The “July Eff ect” in the intensive care units revisited:A bi-institutional 6-year experience of 57,160 patients

Leon Naar, Ander D. Gallastegi, Raghu R. Seethala, B. Christian Renne,3, Michael E. Billington, Jasmine Kannikal, Haytham M.A. Kaafarani, Jarone Lee,3

1 Division of Trauma, Emergency Surgery & Surgical Critical Care, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston 02114-2696, USA

2 Division of Emergency Critical Care Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital,Harvard Medical School, Boston 02115-6195, USA

3 Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston 02115-6195, USA

Corresponding Author: Jarone Lee, Email: Jarone.Lee@mgh.harvard.edu

July coincides with the beginning of the academic year in teaching hospitals across the United States of America (USA). The increased responsibility assumed by trainees transitioning to a higher role in the healthcare team is hypothesized to lead to poorer patient outcomes,termed the “July Eff ect”.

The consequence of a “July Effect” might be more severe in critical care settings, where the complexity of patients requires a higher level of experience and training. The only studies evaluating the “July Eff ect” in the ICU were published in the early 2000’s.Since that time, several resident work-hour regulations have been implemented by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).These regulations have resulted in more frequent sign-outs, reduced continuity of care, and less clinical time for trainees, which in theory could increase the risk of errors among young trainees at the time they are most vulnerable.

We hypothesized that the implemented changes in duty hours have resulted in a “July Eff ect” in the critical care setting, with worse outcomes for ICU patients admitted in July.

METHODS

Study population

Following IRB approval, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult patients (≥18 years),admitted to ICUs at two major, tertiary care, academic hospitals in Boston from January 2007 to December 2012. The need for informed consent was waived. Data were obtained from surgical ICUs (SICU), medical ICUs(MICU), cardiac care units, burn ICUs, trauma ICUs,cardiac and thoracic surgical ICUs, and neurological ICUs, containing a minimum of 10 beds.

Data collection

Patients were identified from an administrative registry database containing information of all ICU admissions from both hospitals. Demographic information included age, sex, and race. Clinical information included admission and discharge dates,hospital length of stay, type of ICU, and admitting service. Algorithms for the calculation of the Elixhauser comorbidity index (ECI) were generated; ECI is a comorbidity index calculated from 30 different ICD-9 diagnoses.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes were 30- and 365-day mortality rates. In-hospital mortality data were obtained from the electronic medical record. Data for mortality within 365 days from discharge were obtained using the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File.

Sensitivity analyses

We first analyzed only patients admitted in 2012 to assess the impact of 2011 ACGME work-hour update.Second, we analyzed patients admitted to a MICU or SICU separately. Lastly, we compared 30- and 365-day mortality rates between patients admitted in July-August and patients admitted in the remaining months of the year and between patients admitted in July-September and patients admitted in the remaining months of the year.

Statistical analyses

Continuous and categorical variables are presented as median (interquartile range) and frequency (percentage),respectively. Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare characteristics between the groups. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the effect of July admission on 30- and 365-day mortality rates adjusting for gender, race, type of ICU,and ECI. Statistical significance was set at a-value<0.05. All analyses were performed with Stata v15.1(StataCorp 2017; College Station, USA).

RESULTS

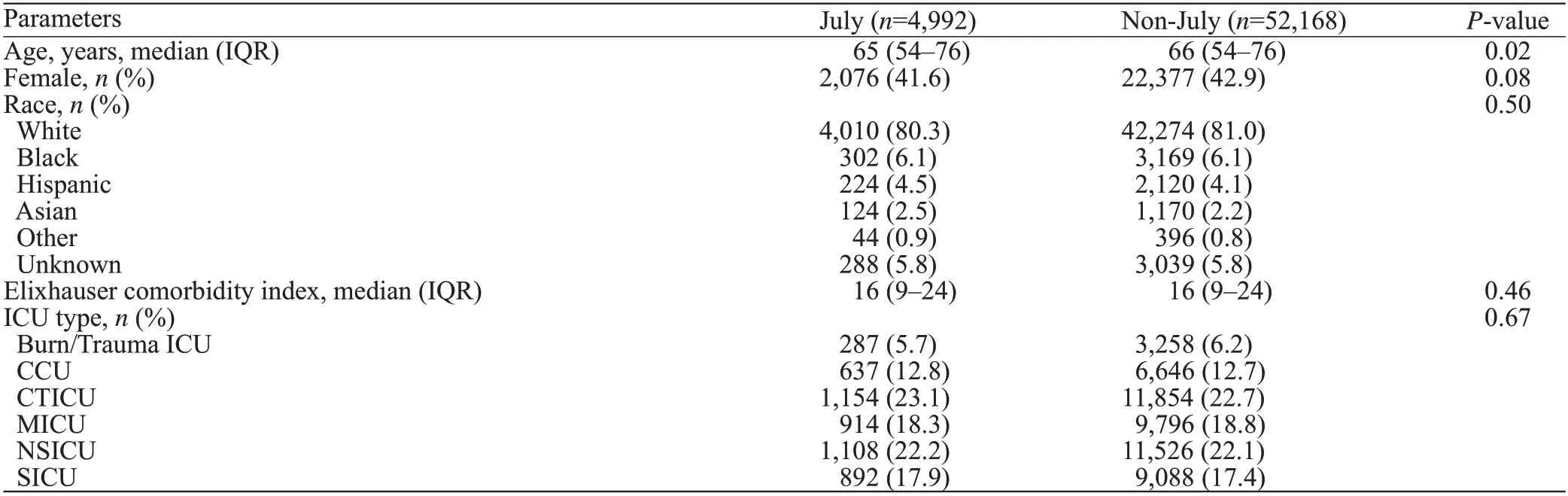

Between 2007 and 2012, 57,160 patients were admitted to an ICU at participating institutions. A total of 4,992 (8.7%) patients were admitted in July, and the age was 65 (54–76) years. Descriptive statistics of patients admitted in July compared with other months are provided in Table 1.

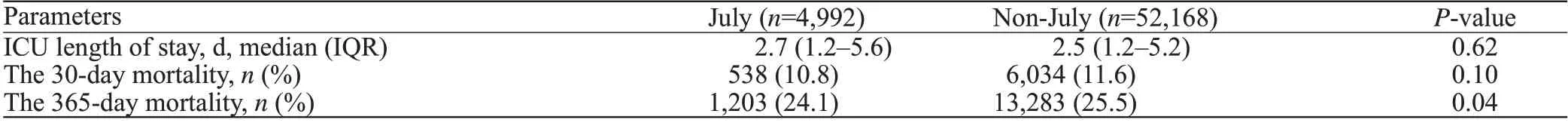

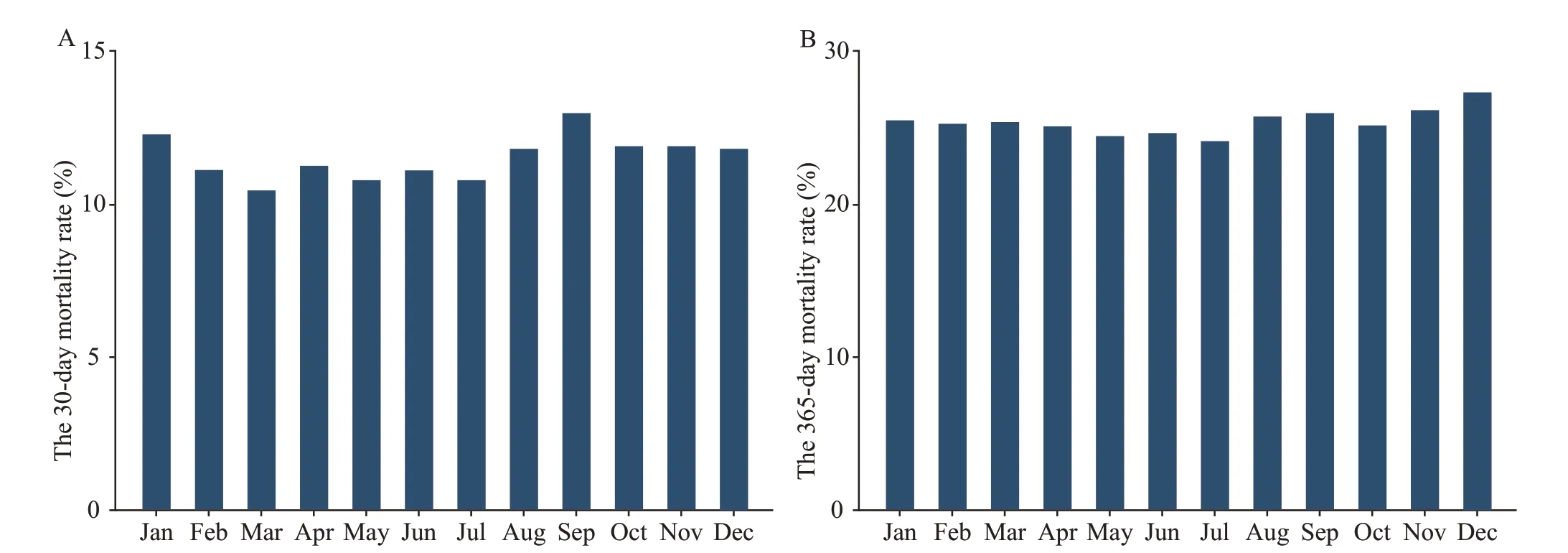

There was no statistical diff erence in the unadjusted 30-day mortality rate for July admissions compared to other months (10.8% vs. 11.6%,=0.10) (Table 2). The unadjusted 365-day mortality rate was signif icantly lower in patients admitted in July (24.1% vs. 25.5%,=0.04). The 30- and 365-day mortality rates for admissions during each month are shown in Figure 1. There were monthly variations in mortality rates that were statistically significant, with September having the highest mortality rate. There was no diff erence in the median duration of ICU length (2.7 d vs. 2.5 d,=0.62).

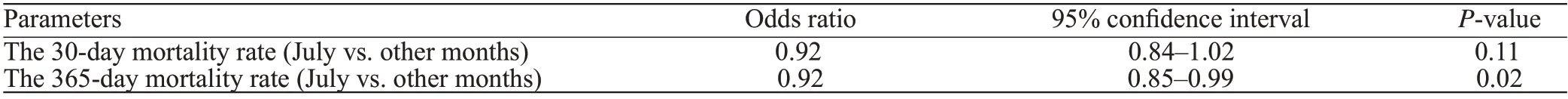

After adjusting for covariates, the admission in July was not associated with the increased 30-day mortality rate compared with the admission in other months (Table 3).However, the July admission was associated with a slightly lower risk-adjusted 365-day mortality rate compared with other months (odds ratio [] 0.92, 95% conf idence interval[95%] 0.85–0.99,=0.02, Table 3).

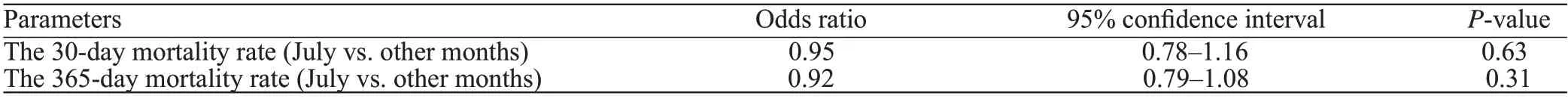

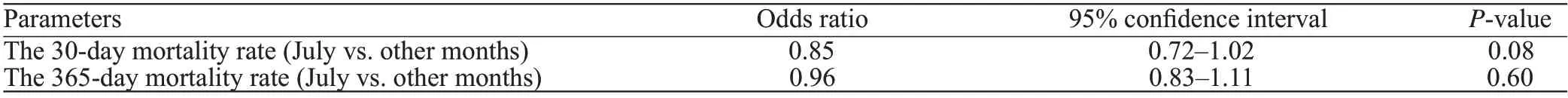

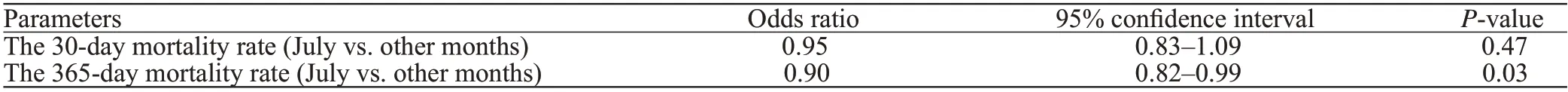

For admissions in 2012, the admission to ICU in July did not result in a worse mortality rate (Table 4). There was no signif icant diff erence in 30- or 365-day mortality rates for patients admitted to the MICU in July compared with other months (Table 5). The admission to a SICU in July was associated with a statistically signif icant risk for the 365-day mortality rate in multivariable analysis (=0.03), but not for the 30-day mortality rate (Table 6).

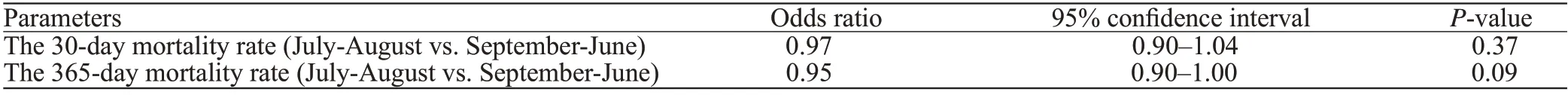

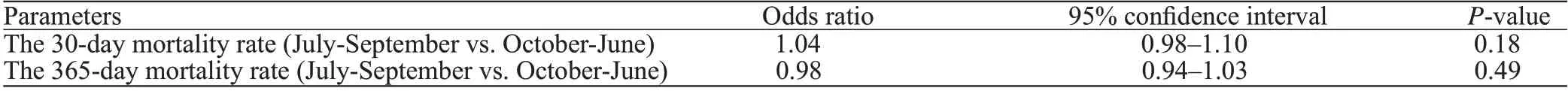

ICU admissions in July-August were not associated with a significant risk of 30- or 365-day mortality rates compared to admissions in September-June (supplementary Figure 1 and Table 7). Similarly, admissions in July-September were not associated with a significant risk of 30- or 365-day mortality rates compared to admissions in October-June (supplementary Figure 2 and Table 8).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients admitted to an intensive care unit in the two institutions over the study period

Table 2. Outcomes of patients admitted to an intensive care unit in the two institutions over the study period

DISCUSSION

In our retrospective cohort study of over 57,000 patients admitted at two tertiary, academic centers, we did not find an increased risk of mortality rate in patients admitted to the ICU in July. We did not find an increased risk of mortality rate in July admissions in separate analyses of only MICU’s and only SICU’s, nor did we f ind a signif icant diff erence in risk-adjusted mortality rate comparing admissions in July-August and July-September with the remaining months of the year.

Our study contributes to the existing literature by evaluating the “July Effect” in ICUs following the implementation of the ACGME work-hour regulations.In 2003, the ACGME established national work-hourstandards to include an 80-hour work week, 1 day off in 7, and a maximum of a 24-hour shift with 6 additional hours if needed for education and/or patient handoff.In 2011,further regulations were added to include a limitation to 16 consecutive duty hours for post-graduate year one trainees and a restriction of senior residents to 24-hour shifts maximum.Our hypothesis was that the increase in handoffs following ACGME regulations at a time in medical training when residents assume new responsibilities would lead to a “July Effect” in the ICU setting. However, such an association was not detected. Potential reasons for this observation are increased trainee supervision, particularly in the ICU setting where 24-hour attending coverage is available,multidisciplinary nature of ICU teams fostering a culture of collaboration and patient safety, compliance with evidence-based protocols and checklists in the ICU, and seasonal variance in illnesses (e.g., inf luenza) that could make mortality diff erences in July seem less signif icant.

Table 3. Results of the multivariable regression analyses for 30-day and 365-day mortality rates in patients admitted to an intensive care unit in July

Table 4. Results of the multivariable regression analyses for 30-day and 365-day mortality rates in patients admitted to an intensive care unit in July (sensitivity analysis including only patients admitted in 2012)

Table 5. Results of the multivariable regression analyses for 30-day and 365-day mortality rates in patients admitted to an intensive care unit in July (sensitivity analyzing patients admitted to the medical intensive care unit)

Table 6. Results of the multivariable regression analyses for 30-day and 365-day mortality rates in patients admitted to an intensive care unit in July (sensitivity analyzing patients admitted to the surgical intensive care unit)

Table 7. Results of the multivariable regression analyses for 30-day and 365-day mortality rates in patients admitted to an intensive care unit in July-August vs. September-June

Table 8. Results of the multivariable regression analyses for 30-day and 365-day mortality rates in patients admitted to an intensive care unit in July-September vs. October-June

Figure 1. The 30-day mortality and 365-day mortality rates per month for patients admitted to an intensive care unit in the two institutions over the study period.

Our study design was similar to prior studiesexamining the “July Effect” in the ICU. One difference is that we used a comorbidity index, ECI, as opposed to a physiologic index such as the Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III to adjust for baseline risk of mortality rate. While prior studies have demonstrated that comorbidity indices from administrative data sets were reasonable predictors of death, our database lacked physiological variables that could more directly represent illness type and severity at the admission.The lack of risk adjustment for physiological variables could have resulted in differences at baseline that were not accounted for. Other limitations of this study included the lack of clinical outcomes other than mortality rates and lack of data regarding the staffi ng model in ICUs.

CONCLUSIONS

In this retrospective study of critically ill patients, we demonstrate that even after implementation of the ACGME work-hour regulations, there is no evidence of a “July Effect” in patients admitted to critical care units at two tertiary, academic institutions in the USA. Despite the ICU mortality rate not being aff ected by the month of July, future studies are needed to evaluate if other processes or adverse events are aff ected by the “July Eff ect”.

None.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at both institutions.

The authors have no commercial associations or sources of support that might pose a conflict of interest.

LN proposed the study and wrote the f irst draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

All the supplementary files in this paper are available at http://wjem.com.cn.

World Journal of Emergency Medicine2022年3期

World Journal of Emergency Medicine2022年3期

- World Journal of Emergency Medicine的其它文章

- Mortality-related electrocardiogram indices in methanol toxicity

- The combination of creatine kinase-myocardial band isoenzyme and point-of-care cardiac troponin/contemporary cardiac troponin for the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction

- Increasing angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2/ACE axes ratio alleviates early pulmonary vascular remodeling in a porcine model of acute pulmonary embolism with cardiac arrest

- Shrinking lung syndrome in autoimmune inflammatory diseases: A case series and review of literature

- Traumatic tension pneumocephalus: A case report

- Blunt myocardial injury and gastrointestinal hemorrhage following Heimlich maneuver: A case report and literature review