Puzzling pacing threshold in a patient with cardiac resynchronization therapy device

Song-yun Chu, Jing Zhou, Yan-sheng Ding

Department of Cardiology, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China

CASE

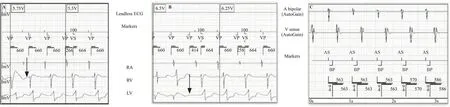

A man in his sixties with dilated cardiomyopathy was admitted to our hospital for the replacement of his cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) device. Although his condition had been initially improved after CRT implantation and he had taken an optimized medication regimen and undergone regular device follow-up, echocardiography showed progressive dyspnea and edema with decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). During the procedure,his CRT was disconnected and tested using an analyzer module 2290 of the Medtronic 2090 programmer (Medtronic Inc., USA), and a temporary pacemaker (Model 5318;Medtronic Inc., USA) and high pacing thresholds (>5 V/0.5 ms) were noted for both ventricles (Figures 1 A and B). No abnormality in sensing or lead impedance was detected. No significant change in the location or integrity of the leads was found by fluoroscopy. Pre-procedure interrogation showed regular ventricular signals in the intracardiac electrogram (EGM) after the pacing spikes throughout the output decreased to their minimum values (Figure 1C).Apparently, excellent thresholds were also shown by EGM after connecting the new device and repeated testing.

Questions

Which is the correct pacing threshold? What is the most likely reason for the discrepancy of the pacing thresholds measured before and during the operation?

A. >5.0 V/0.5 ms, dislodgement of the leads

B. <1.0 V/0.5 ms, malfunction of the analyzer

C. >5.0 V/0.5 ms, inappropriate testing mode selection

Answers

C. >5.0 V/0.5 ms, inappropriate testing mode selection

DISCUSSION

Lack of response to CRT warrants exploration for causes. Because the left ventricular (LV) lead is placed within the coronary sinus rather than in the myocardium,the rates of dislodgement and micro-dislodgement are higher.However, it is diffi cult to explain the increase in right ventricular (RV) thresholds and how they return to normal without any repositioning. Analyzer malfunction is extremely rare,and the measures were conf irmed by the temporary pacemaker testing.

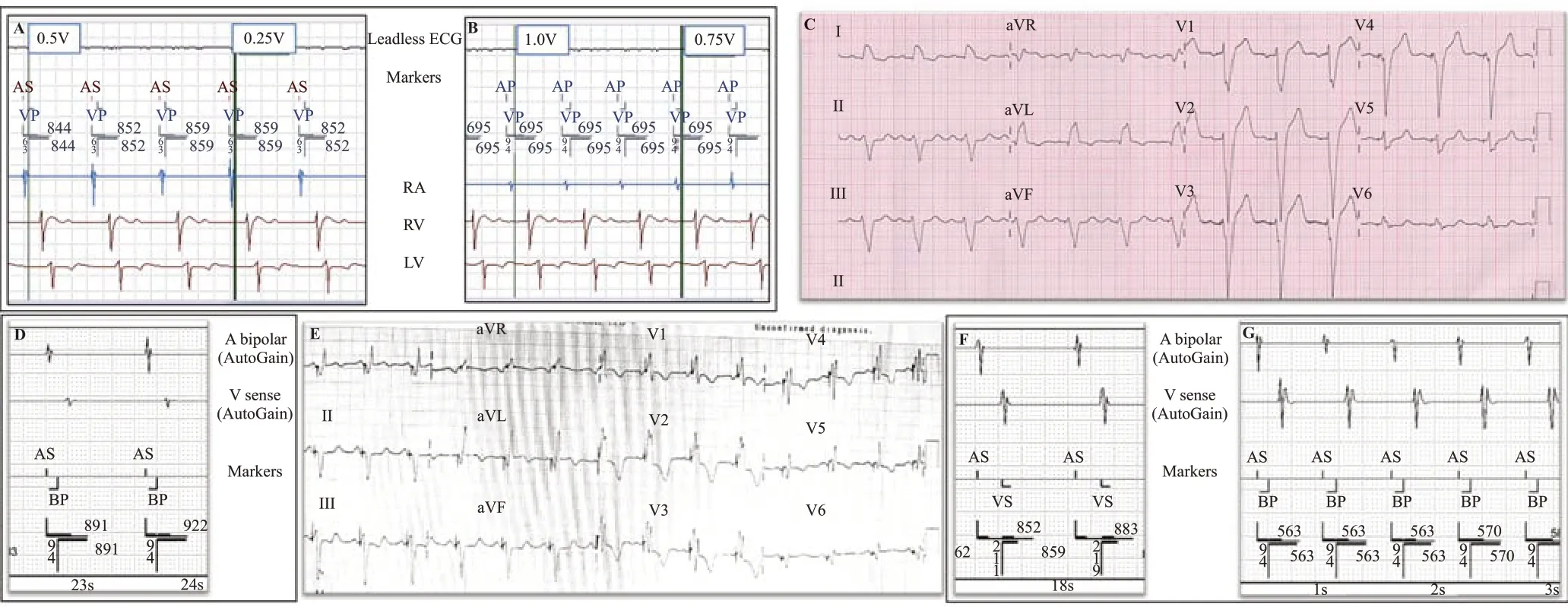

In fact, “satisfactory” thresholds were suggested by regular ventricular signals after the pacing spikes in EGM, while no change in QRS morphology in electrocardiogram (ECG) was noted when modulation of the atrioventricular (AV) and interventricular (VV) delay.Pseudocapture was doubted after testing with DDDmode and short AV delay, in which the atrial signals were sensed and ventricular stimuli were delivered before the intrinsic activation, producing apparently captured beats (Figure 2C). VVI-mode testing, as in the procedure, revealed the dissociation of the stimuli and the ventricular activities. A closer look at the multiple EGMs in DDD-mode showed the long latency between the pacing spikes and the activations. It also showed an intact activation sequence, whichever LV or RV paced(Figures 2 A and B), indicating capture failure. A subtle change occurred in the ventricular EGM (Figures 2 D–G) years earlier and led to the progressive clinical exacerbation.

Figure 1. Pacing threshold testing during the procedure (A and B) and before the procedure (C). A and B: right ventricular and left ventricular pacing threshold test during the procedure; arrows indicated the loss of capture; C: “satisfactory” biventricular pacing before and after the replacement procedure.

Figure 2. Comparison of the EGM and ECG during the procedure and after the initial implantation. A and B: testing of pacing thresholds of right ventricle and left ventricle with DDD-mode and shortened AV delay; C: the pseudocaptured QRS conf iguration was identical to the intrinsic LBBB pattern before the CRT implantation; D and E: EGM and ECG immediately after CRT implantation; F: EGM of intrinsic beats; G: so-called biventricular pacing capture.EGM: electrogram; ECG: electrocardiogram; AV: atrioventricular; LBBB: left bundle branch block; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy.

In viewing the unacceptably high pacing thresholds for RV and LV, we attempted to implant new leads during the procedure. Angiography showed multiple severe stenosis of the left subclavian to supra vena cava. There was also adhesion between the def ibrillation coil and the vessel wall of supra vena cava, which prevented the leads from passing through. After discussing options with the patient, we kept the device acting only as a def ibrillator with minimal ventricular pacing because the patient was not pacemaker-dependent. Elective total extraction of the transvenous ventricular leads and re-implantation of the LV and RV leads under general anesthesia with a cardiac surgeon stand-by were suggested. However, the patient refused further invasive procedure and decided to accept medical treatment for heart failure.

None.

Not needed.

The authors have no commercial associations or sources of support that might pose a conflict of interest.

SYC proposed the study and wrote the f irst draft.All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

World Journal of Emergency Medicine2022年3期

World Journal of Emergency Medicine2022年3期

- World Journal of Emergency Medicine的其它文章

- Mortality-related electrocardiogram indices in methanol toxicity

- The combination of creatine kinase-myocardial band isoenzyme and point-of-care cardiac troponin/contemporary cardiac troponin for the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction

- Increasing angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2/ACE axes ratio alleviates early pulmonary vascular remodeling in a porcine model of acute pulmonary embolism with cardiac arrest

- Shrinking lung syndrome in autoimmune inflammatory diseases: A case series and review of literature

- Traumatic tension pneumocephalus: A case report

- Blunt myocardial injury and gastrointestinal hemorrhage following Heimlich maneuver: A case report and literature review