Altered microRNA expression in animal models of Huntington’s disease and potential therapeutic strategies

Bridget Martinez , Philip V. Peplow

Abstract A review of recent animal models of Huntington’s disease showed many microRNAs had altered expression levels in the striatum and cerebral cortex, and which were mostly downregulated. Among the altered microRNAs were miR-9/9*, miR-29b, miR-124a, miR-132, miR-128, miR-139, miR-122, miR-138, miR-23b, miR-135b, miR-181 (all downregulated) and miR-448 (upregulated), and similar changes had been previously found in Huntington’s disease patients. In the animal cell studies, the altered microRNAs included miR-9, miR-9*, miR-135b, miR-222 (all downregulated) and miR-214(upregulated). In the animal models, overexpression of miR-155 and miR-196a caused a decrease in mutant huntingtin mRNA and protein level, lowered the mutant huntingtin aggregates in striatum and cortex, and improved performance in behavioral tests.Improved performance in behavioral tests also occurred with overexpression of miR-132 and miR-124. In the animal cell models, overexpression of miR-22 increased the viability of rat primary cortical and striatal neurons infected with mutant huntingtin and decreased huntingtin -enriched foci of ≥ 2 μm. Also, overexpression of miR-22 enhanced the survival of rat primary striatal neurons treated with 3-nitropropionic acid. Exogenous expression of miR-214, miR-146a, miR-150, and miR-125b decreased endogenous expression of huntingtin mRNA and protein in HdhQ111/HdhQ111 cells. Further studies with animal models of Huntington’s disease are warranted to validate these findings and identify specific microRNAs whose overexpression inhibits the production of mutant huntingtin protein and other harmful processes and may provide a more effective means of treating Huntington’s disease in patients and slowing its progression.

Key Words: animal model; cerebral cortex; huntingtin; Huntington’s disease; microRNA;neurodegeneration; striatum; therapeutic strategies

Introduction

A genetic mutation of thehuntingtin(HTT) gene causes Huntington’s disease (HD), with a cytosine-adenine-guanine trinucleotide (CAG, which encodes glutamine) expanded repeat at exon 1, leading to a polyglutamine (polyQ)expansion in the N-terminal regions of huntingtin (HTT)protein (Macdonald et al., 1993). Misfolding and aggregation of mutant huntingtin (mHTT) as well as age-related neurodegeneration results from this polyQ expansion. CAG repeat lengths of 6-35 are found in unaffected individuals,while HD individuals have repeat lengths > 36 on oneHTTallele, with CAG repeat length inversely correlated with the age of disease onset (Andrew et al., 1993; Orr and Zoghbi, 2007). HTT is converted from a neuroprotective to a neurotoxic protein by the polyQ expansion (Cattaneo et al.,2005). HTT may be involved in neurodevelopment, regulation of apoptosis, control of brain-derived neurotrophic factor(BDNF) production, vesicular and mitochondrial transport,neuronal gene transcription, and synaptic transmission(Cattaneo et al., 2005; Zuccato et al., 2010). Despite HTT expression in neurons throughout the brain, GABAergic medium spiny striatal neurons (MSN) and cortical neurons are the most vulnerable in HD individuals (Fusco et al.,1999). The progressive loss of cortical and striatal neurons causes cognitive defects, and motor control dysfunction including chorea (involuntary movements). However, there is wide variability in polyQ length, age of onset, and degree of symptoms (Cajavec et al., 2006). Most HD patients have expanded polyQ repeats of 38-55 glutamines and exhibit lateonset neurological symptoms around 30-50 years of age, with death usually occurring within 15 years after disease onset(Melone et al., 2005). Longer expansions (> 55 CAG repeats)may result in juvenile-onset HD (only about 6% of all HD cases) (Harper, 1996; Quarrell et al., 2012).

HTT interacts with the essential transcriptional repressor REST (Repressor Element 1 Silencing Transcription Factor)in neurons (Zuccato et al., 2003; Ooi and Wood, 2007). In unaffected individuals, wild type HTT sequesters REST in the cytoplasm of neurons. However, in HD individuals, this interaction is inhibited by the polyQ expansion of mHTT, with abnormally high levels of REST accumulating in the nucleus of HD neurons and leading to increased transcriptional repression of REST target genes, includingBDNF(Zuccato et al., 2007). Decreased survival of striatal neurons occurs due to the lowered levels of BDNF. Several neuronal microRNAs(miRNAs) are regulated by REST (Conaco et al., 2006), and have altered expression levels in HD patients (Johnson et al.,2008). Also, miR-9/miR-9*(miR-9-5p/miR-9-3p) regulates REST and CoREST and is downregulated in HD (Johnson et al., 2008; Packer et al., 2008). These findings suggest that dysregulation of neuronal miRNAs might be involved in HD pathogenesis. MiRNA dysregulation has been reported in HD patients, transgenic HD mice, and inin vitroexperimental models (Packer et al., 2008; Marti et al., 2010; Gaughwin et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011; Jin et al., 2012; Jovicic et al., 2013;Soldati et al., 2013).

A promising approach to delay the progression of HD is RNA interference (RNAi), as it can suppress the expression of mHTT at the post-transcriptional level (Boudreau et al., 2009; Drouet et al., 2009; Fiszer et al., 2011). MiRNA is one of the RNAi regulatory pathways and downregulates gene expression by binding to complementary sequences in the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of target mRNAs, further inhibiting protein translation (Didiano and Hobert, 2008; Williams, 2008).MiRNAs were shown to be involved in neuronal development and several neurodegenerative processes (Iyengar et al., 2014;Singh et al., 2014). Furthermore, miRNAs can regulate disease progression in HD (Buckley et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2013;Maciotta et al., 2013), and may be a promising therapeutic strategy.

Experimental Models of Huntington’s Disease

In vivo animal models

Animal models that mimic the clinical and neurobiological symptoms of HD can be used to further investigate the molecular pathogenesis of HD. They can also be used in the development of therapeutic strategies for HD, and evaluating the efficacy and safety of potential new drugs. These models can be grouped into three main classes: mitochondrial toxin models, excitotoxic models, and genetic models (Saxena,2013; Chang et al., 2015; Kaur et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2020).

Mitochondrial toxin models

Mitochondrial toxins include 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP) and malonic acid, and administering these compounds to both rats and primates causes striatal lesions that resemble clinical HD. They inhibit mitochondrial complex II enzyme (succinate dehydrogenase) and cause a reduction in ATP levels.

Chronic administration of 3-NP causes prolonged energy deficiency by mitochondrial dysfunction and mimics all pathophysiological features of HD, including degeneration of GABAergic MSNs of striatum. In rats, 3-NP-induced lesions in the basal ganglia resulted in enhanced N-methyl-D-aspartate(NMDA) receptor binding, decreased ATP, calcium overload,excitotoxic events, and neuronal death. Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress are correlated with excitotoxic cell death. Rats are more sensitive than mice to 3-NP treatment. As 3-NP readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, it can be systemically administered by subcutaneous osmotic pump and subcutaneous or intraperitoneal injection to rats, mice, and nonhuman primates.

Malonic acid does not cross the blood-brain barrier, but causes motor impairment and neuronal pathology similar to HD on intrastriatal administration to rodents. Malonic acid causes dose-dependent neurotoxicity, leading to neuronal depolarization and secondary excitotoxicity.

Excitotoxin models

Excitotoxicity is pathologic neurodegeneration caused by very high activation of non-NMDA and NMDA glutamate receptors and also voltage-dependent ion channels. Increases in intracellular Ca2+concentration and Ca2+-activated enzymes such as proteases, phospholipases, and endonucleases further promote the degradation of various cell components and neuronal death. Excitotoxic agents include kainic acid and quinolinic acid which bind to non-NMDA and NMDA receptors,respectively, on striatal neurons.

Kainic acid administration causes increased production of ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuronal apoptosis in many brain regions. Kainic acid induces abnormal behavioral events characterized by epileptiform seizures followed by neurodegeneration in specific brain regions including hippocampus, cortex, thalamus, and amygdala.

Quinolinic acid causes degeneration of GABAergic and substance P-containing neurons, with comparative sparing of NADPH-diaphorase and cholinergic neurons, which are found to be spared in HD. Quinolinic acid cannot cross the bloodbrain barrier and is, therefore, administered directly into the striatum. Quinolinic acid-induced excitotoxin lesions in the monkey comprise a nonhuman primate model that has the neurological and clinical features of HD.

Advantages of the toxin models are the pronounced cell death in the striatal brain region; the symptoms produced are analogous to HD pathology; they enable a further investigation of various mechanisms involved in HD pathogenesis (e.g., ROS formation, protease activation etc.); they allow for examining neuroprotective and neurorestorative therapies for HD; they are easily established in research laboratories; and they are more economical compared to other models. Disadvantages are production or misfolding of mHTT does not occur; in these toxin models cell death occurs immediately and is not dependent on mHTT, whereas in clinical HD the beginning of cell death is progressive and onset age is inversely proportional to the number of CAG repeats.

Genetic models

These comprise transgenic models and knock-in models.Transgenic models include fragment models like R6/1, R6/2,and full-length models such as BACHD, YAC128. Knock-in models include Hdh/Q72-80 and CAG140.

Transgenic mouse models:RD/1 and R6/2 transgenic mouse models were developed in 1996, with RD/2 mice being the most extensively studied model of HD. They both express exon 1 of human HTT with about 115 and 150 CAG repeats,respectively, under the control of the humanHTTpromoter(Mangiarini et al., 1996). A severe phenotype develops in R6/2 mice, with motor deficits evident at 5-6 weeks and often do not survive more than 13 weeks. The onset of behavioral changes in R6/1 mice is generally delayed by several weeks,and the progression of the severity of symptoms is slower (Li et al., 2005). The early death and severe phenotype makes R6/2 mice a plausible model for juvenile-onset HD, and indicates the toxicity of the N-terminal fragment of mHTT with a large polyQ repeat (Li and Li, 1998; Tang et al., 2011).Nuclear inclusions and aggregates are consistently formed from transgenic N-terminal mHTT in R6/2 mice, and led to the finding of similar inclusions in the postmortem brains of HD patients (DiFiglia et al., 1997; Gutekunst et al., 1999; Schilling et al., 2007; Landles et al., 2010). R6/2 mice mimicked human HD pathology in many respects but showed no apoptotic neuronal death, which differed from the extensive neuronal loss observed in the striatum and cortex of HD patients(Turmaine et al., 2000). This may be due to the early death of R6/2 mice (Menalled and Chesselet, 2002).

Transgenic mice expressing different N-terminal mHTT fragments provided further proof that the N-terminal mutant HTT is toxic. N171-82Q transgenic mice express the first 171 amino acids with 82 glutamines in the polyQ domain under the control of the mouse prion promoter and show progressive neurological phenotypes and early death, often occurring at 4-6 months of age (Schilling et al., 1999). Agedependent formation of HTT aggregates in neuronal cells occurs in these mice, consistent with N-terminal mHTT having an altered conformation leading to protein aggregation (Perutz et al., 1994; Davies et al., 1997).

Transgenic mice expressing full-length mHTT with expanded polyQ repeats provided further evidence indicating the toxicity of N-terminal mHTT. The most extensively studied of these HD mice are BACHD with 97 CAG/CAA mixed repeats and YAC128 with 128 CAG pure repeats in human HTT (Slow et al., 2003; Gray et al., 2008). BAC and YAC HD mice show selective atrophy in the striatum and cortex together with progressive motor deficits, thus exhibiting to some extent the regional selectivity of adult-onset HD. Differing from YAC128 mice, BACHD mice express a higher level of HTT but show fewer aggregates. Body weight gain is a shared phenotype in human HTT genomic transgenic mice, which is not found in HD patients (Pouladi et al., 2010).

Although several transgenic mouse models of HD have been extensively studied, none of them show the robust neurodegeneration observed in the brains of HD patients.The aging process is quite different between small and large animals, and mHTT may accumulate or be cleared differently in the brains of different species, thereby contributing to different pathologies in rodents and large animals. Transgenic HD rhesus monkeys express exon 1mHTTwith 84Q under the control of the human ubiquitin promoter (Yang et al.,2008). HD transgenic monkeys with 84Q die postnatally, and this early death is associated with the levels of mHTT (Yang et al., 2008). Some transgenic monkeys developed key HD features including dystonia, chorea, and seizure (Yang et al.,2008), which have not been replicated in mouse models or other small animal models. Similar to the brains of HD mouse models and patients, HD monkey brains showed abundant HTT aggregates in neuronal nuclei and neuronal processes.As degeneration of axons and neuronal processes occurs in the absence of obvious cell body degeneration in transgenic HD monkeys (Wang et al., 2008) neuronal degeneration in HD may start from neuronal processes.

Knock-in mouse models:Knock-in (KI) models with expanded CAG repeats or humanmHTTexon 1 replacing the corresponding sequences in the endogenous murineHTTgene locus have been produced (Shelbourne et al., 1999;Wheeler et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2001; Menalled et al., 2003;Heng et al., 2008). Also a series of mHTT-KI models with increasing polyQ length repeats 111, 140, 150, and 175 are available (Wheeler et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2001; Menalled et al., 2003; Heng et al., 2007; Woodman et al., 2007; Heikkinen et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2020). Late-onset of phenotype and progressive but mild pathology were found in these HD KI mice (Shelbourne et al., 1999; Wheeler et al., 2000), and many behavioral abnormalities were similar to transgenic mouse models but much milder (Woodman et al., 2007).Although not developing phenotypes as severe as transgenic mice expressing N-terminal mHTT, HD KI mice show the preferential accumulation of mHTT in striatal neurons that are mostly affected in HD, which is an important pathological change seen in the brains of HD patients (Lin et al., 2000;Wheeler et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2001).

In vitro animal cell models

These models include striatal cell lines that express wild type and mutant HTT, and also induced pluripotent and neuronal stem cells (Nekrasov et al., 2016; Szlachcic et al., 2016, 2017).

STHdh cells

STHdhstriatal cell lines were produced from a HD KI mouse embryo model (Trettle et al., 2000) carrying theHdhgene(mouse HD gene homologue) with a chimeric exon 1(Menalled, 2005) and characterized by a mild behavioral phenotype and neuropathological features (Wheeler et al.,2002). These cell lines are from striatal primordia (Trettle et al., 2000) and express wild type and mHTT at endogenous levels (Wheeler et al., 2000). Comparing immortalized striatal precursor cells from wild type mice (STHdhQ7/Q7cells) to precursor cells derived from homozygousHdhQ111 knock-in mice (STHdhQ111/Q111cells) has led to differences in several HDassociated cellular pathways being discovered or confirmed e.g., HTT involvement in calcium handling deficits and mitochondrial dysfunction (Gines et al., 2003a; Choo et al.,2004; Milakovic and Johnson 2005; Seong et al., 2005; Oliveira et al., 2006) or effects on various signaling cascades (Gines et al., 2003b; Xifró et al., 2008; Ferrante et al., 2014). Studies with these cells have indicated that specific stress pathways including elevated level of p53 protein, endoplasmic reticulum stress response, and hypoxia may play important roles in HD(Trettel et al., 2000). Whereas REST is largely cytoplasmic inHdhQ7/Q7cells, inHdhQ111/Q111cells it is mainly nuclear, leading to repression of its target genes (Zuccato et al., 2007; Solidatiet al., 2011). These cells have been shown to be ideal for analyzing the contribution of REST to gene expression changes in HD. Despite the undoubted usefulness and importance of the STHdhcell line model, differences have been reported in size (Milakovic and Johnson, 2005), shape (Reis et al., 2011)and proliferation rate (Singer et al., 2017), and might be confounding factors. This could make interpretation of study outcomes difficult due to introducing factors that cannot be properly controlled for.

iPSC and NSC cells

New cellular models include induced pluripotent and neuronal stem cells (iPSCs and NSCs, respectively) (Mattis and Svendsen, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Wiatr et al., 2018). The YAC128 and wild type iPSCs were generated from adult skin fibroblasts using a five-factor (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, cMyc, Lin28)piggyBac transposon-based system (Yusa et al., 2009, 2011).NSCs have been derived from mouse iPSCs (Karanfil and Bagci-Onder, 2016). In addition, neural progenitor cells have been established from monkey iPSCs that can differentiate into GABAergic neuronsin vitro(Cho et al., 2019). Similar molecular changes were observed in the iPSC stage in both YAC128 mouse and juvenile HD patient-derived cells (Szlachcic et al., 2015). These included decreased mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling activity, increased expression of the antioxidative protein superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), and decreased expression of the p53 protein which interacts with HTT and is involved in the above pathways (Szlachcic et al.,2015).

MicroRNAs in Animal Models of Huntington’s Disease

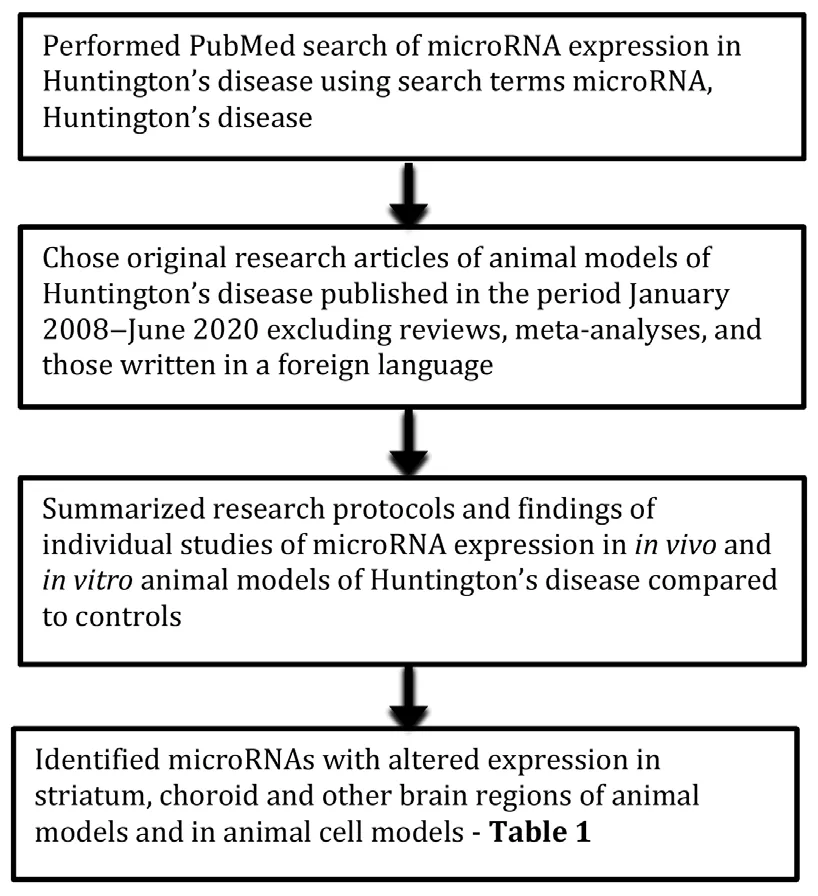

A PubMed search was performed for articles published during January 2008-June 2020 on levels of miRNA expression inin vivoandin vitroanimal models of HD to determine which ones are dysregulated in HD. Also, these articles were examined for whether overexpression or suppression of specific miRNAs could alleviate HD and thereby serve as therapeutic targets.The steps involved in the review and its contents are shown(Figure 1). A total of 17 articles were found for the review of which 3 had performed bothin vivoandin vitrostudies, 10 had carried out solelyin vivostudies, and 4 had performedin vitrostudies only.

In vivo animal studies

Figure 1 |Flow chart of article screening.

Spronck et al. (2019) performed intrastriatal injection of an adeno-associated virus expressing a miRNA targeting human HTT (AAV5-miHTT) at low, medium and high doses in both hemispheres of Q175 KI and wild type (WT) littermate male mice at 3 months of age. An engineered mmu-pre-miR-155 scaffold had embedded miHTT sequences (Miniarikova et al.,2016). Q175 KI and WT mice were injected with vehicle and served as a control group. At 12 months after intrastriatal injection of AAV5-miHTT, a significant dose-dependent average decrease of mHTT protein of up to 39% in the striatum and up to 13% in the cortex of Q175 KI mice was found. Staining with an antibody specific for aggregated HTT (Gutekunst et al., 1999) indicated a decrease of mHTT aggregates in the striatum and cortex of Q175 KI mice treated with the high dose of AAV5-miHTT compared with vehicle-treated Q175 KI mice. Treatment with AAV5-miHTT led to sustained HTT protein lowering and decreased aggregation in this mouse HD model. R6/2 mice were injected at 4 weeks of age with AAV5-miHTT using the same procedure and doses as for the Q175 KI mice. R6/2 mice began losing body weight around 10 weeks of age. Treatment with the high dose of AAV5-miHTT resulted in a significantly higher body weight in R6/2 mice compared with untreated R6/2 mice at 10, 11, 13, 15-19, and 21 weeks of age. Motor coordination on the rotarod was significantly improved in the high dose AAV5-miHTT group compared with vehicle-treated R6/2 mice. The median survival of R6/2 mice treated with a low dose was increased by 26.5 days, whereas R6/2 mice treated with the high dose had an increase of 29 days (median survival 149 days) compared with untreated R6/2 mice (median survival 120 days).

In a study by Langfelder et al. (2018), male mice of seven heterozygous KI lines expressing 20, 50, 80, 92, 111, 140,175 CAG repeats were crossed with female C57BL/6J mice.Guidelines for selecting animals included numbers of animals from the litters contributing to the experimental groups and a body weight > 11 g (female) and > 13 g (male) by 5 weeks of age. In the first phase of the study, four female and four male heterozygous mice from each Q20, Q89, Q92, Q111,Q140 and Q175 lines plus WT control littermates of Q20 mice at age 2, 6 and 10 months were profiled using deep microRNA sequencing. The Q20 mice had a repeat length that approximated to the average humanHTTrepeat length and were considered controls. In the second phase, four female and four male animals from Q20, Q50, Q92 and Q140 phenotypes at age 2, 6 and 10 months plus WT littermates of Q20 and Q50 lines were profiled. Pronounced age- and CAGlength-dependent increases were observed in differentially expressed (DE) miRNAs in the striatum and to a lesser extent in the cortex, cerebellum, and hippocampus. At 2 months of age, a modest number of DE miRNAs were found across most of the tissues, but the observed differential expression of these miRNAs did not appear to be progressive with increasing CAG length. In contrast, in the 6- and 10-month striatum there was a relatively large number of DE miRNAs that increased with CAG length. This was especially noticeable in 10-month striatum, where there were no DE miRNAs in Q80, 2 in Q92, 34 in Q111, 58 in Q140, and 68 in Q175. In the cerebellum, significantly DE miRNAs were only detected in Q140 (13 at 10 months) and Q175 lines (1, 69, and 79 at 2,6 and 10 months, respectively). In the cortex, most of the DE miRNAs were found in Q175 samples (8 at 6 months and 33 at 10 months): there were only a small number of DE miRNAs in lower CAG length samples (3 and 7 in Q40 and Q92 at 2 months, 6 in Q92 at 6 months). In the hippocampus, most DE miRNAs were found in Q175 samples: 16 and 43 at 6 and 10 months, respectively. The miR-212/miR-132 cluster and miR-218 were downregulated in the striatum. There were only three miRNAs (miR-484, miR-212, and miR-6944) that were commonly dysregulated across all four brain regions. A single miRNA, miR-484 was differentially expressed (downregulated with increasing CAG length) across all tissues in the first phase of the study and striatum in the second phase and changed in the same direction with Q across all 9 data sets.

Reynolds et al. (2018) using qPCR showed that miR-34a-5p expression in the brain (cerebellum excluded) of R6/2 male mice with CAG repeat length of 144 was significantly lower compared to WT littermate mice at 5, 8 and 11 weeks of age, and the difference between R6/2 CAG144 and WT mice increased with age. A significant effect of the HD phenotype onSirt1mRNA expression was observed in brain tissue, with increased expression found in R6/2 CAG144 males regardless of age, consistent with miR-34a-mediated repression of SIRT1.Measurement of miR-34a-5p expression in brain tissue from early symptomatic (8-week-old) R6/2 female mice with 182 CAG repeat length, an age when significant motor symptoms were present but no weight loss was yet seen, showed no statistically significant difference compared to WT mice.Likewise, in late-symptomatic (12-week-old) R6/2 CAG182 mice, miR-34a-5p expression was not significantly different in either female or male mice compared to WT mice.Sirt1mRNA levels were significantly upregulated in 8-week-old R6/2 CAG182 female mice. However,Sirt1mRNA expression in 12-week-old female and male R6/2 CAG182 mice did not differ significantly from WT littermates. SIRT1 protein levels were significantly increased in 8-week-old R6/2 CAG182 females and in 12-week-old R6/2 CAG182 females and males.

By RT-PCR, Fukuoka et al. (2018) showed the expression of miR-132 was significantly decreased in the striatum and cerebral cortex of 9-week-old R6/2 CAG124 male mice compared to WT male littermates. To determine the effect of supplying miR-132 to the brain and compensate for the decrease of miR-132 in R6/2 brains, constructed miR-132-expression adeno-associated viruses (AAV9_miR-132) and negative control viruses (AAV9_miR-Neg) were introduced into the striatum of ~3 week-old R6/2 and WT mice, the age when the marked difference in miR-132 levels began to appear in the R6/2 mice. Following virus administration, miR-132 levels returned to normal levels in the striatum of AAV9_miR-132-treated R6/2 mice. An increase in miR-132 was also detected in the cerebral cortex and midbrain of AAV9_miR-132-treated R6/2 mice, probably due to diffusion of AAV9_miR-132 viruses. Rotarod and open-field test showed a definite amelioration in AAV9_miR-132-treated R6/2 mice. Moreover,AAV9_miR-132-treated R6/2 mice had a significant increase in survival compared to AAV9_miR-Neg-treated R6/2 mice. Thus,miR-132 supplementation was successful in improving motor function of R6/2 mice and prolonging their life, and therefore in slowing down disease progression in R6/2 mice. MiR-132 supplementation had little effect on the expression of mHTTs and their inclusion body formation in AAV9_miR-132-treated R6/2 mice.

Lee et al. (2017) examined exosome delivery of miR-124 into the striatum of 6-week-old R6/2 mice. At 1 week later, the exosome-miR-124 injected mice had slightly higher levels of miR-124 expression in the brain compared to the control (nontreated) R6/2 mice, but not significantly different. However,the level of REST protein in the brain (the key target protein of miR-124) was significantly lower in the exosome-miR-124 treated R6/2 mice than in control R6/2 mice. There was no difference in rotarod performance between the exosome-miR-124-treated R6/2 mice and the control R6/2 mice at 7 weeks of age.

Her et al. (2017) found no significant difference in the expression levels of synaptic proteins PSD95 and synaptophysin between miR-196a transgenic mice overexpressing miR-196a and non-transgenic mice, but VAMP1 was significantly increased in miR-196a transgenic mice compared to non-transgenic mice. Neuronal activity in the brains of these transgenic mice, determined by the detection of c-Fos (Zhang et al., 2002), showed miR-196a transgenic mice had significantly higher intensity of c-Fos signals in the brain. In addition, higher expression levels were found in miR-196a transgenic mice of calbindin D-28K,a marker related to neuronal activity and synaptic plasticity(Westerink et al., 2012). MiR-196a transgenic mice exhibited significantly greater abilities of learning and memory in the T-maze test but not in the novel object recognition test. There was a significant decrease of endogenous ran-binding protein 10 (RANBP10) in miR-196a transgenic mice, suggesting that miR-196a could bind to 3′ UTR of RANBP10 to suppress the expression of RANBP10. Decreased total neurite length occurred in RANBP10 transgenic mice, and a greater trend of RANBP10 expression was evident in R6/2 transgenic mice(Mangiarini et al., 1996).

Keeler et al. (2016) performed bilateral intrastriatal injection of AAV9-GFP-miRHttat 6 or 12 weeks of age in homozygous Q140/Q140 knock-in mice. AAV9-GFP-miRHttvector was engineered carrying GFP in tandem of an artificial miRNA against HTT embedded in the 3′ UTR of GFP. A miRNA miR-155(miRHtt) scaffold was embedded with the sequences targeting mouse HTT mRNA. At 6 months of age, the levels of mHTT mRNA in striatum were 40-50% lower in mice injected with AAV9-GFP-miRHttvector at 6 or 12 weeks of age compared to control mice injected with AAV9-GFP. mHTT protein in mice injected with AAV9-GFP-miRHttvector at 6 or 12 weeks of age was reduced by 40% and 25%, respectively, compared to control mice injected with AAV9-GFP. Using a branched DNAbasedin situhybridization method to investigate decrease of striatal HTT at the cellular level, a marked shift was seen in the distribution of HTT mRNA foci in MSNs of mice injected with AAV9-GFP-miRHtt. The percentage of total MSNs with 0-2 foci was significantly higher in the AAV9-GFP-miRHttgroup compared to control groups; conversely, the percentage of MSNs with ≥ 5 foci was significantly lower in AAV9-GFPmiRHttgroup compared to controls. Treatment of Q140/Q140 mice with AAV9-GFP-miRHttincreased the percentage of MSNs with no HTT mRNA foci to 14-20%, depending on the striatum region analyzed. No difference was found in Iba1 immunoreactivity in the striatum of AAV9-injected mice compared to non-injected controls, suggesting an absence of an inflammatory response. The mean striatal crosssectional area in AAV9-GFP-miRHttmice at 12 weeks of age was decreased by 10% compared to non-injected controls.

Injection of miR-124 into the striatum of R6/2 mice 8 weeks of age by Liu et al. (2015) was found to significantly improve rotarod test performance at 10 and 11 weeks of age compared to vehicle injection for control mice (N/C miRNA).There was no significant difference of weight loss between the miR-124 injected R6/2 mice and the N/C miRNA-injected R6/2 mice. The expression levels of neuroprotective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α and BDNF were increased and SRY-box transcription factor 9, the repressor of cell differentiation, was decreased in miR-124-injected R6/2 mice compared with the N/C control-injected R6/2 mice.

Kocerha et al. (2014) found a significant increase of mHTT aggregates in the frontal cortex of HD rhesus monkeys that were miscarried or delivered at full term compared to control animals. Caspase-3 positive cells were detected by immunostaining in the frontal cortex of HD4, HD7 and HD8 monkeys, with significantly fewer positive cells observed in control monkey brains. An increased number of astrocytic positive cells with intense GFAP immunostaining was found in the frontal cortex of HD monkeys compared to control monkeys. Expression of GFAP protein was significantly increased in the frontal cortex of HD7 and HD8 compared to control monkeys. With miRNA array profiling, 11 miRNAs were significantly dysregulated in HD monkeys, 2 were upregulated and 9 were downregulated compared to controls.By qPCR analysis, miR-194 was significantly upregulated while miR-181c, miR-128a, and miR-133c were significantly downregulated in the brains of HD monkeys compared to control animals.

Cheng et al. (2013) generated miR-196a transgenic mice via lentiviral transgenesis and by breeding withGFP-HTT(GHD) transgenic mice obtained four groups of mice: double transgenic mice (D-Tg) carryingmHTTand miR-196a, GHD transgenic mice, 196a transgenic mice, and WT mice. Lower expression levels of mHTT mRNA and protein were found in brain samples of D-Tg transgenic mice at 1 month of age compared to GHD transgenic mice, and there was a significantly higher expression of miR-196a in D-Tg transgenic mice compared to GHD transgenic mice. Brain samples from D-Tg and GHD transgenic mice at 1 and 12 months of age had an increase of aggregated mHTT in GHD mice at 12 months of age, whereas D-Tg mice had much fewer mHTT aggregates at 1 and 12 months of age, implying that miR-196a inhibited the expression of mHTTin vivo. Severe pathological aggregates were observed in different brain regions, such as the cortex and striatum, in GHD transgenic mice at 12 months of age,whereas much fewer aggregates were seen in D-Tg transgenic mice. Comparable behavioral phenotypes were observed in the groups at 4 and 8 months of age; however, a worsening performance was observed in GHD mice at 12 months of age, whereas D-Tg mice had a similar performance to that of 196a transgenic mice and WT mice. These studies indicated that miR-196a could improve molecular, pathological and behavioral phenotypesin vivo.

Jin et al. (2012) used RT-PCR to determine miRNA levels in cerebral cortex and striatum samples of N171-82Q HD male mice. MiR-200a and miR-200c were significantly upregulated in the cortex and striatum of 12-week-old N171-82Q mice.The levels of miR-200a and miR-200c in the cortex and striatum of HD mice were significantly increased at the early stage of disease in 8- and 12-week-old N171-82Q mice, but did not differ at the later stage of disease in 18-week-old N171-82Q mice, compared to age-matched WT mice. The mRNAs encoding ATP2A2, ATCXN, and NRXN1 are shared targets for miR-200a and miR-200c. These downregulated target genes of miR-200a and miR-200c have been suggested to play important roles in synaptic function, axonal trafficking,neurotransmitter release, neurogenesis, and neuronal survival. It was suggested that upregulation of miR-200a and miR-200c might repress these genes involved in progressive neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration in HD.

Using RT-PCR, Lee et al. (2011) showed that nine miRNAs were commonly downregulated in striatum of YAC128-12months and R6/2-10weeks mice: miR-22, miR-29c, miR-128, miR-132,miR-138, miR-218, miR-222, miR-344, miR-674*. No miRNAs were commonly downregulated in YAC128-5months and R6/2 mice. However, four miRNAs miR-34b-3p, miR-207, miR-448,miR-669c were commonly upregulated in YAC128-5months and R6/2 mice, and one miRNA miR-18a*was upregulated in both YAC128-5months and YAC128-12months mice. No miRNA was commonly upregulated in both YAC128-12months and R6/2 mice. In male Lewis rats 12 weeks of age treated with 3NP via a subcutaneous Alzet osmotic minipump, there were fewer miRNAs that changed during the 3NP-induced striatal degeneration than in the transgenic mice. Three miRNAs miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-429 were commonly upregulated in the 3NP-Day3 and 3NP-Day5 groups, with the levels being highest in the 3NP-D3 group. One miRNA miR-349 was upregulated in 3NP-D1 and 3NP-D5 groups. Two miRNAs miR-181 and miR-96 were commonly downregulated in the 3NP-D1 and 3NP-D3 groups. No miRNAs were commonly downregulated or upregulated among YAC128-12months mice, R6/2 mice, and 3NP-D5 rats.

Using qPCR, Johnson et al. (2008) examined the levels of seven REST target miRNAs in the cortex of R6/2 mice at 12 weeks of age, and found four had significantly reduced expression,miR-29a, miR-124a, miR-132, and miR-135b. There were similar differences in miRNA expression in the hippocampus of the same animals. Among these dysregulated miRNAs were the important neuronal-specific miRNAs miR-124a and miR-132. To confirm the observed dysregulation of miRNAs in R6/2 brain and to investigate downstream effects of this, the levels of five target mRNAs of the dysregulated miRNAs were measured in the same R6/2 cortex samples. The target mRNAs were Atp6v0e, Vamp3, Plod3, Ctdsp1, and Itgb1. All of these five mRNAs had increased levels in R6/2 cortex, of which four were statistically significant. These findings were consistent with the observed decrease in miR-124a levels in R6/2 cortex.

In vitro animal cell studies

Her et al. (2017) examined mouse primary cortical neurons transfected withmiR-196a-DsRedthat carried the precursorhas-miR-196a-2under control of a human ubiquitin promoter and aRFPgene, and observed significantly more branches and greater neurite length in miR-196a neurons. In N2a mouse neuroblastoma cells overexpressing miR-196a there was an increased velocity of intracellular transport during anterograde but not retrograde transport compared to that of DsRed control. The expression level of endogenous RANBP10 was significantly decreased in miR-196a transfected cells.Significantly less branches and shorter neurite outgrowth in N2a cells and primary neurons resulted from overexpression of RANBP10-DsRed. The transport velocity during retrograde but not anterograde transport was significantly decreased by RANBP10. CotransfectingmiR-196a-GFPwithRANBP10-DsRedinto N2a cells showed that RANBP10 significantly blocked the function of miR-196a on total neurite length but not on branch numbers, suggesting RANBP10 was a critical regulator of miR-196a on neuronal morphology.

In an earlier study by Fu et al. (2015), total neurite outgrowth was significantly shorter in mouse neuroblastoma N2a cells transfected with HTT84Q (HD group) compared to cells transfected with HTT19Q group (control group), suggesting less neurite outgrowth under the HD conditions. Transfection with miR-196a significantly enhanced neurite outgrowth compared to the miR-NC transfection control group. N2a cells transfected with HTT84Q+miR-196a had significantly increased neurite outgrowth compared to cells transfected with HTT84Q+miR-NC.

Soldati et al. (2013) investigated whether abnormal repression of miRNAs in the presence of mHTT was due to increased levels of nuclear REST. Twenty mouse miRNAs with a known REST binding site within 100 kb, 9 mouse miRNAs with no known REST binding site but were downregulated in HD, and the mouse homologues of 12 human miRNAs with a REST binding site within 100 kb and were dysregulated in HD, were selected. Comparing the expression of these 41 miRNAs inHdh109/109cells relative toHdh7/7cells by RT-PCR showed that 15 were expressed at significantly lower levels: miR-9, miR-9*, miR-23b, miR-124, miR-132, miR-133a, miR-135b, miR-135b*, miR-139, miR-212, miR-222, miR-344, miR-153, miR-455, miR-137. Twelve of these miRNAs were significantly increased following REST knock-down: miR-9, miR-9*, miR-23b, miR-124, miR-132, miR-135b, miR-135b*, miR-212, miR-222, miR-153, miR-455, miR-137. Three of these upregulated miRNAs, miR-137, miR-153, and miR-455, were mouse homologues of human miRNAs with predicted REST binding sites 1859 bp, 7735 bp, and 859 bp from their transcriptional start sites, respectively. These three putative sites were tested for REST occupancy. Greater levels of REST occupancy were found at miR-137 and miR-153 inHdh109/109cells compared toHdh7/7cells, which was significantly decreased following REST knock-down, suggesting that REST was a direct regulator of these miRNAs in HD. This study showed that many of the dysregulated miRNAs in HD were directly repressed by increased levels of REST.

In a study by Jovicic et al. (2013), rat primary cortical and striatal neurons were infected with lentiviruses encoding the first 171 amino acids of WT or mHTT (HTT171-18Qvs. HTT171-82Q). The viability of both striatal and cortical neurons was significantly decreased by HTT171-82Q, but significantly restored by miR-22 overexpression. In parallel cultures immunostained with anti-HTT antibodies, the number of HTT-enriched foci of ≥ 2 μm was lowered by miR-22. Also,striatal neurons were treated with 3-NP for 48 hours with miR-22 overexpression versus a control comprising neuronal cells without miRNA overexpression. Although the miR-22-expressing vector modestly decreased neuronal viability(NeuN-positive cell count) compared to the non-treated control, reflecting toxicity of the lentiviral vector application,miR-22 overexpression significantly increased the survival of 3-NP treated neurons. Long-term culture of cortical neurons> 5 weeks (aging model) caused a significant decrease in the number of neurons, and long-term neuronal survival was significantly increased by miR-22 expression. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase 14/p38 activity was one of the neuroprotective capabilities of miR-22. Activation of effector caspases occurred in HTT171-82Q and 3-NP model,and was significantly inhibited by overexpression of miR-22.

By RT-PCR, Sinha et al. (2011) observed that the expression of miR-150, miR-146a and miR-125b was decreased while that of miR-214 was increased in STHdhQ111/HdhQ111cells compared to STHdhQ7/HdhQ7cells. Expression of exogenous miR-214, miR-146a, miR-150 and miR-125b downregulated the endogenous expression of HTT mRNA and protein. In an earlier study,Sinha et al. (2010) showed by RT-PCR that the expression of miR-9, miR-9*, miR-100, miR-125b, miR-135a, miR-135b,miR-138, miR-146a, miR-150, miR-181c, miR-190, miR-218,miR-221, miR-222, miR-338-3p was significantly decreased,whereas the expression of miR-145, miR-199-5p, miR-199-3p, miR-148a, miR-127-3p, miR-200a, miR-205, miR-214, miR-335-5p was significantly increased, in STHdhQ111/HdhQ111cells compared to STHdhQ7/HdhQ7cells. Expression of miR-299-5p,miR-323-3p, miR-154 was found only in STHdhQ111/HdhQ111cells.

Johnson et al. (2008) found that REST function was decreased by infectingHdhQ7/Q7cells with a recombinant adenovirus expressing a dominant-negative REST construct. By a modified RT-PCR assay and comparison with control adenoviral treated cells, miR-29a, miR-29b-1, miR-132, miR-135b were significantly upregulated upon loss of REST function.

Discussion

Studies with animal and cell models of HD have indicated that proteolysis of full-length HTT produces a number of small N-terminal HTT fragments that are misfolded into aggregates in axons and neurites (Yang and Chan, 2011; Chang et al.,2015). Behavioral symptoms in HD are preceded by various molecular changes, including deregulation of gene expression(Augood et al., 1997a,b) and histone modifications (Gray,2011). Understanding the deregulation of gene expression may indicate potential therapeutic strategies to inhibit the disease process in HD.

Clearance of the mHTT is the target of several potential disease-modifying therapies for HD (Ross et al., 2014). HTTlowering strategies such as antisense oligonucleotides(ASOs), RNAi, ribozymes, DNA enzymes, and genome-editing approaches (Aronin and DiFiglia, 2014) have been investigated by various groups. Binding of molecules to HTT mRNA to block translation into the toxic HTT protein may be a possible strategy for HTT lowering. MiRNAs are endogenous, singlestranded, noncoding RNA molecules, typically 22 nucleotides in length that negatively regulate gene expression. By binding to complementary sequences in the 3′-untranslated regions(3′-UTR) of target mRNAs, miRNAs induce mRNA degradation(Bagga et al., 2005) or inhibit translation (He and Hannon,2004; Meister, 2007). They are involved in basic cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis,and cell cycle regulation (Mens and Ghanbari, 2018). MiRNAs may have a key role in neuronal development as well as in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders (Bilen et al., 2006; Conrad et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2007; Trivedi and Ramakrishna, 2009). While a large number of studies have examined mRNA expression as markers of HD in postmortem human brains as well as in mouse models, comparatively little is known about changes in miRNA expression in HD patients or animal models. MiRNAs have been examined in several small studies performed on postmortem human tissue (Marti et al.,2010). Certain miRNAs could bind to HTT mRNA and inhibit its translation by the endogenous RNAi machinery (see Boudreau et al., 2011).

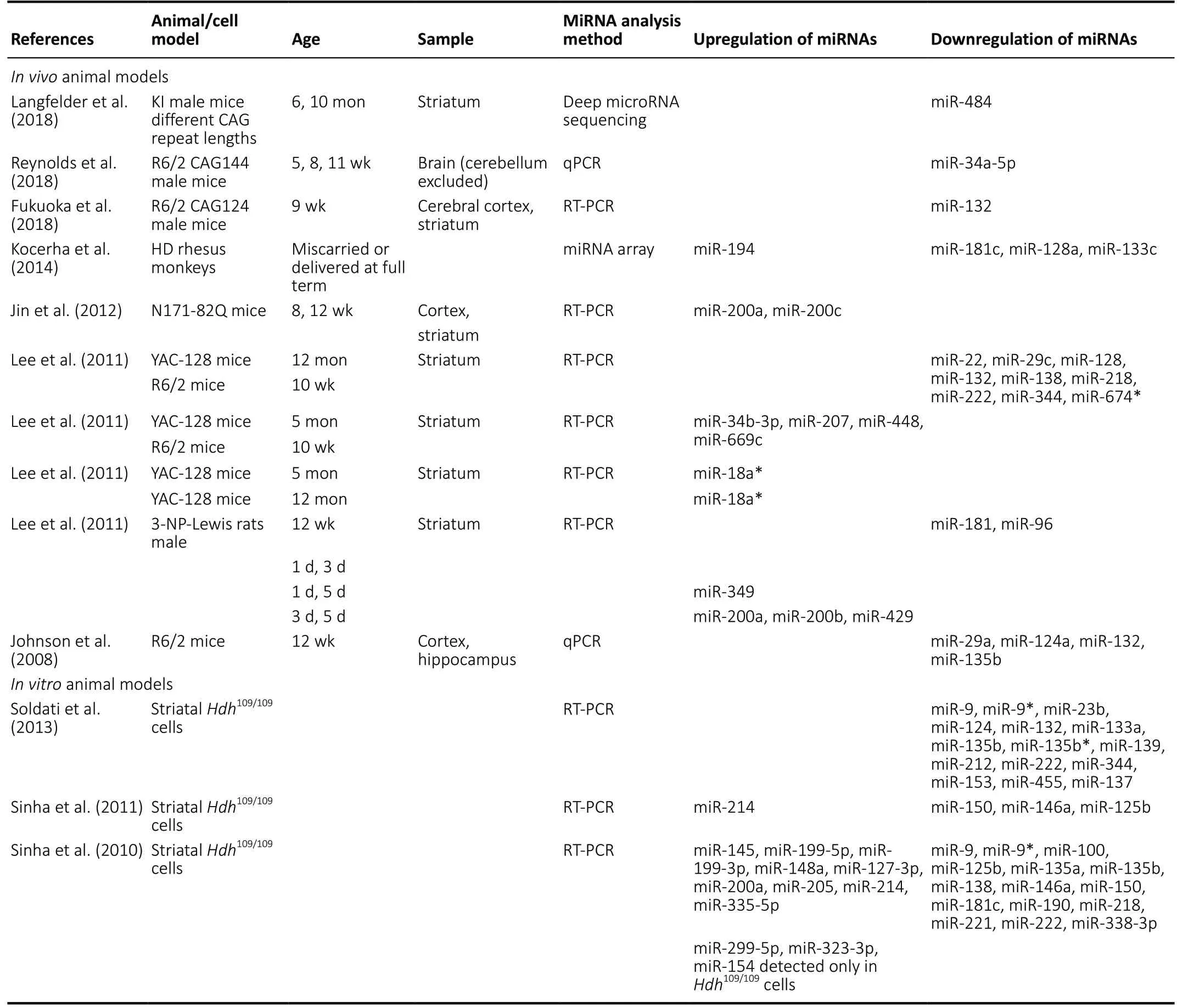

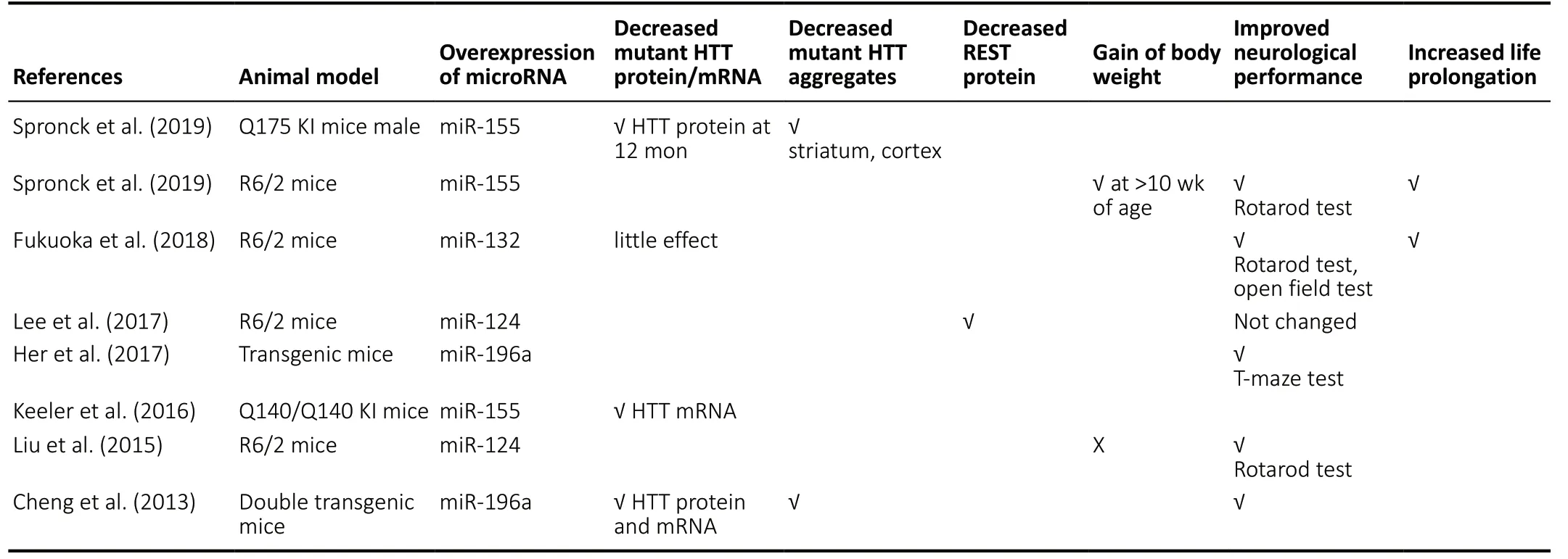

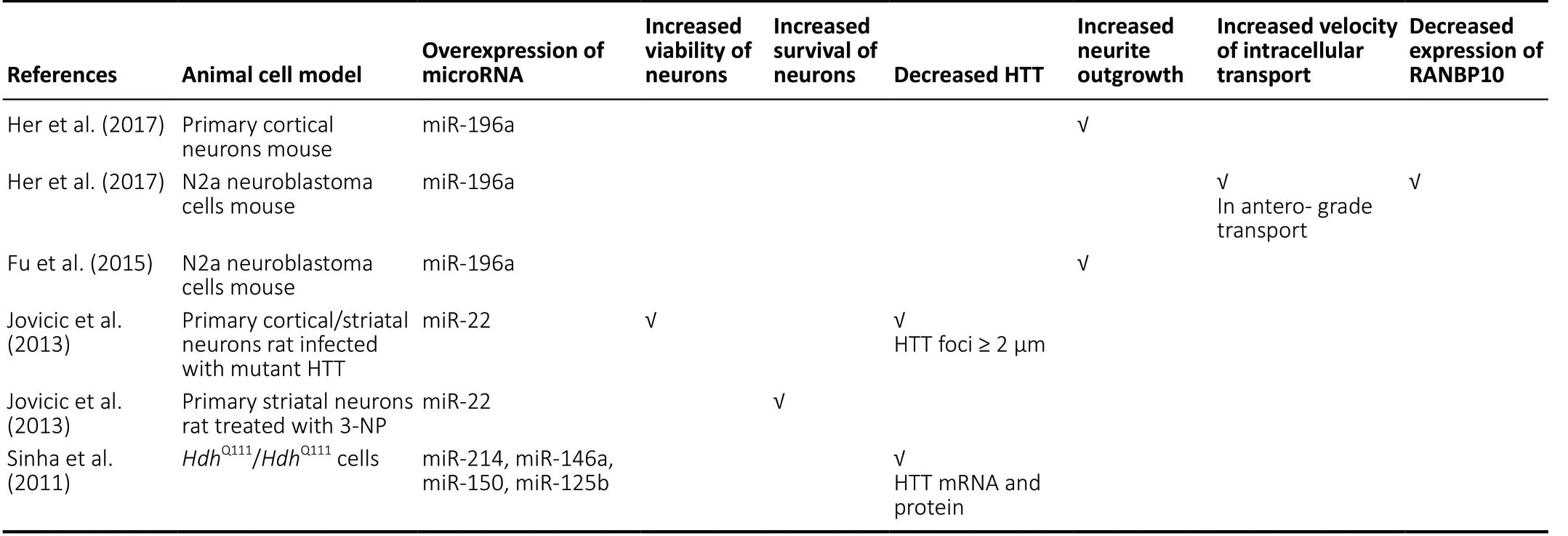

In the present review ofin vivoanimal studies, dysregulation of miRNAs was reported in brain tissues, principally striatum and cerebral cortex, of several different HD animal models. A large number of miRNAs were downregulated whereas only a small number were upregulated (Table 1). Among the miRNAs found to be downregulated in two or more of the studies were miR-132, miR-181, miR-128, miR-29, and the upregulated miRNAs included miR-200a. In thein vitroanimal cell studies,the downregulated miRNAs in two of the studies included miR-9, miR-9*, miR-135b, miR-222 while the upregulated miRNAs included miR-214 (Table 1). The downregulated miRNAs that were common in both thein vivoandin vitrostudies included miR-132, miR-181c, miR-133, miR-138, miR-218, miR-222,miR-344, while the upregulated miRNAs included miR-200a.Furthermore, in thein vivoanimal models, overexpression of miR-155 and miR-196a caused a decrease in mHTT at mRNA and protein level, lowered the mHTT aggregates in striatum and cortex, and improved the performance in behavioral tests. In addition, miR-155 overexpression resulted in a gain of body weight in R6/2 mice at > 10 weeks of age and increased life prolongation. Improved performance in behavioral tests was also found with overexpression of miR-132 and miR-124 (Table 2). Interestingly, in thein vitroanimal cell models,overexpression of miR-196a resulted in increased neurite outgrowth in mouse primary cortical neurons and N2a neuroblastoma cells, with increased velocity of anterograde intracellular transport in the latter. Overexpression of miR-22 increased the viability of rat primary cortical and striatal neurons infected with mHTT and decreased HTT foci ≥ 2 μm.Also, increased survival of rat primary striatal neurons treated with 3-NP occurred with overexpression of miR-22.HdhQ111/HdhQ111cells overexpressing miR-214, miR-146a, miR-150, or miR-125b had decreased HTT mRNA and protein level (Table 3).Previous studies had reported downregulation of specific miRNAs in the postmortem cortex/striatum of human HD patients such as miR-9/9*, miR-29b, miR-124a (Packer et al.,2008), miR-132 (Johnson et al., 2008), miR-128, miR-139, and miR-122 (Marti et al., 2010) which correlate with the findings in the reviewed animal studies. There were inconsistencies in the findings of the human studies as miR-29b was also reported to be upregulated in HD patients (Johnson et al.,2008). In a more recent study of differentially expressed miRNAs in the prefrontal cortex of human HD patients,downregulated miRNAs included miR-138, miR-132-3p, miR-23b, miR-135b, miR-181 and upregulated miRNAs included miR-448 (Hoss et al., 2015) which are in agreement with the animal studies. However, miR-29a was upregulated (Hoss et al., 2015) whereas it was downregulated in the animal studies. The function of many of these miRNAs in HD remains to be elucidated. However, a decrease of miR-132 has been shown to increase its targetp250GAP, encoding a member of the group of GTPase-activating proteins that inhibit neurite outgrowth, resulting in HD progression (Vo et al., 2005;Johnson et al., 2008).

At present there is no cure for HD and the only medication approved by the U.S. FDA, tetrabenazine or deutetrabenazine,is for the treatment of chorea in HD patients. Tominersen(RG6042) is an ASO that binds to the mHTT mRNA, targeting it for degradation, and can be administered via an intrathecal catheter in HD patients. A Phase 1/2 study has been performed in patients with early stage HD who were treated with tominersen or placebo for 13 weeks, and showed significant reductions in mHTT protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of tominersen-treated patients with a favorable safety and tolerability profile (Tabrizi et al., 2019; Rocha et al., 2020).It is now being investigated in a Phase 3 GENERATION HD1 study (ClinicalTrials.gov). A miRNA-based therapy may also provide a way of reducing mHTT protein in patients with HD.One possibility might be to use a single or combination of two or three of the miRNAs found to reduce mHTT mRNA and protein in the animal model studies e.g., chosen from miR-155, miR196a, miR-22, miR-214, miR-146a, miR-150,miR-125b. Moreover, administration of miR-124 could have a beneficial effect as it decreased REST protein expression. A Phase 1/2 clinical trial is underway to test AMT-130 delivered directly to the brain of patients with HD. AMT-130 consists of an AAV5 vector carrying an artificial miRNA specifically tailored to silence the HHT gene and inhibit the production of mHTT protein. The miHTT sequences were embedded in the engineered hsa-pre-miR-451a scaffold (Caron et al.,2020). In June 2020, it was announced the first two patients had been treated, one patient with AMT-130 and one patient who received the imitation surgery (http://uniqure.com/genetherapy/huntingtons-disease.php).

From a clinical viewpoint, a main disadvantage of ASOs and small interfering RNAs is the repeated dosing of patients,whereas AAV-mediated gene therapy (which includes RNAbased gene silencing) involves a one-time dosing strategy.Technological improvements have enabled ASO doses to be less frequent than in the past e.g., with nusinersen, a recently approved ASO as a treatment for spinal muscular atrophy, a patient would receive three intrathecal doses yearly and would be continued for life. By contrast, AVXS-101, a gene therapy treatment for spinal muscular atrophy type 1,has a therapeutic effect for up to 24 months after a single intravenous injection of an AAV9 vector (Mendell et al., 2017).The five adverse effects reported with AVXS-101 therapy consisted of asymptomatic liver enzyme elevations, and have been observed with other gene therapy trials (Nathwani et al., 2011, 2014). AAVs have proven to be safe in both animal and human studies (Colella et al., 2018). Intrathecal delivery of an AAV10 vector harboring a SOD1-targeting artificialmRNA was found to be a safe and effective means of silencingSOD1expression throughout the spinal cord in nonhuman primates (Borel et al., 2016, 2018). AAV vectors harboring a HTT-targeting artificial mRNA could be trialed in marmosets as a therapeutic procedure for HD. Transgenic marmosets expressing expanded CAG repeats have been successfully produced which recapitulated the common characteristics of human patients with polyQ disease, with no symptoms at birth but exhibiting progressive motor impairment within several months after the disease onset at 3-4 months of age(Tomioka et al., 2017). Methods for the design of artificial miRNAs against a target of choice, cloning these miRNAs into an AAV-based vector, and rapidly screening for highly efficient artificial miRNAs have been described recently (Borel and Mueller, 2019). Peripheral immune responses to AAV capsid are a major concern in clinical trials, as initiation or reactivation of a T cell response to AAV capsid as well as hightitre of neutralizing antibodies can prevent AAV transduction and vector readministration. In the study involving intrathecal delivery of an AAV10 vector harboring a SOD1-targeting artificial mRNA in macaques, a cellular immune response was present in some animals that was transient and did not persist a few months after gene transfer. A neutralizing antibody response to AAV10 occurred after intrathecal delivery and did not correlate with the cellular immune response (Borel et al.,2018).

Table 1 |Dysregulated microRNAs in in vivo and in vitro animal models of Huntington’s disease

Table 2 |Alterations in in vivo animal models of Huntington’s disease following overexpression of specific microRNAs

Table 3 |Alterations in in vitro animal cell models of Huntington’s disease following overexpression of specific microRNAs

In conclusion, animal models of HD show many of the changes in miRNA expression that have been reported in the striatum and cortex of HD patients. They have proven to be useful in testing possible therapies for HD such as tominersen (RG6042)and AMT-130 e.g., RG6042 was shown to delay disease progression and reverse disease symptoms in mouse models of HD (Huntington’s Disease News, 2019), while AMT-130 was shown to preserve cognitive function in a humanized mouse model of HD (Caron et al., 2020). This review underlies the importance and need for further studies with animal models of HD especially nonhuman primates, specifically testing AAV vectors carrying miRNAs to inhibit the production of mHTT protein and provide a more effective means of treating HD and slowing its progression.

Author contributions:All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial support:None.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articlesare distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2021年11期

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2021年11期

- 中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Mechanisms implicated in the contralateral effect in the central nervous system after unilateral injury: focus on the visual system

- Toward three-dimensional in vitro models to study neurovascular unit functions in health and disease

- Apolipoprotein A1, the neglected relative of Apolipoprotein E and its potential role in Alzheimer’s disease

- Oral frailty and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease

- Non-coding RNAs and other determinants of neuroinflammation and endothelial dysfunction:regulation of gene expression in the acute phase of ischemic stroke and possible therapeutic applications

- Mesenchymal stem cell treatment for peripheral nerve injury: a narrative review