Management of splenic artery aneurysm associated with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction

New Delhi, India

Management of splenic artery aneurysm associated with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction

Pramod Kumar Mishra, Sundeep Singh Saluja, Ashok K Sharma and Premanand Pattnaik

New Delhi, India

BACKGROUND: Splenic artery aneurysms although rare are clinically significant in view of their propensity for spontaneous rupture and life-threatening bleeding. While portal hypertension is an important etiological factor, the majority of reported cases are secondary to cirrhosis of the liver. We report three cases of splenic artery aneurysms associated with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and discuss their management.

METHODS: The records of three patients of splenic artery aneurysm associated with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction managed from 2003 to 2010 were reviewed retrospectively. The clinical presentation, surgical treatment and outcome were analyzed.

RESULTS: The aneurysm was >3 cm in all patients. The clinical symptoms were secondary to extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (hematemesis in two, portal biliopathy in two) while the aneurysm was asymptomatic. Doppler ultrasound demonstrated aneurysms in all patients. A proximal splenorenal shunt was performed in two patients with excision of the aneurysm in one patient and ligation of the aneurysm in another one. The third patient had the splenic vein replaced by collaterals and hence underwent splenectomy with aneurysmectomy. All patients had an uneventful post-operative course.

CONCLUSIONS: Splenic artery aneurysms are associated with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Although technically difficult, it can be safely performed in an experienced center with minimal morbidity and good outcome.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2012;11:330-333)

splenic artery aneurysm; extrahepatic portal vein obstruction; portal hypertension; proximal splenorenal shunt

Introduction

Splenic artery aneurysm (SAA) is the third most common abdominal aneurysm after those of the aorta and iliac artery and comprises the majority of visceral artery aneurysms.[1]Pregnancy and portal hypertension are the most common risk factors for the development of SAA.[2]Hemodynamic change resulting from portal hypertension is implicated in the pathogenesis of SAA and liver cirrhosis is the underlying cause of portal hypertension in the majority of reported cases.[3,4]Here, we report our experience with three cases of SAA in association with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction managed surgically and discuss the presentation and surgical options for these patients.

Case reports

Case 1

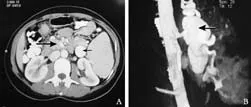

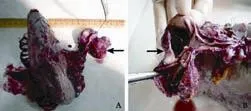

A 27-year-old female presented with left upper abdominal pain for 2 months. She had multiple episodes of hematemesis requiring blood transfusions for the last 10 years. Bleeding was not associated with jaundice, fever or encephalopathy. She had mild pallor with moderate splenomegaly. Blood examination showed low total leukocyte (3.03×109/L) and platelet counts (90×109/L). Doppler ultrasound revealed normal liver echotexture, portal vein cavernoma and an SAA measuring 5×5 cm with multiple intra-abdominal collaterals. A contrastenhanced CT scan of the abdomen confirmed the findings of portal hypertension with a bilobed SAA (Fig. 1). Endoscopy revealed isolated gastric varices type I. She underwent ligation and excision of the SAA witha proximal splenorenal shunt. Perioperative findings indicated a 5×5 cm bilobed SAA involving the middle half of the splenic artery with splenomegaly (Figs. 2 and 3) and multiple perisplenic and peripancreatic collaterals. The operative time was 390 minutes and blood loss 300 mL. She had an uneventful post-operative course and histopathology confirmed a true aneurysm. A 4-year follow-up shows that the patient is doing well.

Case 2

Fig. 1. A: Axial section contrast-enhanced CT showing an aneurysm (thin arrow) with multiple collaterals (thick arrow); B: Coronal section showing a bilobed aneurysm (arrow) arising from the splenic artery.

Fig. 2. Intra-operative photograph showing the ligated splenic artery with a bilobed aneurysm (arrow) in case 1.

Fig. 3. A: Resected specimen of the spleen with a bilobed aneurysm (arrow); B: A section of the artery showing an aneurysmal sac (arrow).

A 35-year-old female presented with multiple episodes of hematemesis requiring hospital admissions and blood transfusions in 3 years. She also had jaundice associated with cholestatic features. Clinical examination revealed pallor and icterus with massive splenomegaly. Hematological parameters suggested the presence of hypersplenism with anemia (hemoglobin, 6 mg%), leukopenia (1.2×109/L) and thrombocytopenia (67×109/L). Liver function tests revealed conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Doppler ultrasound revealed normal liver echotexture with bilateral intra-hepatic biliary radical dilatation, portal vein cavernoma, and a 5×4 cm SAA with multiple intra-abdominal collaterals. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed bilateral intra-hepatic biliary radical dilatation with hilar block secondary to extrinsic compression suggestive of portal biliopathy with a fusiform SAA of 5×4 cm. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed grade III esophageal varices with mild portal hypertensive gastropathic changes. She underwent laparotomy and the intra-operative findings included a large fusiform aneurysm of the splenic artery (5×4 cm) with multiple collaterals. The splenic vein was replaced by multiple collaterals, hence the patient underwent splenectomy with devascularization and aneurysmectomy. The operative time was 300 minutes and blood loss 300 mL. The postoperative course was uneventful and she was discharged after 5 days. At 1-year follow-up she is doing well.

Case 3

A 35-year-old female complained of fever, jaundice and abdominal pain for 1 week. Clinical examination revealed pallor, icterus with moderate splenomegaly. Blood examination revealed leukopenia (2.3×109/L) and thrombocytopenia (68×109/L). Liver function tests revealed conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with raised alkaline phosphatase. Doppler ultrasound showed dilated biliary radicles, portal vein cavernoma and multiple SAAs. She underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and biliary stenting followed by stent exchange for recurrent cholangitis after one month. Meanwhile, she was subjected to shunt surgery with ligation of the aneurysms. Peri-operative findings revealed moderate splenomegaly with 3 large aneurysms of the splenic artery with multiple perisplenic and peripancreatic collaterals with large collaterals in the hepatoduodenal ligament. She underwent a proximal splenorenal shunt with the ligation of SAAs. The operative time was 390 minutes and blood loss was 500 mL. She was discharged on postoperative day 5 with an uneventful course. At 6-month follow-up, the shunt was patent and she underwent cholecystectomy associated with choledochoduodenostomy.

Discussion

SAA is a rare clinical entity. It is common in multiparous females since there is a predilection for the splenic artery to respond to the changes of pregnancy, including hormonal effects and blood flow changes. SAAs are known for their propensity for spontaneous rupture especially in pregnancy and carry the highest morbidity among all visceral artery aneurysms.[5]

Risk factors and diseases associated with SAA include atherosclerosis, autoimmune conditions (e.g., lupus, vasculitides), collagen vascular diseases, pregnancy and portal hypertension.[2]Up to 24% of patients with SAA have portal hypertension, while the reported incidence of SAA in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension varies from 7% to 20%.[6]In portal hypertension, there exists a "splenic hyperkinetic state" that promotes the development of SAA. Among portal hypertensive patients, those with SAA have significantly increased splenic venous flow, splenic artery diameter, and portosystemic shunts. The formation of large portosystemic shunts is thought to reduce resistance and increase flow through the splenic vein; consequently, an increase in splenic artery blood flow is required to increase portal pressure and maintain liver perfusion resulting in the formation of aneurysms.[3]Pathological examination of aneurysms reveals the presence of arterial fibrodysplasia (medial layer degeneration) which is a consequence of hemodynamic changes in the splenic artery resulting in the formation of aneurysms.[2]

The majority of patients with SAA are asymptomatic as in our series, while left abdominal pain or discomfort is the most common symptom in symptomatic patients. CT scan and Doppler ultrasound are commonly used investigative modalities for the diagnosis of SAA. They provide information regarding the size and location of the aneurysm, but they are not very sensitive in diagnosing small, leaking aneurysms.[7]Angiography is the gold standard to localize the lesion and determine the presence of multiple aneurysms.[8]

Therapy is indicated for patients with SAA including symptomatic aneurysms and asymptomatic aneurysms of>2×2 cm. However in patients with portal hypertension, therapy is indicated irrespective of size since there is a high incidence of spontaneous rupture in these patients. All three patients had aneurysms of >2×2 cm and associated portal hypertension. Treatment options can be classified into endovascular and open/laparoscopic therapy. Endovascular treatment options are coil/glue embolization and stent exclusion. Surgical options are bipolar ligation, aneurysmectomy and excision of the aneurysm with splenectomy depending upon the location of aneurysm.[9,10]Treatment options in patients with portal hypertension depend upon its etiology. Qiu et al[11]reported surgical management for giant SAAs associated with portal hypertension with a good outcome. Two patients had underlying cirrhosis while one had aneurysm with portal fistula. Other reports suggest endovascular treatment as an alternative in high-risk patients such as those with cirrhosis.[12,13]In the literature, the majority of patients with portal hypertension complicated with SAA have cirrhosis as the underlying etiology and only limited information is available on the management of extrahepatic portal vein obstruction with SAA.[14]

The management in these patients is different from that in cirrhotics as they are good risk surgical candidates. Surgery is a one-time treatment option and simultaneously treats both problems. In patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and SAA, the treatment option depends upon the presence of bleeding esophagogastric varices or portal biliopathy. Endovascular therapy can be an option in a subgroup of patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction without bleeding or jaundice. Surgical treatment is indicated to treat symptomatic extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and aneurysm simultaneously. Excision of the aneurysm is the preferred option while ligation can be done in the case of multiple aneurysms. In our series, case 1 had bleeding varices and hence underwent a proximal splenorenal shunt and excision of the aneurysm, which was therapeutic for both the SAA and the underlying extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. In case 2, the splenic vein was replaced by multiple collaterals hence a shunt could not be performed and only aneurysmectomy and splenectomy were carried out and the patient underwent endoscopic therapy for portal biliopathy. In case 3, in view of the multiple aneurysms only splenic artery ligation without excision was done along with a proximal splenorenal shunt. Our cases demonstrate that surgery in the form of shunt or splenectomy with devascularization along with excision or ligation of the aneurysm can be performed with minimal morbidity in this subgroup of patients with a good success rate.

In conclusion, SAAs are associated with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Though technically difficult, it can be safely performed in an experienced center with minimal morbidity and good outcome.

Contributors: MPK and SSS proposed the report. SSS and PP wrote the first draft. MPK and PP performed the surgery. SAK analyzed the imaging and provided input. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. SSS is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Competing interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Sheps SG, Spittel JA jr, Fairbairn JF 2nd, Edwards JE. Aneurysms of the splenic artery with special reference to bland aneurysms. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1958;33:381-390.

2 Stanley JC, Fry WJ. Pathogenesis and clinical significance of splenic artery aneurysms. Surgery 1974;76:898-909.

3 Ohta M, Hashizume M, Ueno K, Tanoue K, Sugimachi K, Hasuo K. Hemodynamic study of splenic artery aneurysm in portal hypertension. Hepatogastroenterology 1994;41:181-184.

4 Liu CF, Kung CT, Liu BM, Ng SH, Huang CC, Ko SF. Splenic artery aneurysms encountered in the ED: 10 years' experience. Am J Emerg Med 2007;25:430-436.

5 Gerald B, Zelenock MD, James C. Splanchnic artery aneurysms. In: Robert B, Rutherfurd MD, eds. Vascular Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, Co;2000:1370-1373.

6 Boijsen E, Efsing HO. Aneurysm of the splenic artery. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1969;8:29-41.

7 Mattar SG, Lumsden AB. The management of splenic artery aneurysms: experience with 23 cases. Am J Surg 1995;169:580-584.

8 Parmentier JM, Liesenborghs L, Van Ruyssevelt C. Multiple aneurysms of the splenic artery. J Belge Radiol 1998;81:244.

9 McDermott VG, Shlansky-Goldberg R, Cope C. Endovascular management of splenic artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1994;17:179-184.

10 de Perrot M, Bühler L, Deléaval J, Borisch B, Mentha G, Morel P. Management of true aneurysms of the splenic artery. Am J Surg 1998;175:466-468.

11 Qiu JF, Xu L, Wu ZY. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of giant splenic artery aneurysms with portal hypertension: report of 4 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2004;3:526-529.

12 Briard RJ, Lee J, Doyle T, Thompson P. Endovascular repair of a portal hypertension-related splenic artery aneurysm using a self-expanding stent-graft. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2009; 32:1111-1113.

13 Roland J, Brody F, Venbrux A. Endovascular management of a splenic artery aneurysm. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2007;17:459-461.

14 Debnath J, George RA, Rao PP, Ghosh K. Splenic artery aneurysm--a rare cause for extrahepatic portal venous obstruction: a case report. Int J Surg 2007;5:351-352.

April 21, 2011

Accepted after revision September 26, 2011

Author Affiliations: Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery (Mishra PK, Saluja SS and Pattnaik P), and Department of Radiology (Sharma AK), GB Pant Hospital, New Delhi, India

Sundeep Singh Saluja, MCh, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, GB Pant Hospital and Maulana Azad Medical College, 1, Jawaharlal Nehru Marg, New Delhi 110002, India (Tel: 91-971-859-9259; Email: sundeepsaluja@yahoo.co.in)

? 2012, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(12)60170-2

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2012年3期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2012年3期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Pancreas-preserving segmental duodenectomy for gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum and splenectomy for splenic angiosarcoma

- Induction, modulation and potential targets of miR-210 in pancreatic cancer cells

- Quantitative analysis of intestinal gas in patients with acute pancreatitis

- Can the biliary enhancement of Gd-EOB-DTPA predict the degree of liver function?

- Quality control measures for lowering the seroconversion rate of hemodialysis patients with hepatitis B or C virus

- Effect of recombinant human growth hormone and interferon gamma on hepatic collagen synthesis and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells in cirrhotic rats