Application value of biofluid-based biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of spinal cord injury

Hong-Da Wang , Zhi-Jian Wei , Jun-Jin Li Shi-Qing Feng

Abstract Recent studies in patients with spinal cord injuries (SCIs) have confirmed the diagnostic potential of biofluid-based biomarkers, as a topic of increasing interest in relation to SCI diagnosis and treatment. This paper reviews the research progress and application prospects of recently identified SCI-related biomarkers. Many structural proteins,such as glial fibrillary acidic protein, S100-β, ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase-L1,neurofilament light, and tau protein were correlated with the diagnosis, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale, and prognosis of SCI to different degrees.Inflammatory factors, including interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor α,are also good biomarkers for the diagnosis of acute and chronic SCI, while non-coding RNAs (microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs) also show diagnostic potential for SCI. Trace elements (Mg, Se, Cu, Zn) have been shown to be related to motor recovery and can predict motor function after SCI, while humoral markers can reflect the pathophysiological changes after SCI. These factors have the advantages of low cost, convenient sampling,and ease of dynamic tracking, but are also associated with disadvantages, including diverse influencing factors and complex level changes. Although various proteins have been verified as potential biomarkers for SCI, more convincing evidence from large clinical and prospective studies is thus required to identify the most valuable diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for SCI.

Key Words: biomarker; diagnosis; inflammatory cytokine; motor recovery; non-coding RNA; prognosis; spinal cord injury; structural protein; trace element

Introduction

Spinal cord injuries (SCIs) are severe complications of spinal injuries caused by e.g. car accidents and falls, which are accompanied by clinical manifestations including spinal cord concussion and spinal shock (McDonald and Sadowsky,2002; Deng et al., 2020). SCIs cause devastating and longterm disabilities, and improving the prognostication of patients has thus become a long-standing goal in clinical research (Fakhoury, 2015; Eckert and Martin, 2017; Liu et al., 2017). The main clinically proven effective treatment strategies for SCI currently include early decompression,exercise rehabilitation, drug therapy, and cell transplantation(McDonald and Sadowsky, 2002; Guo, 2020; Huang et al.,2020; Sharif and Jazaib Ali, 2020). However, there is still a lack of timely prevention strategies for secondary SCI and of effective treatment measures to achieve satisfactory recovery(Hu et al., 2021).

At present, the presence of typical neurological symptoms combined with spinal cord imaging results are considered as effective and authoritative methods for diagnosing SCI(Mortazavi et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2018). However, the accurate judgement of injury severity and SCI prognosis based on imaging performance and physical examination are limited.Among the available imaging tools, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the most objective and authoritative method for diagnosing SCI, by providing high-resolution and contrast images of the injured spinal cord (Freund et al.,2019). However, early MRI is not always suitable or accessible in patients with unstable SCIs (Wang et al., 2018; Albayar et al., 2019; Seif et al., 2019). Regarding physical examination,although the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury examination is generally considered as the gold standard and is widely applied for the assessment of SCI severity and prognosis (Hales et al., 2015;Chun et al., 2020), this relatively subjective evaluation has certain limitations associated with its time-consuming nature and the need for patient cooperation, which is not applicable to patients in a state of coma, sedation, or spinal shock(Thomas and Murphy, 2018).

The above limitations indicate the urgent need to find other auxiliary indicators to accurately evaluate the degree of injury and clinical prognosis of patients with SCI. Numerous recent studies have revealed that some structural proteins and inflammatory factors in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum can reflect the degree of SCI (Badhiwala et al., 2018).However, although many researchers have reviewed the changes of these biomarkers in SCI, few have focused on which biomarkers are the most beneficial for the diagnosis of SCI, the grading of American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA)Impairment Scale (AIS), and for assessing the prognosis of SCI, which are the most important clinical applications of biomarkers. In this review, we summarize and review recent progress in relation to the common biofluid-based biomarkers with applications in SCI.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

HDW and ZJW performed a literature search of PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar using the following search terms: “spinal cord injury” “biomarkers” “GFAP” “S100β”“NSE” “UCH-L1” “NF” “tau” “MMPs” “IL-6” “IL-8” “TNFα” “IL-1β” “IGF-1” “TGF-β” “non-coding RNAs” “miRNAs” “l(fā)ncRNAs”.Articles focusing on the role of biomarkers in the diagnosis,AIS classification, and motor recovery of SCI were included.Overall, 75 studies published between 2002 and 2021 were included.

Structural Biomarkers for Spinal Cord Injury

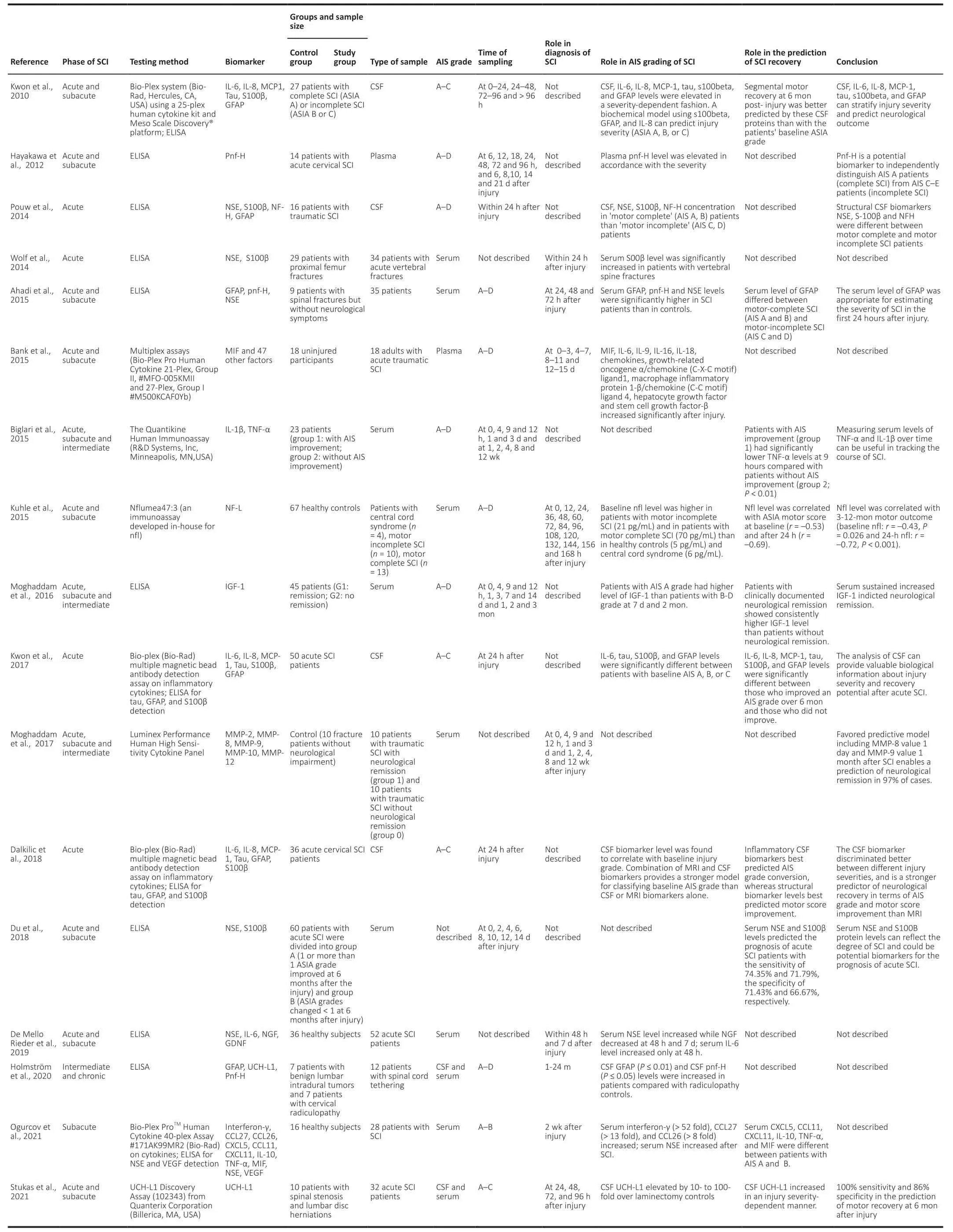

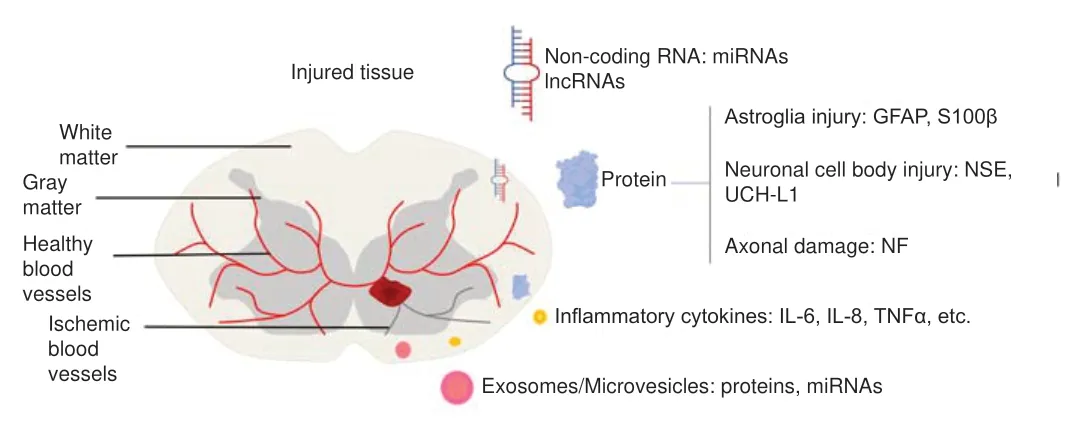

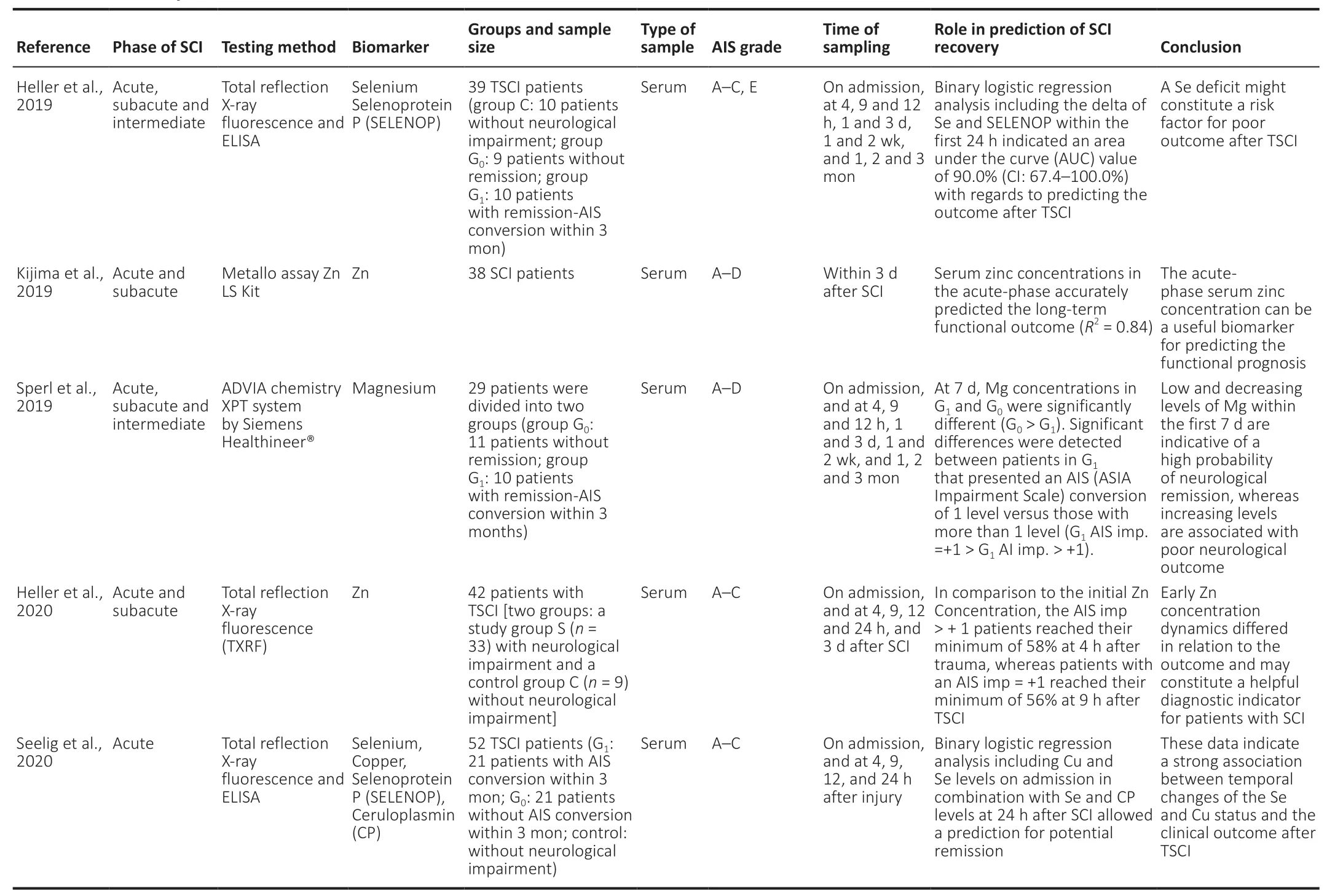

During SCI, neuronal and glial cell damage results in the release of cellular components into the CSF and peripheral circulation through the ruptured blood-spinal cord barrier.The concentrations of these cellular components change over time, making them potentially useful indicators of the severity of SCI and recovery prognosis. Protein biomarkers can conventionally be divided into structural and inflammation-related biomarkers (Kwon et al., 2019). The different pathophysiological processes involved in producing these biomarkers include astroglial injury (S100 calciumbinding protein β, S100β; glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP),neuronal cell-body damage (neuron-specific enolase, NSE;ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1, UCH-L1), axonal damage(neurofilament proteins, NF; myelin basic protein, MBP), and dendritic damage (microtubule-associated protein) (Wang et al., 2018) (Figure 1). Based on the current research results,we divided protein biomarkers into (1) biomarkers related to the diagnosis of SCI, (2) biomarkers related to American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS) classification,and (3) biomarkers related to the prognosis of SCI. We have summarized and discussed the biomarkers in each category,with the aim of identifying two or three biomarkers or their combinations with the greatest clinical potential (Table 1).

Table 1|Summary of structural proteins and inflammatory cytokines in recent human SCI studies published during 2010–2021

Figure 1|Classification of spinal cord injury (SCI) biomarkers.

Astroglial Injury Biomarkers for Spinal Cord Injury

GFAP exists in the astrocyte matrix and is a single-molecule intermediate filament protein with high specificity. It has been confirmed as a robust biomarker of traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Wang et al., 2018) and may also have great value for the assessment of SCI. Kwon et al. (2017) performed CSF GFAP testing and AIS grading in 15 patients with acute SCI at 24 hours and 6 months post-injury. They demonstrated that CSF GFAP concentrations were significantly different among patients diagnosed with AIS grades A, B, and C at 24 hours after SCI injury, and GFAP levels were also significantly different between patients with an improved AIS grade after 6 months of treatment compared with those with no improvement. In their study, GFAP had an 83% probability of predicting neurological improvement in patients with AIS grade A at 6 months after injury, indicating that GFAP might be a useful index for assessing the severity of SCI and for predicting future neurological functional recovery (Κwon et al.,2017). Guéz et al. (2003) showed that GFAP levels were higher in patients with complete motor loss compared with patients with incomplete motor loss. Ahadi et al. (2015) also reported that a higher degree of SCI was associated with higher serum concentrations of GFAP in a study of 35 patients. Obly et al. (2019) recently found that serum GFAP concentrations rose in the first 1–3 days in 31 dogs with simulated SCI, and then gradually decreased and became undetectable by 14 days. Importantly, the serum level of GFAP in the first 3 days predicted recovery with an accuracy of 76.7–86%. Regarding sequelae for patients with chronic SCI, Holmstrom et al. (2020)found that CSF GFAP and phosphorylated neurofilament-heavy(pNF-H) levels were significantly higher in 12 patients with spinal cord tethering compared with radiculopathy controls.Collectively, GFAP has thus been shown to be a strong prognostic biomarker for neurological amelioration after SCI.

S100β is a calcium-binding protein that is mainly present in astrocytes and Schwann cells, and participates in calcium homeostasis, cell proliferation, and differentiation (Donato et al., 2009). Similarly, S100β has been confirmed as a biomarker of TBI and also has an essential role in SCI diagnosis (Hulme et al., 2017). Kwon et al. (2010) detected CSF expression levels of S100β and other cytokines in 27 patients with SCI, and found that combining GFAP with IL-8 and S100β predicted the observed ASIA grade with 89% accuracy at 24 hours and better predicted segmental motor function improvement after 6 months of SCI injury compared with baseline ASIA grade.Similar conclusions were reached in a series of subsequent studies (Wolf et al., 2014). Kwon et al. (2017) verified that CSF S100β levels differed significantly among patients with different AIS grades of SCI at 24 hours post-injury, and S100β was also significantly correlated with improvements in sports scores and the prediction of ASI conversion over 6 months.In a recent study in 60 patients, serum S100β increased after SCI and reached a peak 4 days after injury, and then declined to a relatively low level 2 weeks later (Du et al., 2018). Du et al. (2018) also showed that SCI patients who showed improvements of at least one ASIA grade after 6 months had lower S100β levels than those whose ASIA grade changed by less than one grade throughout the course of the disease.However, despite the diagnostic sensitivity of S100β for SCI, S100β also exists in adipocytes and chondrocytes, and increased serum levels of S100β alone thus lack specificity for diagnosing SCI (Faridaalee and Keyghobadi Khajeh, 2019).

Neuronal Cell Body Injury Biomarkers for Spinal Cord Injury

The glycolytic enzyme NSE is mainly distributed in the cytoplasm of mature neurons and neuroendocrine cells, and is released into the extracellular environment following neuronal axon damage. In an early study of 34 patients with vertebral spine fractures, Wolf et al. (2014) found no difference in serum NSE levels between experimental and normal subjects or among SCI patients classified with paresthesia, incomplete paraplegia, and complete paraplegia. However, Ahadi et al.(2015) subsequently arrived at different conclusions based on significantly higher average serum NSE levels in 35 patients with SCI, compared with the control group at 24 and 48 hours post-injury. Similarly, the results of a study by Pouw et al. (2014) based on 16 patients with acute traumatic SCI showed that CSF levels of NSE were significantly correlated with baseline neurological functions, such as complete motor loss (AIS grade A or B) or incomplete motor loss (AIS C or D).However, recent studies have produced conflicting results: a study of 52 patients by de Mello Rieder et al. (2019) found that serum NSE levels were significantly increased at 48 hours and 7 days after SCI, but found no significant difference between patients with different ASIA grades and no significant correlation between post-injury serum NSE and future neurologic melioration.

However, in a study of 60 patients with acute SCI by Du et al.(2018), serum NSE levels were significantly increased after injury and reached a peak on the 2ndday, and then declined gradually. Furthermore, patients with an improvement of at least one ASIA grade 6 months later had lower serum NSE levels than those who did not recover well (less than one grade improvement). In summary, NSE could serve as a diagnostic biomarker for SCI, and possibly also for severity assessment and prognostic evaluation.

UCH-L1 is a deubiquitinase involved in the addition or removal of ubiquitin in proteins that primarily exists in the cytoplasm of neuronal cells. Yang et al. (2018) showed that CSF and serum UCH-L1 levels peaked rapidly at 4 hours after injury then declined at 24 hours in a rat SCI model. In addition,a recent study of 32 patients with acute SCI revealed that CSF UCH-L1 levels increased dramatically after injury in a severity- and time-dependent way, with 100% sensitivity and 86% specificity for predicting ASIA conversion, despite no differences in serum UCH-L1 levels. Furthermore, a consistent increase in CSF UCH-L1 up to 96 hours and relatively higher CSF levels 24 hours after injury were correlated with a lack of AIS grade improvement and motor function amelioration,respectively (Stukas et al., 2021). An ultrasensitive immunosensor has recently been developed for the rapid detection of UCH-L1 in biofluids in patients with TBI or SCI(Khetani et al., 2019). Overall, CSF levels of UCH-L1 have great potential for the diagnosis of acute SCI, and might qualify as a sensitive biomarker for predicting future neurological recovery.

Axonal Damage Biomarkers for Spinal Cord Injury

NF, as a major component of the axon cytoskeleton, interacts with other cytoskeletal proteins and regulates axonal transportation and neuronal signaling (Yuan et al., 2017). NF exists exclusively in neurons but is released and increased in the extracellular environment following neuronal cell damage,and is thus a potential biomarker for SCI (Al-Chalabi and Miller, 2003). The basic structural components of NF include three polypeptide subunits: neurofilament-light (NF-L, 68K),neurofilament-medium (150K), and neurofilament-heavy(NF-H, 200K), among which phosphorylated NF-H (pNF-H) is most easily detectable in serum and CSF due to its relative resistance to proteases (Shaw et al., 2005). Hayakawa et al.(2012) recruited 14 patients with acute cervical SCI and found that serum pNF-H was detectably increased from 12 hours to 21 days after injury in patients with complete SCI, and there were significant differences in serum pNF-H levels between patients with AIS grade A (completely paralyzed) and AIS grade C (incompletely paralyzed). A later study involving 35 patients also found that serum pNF-H levels were significantly higher in patients with SCI at 24 and 48 hours after injury compared with controls (Ahadi et al., 2015). In addition,serum NF-L has been identified as a potential biomarker in various neurological diseases (Gaetani et al., 2019). In an early clinical study of SCI biomarkers, Guez et al. (2003) examined CSF samples from six patients with acute SCI and found that patients with complete motor loss had higher levels of NF-L than those with partial motor loss, and NF-L levels in the CSF of patients without neurological improvement were 10 times higher than those in patients with improvement, indicating that SCI could be diagnosed based on CSF levels of NF-L. In a subsequent study with a larger sample (23 SCI patients and 67 healthy controls). Κuhle et al. (2015) confirmed that baseline serum NF-L levels were significantly higher in patients with motor-complete SCI (70 pg/mL) and motor-incomplete SCI (21 pg/mL) than in healthy controls (5 pg/mL), and serum NF-L was significantly correlated with ASIA grade and motor score at baseline, 24 hours, and 3–12 months. They also showed that minocycline treatment reduced serum NF-L levels in the subgroup of patients with motor-complete SCI, suggesting that NF-L may help to guide treatment, as well as being a diagnostic and prognostic indicator (Κuhle et al., 2015).

Other Structural Biomarkers for Spinal Cord Injury

Tau, as the most abundant tubule-associated protein,contributes to microtubule formation and stabilization inside neuronal cells. Kwon et al. (2010) showed that CSF tau levels increased in a severity-dependent manner among patients with AIS grades A, B, and C, and that a lower tau level predicted an improvement of one AIS grade at 6 months after SCI injury (Κwon et al., 2017). Dalkilic et al. (2018) confirmed that CSF tau levels differed significantly among SCI patients with AIS grades A, B, and C, and motor score improvement 6 months later was best predicted by structural proteins,such as CSF tau. A recent study demonstrated that CSF and serum tau levels peaked rapidly at 12 hours after injury in a severity-dependent SCI rat model, and Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan locomotor rating scale scores were positively linearly correlated with tau protein levels (Tang et al., 2019).Because tau is hyperphosphorylated under conditions of pathological axonal damage, such as in TBI (Rubenstein et al., 2015), recent studies have examined the potential role of hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) as a biomarker for SCI.Caprelli et al. (2018) proved that the presence of p-tau was in line with the temporal and spatial distribution of axonal damage in SCI model rats, and CSF and serum levels of p-tau were greatly increased after SCI. However, there are currently no clinical data regarding dynamic changes in p-tau in biofluids in SCI patients, and the relationship between p-tau protein and AIS grading remains unknown. Overall,evidence suggests that total tau can serve as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for SCI, while p-tau may also have a certain diagnostic value for SCI.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) comprise a large family of zinc-bound proteases with strong effects on the degradation of protein components in the extracellular matrix.Moghaddam et al. (2017) analyzed the data sets for 115 patients with traumatic SCI (33 women, 82 men) published from 2010 to 2015, including serum MMP levels at different time points from admission to 12 weeks after injury. They found that MMP-8 and MMP-9 levels differed significantly between SCI patients and controls, and the favored predictive model consisting of MMP-8 levels 1 day and MMP-9 levels 1 month after injury could predict neurological remission in 97%of cases (Moghaddam et al., 2017).

Inflammatory Biomarkers for Spinal Cord Injury

Damaged tissues and a ruptured blood-spinal cord barrier following SCI lead to the accumulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the CSF or peripheral blood,enabling these molecules to serve as latent biomarkers.Among the inflammatory mediators, interleukins have been studied extensively in clinical research and have shown great potential as SCI biomarkers. Davies et al. (2007) conducted a cross-sectional study of 56 SCI patients and 35 age-matched controls, and found that serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-1 levels were significantly higher in SCI patients than in controls at 2–52 weeks post-injury; however, increased cytokine levels were not correlated with injury level or AIS classification.However, Bank et al. (2015) found that serum IL-6 levels were significantly elevated in patients with acute SCI, but only in the first week of injury. Similarly, de Mello Rieder et al. (2019)reported that serum IL-6 levels were only increased 48 hours post-injury, and there was no correlation between IL-6 levels and short- or long-term prognosis (i.e., survival rate or sensory and motor function improvement).

CSF levels of interleukins differ from plasma levels in patients with SCI. Kwon et al. (2010) demonstrated that CSF IL-6 and IL-8 increased in severity-dependent manners in SCI patients,and IL-8, together with S100β and GFAP, was used to establish a biochemical model that could predict ASIA grade with 89%accuracy after 24 hours of injury. Furthermore, these CSF proteins were more predictive of segmental motor recovery than baseline ASIA grade at 6 months after injury. Kwon et al. (2017) also verified that CSF IL-6 expression levels differed significantly among patients with acute SCI with baseline ASIA grades of A, B, and C. Moreover, IL-6 was strongly correlated with ASIA conversion and motor improvement 6 months after SCI. In another clinical study comparing CSF and MRI biomarkers for acute SCI. Dalkilic et al. (2018) showed that CSF IL-6 and IL-8 levels were correlated with baseline ASIA grades. In addition,CSF levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, monocyte chemotactic protein-1) performed best for predicting ASIA grade conversion, while structural biomarkers (tau, GFAP, S100β)performed best for predicting motor score improvement.

Other inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and IL-1β, which are secreted mainly by monocytes or macrophages, also participate in the secondary inflammatory response in SCI. Hayes et al. (2002) showed that serum TNFα levels were significantly higher in patients with chronic SCI (>12 months) compared with normal subjects. In addition, Davies et al. (2007) found that higher serum TNFα levels were sustained in SCI patients from 2–52 weeks postinjury, and TNFα levels differed among patients with different ASIA classifications. However, Biglari et al. (2015) found that serum TNFα levels were significantly lower in patients with AIS improvement at 9 hours after SCI than in those without.Meanwhile, serum IL-β levels exhibited a stable decline from 2–12 weeks in SCI patients, despite showing no distinction in relation to ASIA conversion. A recent study by Ogurcov et al.(2021) confirmed that serum TNFα levels differed between patients with ASIA grades A and B. In another study based on 140 participants, Xu et al. (2015) revealed that SCI patients with neuropathic pain had significantly higher serum TNFα levels. In conclusion, serum TNFα could play a part in the diagnosis of SCI, classification of ASIA grade, and prognosis of neurological improvement, and dynamic measurement of serum IL-1 might be useful for tracking the progression of SCI.Other cytokines, such as growth factors, have also proven useful for the assessment of patients with SCI. Ferbert et al.(2017) found that serum levels of insulin-like growth factor 1(IGF-1) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) were both elevated during the acute and sub-acute phases after injury in 23 SCI patients, and higher serum IGF-1 levels predicted insufficient neurological remission 12 weeks later, while TGF-β showed no such effect. However, a study of 45 SCI patients by Moghaddam et al. (2016) drew different conclusions,and found that high serum IGF-1 levels were related to neurological recovery. Information on the relationships between these cytokines and AIS classification is also lacking,and more studies are needed.

Spinal Cord Injury RNA Biomarkers

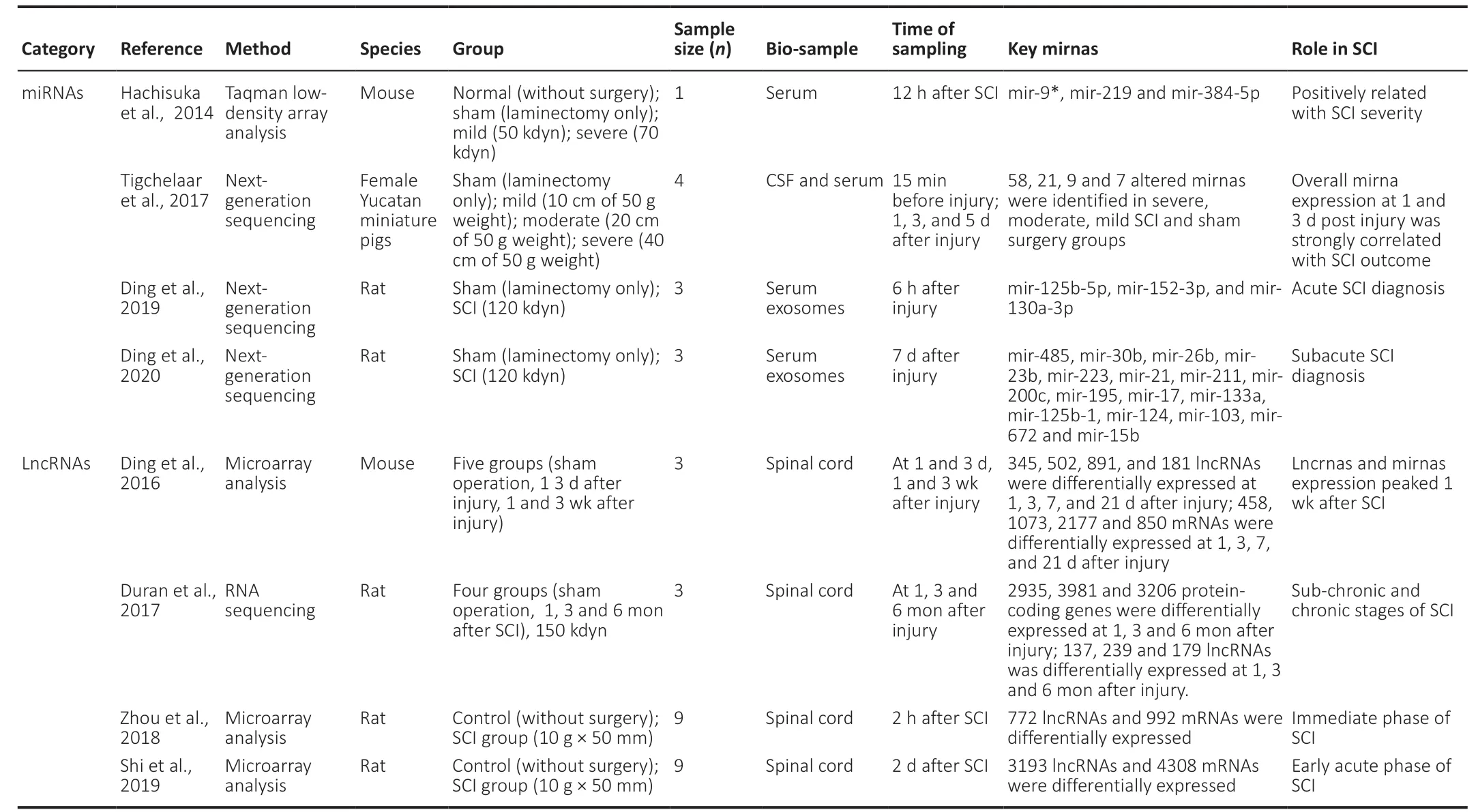

Studies of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) sequences after SCI are shown inTable 2.

Table 2|Non-coding rnas sequencing after SCI

Use of microRNAs as biomarkers for SCI

Single-stranded ncRNA molecules with a length of 22 nucleotides, known as microRNAs (miRNAs), participate in the regulation of post-transcriptional gene expression.Differentially expressed miRNAs have been shown to contribute to pathological reactions (including apoptosis,inflammatory response, angiogenesis, etc.) in SCI, making them potential therapeutic targets for SCI intervention(Nieto-Diaz et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2017). Hachisuka et al.(2014) established a mouse SCI model and found that serum expression levels of miR-9*, miR-219, and miR-384-5p were significantly increased in the normal, sham, mild, and severe groups in a severity-dependent manner at 12 hours after injury. Tigchelaar et al. (2017) evaluated serum miRNA levels at 1, 3, and 5 days after injury in a porcine model of SCI, and quantified seven, nine, 21, and 58 differentially expressed miRNAs in the sham surgery, mild, moderate, and severe injury groups, respectively. They also found that SCI functional outcome was significantly correlated with serum miRNA levels at 1 and 3 days after injury, supporting a role for serum miRNAs as promising biomarkers for the assessment of SCI severity and future functional amelioration.

Although circulating miRNAs have potential as biomarkers in SCI, their concentration and stability in body fluids, such as blood and CSF, are limited. However, exosomes are lipidbilayer-encapsulated particles containing various proteins and miRNAs that are released from cells into the extracellular fluid, and exosomal miRNAs have exhibited greater effects in terms of the pathobiology and therapy of SCI than free miRNAs (Dutta et al., 2021). Ding et al. (2019) analyzed miRNA profiles in serum exosomes at 6 hours after injury in a rat SCI model, and found that serum exosomal miR-125b-5p,miR-152-3p, and miR-130a-3p had sufficient specificity and detectability to act as diagnostic biomarkers for acute SCI.They also confirmed that 141 miRNAs in serum exosomes were differentially expressed between SCI and sham rats at 7 days after injury, showing potential diagnostic and prognostic values for subacute SCI (Ding et al., 2020). Overall, circulating miRNAs, especially exosomal miRNAs, could play a vital role as potential biomarkers for SCI.

Use of long non-coding RNAs as biomarkers for SCI

As a class of ncRNA molecules with more than 200 nucleotides, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are involved in many cellular activities, including epigenetic regulation,the cell cycle, and differentiation regulation. These lncRNAs have been a recent research hot spot, and they have been confirmed to be related to various diseases such as cancer and nervous system diseases (Quan et al., 2017), including SCI(Wang et al., 2019). Studies in rats and mice have revealed a relationship between lncRNAs and SCI (Wang et al., 2019).Ding et al. analyzed the lncRNA profile of the spinal cord in an SCI mouse model and found differential expression of lncRNAs from 1 day after injury, reaching a peak at 1 week and then decreasing until 3 weeks after SCI (Ding et al.,2016). Duan et al. (2017) found that the expression profile of spinal cord lncRNAs changed dynamically during the chronic phase of SCI (1, 3, and 6 months). In another study using SCI rat models, Shi et al. (2019) quantified 3193 differentially expressed lncRNAs and 4308 differentially expressed miRNAs at 2 days after injury, while regarding the immediate phase of SCI, Zhou et al. (2018) identified 772 differentially expressed lncRNAs and 992 differentially expressed miRNAs at 2 hours after injury in a rat model. In a weighted gene co-expression network analysis, Chen et al. (2021) identified six genes(CCNB2, CCNB1, CKS2, COL5A1, KIF20A, and RACGAP1) that could act as potential biomarkers to differentiate among SCI subtypes. However, despite the use of animal models to reveal the specific molecular mechanisms of several lncRNAs in the pathogenesis and progression of SCI (Jiang and Zhang,2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Guan and Wang, 2021), clinical data regarding the potential role of circulating lncRNAs as biomarkers for the diagnosis or prognosis of SCI are extremely limited. The current findings provide a promising basis for future research into the role of lncRNAs in SCI.

Trace Elements as Prognostic Biomarkers for Spinal Cord Injury

Oxidative stress and inflammatory responses are critical factors in the occurrence of secondary injury during the pathological progression of traumatic SCI. Essential trace elements might play a protective role as antioxidants during this process, and may thus have a close relationship with future neurological recovery. Sperl et al. (2019) studied 29 patients with acute traumatic SCI and found that patients without neurological remission (G1) had significantly higher serum Mg levels than patients with neurological remission(G1) within the first 7 days. Heller et al. (2019) and Seeling et al. (2020) found that patients with traumatic SCI with neurological remission (G1) who had a higher serum Se levels on admission exhibited a significantly more rapid decline within the first week compared with patients without neurological improvement, with a similar effect for serum Cu.However, regarding Zn levels, Kijima et al. (2019) reported that a dramatic decrease in serum Zn levels was related to the severity of SCI, and Zn levels 12 hours after injury could predict neurological functional recovery in a mouse model.In addition, they demonstrated that the severity-dependent decrease in serum Zn was due to a proportional increase in Zn uptake by circulating activated monocytes. Heller et al.(2020) also claimed that early changes in serum Zn levels from 0–9 hours after SCI had an accuracy of 82.2% for predicting neurological impairment. In brief, changes in serum levels of essential trace elements may reflect the consistent redistribution of these antioxidants, and temporal fluctuations in these microelements might thus have predictive value in terms of neurological regeneration (Table 3).

Table 3|Summary of trace element in SCI

Limitations

At present, although many potentially effective biomarkers have been discovered, few clinical studies have been conducted to determine which biomarkers are most closely related to the severity and prognosis of SCI, which is a major issue in their clinical application. This review did not consider all the possible biomarkers, and only listed those with the highest correlations with SCI. Regarding the acquisition of repeated CSF samples, careful attention must be paid to aseptic procedures and to ensuring an adequate time interval between samples.

Conclusion

Biomarkers should ideally possess as many of the following properties as possible: (1) changes (preferably increases)in CSF, serum, plasma, or whole-blood levels after SCI, with low levels in normal people; (2) levels in biological fluids easy to measure and quantify using sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays or similar immunoassays, with at least two detection formats or platforms; (3) ability to measure biomarker levels repeatedly within a 48-hour window after SCI; and (4) levels of the biomarker in the biofluid should respond to treatment (Wang et al., 2018).

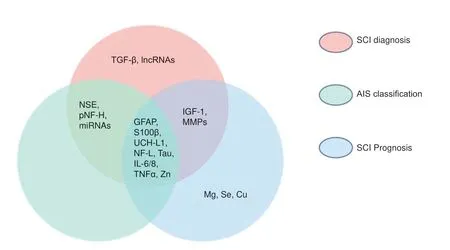

According to the current summary, GFAP, S100β, UCH-L1, NFL, tau, IL-6/8, TNFα, and Zn could be useful diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, and indicators of AIS classification in SCI; NSE, pNF-H, and miRNAs have possible roles in the diagnosis and severity assessment of SCI; IGF-1 and MMPs may be involved in the diagnosis and neurological recovery of SCI; TGF-β and lncRNAs are only useful for the recognition ofSCI; and Mg, Se, and Cu are mainly related to the prognosis of SCI (Figure 2).

Figure 2|Venn diagram of current research results for potential biomarkers of spinal cord injury (SCI).

We assume that the combination of two or three of these recently identified biomarkers may have useful potential in the diagnosis, prognosis, and even treatment of SCI. However,further, high-quality prospective clinical studies are needed to rigorously analyze the sensitivity, specificity, and predictability of the available biomarkers.

Author contributions:Manuscript design: SQF; manuscript writing and revision: HDW and ZJW; table and figure preparation: JJL. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Financial support:This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of Stem Cell and Transformational Research? No. 2019YFA0112100 (to SQF). The funding source had no role in manuscript conception and design? data analysis or interpretation?manuscript writing or deciding to submit this manuscript for publication.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal? and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License? which allows others to remix?tweak? and build upon the work non-commercially? as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewer:Mitsuhiro Enomoto? Tokyo Medical and Dental University? Japan.

Additional file:Open peer review report 1.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- From regenerative strategies to pharmacological approaches: can we fine-tune treatment for Parkinson’s disease?

- Glymphatic imaging and modulation of the optic nerve

- Time-to-enrollment in clinical trials investigating neurological recovery in chronic spinal cord injury:observations from a systematic review and ClinicalTrials.gov database

- Semaphorin7A: its role in the control of serotonergic circuits and functional recovery following spinal cord injury

- Potential neuroprotection by Dendrobium nobile Lindl alkaloid in Alzheimer’s disease models

- Diffusion tensor tractography characteristics of axonal injury in concussion/mild traumatic brain injury