Evidence-based treatment for acute spinal cord injury☆

Zhouming Deng, Jiajia Su, Lin Cai, Ansong Ping, Wei Jin, Renxiong Wei, Yan Zhan

1Orthopedics Center, Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, Hubei Province, China

2Department of Radiology, Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, Hubei Province, China

3Department of Radiation Oncology, Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, Hubei Province, China

INTRODUCTION

Based on data from the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center (NSCISC) for 2010,it is estimated that the annual incidence of spinal cord injury (SCI) in the USA, not including those who die at the scene of an accident, is approximately 40 cases per million head of population. This equates to approximately 12 000 new cases each year[1]. A large number of studies have focused on treatment of SCI[2-4], and advances have been made in both non-operative and operative treatment protocols. This study aimed to formulate therapeutic recommendations for acute SCI, using an evidence-based medicine (EBM) approach for clinical practice.

CLINICAL DATA

A 40-year-old man presented with incomplete tetraplegia following a motor vehicle accident impacting to his head and neck 5 hours earlier. On presentation, he complained of severe pain in his neck with a limited range of motion secondary to the pain, limb weakness, and persistent numbness and tingling in his abdomen and legs.

After simple X-ray, he was transferred to Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University for further treatment.

The patient had a smoking history but no other significant medical history. Physical examination on arrival revealed stable vital signs, with a blood pressure of 130/70 mm Hg,pulse 76 beats/min, tachypnea 32 breaths/min,and clear consciousness.

The patient’s neck was immobilized in a cervical collar. Motor examination revealed bilateral paresis in his lower limbs, with grade 1/5 power in all muscle groups[5]. In the upper limbs, extensor carpi muscle strength was grade 2/5 bilaterally, with elbow flexion muscle strength grade 5/5 on the right but only grade 3/5 on the left. The patient reported abnormal sensation below the level C6dermatomes bilaterally. Reflexes were diminished bilaterally in both the knees and ankles. Hoffman’s and Babinski signs were absent, and there was no clonus.

Rectal sphincter tone and sensation were absent, and the patient was unable to urinate voluntarily; consequently, an indwelling urinary catheter was inserted. The patient’s Barthel ADL index was 15[6]. Sensory and motor functions were evaluated by American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA)function scale[5], with a motor score of 27, a pin-prick score 46, and light-touch score 51.

Laboratory findings were unremarkable. X-ray of the cervical spine showed a compression fracture of the C6vertebral body (supplementary Figure 1 online). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed SCI (C6) (supplementary Figure 2 online), and confirmed the fracture of the C6vertebral body (supplementary Figure 3 online).

The patient was diagnosed as a C6cervical spinal fracture, with incomplete acute SCI (ASIA C).

PROPOSING QUESTIONS

After gaining a thorough understanding of this patient, we proposed questions based on the patient/problem, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) principle of EBM[7]such as: (1) What pharmacologic intervention does this patient need? (2) When should this patient undergo surgery? (3) How to prevent thrombosis in this patient? (4) What should the respiratory management be?(5) Can functional electrical stimulation (FES) promote function recovery for this patient? (6) Is acupuncture efficacious for patients with SCI?

RETRIEVAL EVIDENCE

Data sources

We searched the National Guideline Clearinghouse(NGC; 2000-11), Cochrane library (2011, Issue 1), TRIP Database (2000-11), and PubMed (1966-2011). Pub-Med was searched using the following Medical Subject Heading [MeSH]terms and keywords: "Spinal Cord Injuries/drug therapy" [MeSH]or "Spinal Cord Injuries/mortality" [MeSH]or "Spinal Cord Injuries/prevention and control" [MeSH]or "Spinal Cord Injuries/rehabilitation" [MeSH]or "Spinal Cord Injuries/surgery" [MeSH]or "Spinal Cord Injuries/therapy"[MeSH]or "Spinal Cord Injuries/urine" [MeSH]). The Cochrane Library and NGC and TRIP Database were searched for systematic reviews and clinical guidelines on the theme SCI. The lists of references of retrieved publications were manually checked for additional studies that could potentially meet these inclusions but were not found by the electronic search.

Inclusion criteria

We limited the search to adult humans, and the type of article was limited to systematic review or practice guideline or randomized controlled trial (RCT). Only articles written in English were selected. Reports describing≥ 10 patients were included. Articles concerning other diseases of the spinal cord (such as multiple sclerosis)and chronic SCI were excluded. Results that did not match the inclusion criteria were excluded by reviewing the article title and abstract; the full article for all accepted abstract was then obtained. Based on the review of the full text, the articles were screened again.

Quality assessment of included articles

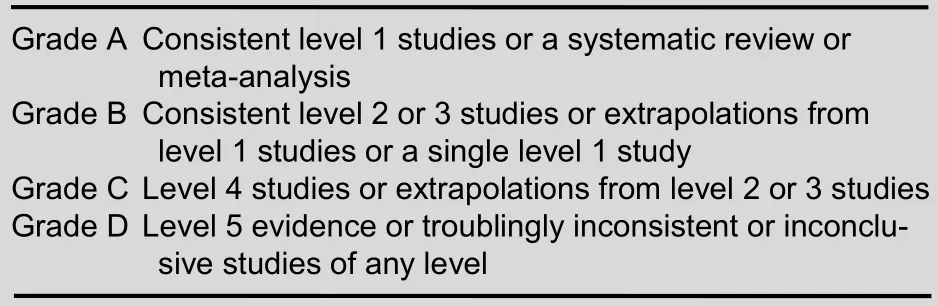

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence[8]. Based on the opinion of Guyatt[9]and the grade previously defined by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine[10], we formulated recommendations for clinical practice and graded these recommendations as shown in Table 1.

Finally, 34 researches (supplementary Table 1 online)were included.

Table 1 Grade of treatment recommendations

RESULTS

What pharmacologic interventions do this patient need?

Drugs frequently used for SCI included methylprednisolone sodium succinate (MPSS), GM1ganglioside (GM1,sygen), and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). The guideline of NGC[11]indicated no clinical evidence exists definitively to recommend the use of any neuroprotective pharmacologic agent, including steroids, in the treatment of acute SCI to improve functional recovery (Level 1 Grade A).

MPSS

The guidelines of NGC[11]recommended that if it has been started, administration of MPSS should be terminated as soon as possible in neurologically normal patients and in those whose prior neurologic symptoms have resolved to reduce deleterious side effects (Level 1 Grade A). This recommendation was also supported by other researches[12-14](Level 1).

NASCIS had conducted three independent trials to test the efficacy of MPSS. The first study found that patients who received high doses of MPSS had no difference in neurological recovery of motor function or pinprick and light touch sensation, but statistically significant increases in complication rates, compared with a standard dose with acute SCI[15-16](Level 1).

The second trial revealed that there was no neurologic advantage with MPSS whereas post hoc comparisons showed that MPSS had neuroprotective effect only when patients received MPSS within 8 hours after injury[17-18](Level 1 Grade A). The third trial concluded that for patients undergoing MP therapy initiated within 3 hours of injury, 24-hour maintenance is appropriate,while patients starting therapy 3-8 hours after injury should be maintained on the regimen for 48 hours unless there are complicating medical factors[19-20](Level 1 Grade A), supported by two systematic reviews (Level 1)of Bracken[21-22].

GM1

GM1is one kind of sialic acid-containing glycosphingolipids distributed in all tissues but occurring in the highest concentration in CNS. Geisler et al[23]conducted an RCT of GM1in 34 patients with spinal cord injuries, with a follow-up period of 1 year after injury to assess recovery.

GM1significantly improved ASIA motors ≤ 48 hours after injury (Level 2 Grade B). Further to determine efficacy and safety of Sygen (GM1), Geisler et al[24]conducted an RCT of two doses of Sygen versus placebo, and found that Sygen improved ASIA motor, light touch, and pinprick scores, bowel function, bladder function, sacral sensation, and anal contraction (Level 2 Grade B). A systematic review implemented by Chinnock et al[25]offered another conclusion: there were more deaths in the treatment group compared with the control group(Level 1 Grade A).

TRH

Pitts et al[26]organized a randomized, double blind, controlled, clinical trial of a small sample (20 patients). Four months after TRH treatment, significant improvements were seen in neurologic and sensory function for patients with incomplete SCI. TRH treatment seemed associated with significantly higher motor, sensory, and Sunnybrook scores than placebo (Level 2 Grade B). Larger multicenter clinical trials of TRH are needed to confirm the efficacy of TRH.

Brief summary

Based on these evidences, we believe that controversies exist about the efficacy of pharmacologic interventions in patients with acute SCI. Therefore, clinicians should consider the possibility to increase complication rate when applying drugs.

What is the optimal time for this patient to undergo surgery?

The definition of early surgery although not fixed is generally considered < 24 hours.

The guidelines of NGC[11]recommended that early surgical spinal canal decompression in the setting of a deteriorating SCI would be a practice option that may improve neurologic recovery. Fehlings et al[27]concluded that early decompression (within 24 hours) should be considered as part of the therapeutic management of any patient with SCI, particularly those with cervical SCI. Very early decompression (within 12 hours) should be considered for a patient with an incomplete cervical SCI (with the possible exception of central cord syndrome) (Level 1 Grade A). Another systematic review concluded that early surgical stabilization leads to shorter hospital stays,shorter intensive care unit (ICU) stays, less days on mechanical ventilation, and lower pulmonary complications[28]. Some evidence indicates that early stabilization does not increase complication rates compared with late surgery (Level 1 Grade A), consistent with the results of two systematic reviews[29-30].

How to prevent thrombosis?

The guideline of NGC[11]recommended that mechanical compression devices early after injury and low- molecular weight heparin injection or unfractionated heparin plus intermittent pneumatic compression can prevent phlebothrombosis in all patients when primary hemostasis becomes evident (Level 1 Grade A). Ploumis et al[31]concluded that: (1) The presence of SCI in patients with spinal trauma was associated with more episodes of deep vein thrombosis than was the case for patients without SCI and requires thromboprophylaxis(Level 3, Grade B); and (2) Low-molecular-weight heparin is more efficacious than unfractionated heparin for prevention of deep vein thrombosis in patients with acute SCI (Level 1, Grade A). Furlan et al[32]found that there was insufficient evidence to support (or refute) a recommendation for routine screening for deep vein thrombosis in adults with acute traumatic SCI under thromboprophylaxis (Level 1, Grade A). Gorman et al[33]found that the presence of prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filters in acute SCI patients may paradoxically increase the risk of deep vein thrombosis, which has its own associated morbidities and costs (Level 2,Grade B).

What is respiratory management for this patient?

The guideline of NGC[11]recommended that clinicians should monitor patients closely for respiratory failure in the first day following SCI, and admit patients with complete tetraplegia and injury level at C5 or rostral to an ICU (Level 2, Grade B). Besides, it would be better for doctors to treat retained secretions due to expiratory muscle weakness with manually assisted coughing ("quad coughing"), pulmonary hygiene,mechanical insufflation-exsufflation, or similar expiratory aids in addition to suctioning (Level 4,Grade C). A systematic review reflected that treatments aiming at improving ventilation, cough, and secretion clearance reduced atelectasis, pneumonia,and need for mechanical ventilation[34](Level 1, Grade A). Another systematic review concluded that RMT tended to improve expiratory muscle strength, vital capacity, and residual volume[35](Level 1, Grade A). However, two systematic reviews found that there were insufficient data strongly to support the use of exercise training, or RMT for improving respiratory function in people with SCI[36-37](Level 1). The RCT carried out by Pillastrini et al[38]proposed that the use of mechanical insufflation/exsufflation is an efficacious adjunct to manual respiratory kinesitherapy because it enables adequate broncho-pulmonary clearance, even removing thick, deep secretions (Level 2, Grade B).

Can functional electrical stimulation (FES) promote functional recovery of this patient?

FES has been widely employed as a rehabilitation therapy or as an exercise regimen for the paralyzed lower limbs of individuals with SCI. A systematic review implemented by Hamzaid et al[39]concluded that FES-evoked leg exercise promoted certain health and fitness benefits for patients with SCI (Level 1, Grade A).

Another systematic review concluded that FES training altered skeletal muscle size and morphology, enhanced metabolism including aerobic fitness and functional exercise capacity, and improved psychosocial outlook accompanied by positive changes in bone mineral density and stiffness[40]. Another study also affirmed the benefits of FES[41](Level 2). Whereas, a systematic review carried out by Glinsky et al[42]revealed modest beneficial effect of FES in patients with stroke. It remains unclear whether patients with other types of neurological disabilities (such as SCI) can benefit from FES in the same way (Level 1).

Is acupuncture efficacious for patients with SCI?

Acupuncture is a characteristic treatment of traditional Chinese medicine, which is also one of modalities for functional recovery for patients with SCI. Shin et al[43]launched a systematic review based on seven RCTs performed in China, and found favorable effects of acupuncture on functional recovery and urinary function.

Moreover, pooled analysis of two trials that assessed bladder dysfunction showed good efficacy compared with conventional treatment (Level 1, Grade A). Another systematic review found that acupuncture in acute SCI may significantly improve long-term neurologic recovery and help with management of chronic pain associated with these injuries[44](Level 1, Grade A).

Therapeutic evaluation

The patient was discharged from hospital 6 weeks postoperatively, and returned for an outpatient clinic visit 3 months after surgery. He complained of sexual dysfunction, and the intrinsic muscles of his hands were almost paralyzed. However, he was able to urinate and defecate without difficulty, and could walk with the assistance of a crutch. His Barthel ADL index was 50. Motor examination showed grade 3/5 power in all muscle groups of the left lower limb and grade 4/5 power in all muscle groups of the right lower limb. Muscle tone,power, and reflexes were normal in both upper limbs.

There was persistent numbness in his abdomen. ASIA function scale to evaluate sensory and motor function revealed a motor score of 78, pin-prick score 89, and light-touch score 86. The patient was ASIA D according to ASIA classification. X-ray of the cervical vertebra showed stable internal fixation with no screw loosening(supplementary Figure 4 online).

APPLICATION OF EVIDENCE AND THERAPEUTIC EVALUATION

Application of evidence

I. We informed the patient to stop smoking, and did not administer any neuroprotective pharmaceuticals.

II. We performed an anterior cervical operation 6 hours after trauma.

III. The patient was admitted to ICU for 2 days postoperatively, and monitored closely for respiratory failure with a tracheotomy instrument set reserved at the bedside. Routine antibiotics (ceftriaxone) were administered for 7 days.

IV. The patient received low-molecular weight heparin(enoxaparin; Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France) 40 mg hypodermic injection once daily starting from 3 days postoperatively for 14 days. Intermittent pneumatic compression of the lower extremities was applied throughout the whole period from admission to discharge.

V. The patient was turned over every 2 hours, and encouraged to cough and expectorate; this latter effort was assisted with back percussion and suction on occasion.

VI. The patient was trained to conduct respiratory muscle training for ≥ 15 minutes twice daily for 5-7 days/week for 8 weeks.

VII. The patient was transferred to the rehabilitation department 14 days postoperatively, where he received FES for 15 minutes and acupuncture for 30 minutes daily.

CONCLUSION

We present a case of acute SCI treated using an evidence-based protocol and obtained good results.

Tremendous controversies persist about the efficacy of pharmacologic intervention for patients with acute SCI, but if there are no operative contraindications surgical stabilization is recommended as soon as possible for SCI patients. Low-molecular weight heparin is efficacious for the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with acute SCI, and RMT tends to improve respiratory function. In addition, FES and acupuncture can promote their functional recovery.

Author contributions:Zhouming Deng and Lin Cai were in charge of the study design and wrote the manuscript. Jiajia Su,Ansong Ping, Wei Jin, Yan Zhan, and Renxiong Wei participated in the search of evidence.

Conflicts of interest:None declared.

Ethical approval:This study received permission from the Ethics Committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, China.

Supplementary information:Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, by visiting www.nrronline.org, and entering Vol. 6, No. 23, 2011 item after selecting the “NRR Current Issue” button on the page.

[1]NSCISC. Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance, updated 2011.[2011-01-12]. Available from: URL: https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/public_content/pdf/Facts%202011%20Feb%20Final.pdf

[2]Mei XF, Liu C, Lv G, et al. Can muscle-derived stem cells serve as seed cells to repair spinal cord injury? Neural Regen Res. 2010;5(19):1451-1455.

[3]Sayenko DG, Alekhina MI, Masani K, et al. Positive effect of balance training with visual feedback on standing balance abilities in people with incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2010;48(12):886-893.

[4]Jiao JJ, Jiang JN, Du B, et al. Extract of ginkgo biloba EGb761 inhibits cell apoptosis following spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2010;5(22):1745-1749.

[5]American Spinal Injury Association. International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (revised) Chicago,IL: American Spinal Injury Association. 2006.

[6]Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md Med J. 1965;14:61-65.

[7]Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, et al. The well built clinical question: a key to evidence based decisions. ACP J Club.1995;123:A12-13.

[8]OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group*. "The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence". Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

[9]Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-926.

[10]OCEBM. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine - Levels of Evidence (March 2009) [2011-1-12]. Available from: URL:http://www.cebm.net/indexaspx?o=1025.

[11]Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Early acute management in adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31(4):403-479.

[12]Hurlbert.RJ. Methylprednisolone for acute spinal cord injury: an inappropriate standard of care. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(1 Suppl):1-7.

[13]Short DJ, El Masry WS, Jones PW. High dose methylprednisolone in the management of acute spinal cord injury-a systematic review from a clinical perspective. Spine Cord. 2000;38(5):273-286.

[14]Hugenholtz H, Cass DE, Dvorak MF, et al. High-dose methylprednisolone for acute closed spinal cord injury--only a treatment option. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29(3):227-235.

[15]Bracken MB, Collins WF, Freeman DF, et al. Efficacy of methylprednisolone in acute spinal cord injury. JAMA. 1984;251(1):45-52.

[16]Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Hellenbrand KG, et al.Methylprednisolone and neurological function 1 year after spinal cord injury. Results of the national acute spinal cord injury study. J Neurosurg. 1985;63(5):704-713.

[17]Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, et al. A randomized,controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(20):1405-1411.

[18]Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, et al. Methylprednisolone or naloxone treatment after acute spinal cord injury: 1-year follow-up data. Results of the second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. J Neurosurg. 1992;76(1):23-31.

[19]Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, et al. Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the Third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Randomized Controlled Trial. National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. JAMA. 1997;277(20):1597-1604.

[20]Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, et al. Methylprednisolone or tirilazad mesylate administration after acute spinal cord injury:1-year follow up. Results of the third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(5):699-706.

[21]Bracken MB. Pharmacological interventions for acute spinal cord injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001046.

[22]Bracken MB. Methylprednisolone and acute spinal cord injury: an update of the randomized evidence. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(24 Suppl):S47-S54.

[23]Geisler FH, Dorsey FC, Coleman WP. Recovery of motor function after spinal-cord injury-a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with GM-1 ganglioside. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(26):1829-1838.

[24]Geisler FH, Coleman WP, Grieco G, et al. The Sygen multicenter acute spinal cord injury study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(24 Suppl):S87-S98.

[25]Chinnock P, Roberts I. Gangliosides for acute spinal cord injury.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;18(2):CD004444.

[26]Pitts LH, Ross A, Chase GA, et al. Treatment with thyrotropinreleasing hormone (TRH) in patients with traumatic spinal cord injuries. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12(3):235-243.

[27]Fehlings MG, Rabin D, Sears W, et al. Current practice in the timing of surgical intervention in spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(21 Suppl):S166-S173.

[28]Dimar JR, Carreon LY, Riina J, et al. Early versus late stabilization of the spine in the polytrauma patient. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).2010;35(21 Suppl):S187-S192.

[29]Carreon LY, Dimar JR. Early versus late stabilization of spine injuries: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). In press.

[30]La Rosa G, Conti A, Cardali S, et al. Does early decompression improve neurological outcome of spinal cord injured patients?Appraisal of the literature using a meta-analytical approach.Spinal Cord. 2004;42(9):503-512.

[31]Ploumis A, Ponnappan RK, Maltenfort MG, et al.Thromboprophylaxis in patients with acute spinal injuries: an evidence-based analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(11):2568-2576.

[32]Furlan JC, Fehlings MG. Role of screening tests for deep venous thrombosis in asymptomatic adults with acute spinal cord injury:an evidence-based analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(17):1908-1916.

[33]Gorman PH, Qadri SF, Rao-Patel A. Prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement may increase the relative risk of deep venous thrombosis after acute spinal cord injury. J Trauma. 2009;66(3):707-712.

[34]McCrory DC, Samsa GP, Hamilton BB, et al. Treatment of pulmonary disease following cervical spinal cord injury. Evid Rep Technol Ass. 2001(27):1-4.

[35]Van Houtte S, Vanlandewijck Y, Gosselink R. Respiratory muscle training in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review.Respir Med. 2006;100(11):1886-1895.

[36]Brooks D, O'Brien K, Geddes EL, et al. Is inspiratory muscle training effective for individuals with cervical spinal cord injury? A qualitative systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(3):237-246.

[37]Sheel AW, Reid WD, Townson AF, et al. Effects of exercise training and inspiratory muscle training in spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31(5):500-508.

[38]Pillastrini P, Bordini S, Bazzocchi G, et al. Study of the effectiveness of bronchial clearance in subjects with upper spinal cord injuries: examination of a rehabilitation programme involving mechanical insufflation and exsufflation. Spinal Cord. 2006;44(10):614-616.

[39]Hamzaid NA, Davis GM. Health and fitness benefits of functional electrical stimulation-evoked leg exercise for spinal cord-injured individuals: a position review. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2009;14(4):88-121.

[40]Davis GM, Hamzaid NA, Fornusek C. Cardiorespiratory,metabolic, and biomechanical responses during functional electrical stimulation leg exercise: health and fitness benefits. Artif Organs. 2008;32(8):625-629.

[41]Postans NJ, Hasler JP, Granat MH, et al. Functional electric stimulation to augment partial weight-bearing supported treadmill training for patients with acute incomplete spinal cord injury: A pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):604-610.

[42]Glinsky J, Harvey L, Van Es P. Efficacy of electrical stimulation to increase muscle strength in people with neurological conditions: a systematic review. Physiother Res Int. 2007;12(3):175-194.

[43]Shin BC, Lee MS, Kong JC, et al. Acupuncture for spinal cord injury survivors in Chinese literature: a systematic review.Complement Ther Med. 2009;17(5-6):316-327.

[44]Dorsher PT, McIntosh PM. Acupuncture's effects in treating the sequelae of acute and chronic spinal cord injuries: a review of allopathic and traditional chinese medicine literature. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. In press.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- NIH funding for disease categories related to neurodegenerative diseases

- A case of thalamic hemorrhage-induced diaschisis☆

- Occlusion of the middle cerebral artery Guidance by screen imaging using an EDA-H portable medium-soft electronic endoscope☆

- Propofol regulates Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ balance in the spinal cord after ischemia/reperfusion injury***★

- Using Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry to analyze differentially expressed brain polypeptides in scrapie strain 22L-infected BALB/c mice***☆

- Optimal velocity encoding during measurement of cerebral blood flow volume using phase-contrast magnetic resonance angiography*☆