for a study, preference was given to results that were for the full range of amount smoked, the longest follow-up, the most adjusted, the widest age range, and the preferred product, with preference being given, in order to results for:Cigarettes;smoking excluding exclusive pipe/cigar; smoking; and tobacco; but not exclusive cigar, pipe or smokeless tobacco.For a study of both sexes, preference was also given to separate estimates for the two sexes, if available.While in most studies, the choice of estimates was straightforward, in others it was not (e.g., between an unadjusted RR for a longer follow-up from one publication and an adjusted RRs for a shorter followup from another).Here Coombs KJ and Lee PN agreed and recorded the most relevant RR to choose (disregarding its magnitude).For a particular exposure (e.g.,currentvsnever) each study could provide only the estimate or two sex-specific estimates for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Effect estimates were derived based on all the selected RRs as well as for those subdivided by various categorical variables:Sex (male, female, and sexes combined);continent (Asia, Europe, Americas, and Oceania); publication year (before 2005, 2005-14, 2015 or later); diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (self-reported, medical data only, both);population (general, pre-diabetics only, excludes pre-diabetics); total number of adjustment factors (0, 1-5, 6-10, 11+); cohort size (< 5000, 5000-20000, > 20000); number of type 2 diabetes cases (< 500, 500-999, 1000-2000, 2001+); highest baseline age (< 60,60-74, 75+ years); length of follow-up (< 5, 5-10, > 10 years); definition of smoking[cigarettes, smoking (whether or not excluding exclusive pipe/cigar), tobacco]; and whether each of a range of different variables were adjusted for.

The dose-related smoking indices

When comparing RRs by amount currently smoked (with a reference group of never smokers) or non-smokers, or by years quit (with a reference group of never smokers),a study typically provides a set of non-independent RRs for each dose-category,expressed relative to a common base.To avoid double-counting, it is necessary to include only one in any one meta-analysis.

For amount smoked, three methods were used.One method used only for studies that reported results for two levels of amount smoked, was to compare results for 1-19 and 20+ cigs/d, the most common subdivision used.The second, used only for studies that reported results for three levels of amount smoked was to compare results for low, medium and high cigs/d regardless of the levels selected.The third involved defining a set of key values (10, 20 and 40 cigs/d) and carrying out a separate meta-analysis for each key value.For an RR to be allocated to a key value its dose category had to include that key value and no other.This method was only applied for studies reporting results by three or more levels, with all three key value results available.These methods were used for data on currentvsnever smoking, and for currentvsnon-smoking.

For years quit, two methods were used.One simply used the shortest and longest categories.The other used the key values approach with values of 3, 7 and 12 years quit.

Results by BMI

For each of the studies that reported independent RR estimates separately for different subdivisions of the population by level of BMI, estimates were made, for each smoking index for which data were available, of the ratio of the RR for highestvslowest BMI group, these ratios then also being meta-analysed.

Avoidance of overlap

When conducting meta-analyses care was taken to minimize overlap of cases.Thus,results from subsidiary papers were used only when the main paper did not provide the result required for the particular meta-analysis.Also, if an RR was available from three separate studies, and also from a combined analysis from the three studies, the individual results were preferred, only using the combined RR for a smoking index for which results were not reported in all the different studies.

RESULTS

Publications and studies identified

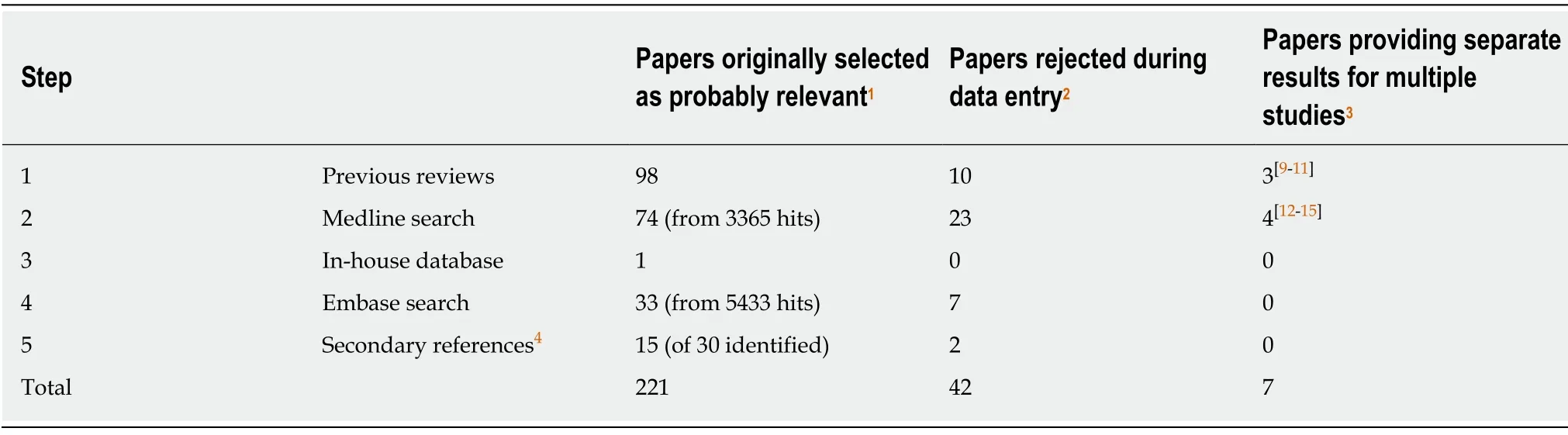

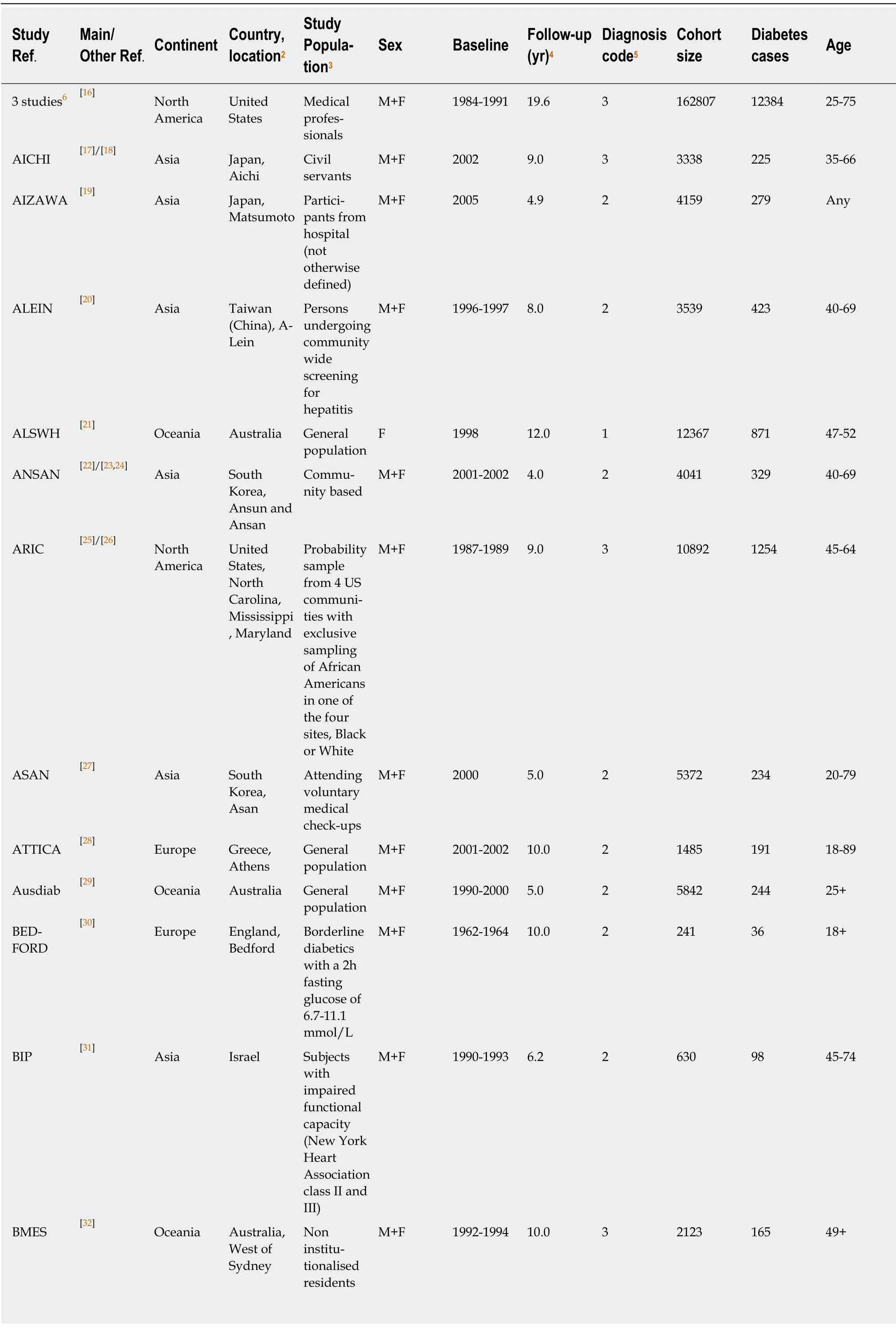

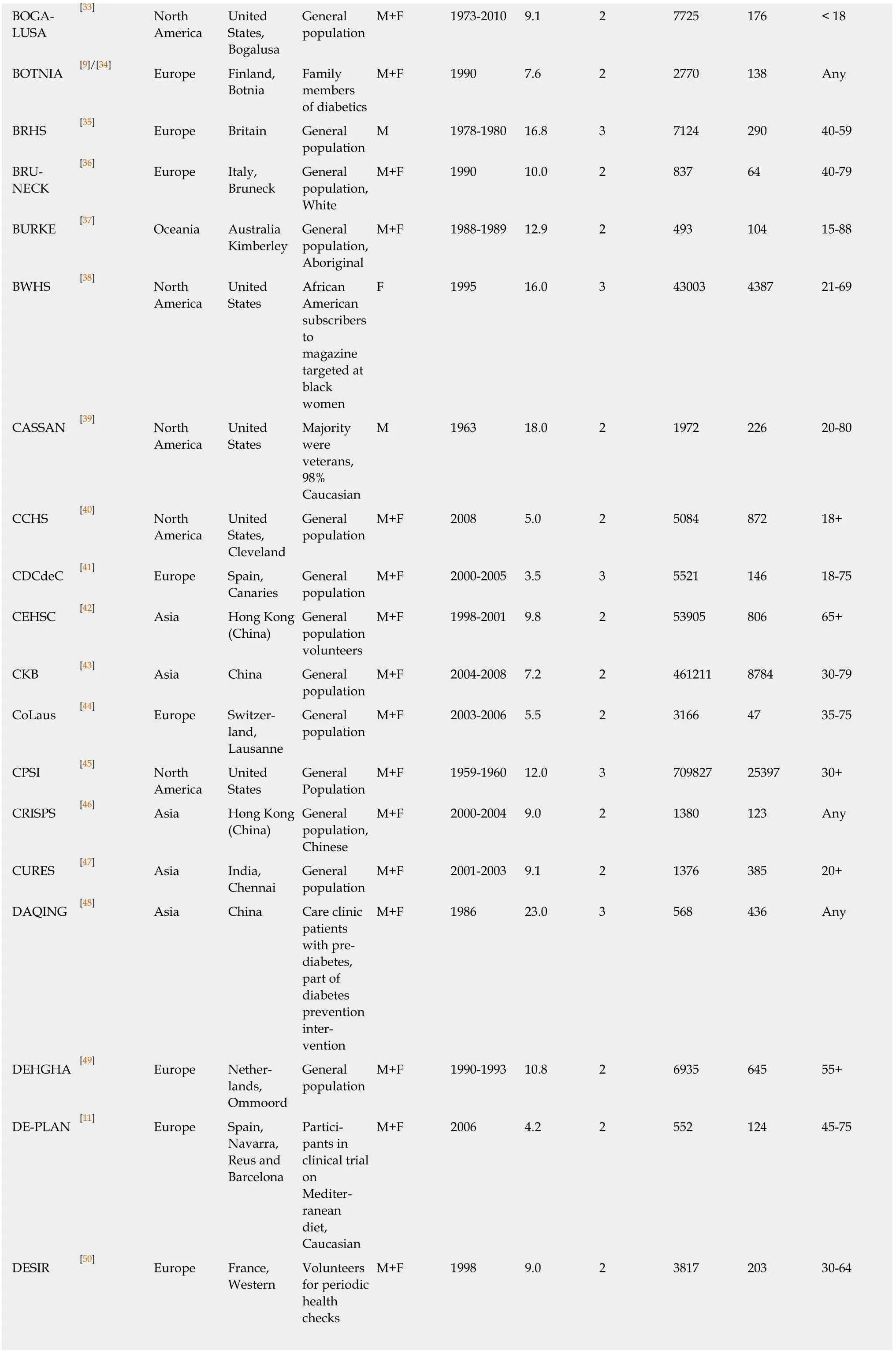

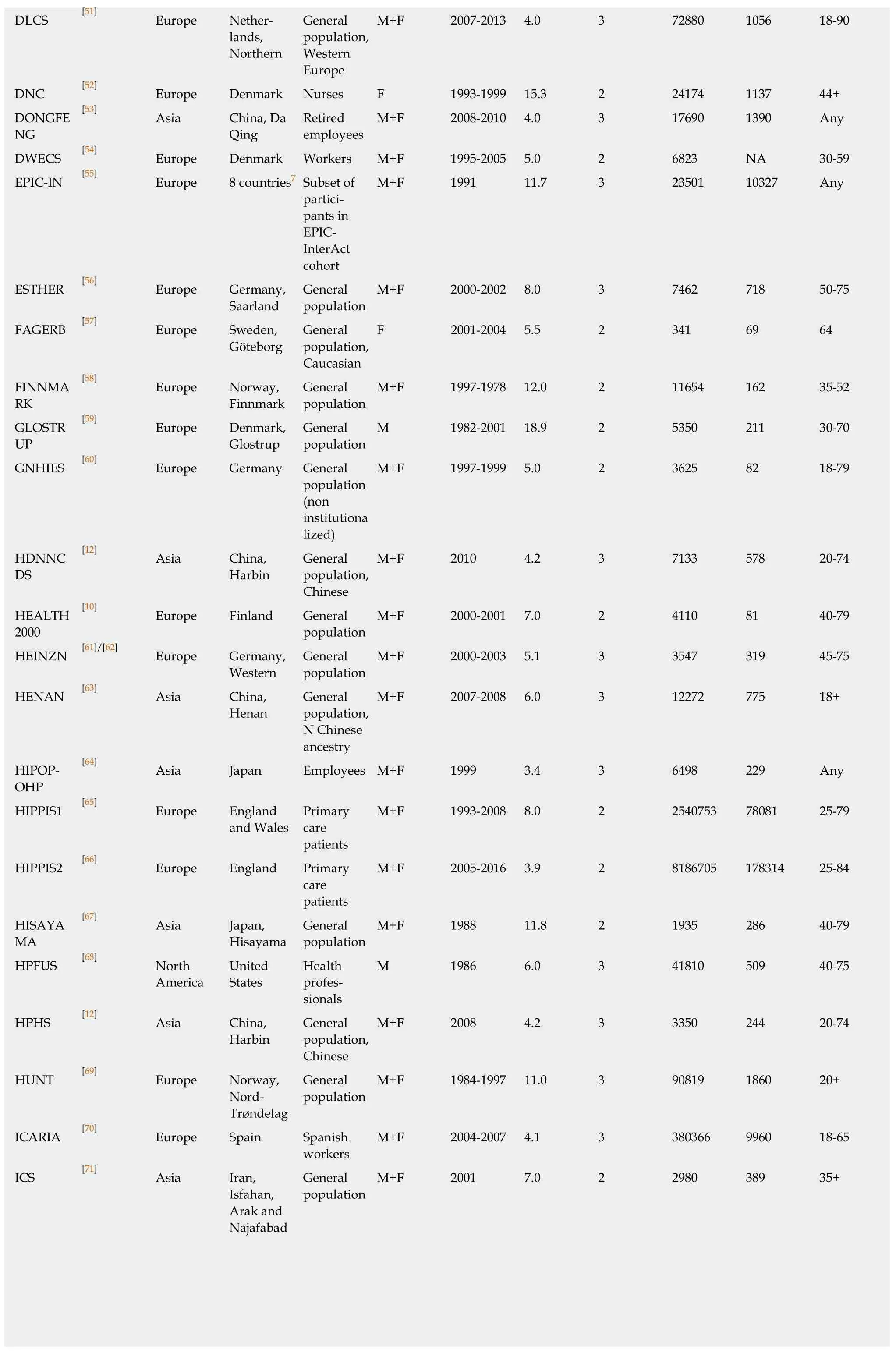

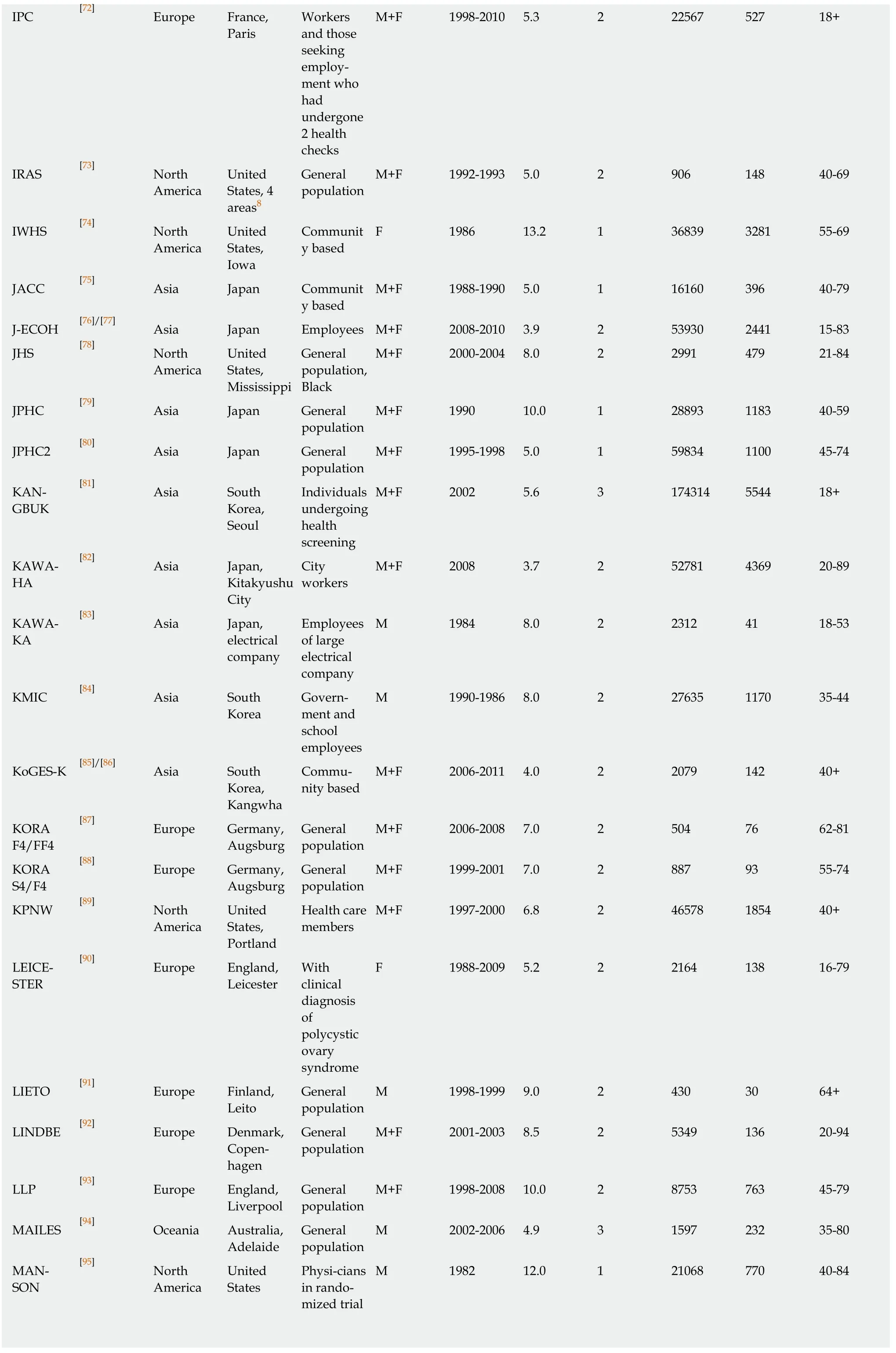

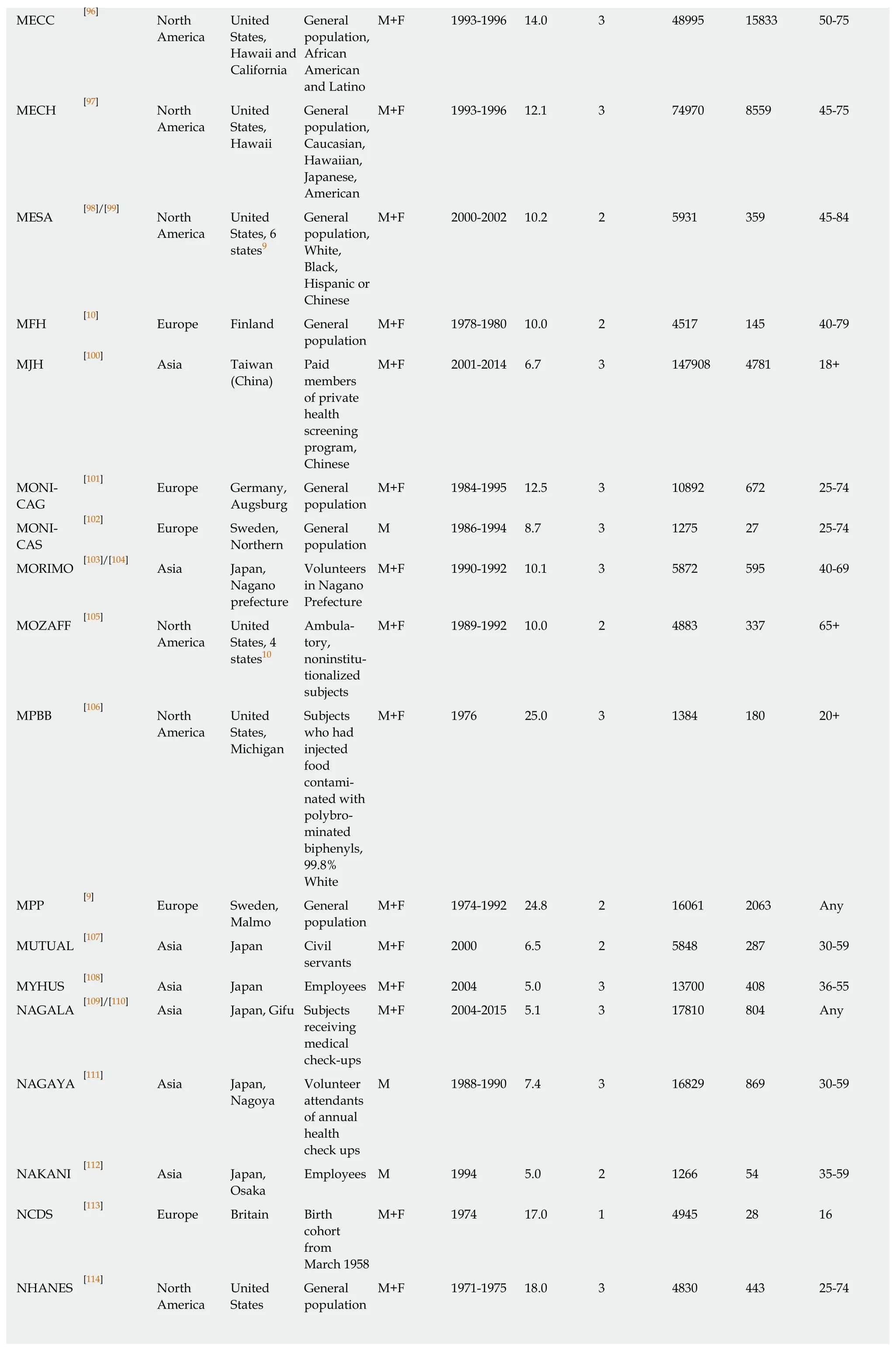

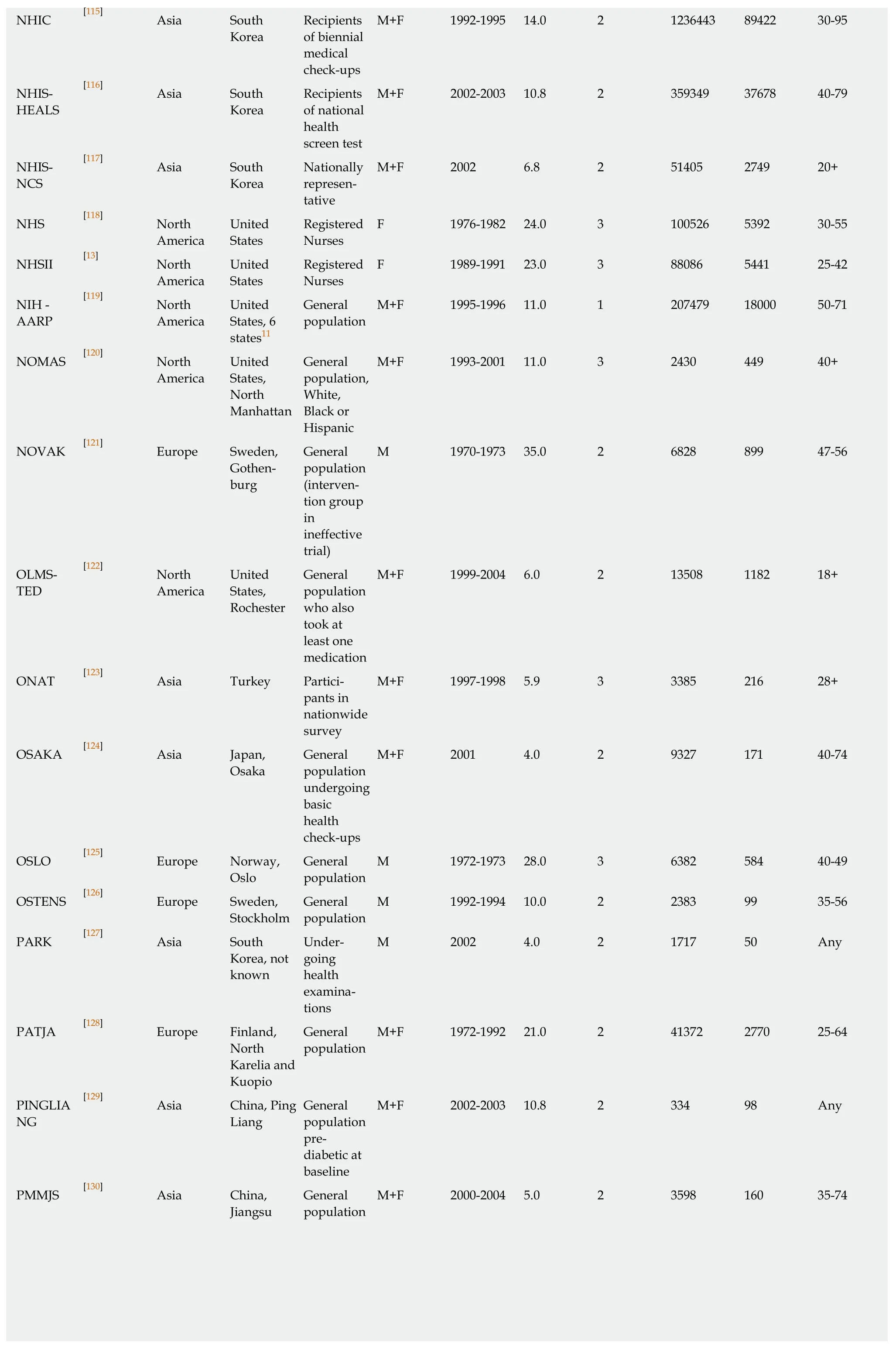

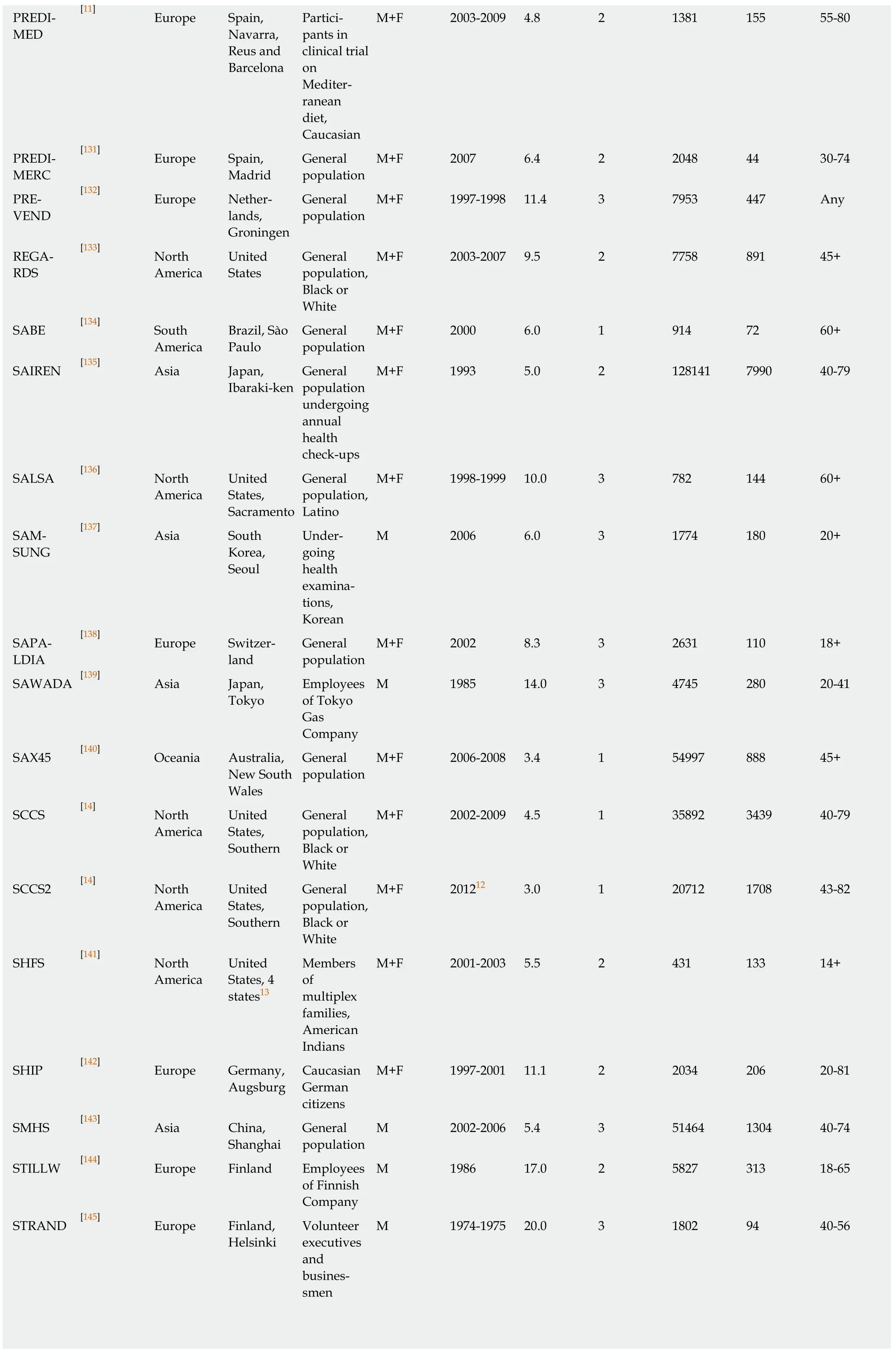

As summarized in Table 1[9-15], 221 publications were originally identified as likely to be relevant, with 42 later rejected during data entry, the reasons for rejection being given in Supplementary File 1.As seven of the publications provided results for two independent data sets (either presenting separate results for two studies or for two non-overlapping follow-up periods), data entry was carried out initially for 186 publication records.On investigation of studies with multiple records, 29 records were rejected as providing no useful information extra to those provided in other records) and 12 were classified as subsidiary, providing some limited extra information for records classified as main.This meant that there were 145 studies, 144 separate studies plus the combined analysis of three studies (HPFUS, NHS and NHSII).Table 2[9-14,16-161]summarizes some characteristics of these studies, while Supplementary file 1 also gives information on why some publications were rejected or only provided subsidiary information.

All stages of the identification of relevant papers, classification of papers with studies, and data entry were conducted initially by Coombs KJ and checked by Lee PN.Exceptionally, Lee PN only checked 20 percent of the abstracts for the Medline and Embase searches.This 20 percent check, of a total of 8798 hits, only resulted in four extra full-text papers being examined, only one of which proved to have relevant data.Given the very limited extra information obtained, and the time spent, it was decided not to extend this to a 100 percent check.

Study characteristics

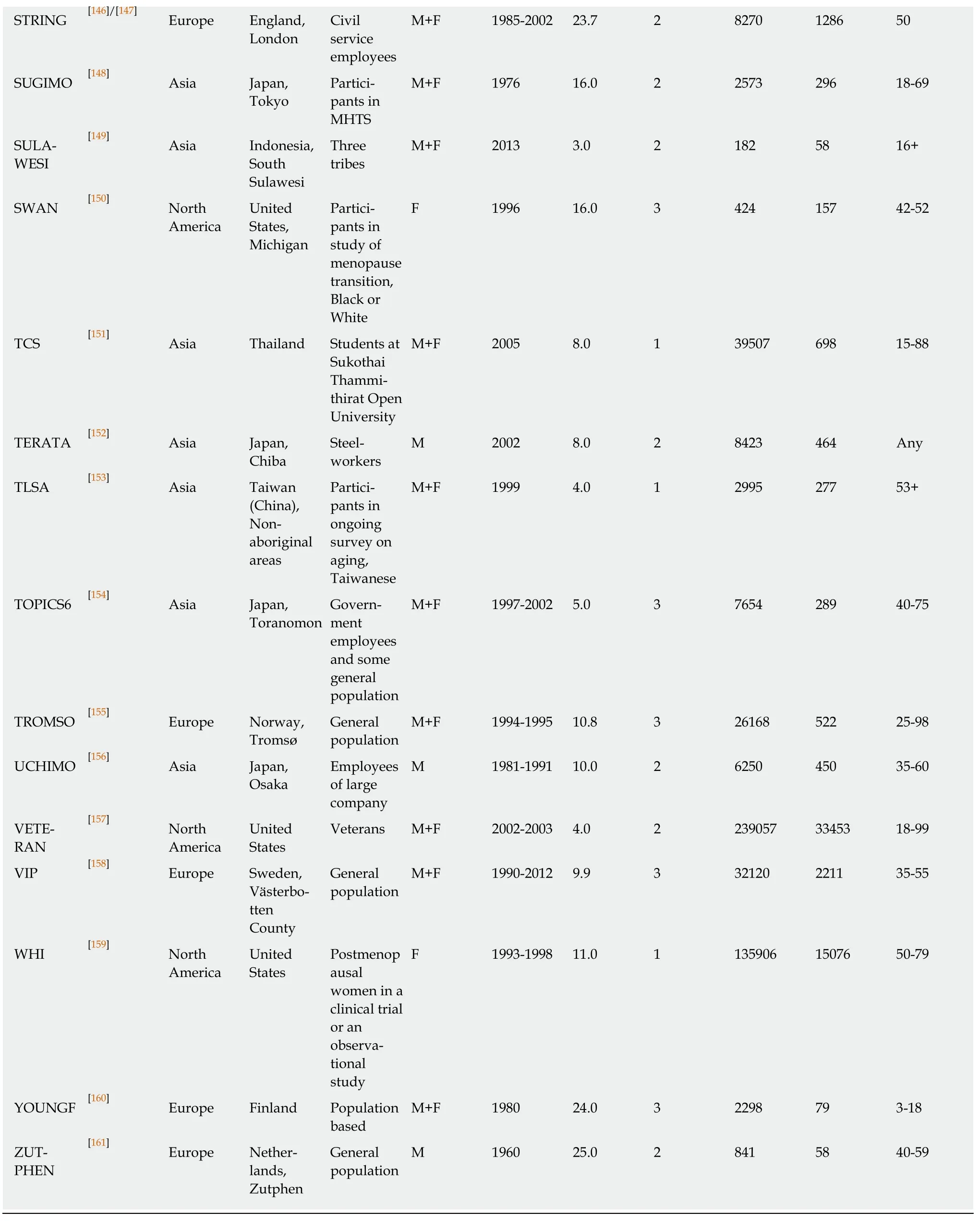

Location:As shown in Table 2, 53 of the 145 studies were conducted in Asia(including 23 in Japan, 10 in South Korea, nine in China and 11 in other countries).Fifty-three were conducted in Europe (eight in Great Britain, eight in Finland, seven in Germany, six in Sweden, five in Spain, and 19 in other countries), with 32 in North America (all in the United States), six in Australia and one in Brazil.

Population:Ten of the studies were in females, 24 in males and 111 in both sexes.About half were of the relevant general population, with Table 2 showing further details.

Time:There was a clear increase in study frequency with time, with 17 starting before 1980, 23 starting in the 1980s, 47 in the 1990s, 42 in 2000-2005, and 16 from 2006 onwards.

Years follow up:Twenty-four studies involved less than 5 years follow-up; 62 studies involved 5-9.9 years follow-up; 36 studies involved 10-14.9 years follow-up; and 23 studies involved 15 years or more years follow-up, with the longest (NOVAK)involving 35 years.

Diagnosis:Fifteen of the studies diagnosed type 2 diabetes only on the basis of selfreport of the individuals, 79 only on medical records, and 51 on both.

Size:The numbers in the cohorts studied varied from 182 to over eight million.Sixtythree were under 5000, 39 in the range 5000 to 20000 and 43 larger than this.

Type 2 diabetes cases:The number of type 2 diabetes cases varied from 27 to almost 180000.Eighty-two involved fewer than 500 cases, 21 involved 500-999 cases, 13 involved 1000-2000 cases, and 28 involved more than this.The number was not available for one study.

Age:Most of the studies included some individuals of age 75 or older at baseline.However, 24 were restricted to those aged less than 60 and 30 more were restricted to those aged less than 74.

Table 1 Literature searching

Meta-analyses

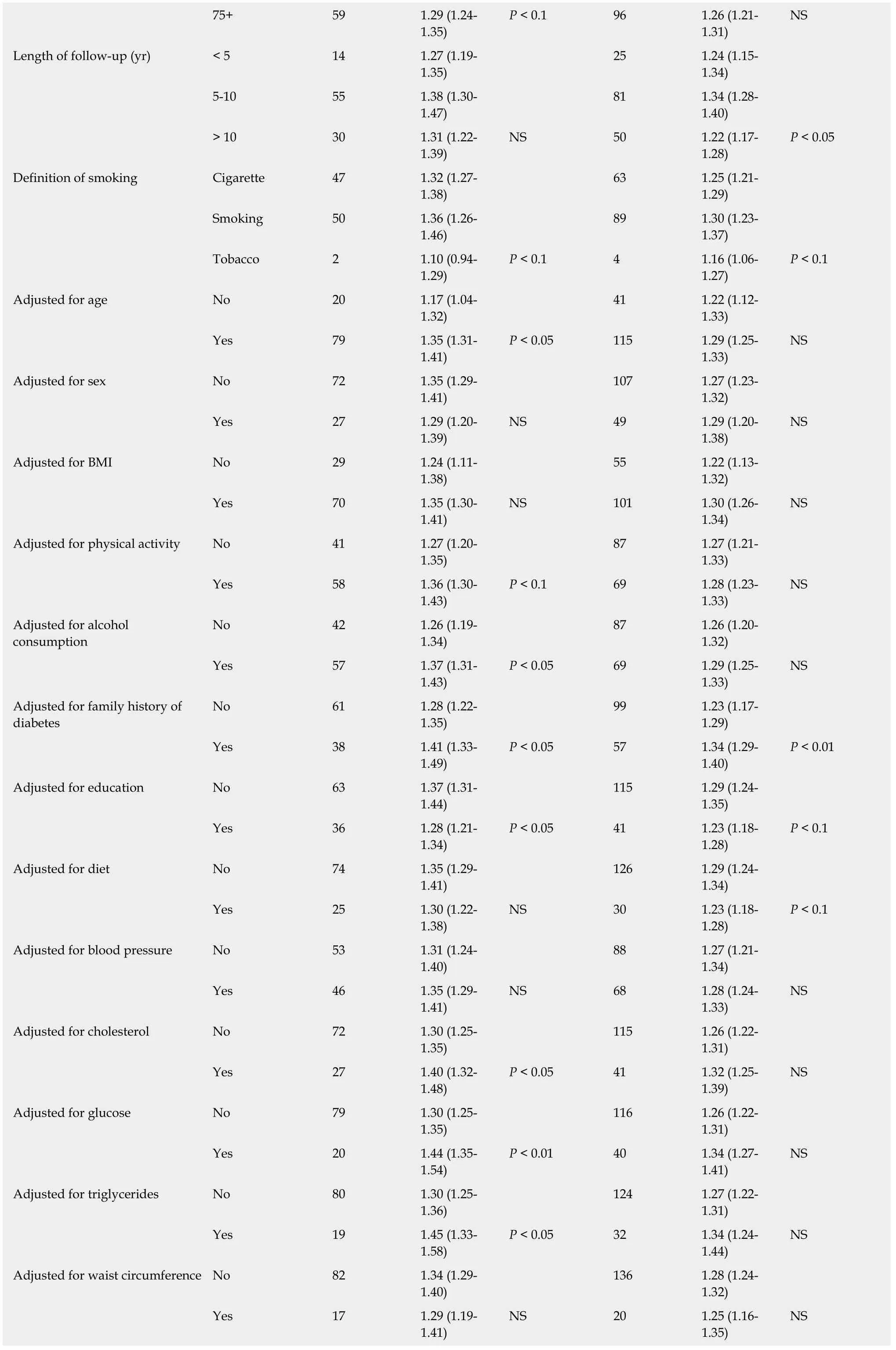

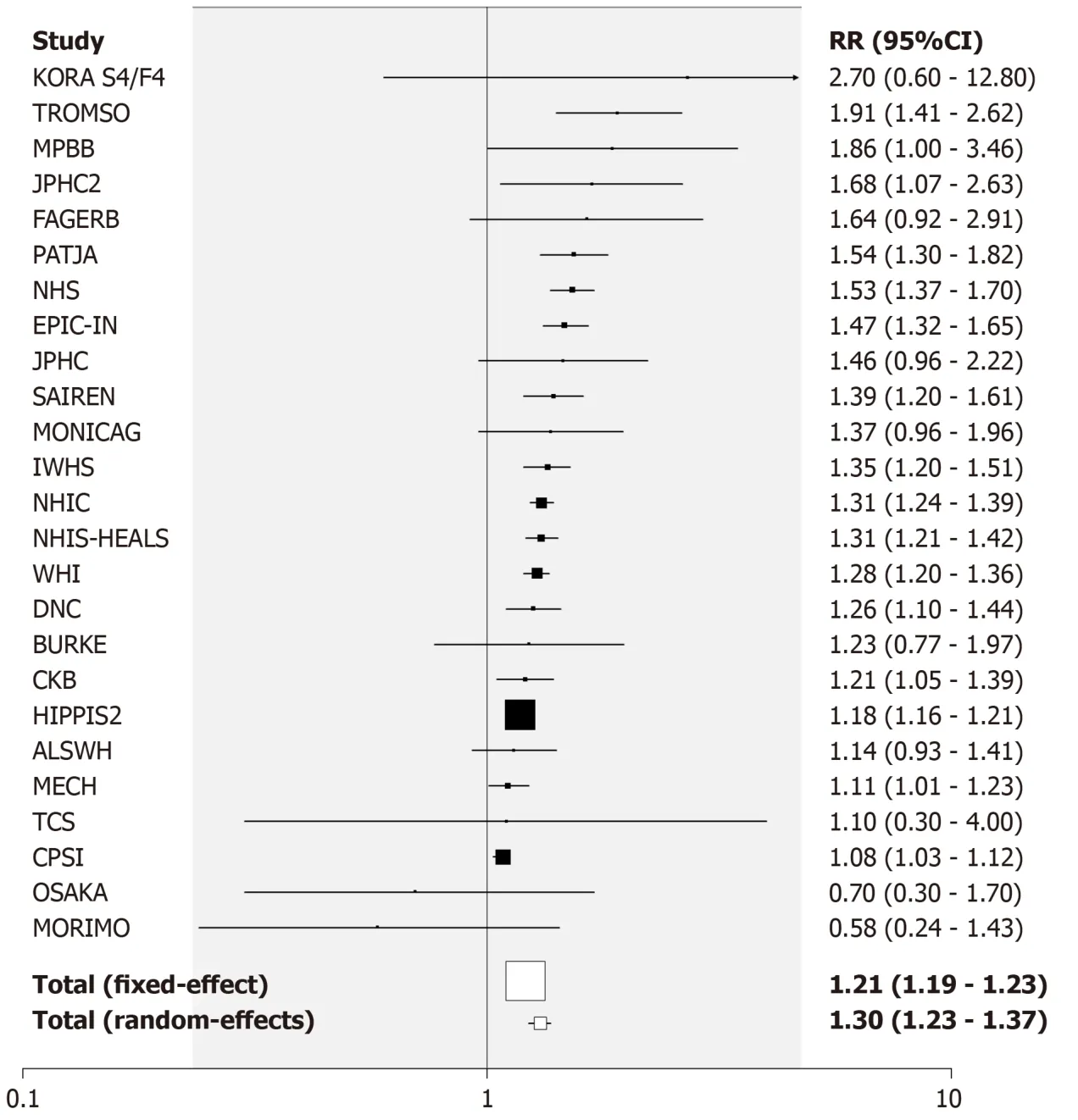

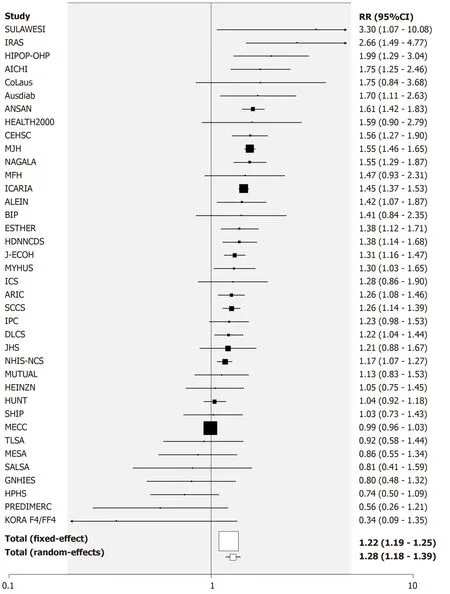

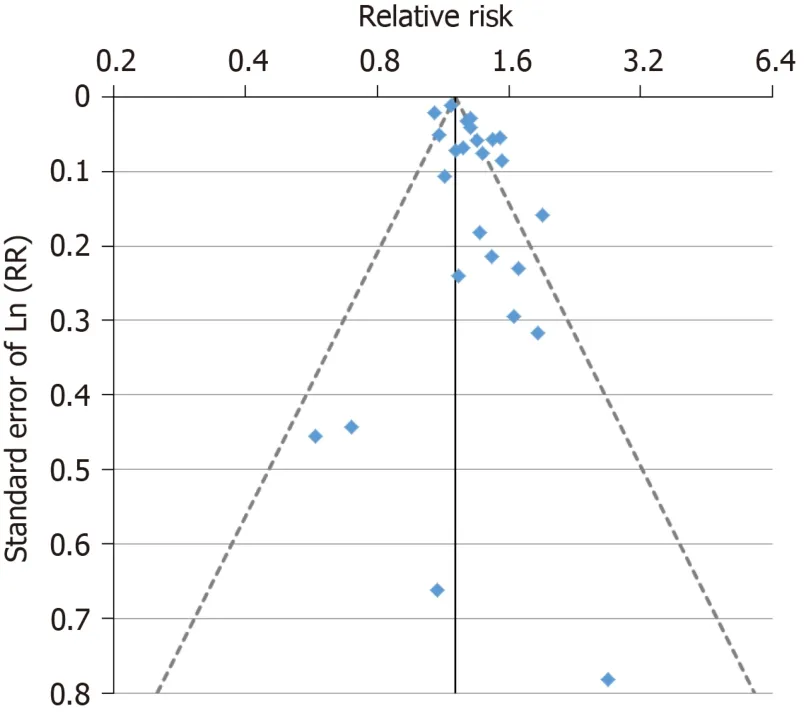

Current vs never smoking:The studies provided 99 RR estimates from 80 studies for the comparison of currentvsnever smoking.Nineteen studies provided estimates for both sexes, six for females only, 17 for males only and 38 only for sexes combined.Of the 99 estimates, 12 were below 1, 10 were above 2, with the remaining 77 in the range 1 to 2.The overall fixed-effect RR estimate was 1.25 (95%CI:1.24-1.26) with highly significant heterogeneity between the estimates (Chisq.816.8 on 98 df,P< 0.001,I2=88.0%).The random-effects estimate was somewhat higher at 1.33 (95%CI:1.28-1.38).There was limited evidence of publication bias (0.01 <P< 0.05).

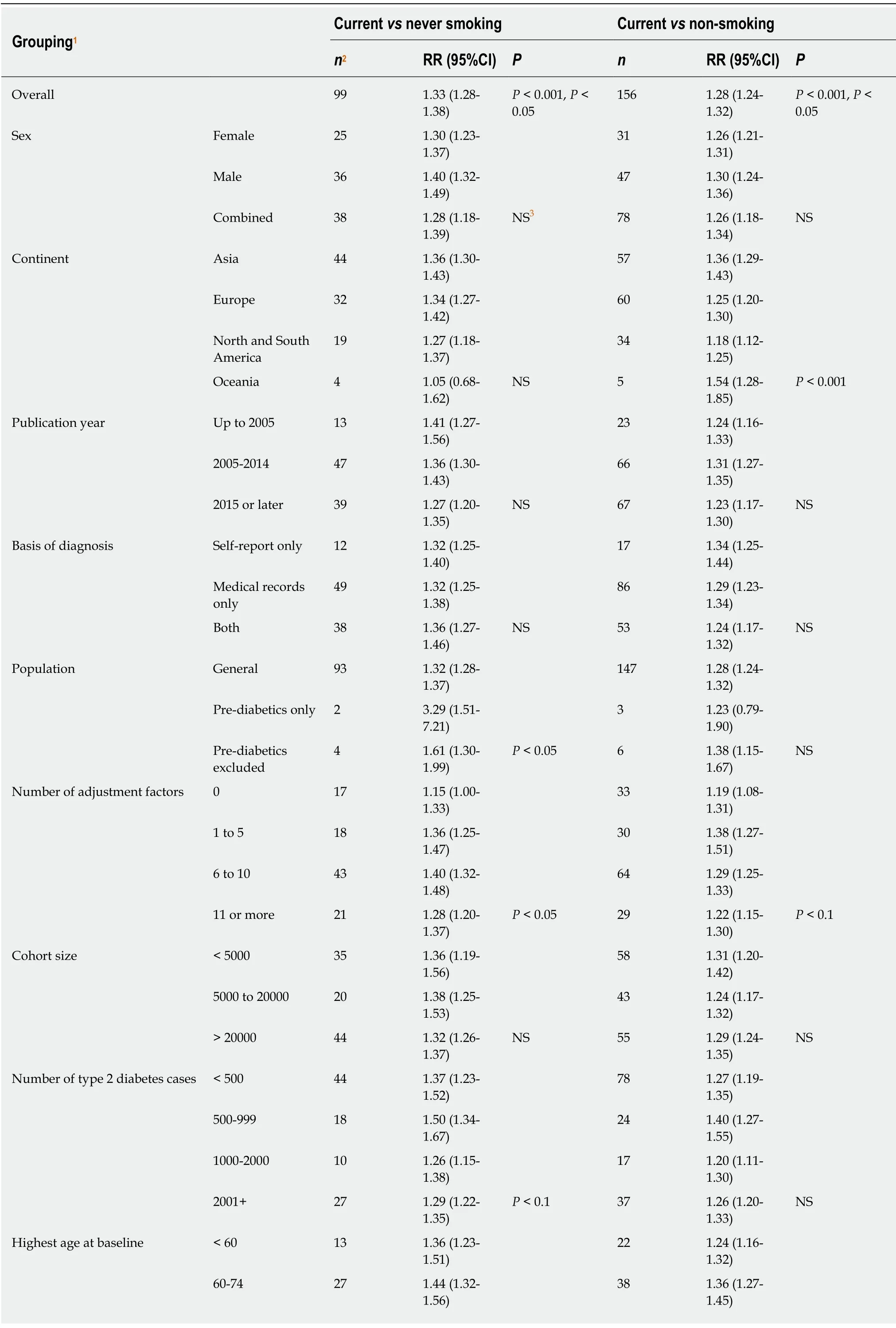

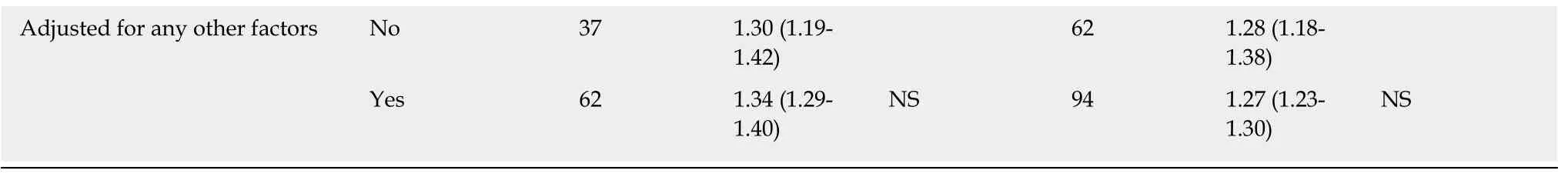

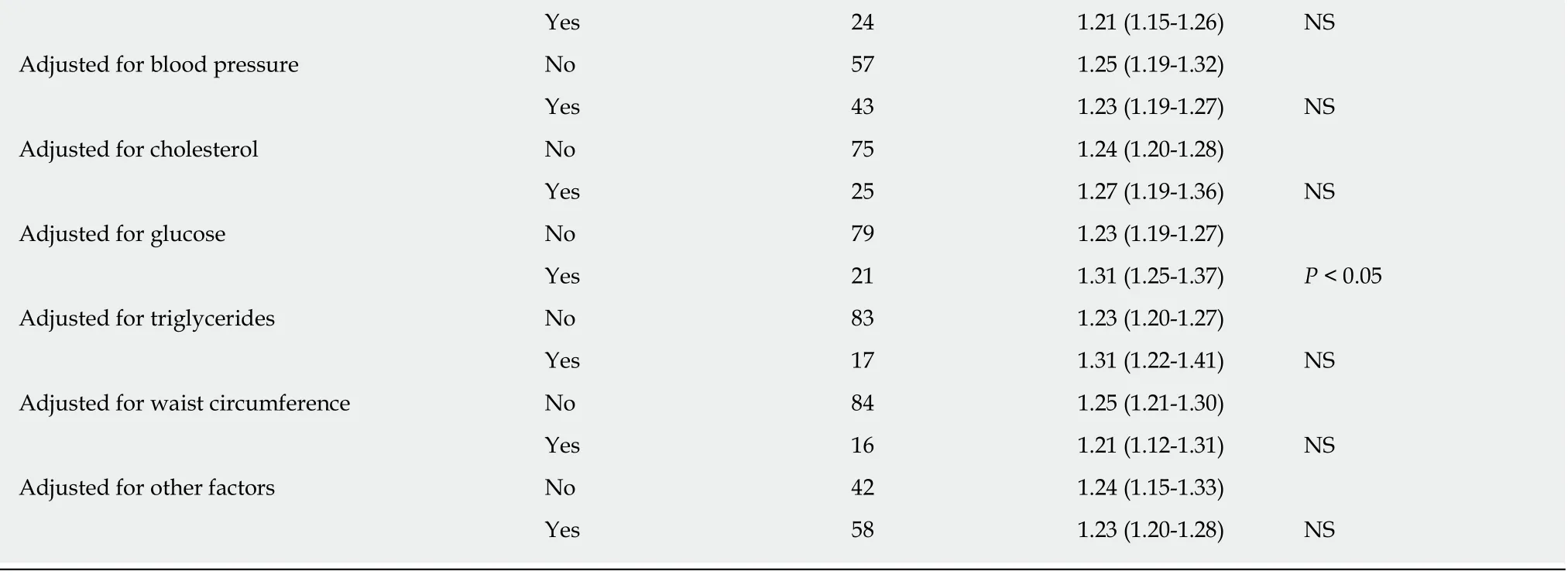

Table 3 presents the overall random-effects estimate, together with a breakdown of the estimates by various factors, with fuller details given in Supplementary file 2.There was evidence (P< 0.05) that the estimates varied by population type with both the estimates from studies restricted to pre-diabetics exceeding 3.There was also evidence that estimates were higher in those that were more adjusted (P< 0.05) or adjusted for various other individual factors (age, alcohol, family history of diabetes,cholesterol, triglycerides - allP< 0.05 - and glucose -P< 0.01), but were lower in those that were adjusted for education (P< 0.05).It is notable, however, that with the exception of two estimates based on less than five RRs, all the RR estimates shown in Table 3 were significantly (P< 0.05) increased.

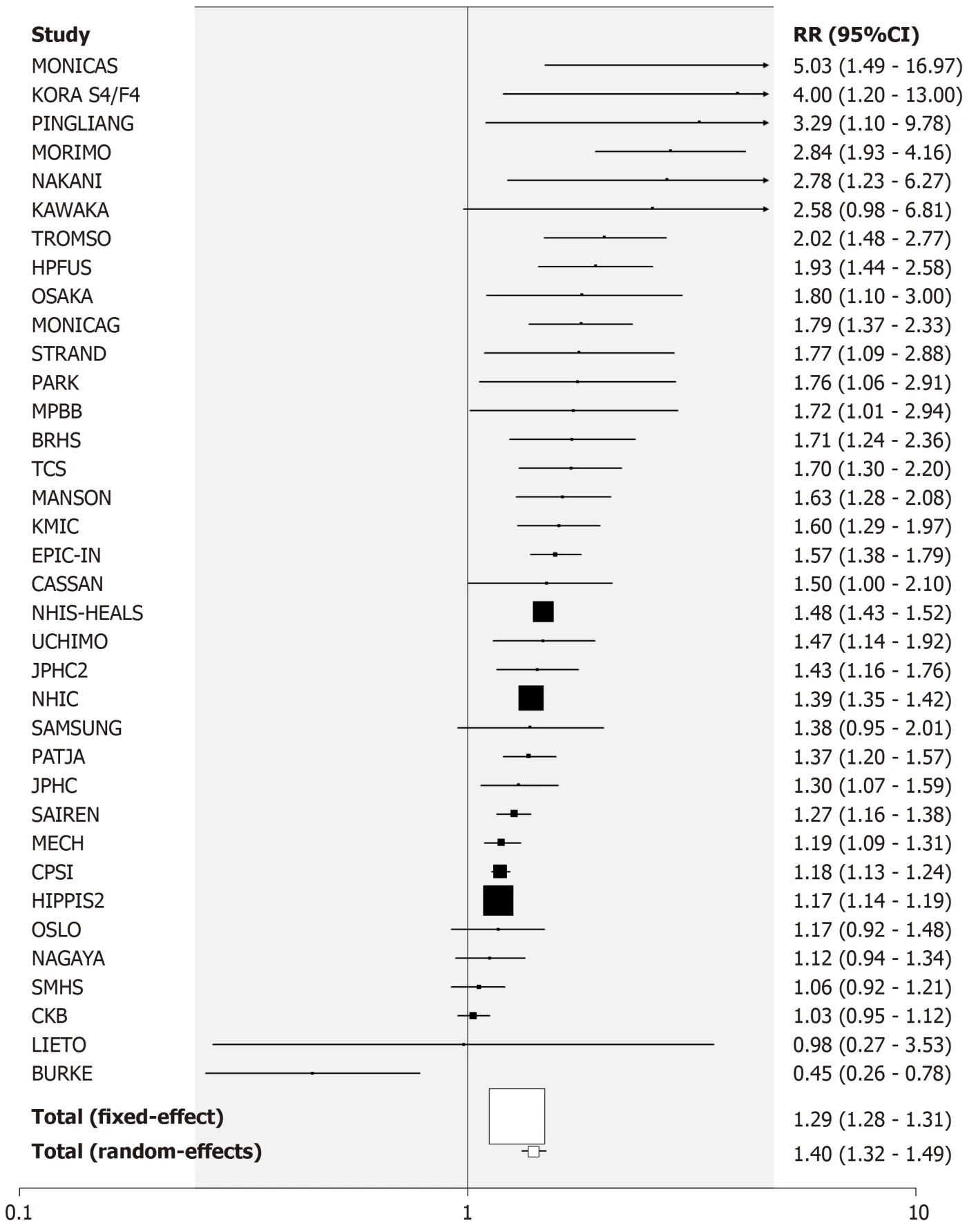

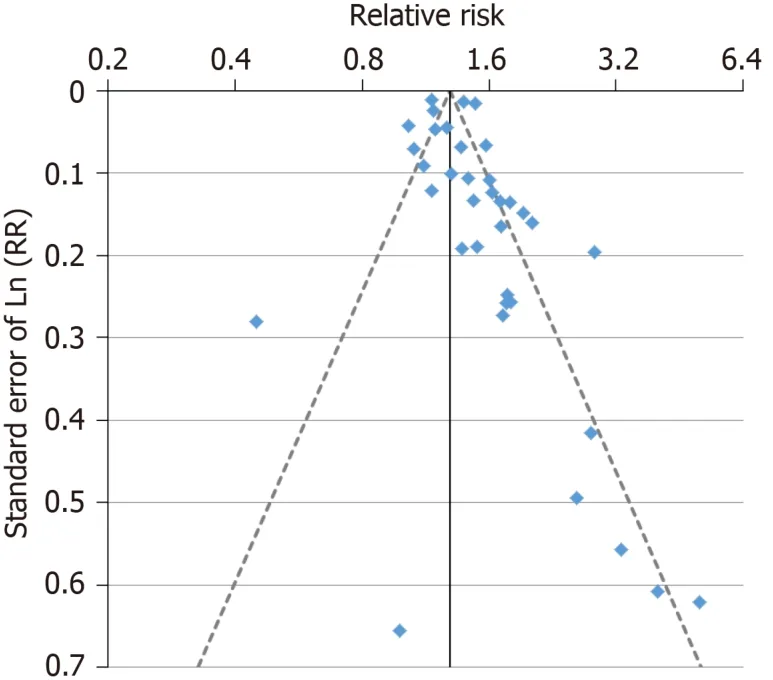

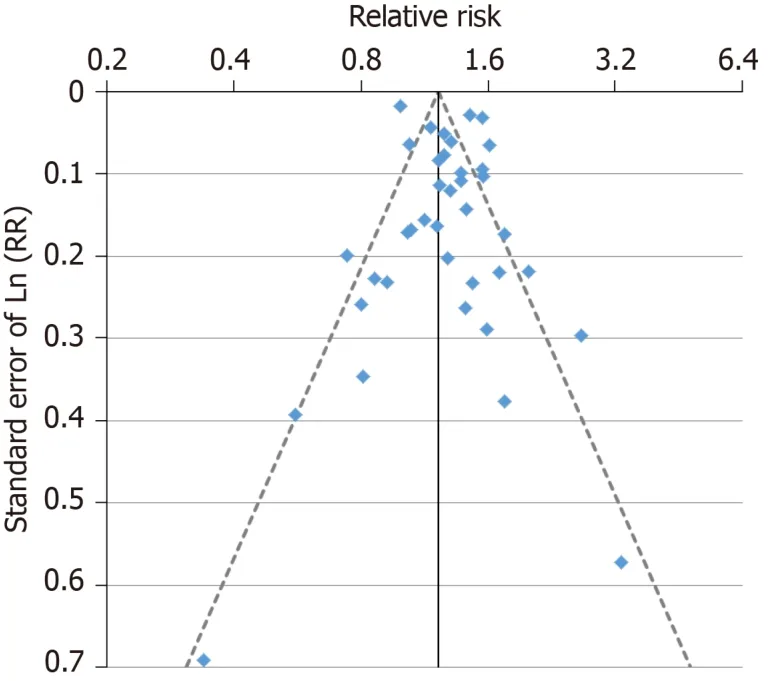

For the analysis subdivided by sex, Figure 1 (females), Figure 2 (males) and Figure 3 (sexes combined) summarize the data in forest plots, while Figure 4 (females),Figure 5 (males) and Figure 6 (sexes combined) present funnel plots to illustrate possible publication bias.No marked publication bias was evident.

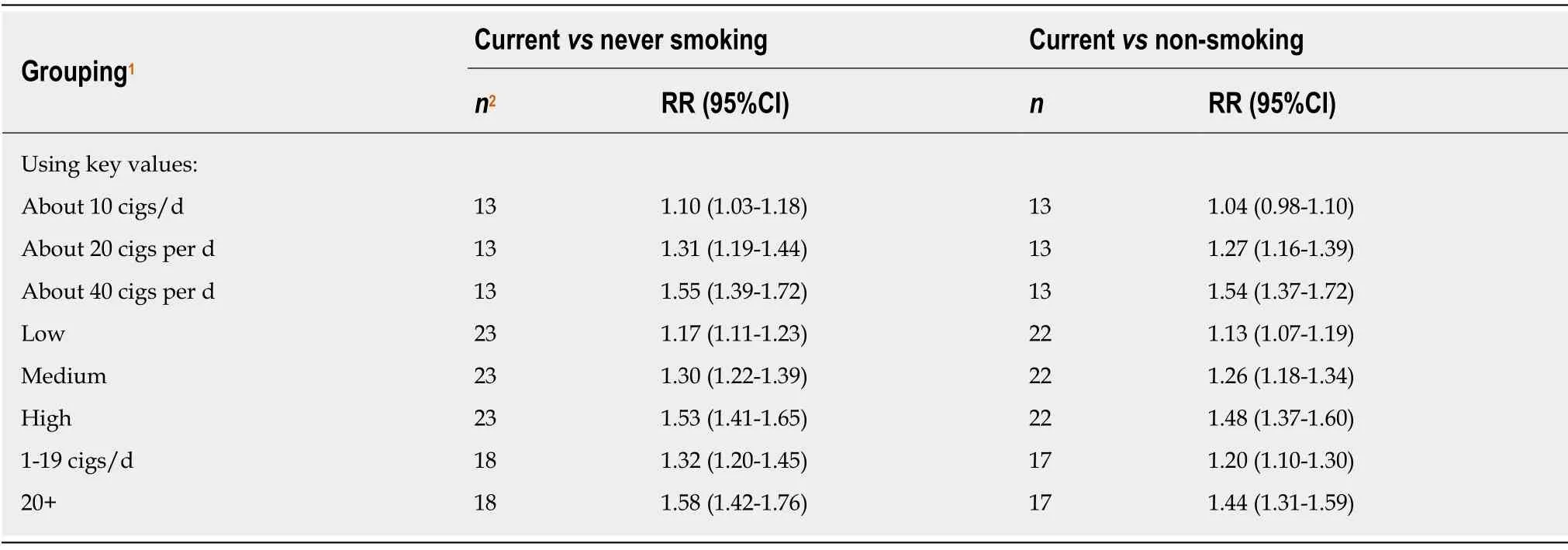

Table 4 (and Supplementary file 3) summarizes the results of the dose-response analysis for currentvsnever smoking.Whichever of the three methods of doseresponse grouping was used, the RR estimates clearly rose with increasing amount smoked, and the increase at each level remained significant (P< 0.05).Note that the sets of estimates are not independent, with all the studies providing results for the key value analysis also contributing to the low/medium/high split.

Current vs non-smoking:There were 156 RR estimates from 133 studies for the comparison of currentvsnon- smoking.Twenty-three studies provided estimates for both sexes, eight for females only, 24 for males only and 78 for sexes combined.

Of the 156 estimates, 27 were below 1, 11 were above 2, with the remaining 118 in the range 1 to 2.The overall fixed-effect RR estimate was 1.20 (95%CI:1.20-1.21), with highly significant heterogeneity (Chisq.1986.7 on 155 df,P< 0.001,I2= 92.2%), and the random-effects estimate was 1.28 (95%CI:1.24-1.32), slightly lower than theestimate for currentvsnever smoking.As for current smoking, there was limited evidence of publication bias (0.01 <P< 0.05).

Table 2 Some characteristics1 of the 145 studies of smoking and type 2 diabetes

[33] North America BOGALUSA United States,Bogalusa General population M+F 1973-2010 9.1 2 7725 176 < 18 BOTNIA [9]/[34] Europe Finland,Botnia Family members of diabetics M+F 1990 7.6 2 2770 138 Any BRHS [35] Europe Britain General population M 1978-1980 16.8 3 7124 290 40-59 BRUNECK[36] Europe Italy,Bruneck General population,White M+F 1990 10.0 2 837 64 40-79 BURKE [37] Oceania Australia Kimberley General population,Aboriginal M+F 1988-1989 12.9 2 493 104 15-88 BWHS [38] North America United States African American subscribers to magazine targeted at black women F 1995 16.0 3 43003 4387 21-69 CASSAN [39] North America United States Majority were veterans,98%Caucasian M 1963 18.0 2 1972 226 20-80 CCHS [40] North America United States,Cleveland General population M+F 2008 5.0 2 5084 872 18+CDCdeC [41] Europe Spain,Canaries M+F 2000-2005 3.5 3 5521 146 18-75 CEHSC [42] Asia Hong Kong(China)General population General population volunteers M+F 1998-2001 9.8 2 53905 806 65+CKB [43] Asia China General population M+F 2004-2008 7.2 2 461211 8784 30-79 CoLaus [44] Europe Switzerland,Lausanne General population M+F 2003-2006 5.5 2 3166 47 35-75 CPSI [45] North America M+F 1959-1960 12.0 3 709827 25397 30+CRISPS [46] Asia Hong Kong(China)United States General Population General population,Chinese M+F 2000-2004 9.0 2 1380 123 Any CURES [47] Asia India,Chennai General population M+F 2001-2003 9.1 2 1376 385 20+DAQING [48] Asia China Care clinic patients with prediabetes,part of diabetes prevention intervention M+F 1986 23.0 3 568 436 Any DEHGHA[49] Europe Netherlands,Ommoord General population M+F 1990-1993 10.8 2 6935 645 55+DE-PLAN[11] Europe Spain,Navarra,Reus and Barcelona Participants in clinical trial on Mediterranean diet,Caucasian M+F 2006 4.2 2 552 124 45-75 DESIR [50] Europe France,Western Volunteers for periodic health checks M+F 1998 9.0 2 3817 203 30-64

DLCS [51] Europe Netherlands,Northern General population,Western Europe M+F 2007-2013 4.0 3 72880 1056 18-90 DNC [52] Europe Denmark Nurses F 1993-1999 15.3 2 24174 1137 44+DONGFE NG[53] Asia China, Da Qing M+F 2008-2010 4.0 3 17690 1390 Any DWECS [54] Europe Denmark Workers M+F 1995-2005 5.0 2 6823 NA 30-59 EPIC-IN [55] Europe 8 countries7 Subset of Retired employees M+F 1991 11.7 3 23501 10327 Any participants in EPICInterAct cohort ESTHER [56] Europe Germany,Saarland M+F 2000-2002 8.0 3 7462 718 50-75 FAGERB [57] Europe Sweden,G?teborg General population General population,Caucasian F 2001-2004 5.5 2 341 69 64 FINNMA RK[58] Europe Norway,Finnmark General population M+F 1997-1978 12.0 2 11654 162 35-52 GLOSTR UP[59] Europe Denmark,Glostrup General population M 1982-2001 18.9 2 5350 211 30-70 GNHIES [60] Europe Germany General population(non institutiona lized)M+F 1997-1999 5.0 2 3625 82 18-79 HDNNC DS[12] Asia China,Harbin General population,Chinese M+F 2010 4.2 3 7133 578 20-74 M+F 2000-2001 7.0 2 4110 81 40-79 HEINZN [61]/[62] Europe Germany,Western HEALTH 2000[10] Europe Finland General population M+F 2000-2003 5.1 3 3547 319 45-75 HENAN [63] Asia China,Henan General population General population,N Chinese ancestry M+F 2007-2008 6.0 3 12272 775 18+HIPOPOHP[64] Asia Japan Employees M+F 1999 3.4 3 6498 229 Any HIPPIS1 [65] Europe England and Wales Primary care patients M+F 1993-2008 8.0 2 2540753 78081 25-79 HIPPIS2 [66] Europe England Primary care patients M+F 2005-2016 3.9 2 8186705 178314 25-84 M+F 1988 11.8 2 1935 286 40-79 HPFUS [68] North America HISAYA MA[67] Asia Japan,Hisayama General population United States Health professionals M 1986 6.0 3 41810 509 40-75 HPHS [12] Asia China,Harbin General population,Chinese M+F 2008 4.2 3 3350 244 20-74 HUNT [69] Europe Norway,Nord-Tr?ndelag General population M+F 1984-1997 11.0 3 90819 1860 20+ICARIA [70] Europe Spain Spanish workers M+F 2004-2007 4.1 3 380366 9960 18-65 ICS [71] Asia Iran,Isfahan,Arak and Najafabad General population M+F 2001 7.0 2 2980 389 35+

IPC [72] Europe France,Paris Workers and those seeking employment who had undergone 2 health checks M+F 1998-2010 5.3 2 22567 527 18+IRAS [73] North America United States, 4 areas8 General population M+F 1992-1993 5.0 2 906 148 40-69 IWHS [74] North America United States,Iowa Communit y based F 1986 13.2 1 36839 3281 55-69 JACC [75] Asia Japan Communit y based M+F 1988-1990 5.0 1 16160 396 40-79 J-ECOH [76]/[77] Asia Japan Employees M+F 2008-2010 3.9 2 53930 2441 15-83 JHS [78] North America United States,Mississippi General population,Black M+F 2000-2004 8.0 2 2991 479 21-84 JPHC [79] Asia Japan General population M+F 1990 10.0 1 28893 1183 40-59 JPHC2 [80] Asia Japan General population M+F 1995-1998 5.0 1 59834 1100 45-74 KANGBUK[81] Asia South Korea,Seoul Individuals undergoing health screening M+F 2002 5.6 3 174314 5544 18+KAWAHA[82] Asia Japan,Kitakyushu City City workers M+F 2008 3.7 2 52781 4369 20-89 KAWAKA[83] Asia Japan,electrical company Employees of large electrical company M 1984 8.0 2 2312 41 18-53 KMIC [84] Asia South Korea Government and school employees M 1990-1986 8.0 2 27635 1170 35-44 KoGES-K [85]/[86] Asia South Korea,Kangwha Community based M+F 2006-2011 4.0 2 2079 142 40+KORA F4/FF4[87] Europe Germany,Augsburg General population M+F 2006-2008 7.0 2 504 76 62-81 M+F 1999-2001 7.0 2 887 93 55-74 KPNW [89] North America KORA S4/F4[88] Europe Germany,Augsburg General population United States,Portland Health care members M+F 1997-2000 6.8 2 46578 1854 40+LEICESTER[90] Europe England,Leicester With clinical diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome F 1988-2009 5.2 2 2164 138 16-79 LIETO [91] Europe Finland,Leito General population M 1998-1999 9.0 2 430 30 64+LINDBE [92] Europe Denmark,Copenhagen General population M+F 2001-2003 8.5 2 5349 136 20-94 LLP [93] Europe England,Liverpool M+F 1998-2008 10.0 2 8753 763 45-79 MAILES [94] Oceania Australia,Adelaide General population General population M 2002-2006 4.9 3 1597 232 35-80 MANSON[95] North America United States Physi-cians in randomized trial M 1982 12.0 1 21068 770 40-84

MECC [96] North America United States,Hawaii and California General population,African American and Latino M+F 1993-1996 14.0 3 48995 15833 50-75 MECH [97] North America United States,Hawaii General population,Caucasian,Hawaiian,Japanese,American M+F 1993-1996 12.1 3 74970 8559 45-75 MESA [98]/[99] North America United States, 6 states9 General population,White,Black,Hispanic or Chinese M+F 2000-2002 10.2 2 5931 359 45-84 MFH [10] Europe Finland General population M+F 1978-1980 10.0 2 4517 145 40-79 MJH [100] Asia Taiwan(China)Paid members of private health screening program,Chinese M+F 2001-2014 6.7 3 147908 4781 18+MONICAG[101] Europe Germany,Augsburg General population M+F 1984-1995 12.5 3 10892 672 25-74 MONICAS[102] Europe Sweden,Northern General population M 1986-1994 8.7 3 1275 27 25-74 MORIMO [103]/[104] Asia Japan,Nagano prefecture Volunteers in Nagano Prefecture M+F 1990-1992 10.1 3 5872 595 40-69 MOZAFF [105] North America United States, 4 states10 Ambulatory,noninstitutionalized subjects M+F 1989-1992 10.0 2 4883 337 65+MPBB [106] North America United States,Michigan Subjects who had injected food contaminated with polybrominated biphenyls,99.8%White M+F 1976 25.0 3 1384 180 20+MPP [9] Europe Sweden,Malmo M+F 1974-1992 24.8 2 16061 2063 Any MUTUAL[107] Asia Japan Civil servants General population M+F 2000 6.5 2 5848 287 30-59 MYHUS [108] Asia Japan Employees M+F 2004 5.0 3 13700 408 36-55 NAGALA [109]/[110] Asia Japan, Gifu Subjects M+F 2004-2015 5.1 3 17810 804 Any receiving medical check-ups NAGAYA[111] Asia Japan,Nagoya Volunteer attendants of annual health check ups M 1988-1990 7.4 3 16829 869 30-59 NAKANI[112] Asia Japan,Osaka Employees M 1994 5.0 2 1266 54 35-59 NCDS [113] Europe Britain Birth M+F 1974 17.0 1 4945 28 16 cohort from March 1958 NHANES[114] North America United States General population M+F 1971-1975 18.0 3 4830 443 25-74

NHIC [115] Asia South Korea Recipients of biennial medical check-ups M+F 1992-1995 14.0 2 1236443 89422 30-95 NHISHEALS[116] Asia South Korea Recipients of national health screen test M+F 2002-2003 10.8 2 359349 37678 40-79 NHISNCS[117] Asia South Korea Nationally representative M+F 2002 6.8 2 51405 2749 20+NHS [118] North America 1976-1982 24.0 3 100526 5392 30-55 NHSII [13] North America United States Registered Nurses F United States Registered Nurses F 1989-1991 23.0 3 88086 5441 25-42 NIH -AARP[119] North America United States, 6 states11 General population M+F 1995-1996 11.0 1 207479 18000 50-71 NOMAS [120] North America United States,North Manhattan General population,White,Black or Hispanic M+F 1993-2001 11.0 3 2430 449 40+NOVAK [121] Europe Sweden,Gothenburg General population(intervention group in ineffective trial)M 1970-1973 35.0 2 6828 899 47-56 OLMSTED[122] North America United States,Rochester General population who also took at least one medication M+F 1999-2004 6.0 2 13508 1182 18+ONAT [123] Asia Turkey Participants in nationwide survey M+F 1997-1998 5.9 3 3385 216 28+OSAKA [124] Asia Japan,Osaka General population undergoing basic health check-ups M+F 2001 4.0 2 9327 171 40-74 OSLO [125] Europe Norway,Oslo 1972-1973 28.0 3 6382 584 40-49 OSTENS [126] Europe Sweden,Stockholm General population M General population M 1992-1994 10.0 2 2383 99 35-56 PARK [127] Asia South Korea, not known Undergoing health examinations M 2002 4.0 2 1717 50 Any PATJA [128] Europe Finland,North Karelia and Kuopio General population M+F 1972-1992 21.0 2 41372 2770 25-64 PINGLIA NG[129] Asia China, Ping Liang General population prediabetic at baseline M+F 2002-2003 10.8 2 334 98 Any PMMJS [130] Asia China,Jiangsu General population M+F 2000-2004 5.0 2 3598 160 35-74

[11] Europe Spain,Navarra,Reus and Barcelona PREDIMED Participants in clinical trial on Mediterranean diet,Caucasian M+F 2003-2009 4.8 2 1381 155 55-80 PREDIMERC[131] Europe Spain,Madrid General population M+F 2007 6.4 2 2048 44 30-74 PREVEND[132] Europe Netherlands,Groningen General population M+F 1997-1998 11.4 3 7953 447 Any REGARDS[133] North America United States General population,Black or White M+F 2003-2007 9.5 2 7758 891 45+SABE [134] South America M+F 2000 6.0 1 914 72 60+SAIREN [135] Asia Japan,Ibaraki-ken Brazil, Sào Paulo General population General population undergoing annual health check-ups M+F 1993 5.0 2 128141 7990 40-79 SALSA [136] North America United States,Sacramento General population,Latino M+F 1998-1999 10.0 3 782 144 60+SAMSUNG[137] Asia South Korea,Seoul Undergoing health examinations,Korean M 2006 6.0 3 1774 180 20+M+F 2002 8.3 3 2631 110 18+SAWADA[139] Asia Japan,Tokyo SAPALDIA[138] Europe Switzerland General population Employees of Tokyo Gas Company M 1985 14.0 3 4745 280 20-41 SAX45 [140] Oceania Australia,New South Wales General population M+F 2006-2008 3.4 1 54997 888 45+SCCS [14] North America United States,Southern General population,Black or White M+F 2002-2009 4.5 1 35892 3439 40-79 SCCS2 [14] North America United States,Southern General population,Black or White M+F 201212 3.0 1 20712 1708 43-82 SHFS [141] North America United States, 4 states13 Members of multiplex families,American Indians M+F 2001-2003 5.5 2 431 133 14+SHIP [142] Europe Germany,Augsburg Caucasian German citizens M+F 1997-2001 11.1 2 2034 206 20-81 SMHS [143] Asia China,Shanghai General population M 2002-2006 5.4 3 51464 1304 40-74 STILLW [144] Europe Finland Employees of Finnish Company M 1986 17.0 2 5827 313 18-65 STRAND [145] Europe Finland,Helsinki Volunteer executives and businessmen M 1974-1975 20.0 3 1802 94 40-56

1Where relevant, characteristics are shown for the main reference, given first in the column Main/Other Ref.2If location not stated, then national.3All races are included unless stated otherwise.4NA means not available.Some studies provided results for more than one follow-up time.Here the longest follow-up is indicated.The follow-up times are presented as means, medians or averages to various numbers of decimal places.The values shown are the best estimate available.51 = self-report only; 2 = medical records only; 3 = both.6Studies HPFUS, NHS and NHSII.7France, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and Denmark.8Los Angeles, Oakland, San Antonio and San Juis Valley.9Maryland, Illinois, North Carolina, California, New York and Minnesota.10North Carolina, California, Maryland and Pennsylvania.11California, Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey, North Carolina and Pennsylvania.12Subset of SCCS who were diabetes free at end of SCCS follow-up.Unclear what the baseline date range of SCCS2 actually was.13Arizona, North and South Dakota and Oklahoma.M:Male; F:Female.

Table 3 also presents the overall random-effects estimate for currentvsnonsmoking, as well as a breakdown of the estimates by different factors (see also Supplementary file 4).As for currentvsnever smoking, the random-effects estimate was elevated in all subdivisions of the data, significantly so except where based on very few estimates.There was little evidence of variation in the RR in subdivisions of the data by level of the various factors studied, the most notable exceptions being the somewhat higher estimate in studies adjusted rather than unadjusted for family history of diabetes, and the variation by continent.

Table 4 (and Supplementary file 5) summarizes the results of the dose-response analysis for currentvsnon-smoking.As for currentvsnever smoking, there was clear evidence that risk rises with amount smoked, whichever dose-response grouping is used.

Forest and funnel plots for the analysis subdivided by sex are shown in Supplementary file 6.

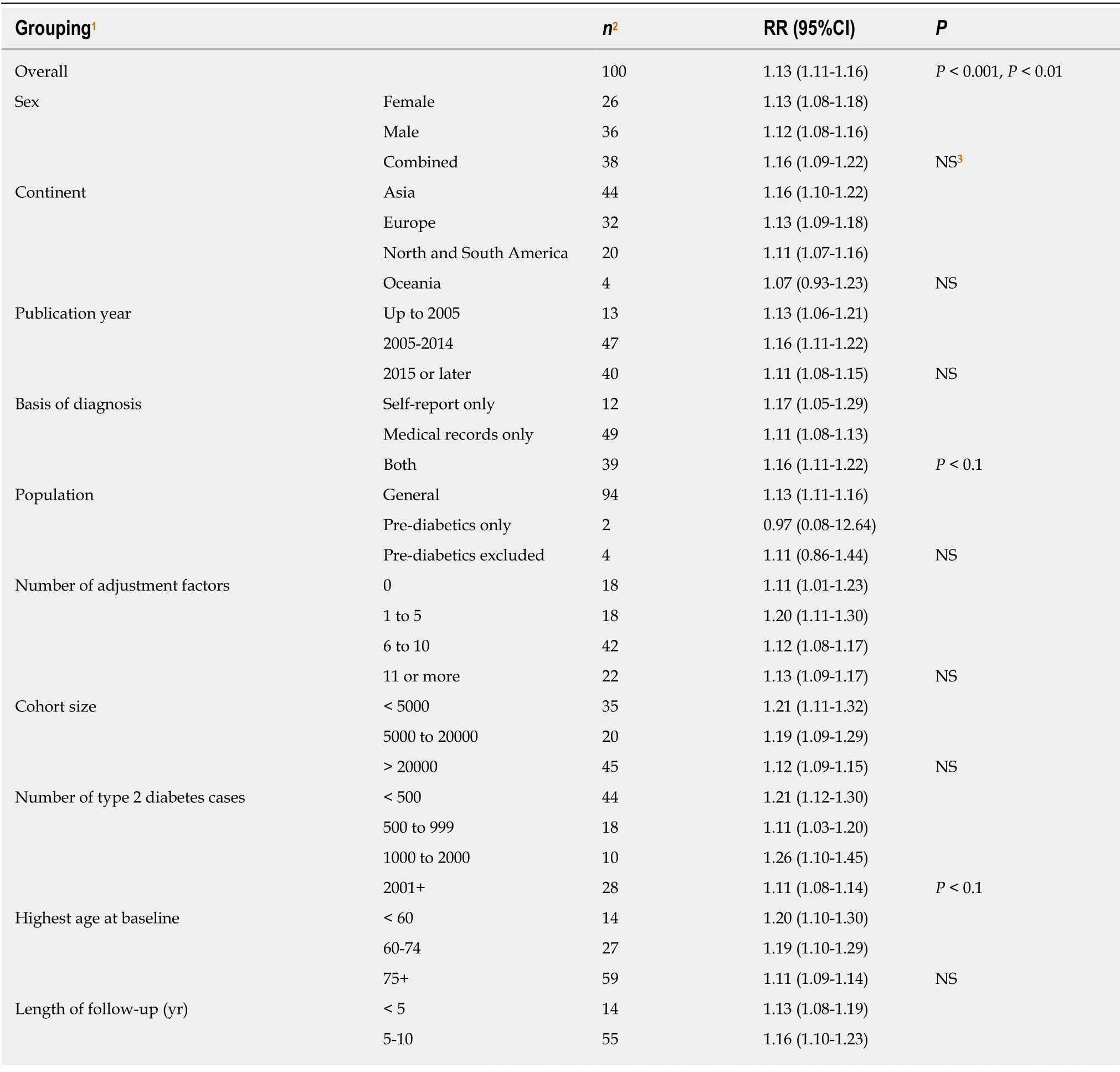

Former vs never smoking:There were 100 RR estimates from 81 studies for the comparison of formervsnever smoking.Nineteen provided estimates for both sexes,seven for females only, 17 for males only and 38 for sexes combined.

Of the 100 estimates, 18 were below 1, 7 were above 2, with the remaining 75 in the range 1 to 2.The overall fixed-effect estimate was 1.09 (95%CI:1.08-1.10), with highly significant heterogeneity (Chisq.263.6 on 99 df,P< 0.001,I2= 62.4%).The randomeffects estimate was 1.13 (95%CI:1.11-1.16).Somewhat stronger evidence of publication bias (0.001 <P< 0.01) was seen than for current smoking.

Table 5 presents the overall random effects estimate, together with a breakdown of the estimates by different factors (see also Supplementary file 7).There was no strong evidence (P< 0.01) of variation in the RR by level of any factor, with estimates slightly elevated in all subgroupings except where based on very few estimates.

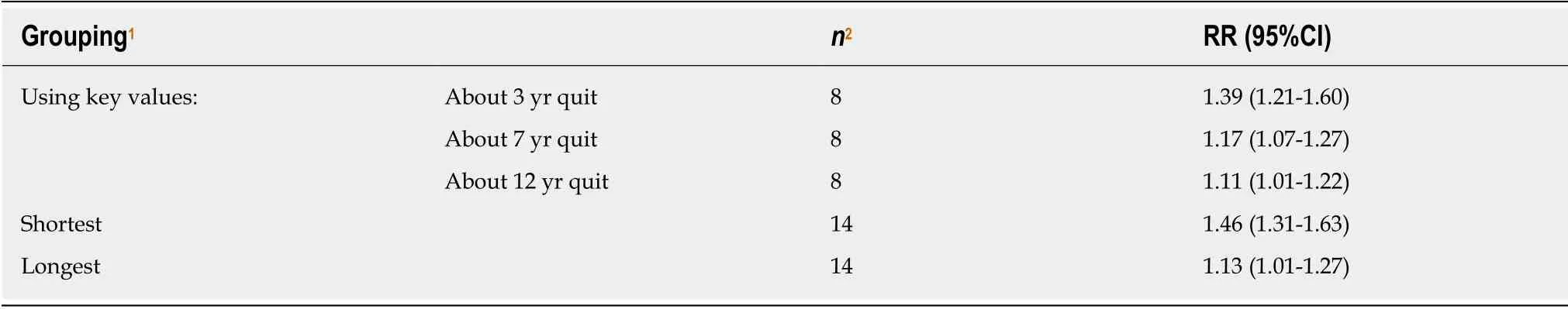

Table 6 (and Supplementary file 8) summarizes the results of the dose-response analysis for formervsnever smoking.These showed clear evidence that the RR declined with increasing time since quitting.

Again, forest and funnel plots are shown in Supplementary file 6.

Ever vs never smoking:One hundred RRs were available from 82 studies.The overall fixed-effect RR estimate was 1.17 (95%CI:1.16-1.18) with evidence of considerable heterogeneity (Chisq.897.37 on 99 df,P< 0.001,I2= 89.0%), the random-effect estimate being 1.25 (95%CI:1.21-1.28).There was some evidence of publication bias(0.001 <P< 0.01).RRs were generally elevated in all subgroups, the strongest evidence of variation by any factor (P< 0.001) relating to adjustment for education,unadjusted estimates (RR = 1.29, 95%CI:1.24-1.34) being higher than adjusted ones(RR = 1.17, 95%CI:1.12-1.21).There was also weaker evidence (P< 0.05) that RRs were somewhat higher in Asia, and somewhat lower in populations with a baseline upper age limit of 75 or more, or if the RRs were unadjusted for glucose.See Table 8 and Supplementary File 9 for fuller details.

Only one of the studies provided information on risk by amount smoked, so no dose-response meta-analyses were possible.

Again, forest and funnel plots are shown in Supplementary file 6.

Ratio of RRs for highest to lowest BMI groupings:Six studies provided results by level of BMI, three of these giving results for each sex separately.One study provided data only for currentvsnever and formervsnever smoking, while the others also provided data for currentvsnon-smoking and evervsnever smoking.None of the meta-analyses provided any evidence of variation in RR by level of BMI, the random effects meta-analysis estimate of the highest to lowest ratio being 1.20 (95%CI:0.92-1.57) for currentvsnever smoking, 1.06 (95%CI:0.82-1.36) for currentvsnon-smoking,1.12 (0.95-1.32) for formervsnever smoking, and 1.03 (95%CI:0.87-1.23) for evervsnever smoking, based on, respectively, 9, 7, 9 and 7 estimates.(See Supplemen-tary file 10).

Supplementary files

Supplementary file 1 gives further details of the literature search, including a list of the 42 publications rejected during data entry, giving the reasons for rejection, and a description of how multiple publications from a study were dealt with.

Supplementary Files 2, 4, 7 and 9 give full details of the results for the mainanalysis of, respectively, currentvsnever smoking, currentvsnon-smoking, formervsnever smoking and evervsnever smoking.Each file is laid out similarly.Introductory pages describe the content and layout of the output, and explain the abbreviations used and the decisions made where multiple results were available for a single study.Table 1 of each Supplementary File then gives details of each candidate RR selected from the main and subsidiary publications for each study, while Table 2 of each file gives details of the RRs actually used in the analyses, and Tables 3-27 of each file give full results of the meta-analyses subdivided by each of the 25 factors considered (sex,continent,etc.).

Table 3 Meta-analysis random effect relative risks for current smoking

75+ 59 1.29 (1.24-1.35)P < 0.1 96 1.26 (1.21-1.31)NS Length of follow-up (yr) < 5 14 1.27 (1.19-1.35)25 1.24 (1.15-1.34)5-10 55 1.38 (1.30-1.47)81 1.34 (1.28-1.40)> 10 30 1.31 (1.22-1.39)NS 50 1.22 (1.17-1.28)P < 0.05 Definition of smoking Cigarette 47 1.32 (1.27-1.38)63 1.25 (1.21-1.29)Smoking 50 1.36 (1.26-1.46)89 1.30 (1.23-1.37)Tobacco 2 1.10 (0.94-1.29)P < 0.1 4 1.16 (1.06-1.27)P < 0.1 Adjusted for age No 20 1.17 (1.04-1.32)41 1.22 (1.12-1.33)Yes 79 1.35 (1.31-1.41)P < 0.05 115 1.29 (1.25-1.33)NS Adjusted for sex No 72 1.35 (1.29-1.41)107 1.27 (1.23-1.32)Yes 27 1.29 (1.20-1.39)NS 49 1.29 (1.20-1.38)NS Adjusted for BMI No 29 1.24 (1.11-1.38)55 1.22 (1.13-1.32)Yes 70 1.35 (1.30-1.41)NS 101 1.30 (1.26-1.34)NS Adjusted for physical activity No 41 1.27 (1.20-1.35)87 1.27 (1.21-1.33)Yes 58 1.36 (1.30-1.43)P < 0.1 69 1.28 (1.23-1.33)NS Adjusted for alcohol consumption 87 1.26 (1.20-1.32)Yes 57 1.37 (1.31-1.43)No 42 1.26 (1.19-1.34)P < 0.05 69 1.29 (1.25-1.33)NS Adjusted for family history of diabetes 99 1.23 (1.17-1.29)Yes 38 1.41 (1.33-1.49)No 61 1.28 (1.22-1.35)P < 0.05 57 1.34 (1.29-1.40)P < 0.01 Adjusted for education No 63 1.37 (1.31-1.44)115 1.29 (1.24-1.35)Yes 36 1.28 (1.21-1.34)P < 0.05 41 1.23 (1.18-1.28)P < 0.1 Adjusted for diet No 74 1.35 (1.29-1.41)126 1.29 (1.24-1.34)Yes 25 1.30 (1.22-1.38)NS 30 1.23 (1.18-1.28)P < 0.1 Adjusted for blood pressure No 53 1.31 (1.24-1.40)88 1.27 (1.21-1.34)Yes 46 1.35 (1.29-1.41)NS 68 1.28 (1.24-1.33)NS Adjusted for cholesterol No 72 1.30 (1.25-1.35)115 1.26 (1.22-1.31)Yes 27 1.40 (1.32-1.48)P < 0.05 41 1.32 (1.25-1.39)NS Adjusted for glucose No 79 1.30 (1.25-1.35)116 1.26 (1.22-1.31)Yes 20 1.44 (1.35-1.54)P < 0.01 40 1.34 (1.27-1.41)NS Adjusted for triglycerides No 80 1.30 (1.25-1.36)124 1.27 (1.22-1.31)Yes 19 1.45 (1.33-1.58)P < 0.05 32 1.34 (1.24-1.44)NS Adjusted for waist circumference No 82 1.34 (1.29-1.40)136 1.28 (1.24-1.32)Yes 17 1.29 (1.19-1.41)NS 20 1.25 (1.16-1.35)NS

1For sex, publication year, basis of diagnosis, number of adjustment factors, definition of smoking and age adjusted the grouping relates to characteristics of the relative risk.For other factors it relates to characteristics of the study.2Number of estimates combined.3NS means not significant, P ≥ 0.1.For the overall analysis, the first P value relates to heterogeneity between estimates and the second to publication bias.For the other analyses it relates to a test of heterogeneity between the random-effects estimates at each level.Information on publication bias by level of each factor studied is given in Supplementary Files 2 and 4.NS:Not significant; CI:Confidence interval; RR:Relative risk.

Supplementary Files 3, 5 and 8 give full details of the dose-response analysis of respectively, currentvsnever smoking (by amount smoked), currentvsnon- smoking(by amount smoked) and formervsnever smoking (by year quit).Each file includes separate blocks of description and results, similar to those for Supple-mentary Files 2, 4 7 and 9 , but only including Tables 1-3 of those files, with Table 3 only showing results subdivided by sex.Each block relates to a specific doseresponse level (e.g., about 10 for amount smoked).

Supplementary file 6 presents forest and funnel plots for currentvsnon-smoking,formervsnever smoking and evervsnever smoking, similar to those shown in Figures 1-6 of the paper for currentvsnever smoking.

Supplementary file 10 gives the results of meta-analyses of ratios of relative risks for the highest to lowest BMI groupings available.

DISCUSSION

According to the United States National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Health Information Center[162], risk factors for type 2 diabetes include overweight/obesity, age, a family history of diabetes, high blood pressure, low highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol, high triglycerides, a history of gestational diabetes,giving birth to a baby weighing 9 pounds or more, physical inactivity, a history of heart disease or stroke, as well as being in certain ethnic groups or having certain diseases.Smoking is not mentioned as a risk factor.

The meta-analyses we conducted indicate a modest relationship of smoking to risk of type 2 diabetes.This can be seen for current smoking (whether compared with never or non-smokers), former smoking and ever smoking.While there was clear evidence of heterogeneity in the RRs, the random-effects RRs showed increased risks in males and females, in younger and older subjects, in all continents studied,regardless of the basis of diagnosis, and regardless of the definition of smoking used.Despite the evidence of heterogeneity between the individual estimates, a striking feature of the results presented in Tables 3 and 5 was the fact that the estimates were elevated in virtually every subdivision of the data, whichever factor the subdivision was based on.There was also clear evidence (see Tables 4 and 6) of an increasing risk with increasing amount smoked by current smokers and of decreasing risk with increasing time quit by former smokers.Though there was some evidence of variation in risk by level of some factors, this did not suggest that the elevation in risk was unique to some populations or could be explained by adjustment for specific confounding variables.Nor did the fact that some studies did not report an elevation affect the overall conclusion.With a relatively weak association (with RRs about 1.3 for current smoking and about 1.13 for former smoking) it might be expected that some smaller studies would not detect an elevated risk.However, this did not affect the overall conclusion.Indeed, it was notable that, of the 12 RR estimates for currentvsnever smoking that were below 1.0, only one was statistically significant (atP<0.05), whereas, of the 87 estimates above 1.0, as many as 63 were.

Figure 1 Forest plot for current vs never smoking, results for females.

Given the weight of evidence from this review and others, smoking may be a contributory factor to type 2 diabetes.Publication bias, for which some evidence was detected, might have led to some over-estimation of the association, due to some studies finding no relationship not presenting their results.Bias due to misclassification of smoking status would only tend to bias the observed relationship down, not produce an association that did not truly exist.Failure to control properly for diet, BMI or related factors would not seem to be an explanation of the association as elevated risks were seen in studies that adjusted for these factors.That said, it is clear from Table 3 that many of the studies did not adjust for various factors listed in the first paragraph of the discussion, so that the association seen between smoking and type 2 diabetes may have suffered from uncontrolled confounding to some extent.

This review has limitations, some unavoidable.Lack of access to individual person data limited the detail of the meta-analyses that can be carried out, but obtaining such data was not practical.Obtaining a reliable definition of outcome, exposure and adjustment variables was sometimes hindered by incomplete information in the source papers.Some studies involved relatively few type 2 diabetes cases, but associations were evident both in studies with small and large numbers.It is possible that our analyses did not make full use of all the data collected, but this is inevitable in a paper of reasonable length.We would be willing to make our database available to bona fide researchers for further analysis.

Our results are consistent with those of the earlier review by Panet al[1]based on 88 prospective studies.Although our analyses were based on a considerably larger number of studies, 145, our estimated random-effect RRs of 1.33, 1.28 and 1.13 for currentvsnever, currentvsnon, and formervsnever smoking were similar to their corresponding estimates of 1.40, 1.35 and 1.14.Like us, they also found dose-response relationships with amount smoked and years since quitting.The interested reader is referred to that paper for further discussion of limitations of the data and interpretation of the results.

Figure 2 Forest plot for current vs never smoking, results for males.

That paper refers to “the high prevalence of smoking in many countries and the increasing number of diabetes worldwide” and considers that “reducing tobacco use should be prioritized as a key public health strategy to prevent and control global epidemic of diabetes”.Though reduction of smoking is clearly important to limit a range of diseases such as lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease, one must question this prioritization, in the light of the range of other risk factors for type 2 diabetes noted above, and the evidence that diabetes incidence is rising fast worldwide[56], while smoking is declining[2].As a strategy,controlling diet may be much more beneficial.The work of Tayloret al[163]suggests that, in many people, type 2 diabetes can be completely reversed quite rapidly by appropriate diet and weight loss.

In conclusion, the analyses confirm earlier reports of a modest dose-related association of current smoking and a weaker dose-related association of former smoking with risk of type 2 diabetes.

Table 4 Dose-response analyses for current smoking

Table 5 Meta-analysis random effects relative risks for former (vs never) smoking

1For sex, publication year, basis of diagnosis, number of adjustment factors, definition of smoking and age adjusted the grouping relates to characteristics of the RR.For other factors it relates to characteristics of the study.2Number of estimates combined.3NS means not significant, P ≥ 0.1.For the overall analysis, the first P value relates to heterogeneity between estimates and the second to publication bias.For the other analyses it relates to a test of heterogeneity between the random-effects estimates at each level.Information on publication bias by level of each factor studied is given in Supplementary file 6.CI:Confidence interval; RR:Relative risk; NS:Not significant; BMI:Body mass index.

Table 6 Dose-response analyses for former vs never smoking (years quit)

Table 7 Meta-analysis random effects relative risks for ever (vs never) smoking

1For sex, publication year, basis of diagnosis, number of adjustment factors, definition of smoking and age adjusted the grouping relates to characteristics of the relative risk.For other factors it relates to characteristics of the study.2Number of estimates combined.3NS means not significant, P ≥ 0.1.For the overall analysis, the first P value relates to heterogeneity between estimates and the second to publication bias.For the other analyses it relates to a test of heterogeneity between the random-effects estimates at each level.Information on publication bias by level of each factor studied is given in Supplementary file 8.CI:Confidence interval; RR:Relative risk; NS:Not significant.

Figure 3 Forest plot for current vs never smoking, results for sexes combined.

Figure 4 Funnel plot for current vs never smoking, results for females.

Figure 5 Funnel plot for current vs never smoking, results for males.

Figure 6 Funnel plot for current vs never smoking, results for sexes combined.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

A systematic review of the relationship between smoking and incident type 2 diabetes, based on 88 epidemiological prospective studies, was published in 2015.Much new evidence on this relationship has become available since then.

Research motivation

To obtain up-to-date evidence relating smoking to type 2 diabetes.

Research objecti ves

To systematically review available evidence from prospective studies on the relationship of type 2 diabetes onset to ever, current or former smoking of cigarettes or of any tobacco product,including dose-response data.

Research methods

Attention was restricted to prospective studies of populations free of type 2 diabetes at baseline which related subsequent incidence of the disease to one or more defined major or dose-related smoking indices.The major indices compared ever, current or former smokers to never smokers and current smokers to non-current smokers.The dose-related indices concerned amount currently smoked and years quit.Literature searches identified relevant papers from previous reviews, from Medline searches and from references lists of relevant papers identified.Data were extracted on study details and on the relative risks required, estimated if required using standard methods.Care was taken to avoid overlap of data from the same study from multiple publications.Fixed-effect and random-effects meta-analyses were conducted, including tests of heterogeneity and publication bias.Where a study provided multiple estimates, a preference scheme was used involving factors such as level of adjustment for confounding factors, length of follow-up and age range considered.Sex-specific results were used, if available.Effect estimates were derived based on all the selected RRs, and also for those subdivided by various categorical variables - sex, continent, year of publication, basis of diagnosis of diabetes, initial diabetes status of the population, age, length of follow-up, definition of smoking, and whether a range of different variables were adjusted for.

Research results

The literature searches identified 157 relevant publications providing results from 145 studies.Overall random-effect RR estimates were 1.33 [95% confidence interval (CI):1.28-1.38] for current vs never smoking, 128 (95%CI:1.24-1.32) for current vs non-smoking, 1.13 (95%CI:1.11-1.16) for former vs never smoking and 1.25 (95%CI:1.21-1.28) for ever vs never smoking, each combined estimate being based on at least 99 individual estimates.Estimates were generally elevated in each subdivision of the data by the categorical variables considered, though in some cases RR estimates varied significantly (P < 0.05) by level.The dose-response analysis showed that risk increased with increasing amount smoked, and reduced with increasing time quit.

Research conclusions

Our analyses confirmed and extended reports of a modest dose-related association of current smoking and a weaker dose-related association of former smoking with risk of type 2 diabetes.The evidence suggests smoking may contribute to the risk of type 2 diabetes, though our estimates may be affected by publication bias and some uncontrolled confounding.Although reduction of smoking is clearly important to limit risk of diseases such as lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease, the worldwide rise in incidence of type 2 diabetes, coupled with a decline in smoking, suggests that control of other factors, such as diet, may be much more beneficial in reducing type 2 diabetes risk.

Research perspectives

Our analyses suggest strongly that there is a modest increased risk of type 2 diabetes associated with current smoking which is greater in heavier smokers and reduced following quitting.Further large prospective studies could characterize this more precisely by more detailed assessment of smoking history and by more fully accounting for the range of other factors known to be related to type 2 diabetes.Care should be taken to determine the accuracy of all the data used, and to assess the effect that any possible inaccuracy might have on the estimated association.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Barbara Forey for assistance with classification of studies, Jan Hamling,John Hamling and John Fry for assistance in conducting the analyses described and producing the figures, and Yvonne Cooper and Diane Morris for typing various drafts of this paper.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年2期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年2期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Effectiveness and safety of sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy:An opinion review

- Chinese research into ulcerative colitis from 1978 to 2017:A bibliometric analysis

- Single-balloon and spiral enteroscopy may have similar diagnostic and therapeutic yields to double-balloon enteroscopy:Results from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective studies

- Utility of gastrointestinal ultrasound in functional gastrointestinal disorders:A narrative review

- Treatment strategies and preventive methods for drug-resistant Helicobacter pylori infection

- Helicobacter pylori and gastric cardia cancer:What do we know about their relationship?