Acceptability of Bush Meat as a Source of Animal Protein in Delta State, Nigeria: Implication for Extension Services

Ebewore S O, Ovharhe O J, and Emaziye P O

Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Delta State University, Asaba Campus, Delta State, Nigeria

Acceptability of Bush Meat as a Source of Animal Protein in Delta State, Nigeria: Implication for Extension Services

Ebewore S O, Ovharhe O J, and Emaziye P O

Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Delta State University, Asaba Campus, Delta State, Nigeria

The study examined the acceptability of bush meat to Deltans. The specific objectives were to ascertain the consumption pattern of bush meat; identify the major types of bush meat consumed in the area; determine the likely constraints to bush meat consumption; and stipulate the extension implication of the findings. A systematic sampling technique was used to compose a sample size of 410 respondents. Data used for this study were collected using well structured interview schedule and data were analyzed using descriptive statistical techniques such as tables, percentages, means and standard deviation, and inferential statistics (linear regression model). The result of the study indicated that almost all the respondents (402) representing about 98% was formally consuming bush meat. The findings also revealed that as many as 323 individuals, representing 78.8% of the respondents did not consume bush meat currently. Only about 12.7% and 8.5% occasionally and regularly consumed bush meat respectively. It was therefore very obvious that people no longer consumed bush meat in Delta state as before. The results further indicated that the predominant bush meat consumed in the area were cane rat (97.70%) and the African giant snails (Achatina and Archachatina) (94.25%). The result of the multiple regression analyses indicated that the coefficient for education (X3), income (X5), Ebola (X6) and availability of game (X7) were significant at 5%, indicating that these variables were important factors influencing the consumption of bush meat in the study area. However, the coefficients of education level and Ebola factor were negative and significant, suggesting respondents with higher education and aware of Ebola disease were not likely to consume bush meat. As the result, it was concluded that bush meat was now almost unacceptable due to several factors like dread of Ebola disease, unavailability of game, educational level and income, which significantly affected the consumption of bush meat. It was therefore recommended among others that extension delivery services on how to domesticate game species should be available to farmers.

game, acceptability, Ebola, extension, Cane rat, Delta, Nigeria

Introduction

Animal protein is usually regarded as being superior to plant protein as it usually contains most of the essential amino acids. Because food from animal, especially bush meat or game, are good sources of highly bio-available micronutrients, the nutritional value of bush meat is widely acknowledged (Murphy and Allen, 2003); in many rural settings, bush meat is the primary source of the animal protein consumed (Fa et al., 2003; Nasi et al., 2008). Malaisse and Parent (1982) reported that more proteins are derived from bush meat than from domestic animals (sheep, pigs). It has always been suggested that one of the ways to alleviate the general protein shortage in Africa would be to resort to a greater use of game as a human food resource (Skinner, 1967, 1973; Crawford, 1968, 1974; Topps, 1975). This is especially so in places like Delta State, Nigeria where livestock production is limiteddue to tsetse fly and other environmental hazards. Studies from Madagascar have indicated that lacking of access to game would result in a 29% increase in the number of children with anaemia (Golden et al., 2011). Available evidence indicates that fresh bush meat compares favourably well with domestic meat in yield of lean meat per kg of live weight (mineral and protein content) (Asibey and Eyeson, 1973), superior fat content (Hoogesteijn, 1979) and caloric (energy) value (Hladik, 1987). It is therefore not surprising that Ajayi (1977) recommended the domestication of rodents as sources of protein. Unfortunately, protein from animal sources especially wild animals is beyond the reach of most people since it might be quite expensive. To obtain protein from animal sources easily, communities living near forests in Nigeria commonly obtain their animal proteins from bush meat or game.

Bush meat is a term in Africa which refers to the meat of wildlife. The term bush meat, also known as wild meat or game meat, refers to meat from nondomesticated or wild mammals, reptiles, amphibians and birds or insects hunted for food in jungles/forests (Nasi et al., 2008). These animals are captured or killed by indigenous people for income and subsistence (Cowlishaw et al., 2005).

The volume of the bush meat trade in West and Central Africa was estimated at 1-5 million tonnes per year at the turn of the last century (Bush meat Crisis Task Force, 2015). According to the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in 2014, about 5 million tonnes were still being eaten per year in the Congo Basin (Hogenboom, 2014). For the people of this region, bush meat represents a primary source of animal protein in their menu, making it a significant commercial industry. According to a study in Gabon in 1994, annual sales were estimated at US$50 million. The study found that bush meat represented over half of meat sold in local markets, with primates accounting for 20% of the total game traded (CBS News, 2014). Endangered species, including lemurs from Madagascar that are facing extinction are killed for bush meat despite this being illegal. Roughly 75% of the population consume game meat regularly in Ghana, 70% in Liberia and 60% in Botswana (FAO, 1989). In Sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of wild animal meat consumed as protein is exceptionally high. The major factor influencing wild animal consumption seems to be the adequacy of supply.

Game hunting is encouraged by high prices of wild animals, which have led hunters to maintain supply from ever-decreasing wildlife populations. Studies on hunting and bush meat trade have been conducted in several West and Central African countries but not many in Nigeria (Ape Aliance, 1998). In Nigeria, there is also dearth of studies relating to bush meat consumption pattern. In Delta State, there is no detailed studies on the consumption of bush meat, and the factors dictating the consumption of bush meat, especially in the light of the recent Ebola crisis, have not been ascertained.

Bush meat is a cardinal source of animal protein in both rural and urban families throughout Africa. The level of exploitation and consumption, however, varies from country to country and is determined primarily by its availability, governmental regulations on exploitation, socio-economic status and cultural restrictions. In areas where wild animals still exist, people collect, hunt or purchase and eat game meat for several reasons. The fact is that in Africa most rural people regard bush meat as a vital dietary item for a complex combination of reasons dictated by lacking of alternate sources: financial limitations, preference and cultural values. For these people, bush meat is regarded as a valuable food resource which cannot be easily substituted for without causing wide-ranging socio-economic imbalances. In west Africa, where exploitation of wild animals and their products is well documented (Asibey, 1978; Ajayi, 1979; Sale, 1981; Martin, 1983; Ntiamoa-Baidu, 1987), bush meat is consumed by all the classes of people and is preferred to domestic meat. In southern Africa, the Bushmen do not keep any domestic stocks and rely predominantly on wild animals for their proteins (Maliehe, 1993).Most of the meat eaten in Botswana is from game, although the proportion of wild to domestic meat in people's diets varies within the country. For instance, all the meat eaten by the hunting and gathering groups is bush meat, whereas the cattle-ranching, tribesmen may get about 80% of their meat from wild animals and the remainder from domestic animals (Butynski and von Richter, 1972; Prescott-Allen and Prescott-Allen, 1982). In Tanzania, people living close to forests and grasslands are provided with food security in the form of cheap bush meat (Chihongo, 1992) and in all regions of Malawi, wild animal food, such as insect larvae, honey, termites and meat of large mammals are exploited for food (Nyirenda, 1993).

A lot of work was done in the 1970s and early 1980s to document bush meat consumption, particularly in West Africa, but not so much in Nigeria (Ape Aliance, 1998). In Delta state, there is no detailed study on the consumption of bush meat, and the factors dictating the consumption of bush meat have not been ascertained. There is therefore the need to carry out a study on the consumption of bush meat in this state. The data on consumption of bush meat in Nigeria; however, were mostly based on estimates and moreover little attention was placed on the factors likely to affect bush meat consumption. Some of the earlier studies in Nigeria gave annual wild animal consumption figures ranging from 20% of the animal protein among rural people living in Nigeria's rain forest areas as compared with 13% in the whole country, to 75% in rural Ghana compared to 9.2% nationally, 70%-80% in Cameroon's forest zone compared with 2.8% for the entire country and as much as 80%-90% in Liberia (Ajayi, 1979; Asibey, 1977). The criteria for these estimates raise some doubts and some authors have attributed the high figures to "over-enthusiastic advocacy of the value of bush meat". Some more current statistics are available on bush meat consumption in individual households and communities in some places within Africa (Keita, 1993). Bush meat consumption in C?te d'Ivoire was estimated at 83 000 tons in 1990 (Feer, 1993) and in Liberia, which was estimated that 75% of the country's meat sources came from bush meat, with subsistence hunting accounting for as much as 105 000 tons of meat annually (Anstey, 1991). Statistics on meat consumption in Cameroon in 1981 was 33.1 kg per person per year or 9 g per day, of which bush meat accounted for 8.8%, with 34.1% coming from fish and the rest from domestic sources. The proportion contributed by bush meat represented 28 500 tons of bush meat per year (Gartlan, 1987). Among village communities, Infield (1988) estimated bush meat consumption of 100 kg per person per year in communities around the Korup National Park (Cameroon) as compared to a consumption of 250 g per adult per week in a Ghanaian village, Akyem Ayirebi (Dei, 1991). These estimates are centred on the limited records reported to Wildlife Departments or on food consumption surveys, such as those reported by FAO. The limitation of such data is that they neither capture the actual volume of bush meat exploited nor cover the entire range of species taken. Species such as rodents, snails and insects, which are often consumed by the hunter and his family, hardly appear in the markets and therefore do not appear in the statistics. Furthermore, the figures for bush meat consumption do not reflect the actual situation that prevails in many rural African communities. There is therefore the need for more studies in this area.

Studies on meat consumption indicates that bush meat is still popular, with over 90% of people interviewed preferring bush meat to meat from domestic animals (Falconer, 1992; Ntiamoa-Baidu, 1992; Tutu et al., 1996). In Liberia, popular wild species consumed as bush meat included antelopes and various species of monkeys (Jeffrey, 1977; Verschuren, 1983). In Nigeria, bush meat is popular among both urban and rural dwellers and provides 20% of animal protein in southern Nigeria. The most commonly consumed species are small mammals, such as squirrels, cane rats, West African giant rats, duikers, brush-tailed porcupines and bats (Ajayi, 1979; Martin, 1983; 1984; Anadu, 1987). An estimated total of 1 320 000 metric tonnes of bush meat was huntedby farmers in three ecological zones, within 6 month period (Adeola and Decker, 1987). In Senegal, bush meat exploitation was estimated at 373 600 metric tonnes per year (Cremoux, 1963). Bush meat was once a staple food in many Sierra Leonean's diets. Despite the serious scarcity of wildlife throughout the country, bush meat sale is common in most rural and urban markets and about 55% of all the households consume bush meat on a regular basis (Smith, 1979; Teleki and Balduin, 1981). In Central Africa Republic, for the Aka Pygmies, bush meat is not only the major source of protein, but also provides income and means of exchange for carbohydrate food items. In Gabon, bush meat is sold or consumed depending on the size, personal and public appeal. Small game and rodents are usually eaten locally white porcupines, duikers, lizards and crocodiles are mainly sold on the bush meat markets (Lahm, 1993). In Tanzania, bush meat is a major source of cheap protein for both rural and urban populations and is of great importance particularly for people living around parks and reserves (Chihongo, 1992). In Zaire, huntergatherers living in the forest areas obtain practically all their animal proteins from the forest and up to 200 animal species ranging from large and medium sized mammals, to birds, reptiles and insects are exploited for food (Ichikawa, 1993). In Southern Africa and Botswana, most of the animal proteins come from wild animals of every kind and size, including not only what is traditionally considered as game but meat of all the mammals including predators, birds and their eggs, bats and insects (Richter, 1970; Butynski and von Richter, 1972). In all the regions of Malawi, wild animals are exploited for food (Nyirenda, 1993). In South Africa, for rural communities living very close to forests, natural woodlands and fallow areas, wild animals usually play a significant place in local diets. Exploiting large wild animals is legally forbidden, but various species including rock hyrax, porcupines, bush pigs and hares are hunted for food. Reptiles and amphibians are relished as delicacies (Maliehe, 1993). In Zimbabwe, in addition to large mammals which are hunted illegally, rodents and birds are extensively exploited in all small scale farming areas. Honey and insects are exploited and consumed by almost all households (McGregor, 1991; Wilson, 1990). An attempt to estimate bush meat exploitation over a wider area was made by Adeola and Decker (1987) who conducted a survey on utilisation of bush meat by farmers and hunters in three ecological regions (rain forest, deciduous forest and Savannah) in Nigeria. Bushbucks and duikers were found to be the main large mammal species harvested in all three ecological regions. Small mammals formed the bulk of animals exploited. Of the small mammals, three rodents, the grasscutter (cane rat), giant rat and squirrels were the most abundant. The study estimated that a total of 1 264 000 metric tons of bush meat, comprising small and large mammals but excluding elephants, were exploited by the farmers per month during the rainy season. This was made up of 696 000 metric tons from the savannah region, 183 000 tons from the deciduous forest region and 385 000 tons from the rain forest region. Despite lacking of precise estimates on bush meat consumption and total production, the fact remains that bush meat is one of the most valued and preferred animal protein items in both rural and urban diets in many parts of Africa. Studies in Ghana (e.g., Falconer, 1990, 1992; Ntiamoa-Baidu, 1992) showed that over 90% of the people interviewed in both urban and rural areas would eat bush meat if it was available and for approximately 40%-70% of the people, bush meat was the preferred meat. The popularity of bush meat was confirmed by the results of a survey of the meat preference of customers visiting chop bars (traditional restaurants) in Accra, where they had a choice of various types of meat and fish dishes (Tutu et al., 1993); 65% of the 374 visitors to the chop bars selected bush meat dishes. Unlike areas in central Africa where bush meat is still relatively abundant and accounts for the greater proportion of household animal protein consumption, the actual contribution to total protein intake in west Africa is presently very low. The current low contribution of bush meat to theprotein intake in the region was attributed to scarcity, relatively high prices and the unavailability in small affordable pieces, particularly in the rural areas' since most of the hunters catch were sold as whole animals to be retailed in city markets. Thus, whereas in the past bush meat was the most common source of animal protein, it is currently a luxury item, eaten only occasionally in most homes, and for those who relish bush meat but cannot afford the cost of purchasing it for use in their homes, the chop bars remain their main source of bush meat dishes.

In spite of these developments, studies on the exploitation and consumption of Bushmen, especially on the role of bush meat in animal protein consumption are rare in Delta State, Nigeria. It therefore becomes imperative that study on the level of consumption of bush meat be carried out in Delta State.

Recently the Ebola virus, for which the primary host is suspected to be fruit bats, has been traced to bush meat. Between the first documented outbreak in 1976 and the largest in 2014, the virus had transferred from animals to humans only 30 times, despite large numbers of bats being killed and sold each year. In Ghana, for instance, 100 000 bats are sold annually, yet not a single case of transmission has been reported in the country. Primates may carry the disease, having contracted the disease from bat droppings or fruit touched by the bats. Like humans, it is often fatal for the primate (Hogenboom, 2014). Although primates and other species may be intermediates, evidence suggests people primarily get the virus from bats. Since most people buy pre-cooked bush meat, hunters and people preparing the food have the highest risk of infection. Hunters usually shoot, net, scavenge or catapult their prey, and studies indicate that most hunters handle live bats, come in contact with their blood, and often get bitten or scratched (Hogenboom, 2014). In 2014, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa originated in south-eastern Guinea and was linked to bush meat after it was learned that the first case came from a family that hunted two species of fruit bat, (Hogenboom, 2014) (Hypsignathus monstrosus and Epomops franqueti). In western Africa, bush meat is an old tradition, linked with proper nutrition. Because livestock production is minimal, people often consume bush meat in a way comparable to how European societies consume rabbit or deer meat. Media coverage of the 2014 Ebola outbreak and its link to bush meat has been criticized because it has failed to focus on the primary risk of infection, which is person-to-person. (Hogenboom, 2014). This has seriously affected the consumption of bush meat in most parts of Nigeria. For instance, bush meat sellers in Watt Market in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria, lamented the poor sales of bush meat since the outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Nigeria in July 2014. During a recent survey in the market, only nine bush meat carcasses were observed for sale by three resident traders (two brushtailed porcupines, two red duikers, two blue duikers and one piece of red river hog). In 2009, a visitor to the same market would have been able to find at least 20 carcasses of seven species on sale (Bassey et al., 2010). The traders berated the current media campaign in Nigeria which has warned people against the consumption of wild animals (bush meat) as a possible source of the dreaded Ebola virus disease. Many people have since heeded this advice and are avoiding bush meat altogether. Demand for this once highly esteemed delicacy had been high prior to the Ebola outbreak in Nigeria and threatened the very existence of certain rare and endangered species. One of the traders interviewed complained that business has been very bad since the Ebola outbreak in July, 2014 and lamented that it can now take up to one week for her to sell a piece of bush meat. Prior to Ebola outbreak she was routinely selling 10 to 20 pieces in a single day! Though trading and consumption of bush meat is not banned in Calabar, not fewer than four states in Nigeria have since banned the harvesting and sale of bush meat in an attempt to prevent the spread of Ebola-Ondo, Kano, Rivers and Kogi States. The federal government of Nigeria in its effort to contain the spread of Ebola has also banned the importation of bush meat from other west African countries. At thecommunity level, some communities have also enacted local bans on the harvesting, trading and consumption of bush meat amidst the fear surrounding Ebola. For instance, Buanchor and Kakwagom communities surrounding Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuary in Nigeria have banned the harvesting and sale of bush meat with severe punitive measures taken against anyone found violating the directives. Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuary is one of three sites in Nigeria where Cross River gorillas are found, and also contains the Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee. Consequently, patronage for bush meat has drastically dropped, so that some dealers in the commodity have diverted to other forms of business while consumers now instead patronize meat from domestic animals and fish for their protein needs. Thankfully the Ebola outbreak in Nigeria looks to have been successfully contained. Once the fear surrounding Ebola has abated it may be that the demand for bush meat will soon return to normal. In the meantime, we hope that a long-lasting reduction in the sale and consumption of bush meat, especially in communities surrounding protected areas, will help relieve hunting pressure on Nigeria's rare and endangered species. On the other hand, however, this will adversely affect the economy of families that depend on the bush meat business for survival. The emerging issues now are: Has the consumption of bush meat equally dropped in Delta State, Nigeria? Does Ebola problem pose a threat to bush meat consumption or could there be other factors likely to affect bush meat consumption in Delta state? Accordingly, this study aimed to ascertain the consumption pattern of bush meat; identify the major types of bush meat consumed in the area; determine the likely constraints to bush meat consumption; and critically look at the extension implication of the findings. The study tested the following null hypothesis: there was no significant relationship between some factors and bush meat consumption.

Research Methodology

The study was undertaken in Delta State, Nigeria, located in West Africa. Delta state was created from the defunct Bendel state on August 27, 1991 by the regime of General Ibrahim Babangida. The State covers a total area of about 18 050 km2of which over 60% is land. The State lays approximately between Longitude 5°00 and 6°.45' East and Latitude 5°00 and 6°.30' North. It is bounded in the north and west by Edo State, in the East by Anambra, Imo, and Rivers States, South-East by Bayelsa State, and on the Southern flank is the Bight of Benin which covers about 160 km of the State's coastline. Delta is an oil and agricultural producing state of Nigeria, situated in the region known as the Delta State, South-South geopolitical zone with a population of 4 098 291 (males: 2 674 306 and females: 2 024 085) (National Population Commission, 2006) (Table 1).

Table 1 Population of local government areas in Delta State

Delta State is generally low-lying without remarkable hills. The State has a wide coastal belt interlace with rivulets and streams, which form part of the Niger-Delta.

The Major ethnic groups are Urhobos, Isoko, Ukwuani, Itsekiri, Ezon, Enuani-Igbos, and Ika. Major crops grown include cassava, yam, coco yam, potato, plantain/banana, oil palm, rubber and pepper. Animal husbandry and fishing activities are also prevalent in the state. It experiences average rainfall of about 2 000 mm per annum with an average monthly temperature of 30.4℃-36.4℃ and a relative humidly varying from 56%-86% per annum. Delta state is divided into three agricultural zones namely, Delta South, Delta central and Delta North.

A systematic sampling technique was used to compose a sample size of 410 respondents. This was done as the followings: one out of every 10 000 people was selected, that is, the sampling fraction for the systematic was one ten-thousandth. Thus the sampling fraction was 1 divided by 10 000. Data used for this study were collected using well structured interview schedule.

The following methods of data analyses were employed in the study.

Descriptive statistical techniques such as tables, percentages, means and standard deviation were used to aid interpretation and easy explanation.

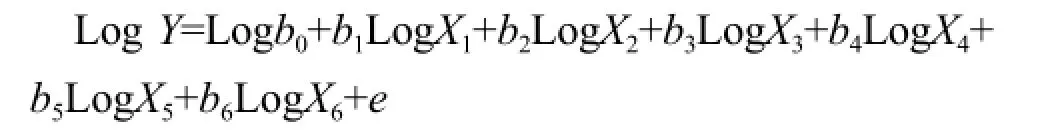

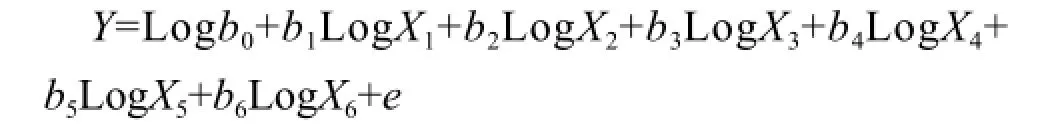

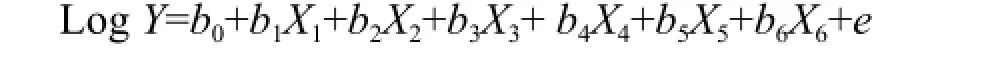

Different functional forms were fitted to determine the factors influencing bush meat consumption in Delta State, Nigeria (semi-log, double log, linear and exponential models).

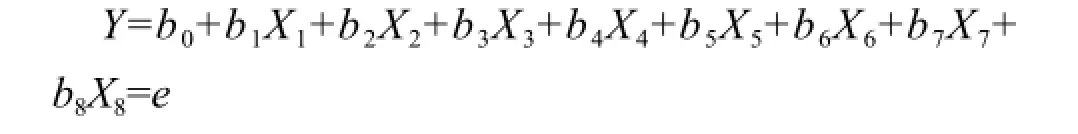

Mathematically, the linear regression model was implicitly specified as the followings:

While the explicit form of the linear relationship was given as:

Where,

Y=Physical quantity of bush meat consumed in kilograms.

The double log function was explicitly expressed as:

The semi log form was expressed as:

The exponential functional form was expressed as:

Where,

Log=natural logarithm

All other variables were as defined before.

However, the linear functional form was chosen as it had the highest R2, the highest number of significant variables and minimal standard error. F-value of the linear functional form also fitted the data.

Results and Discussion

Socio economic characteristic of respondentsMost of the respondents were middle-aged. They were mostly males, married, and a high proportion (about 91%) had one type of formal education or the other; majority were in low income class.

Bush meat consumption pattern

The result of the study indicated that almost all the respondents (402) representing about 98% were formally consuming bush meat. Only about 2% of the respondents were previously not consuming bush meat. However, the consumption pattern of bush meat when the survey was carried out had changed dramatically.

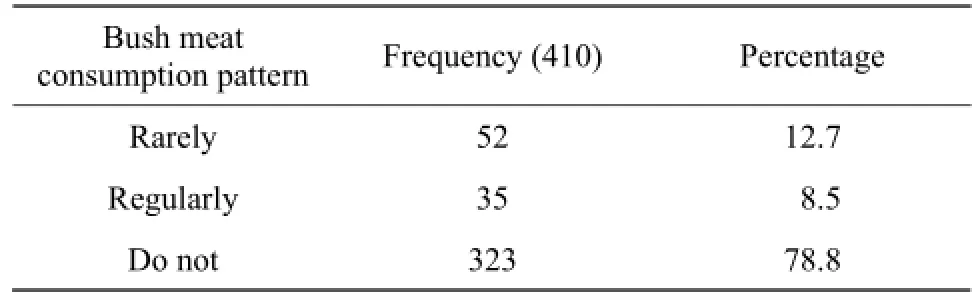

Table 2 showed the current bush meat consump-tion pattern in Delta State, Nigeria. The findings revealed that as many as 323 individuals, representing 78.8% of the respondents did not consume bush meat. Only about 12.7% and 8.5% occasionally and regularly consumed bush meat, respectively. It was therefore very obvious that people no longer consume bush meat in Delta State as before. This finding was supported by that of Bassey et al. (2010) who asserted that the consumption of game meat was dwindling recently.

Table 2 Bush meat consumption pattern

Types of bush meat consumed/reared in study area

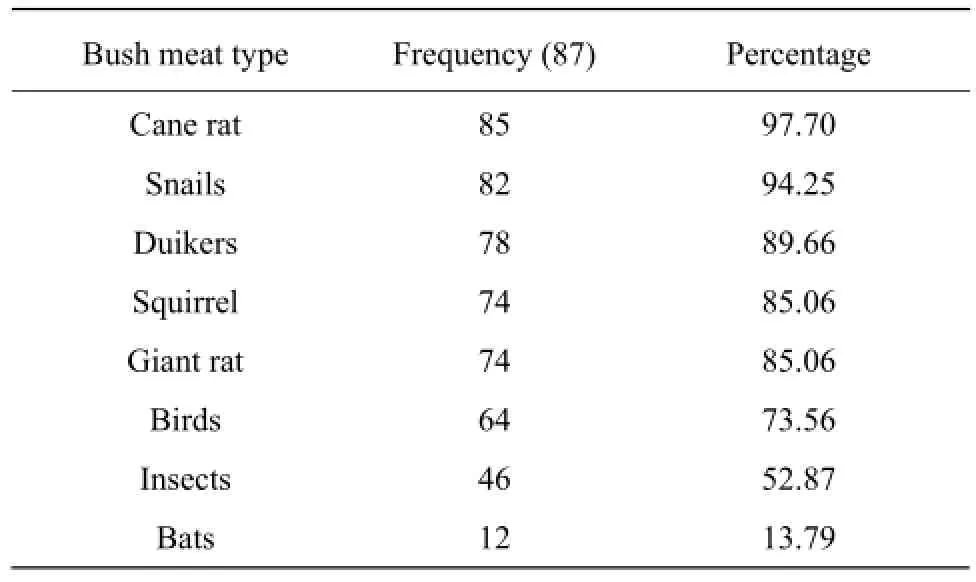

Table 3 showed the various types of game consumed by respondents in the study area. The results indicated that the predominant bush meat consumed in the area was cane rat (97.70%). According to small and minilivestock training news and update (2012), the meat of grasscutter was relished all over the world and it was consumed by people across all social and religious barriers. It is a very important source of protein with very low cholesterol level. This could probably be one of the reasons adduced for its widespread consumption in the area. The next commonly consumed game species was the African giant snails (Achatina and Archachatina). About 94.25% of the respondents consumed snails. CTA (2008) indicated that snails were highly prized in the coastal countries of west and central Africa. Other types of minilivestock consumed in the Delta State include: duikers (89.66%), squirrel (85.06%), giant rat (85.06%), birds of various species (73.56%), insects (52.87%) and bats (13.79%).

Table 3 Type of bush meat consumed in study area

Constraints militating against bush meat consumption in Delta State

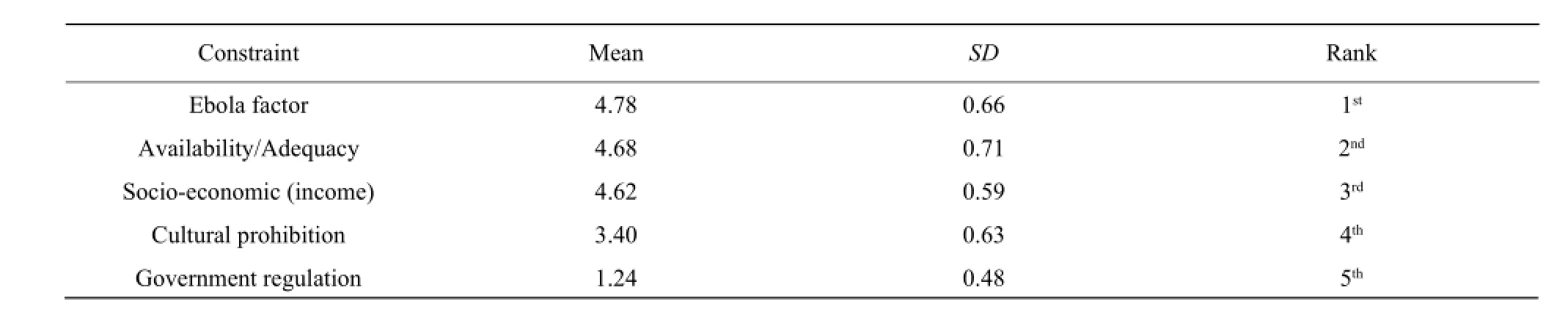

Several factors were adduced for the drop in the consumption of bush meat in the study area. These factors are: Table 4 showed respondents' perceived constraints to the consumption of bush meat in Delta State. Respondents asserted that Ebola crisis (X=4.88) was the most serious constraint militating against their consumption of bush meat. Other constraints to the consumption of bush meat include availability/ adequacy of supply (X=4.68), socio-economic status (X=4.62) and cultural practices (X=3.40). Governmental regulation was not a serious barrier to the consumption of bush meat in Delta State.

Test of hypothesis

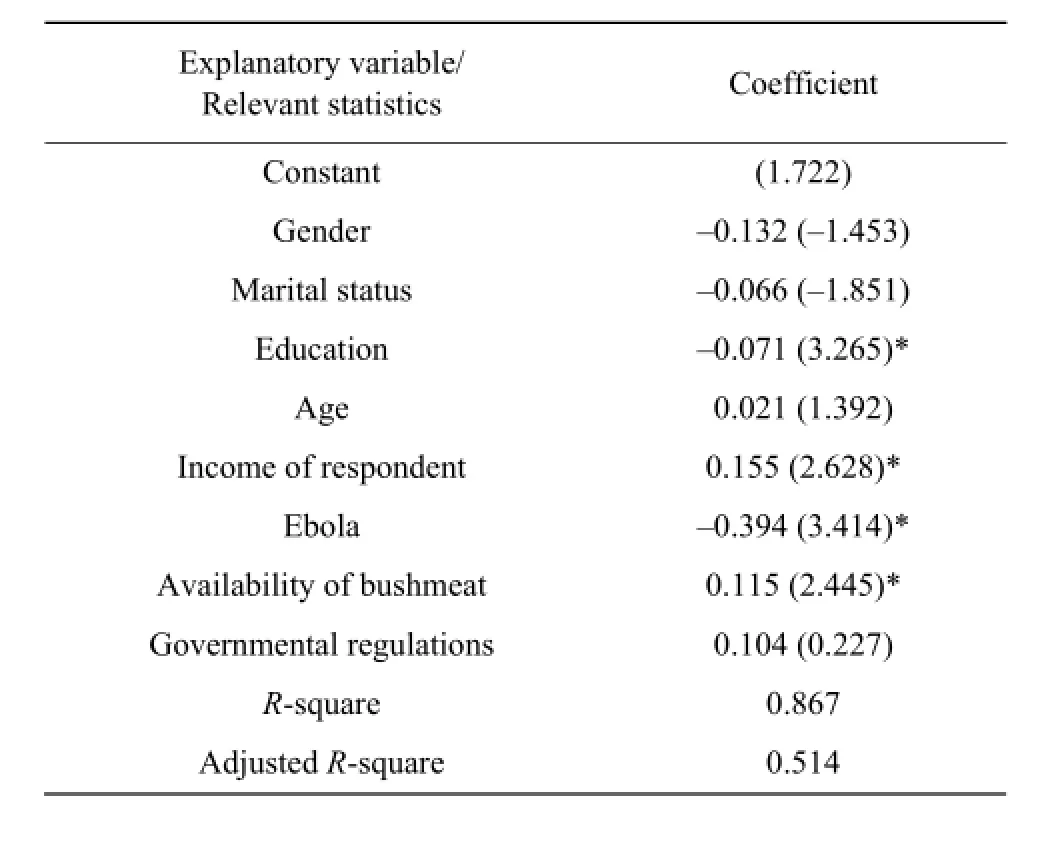

This section showed the result of multiple regression analysis determining the significance of relationships of several factors perceived to affect the consumption of bushmeat. In Table 5, the results of the relationship between some characteristics of respondents/other factors and bushmeat consumption was depicted. To determine the factors influencing bushmeat consumption in Delta State, tests were first conducted to check the presence of any multicolinearity between the independent/explanatory variables. The tests indicated that there was no presence of multicolinearity. As a result, all the explanatory or independent variableswere entered and the equation fitting the linear regression model was estimated. The explanatory variables relating to the consumption of bush meat were gender (X1), marital status (X2), educational level (X3), age (X4), income (X5) Ebola crisis (X6), availability of bush meat (X7) and governmental regulations (X8).

Table 4 Constraint militating against the consumption of bush meat

Table 5 Relationship between some variables and consumption of bush meat

R-square is the degree at which the relationship between the dependent variable and a combination of the independent variables can be predicted. From Table 5, R2value of 0.867 indicated that the explanatory variables could explain 86.7% of the variations in the dependent variable. Thus, the multiple regression analysis is regarded as being accepted.

The coefficient for education (X3), income (X5), Ebola (X6) and availability of game (X7) were found to be significant at 5% level of significance, indicating that these variables were important factors influencing the consumption of bush meat in the study area. However, the coefficients of level of education and Ebola factor were negative and significant, suggesting respondents with higher education and aware of the Ebola disease are not likely to consume bush meat. This could be attributed to the fact that the higher the level of education, the more likely the respondent would heed to government campaign to desist from eating bush meat. On the other hand, the coefficient of the availability of bush meat was positive, indicating that if bush meat was available, respondents were likely to consume it.

Conclusions and Recommendation

From the findings of the study, it was concluded that bush meat which was formally relished by majority of Deltans was now almost unacceptable due to avalanche of factors like dread of Ebola disease, inavailability of game, educational level and income, which significantly affected the consumption of bush meat. From the findings of the study, the following recommendations were made as the followings:

(1) There should be enlightenment campaign to sensitize the populace that there were no more Ebola crises in Nigeria.

(2) Since bush meat was an important source of protein, extension delivery services on how to domesticate game species should be available to farmers.

(3) Communities should be encouraged to domesticate game species like the cane rat, giant snails and other game species at both backyard and commercial levels. To this end research on the management practices, especially on their housing, feeding and disease control, of these animals should be intensified and findings disseminated to farmers. If these recommendations were implemented, bush meat would be readily available to the people without the danger of extinction and the threat of deadly diseases.

Adeola M O, Decker E. 1987. Wildlife utilisation in rural Nigeria. In Clers B D. Proceedings of the international symposium and conference on wildlife management in Sub-Saharan Africa, 6-13 October, Harare, Zimbabwe. pp. 512-521.

Ajayi S S. 1979. Utilisation of forest wildlife in West Africa. Misc/79/26, Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rome. pp. 79.

Ajayi S S. 1977. Live and carcass weight of giant rat Cricetomys gambianus. Waterhouse and domestic rabbit Oricielagus cuniculus L. E Afri Wildlife Journal,15: 223-227.

Anadu P A. 1987. Progress in the conservation of Nigeria's wildlife. Biological Conservation,41: 237251.

Anstey S. 1991. Wildlife utilisation in Liberia, report of a survey undertaken for the World Wide Fund for Nature. Gland Switzerland, Unpbl.

Asibey E O A. 1986. Wildlife and food security. Pages prepared for FAO Forestry Department, Rome.

Asibey E O A. 1987. The grasscutter. Paper prepared for the Ghana Livestock Show 87, Accra. pp. 4.

Asibey E O A. 1989. Bushmeat production in West Africa. Paper presented at the symposium on extractive economies in tropical forests: a course of action, Nov 30-Dec 1 1989, Washington DC, USA. pp. 34.

Asibey E O A, Child G. 1990. Wildlife management for rural development in sub-Saharan Africa. Unasylva,41: 3-10.

Asibey E O A, Eyeson K K. 1973. Additional information on the importance of wild animals as food source in Africa south of the Sahara, Bongo, Journal of the Ghana Wildlife Society,1(2): 13-17.

2006 Population Census. Federal Republic of Nigeria, National Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 2009-03-25.

Bassey E, Nkonyu L, Dunn A. 2010. A reconnaissance survey of the bushmeat trade in eight border communities in south-east Nigeria. Unpublished report to the Arcus Foundation and the WCS Nigeria Program.

Bushmeat Crisis Task Force. Retrieved 14 February 2015. Document on the breeding of the giant African snail (Achatina achatina).

Butynski T M, von Richter W. 1972. In: Botswana most of the meat is wild. Unasylva,26: 2429.

CBS News (AP. October 29, 2014). Retrieved 14 February 2015. Ebola scares West Africans away from bush meat.

Chihongo A W. 1992. Non-wood products-pilot country study on NWFP for Tanzania. Paper Prepared for the Regional Expert Consultation on Non-wood Forest Products for English-speaking African Countries, Arusha, Tanzania. Commonwealth Science Council. pp. 57.

Cowlishaw G, Mendelson S, Rowcliffe J. 2005. Evidence for postdepletion sustainability in a mature bushmeat market. Journal of Applied Ecology,42(3): 460-468.

Crawford M A. 1968. Possible use of wild animals as future sources of food in Africa. The Veterinary Record 16 March 1968. pp. 305-314.

Crawford M A. 1974. The case for new domestic animals. Oryx, 12. pp. 35-36.

Cremoux P. 1963. The importance of game meat consumption in the diet of sedentary and nomadic peoples of the Senegal River Valley. In: Conservation of nature and natural resources in modern African States, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Dei G J S. 1991. The dietary habits of a Ghanaian farming community. Ecology of Food and Nutrition,25: 29-49.

Fa J E, Currie D, Meeuwig J. 2003. Bushmeat and food security in the Congo Basin: linkages between wildlife and people's future. Environmental Conservation,30(1): 71-78.

Falconer J. 1992. People's uses and trade in non-timber forest products in Southern Ghana: a pilot study. Report Prepared for the Overseas Development Administration.

FAO. 1989. Forestry and nutrition: a reference manual. Rome.

Feer F. 1993. The potential for sustainable hunting and rearing of gamein tropical forests. In: Hladik C M, Hladik A, Linares O F. Tropical forests, people and food. The Parthenon Publishing Group, Paris. pp. 691-708.

Gartlan S. 1987. The Korup regional management plan: conservation and development in the Ndian Division of Cameroon. World Wildlife Fund Report No 25: 37-79, Gland Switzerland.

Golden C D, Fernald L C H, Brashares J S, et al. 2011. Benefits of wildlife consumption to child nutrition in a biodiversity hotspot. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,108(49): 19653-19656.

Hladik C. 1987. Se nourrir en fores équatoriale: anthropologie alimentaire différentielle des populations des régions forestières humides d Afrique. Research Team Report No. 263. Paris, CARS.

Hogenboom, Melissa (October 18, 2014). Ebola: Is bushmeat behind the outbreak?. BBC News. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Hoogesteijn Reul R. 1979. Productive potential of wild animals in the tropics. Wld Anim Rev,32: 18-24.

Ichikawa M. 1993. Diversity and selectivity in the food of the Mbuti hunter-gatherers in Zaire. In: Hladik C M, Hladik A, Linares O F. Tropical forests, people and food. The Parthenon Publishing Group, Paris. pp. 487-504.

Infield M. 1988. Hunting, trapping and fishing in villages within and on the periphery of the Korup National Park. Korup N. P. Socioeconomic survey prepared for WWF 43 pp.

Jeffrey S. 1977. How Liberia uses wildlife. Oryx, XIV,2: 168-173.

Keita J D. 1993. Non-wood forest products in Africa: an overview. Paper Prepared for the Regional Expert Consultation on Non-wood Forest Products for English-speaking African Countries, Arusha, Tanzania, Council Commonwealth Science Council. pp. 12.

Lahm S A. 1993. Ecology and economics of human/wildlife interaction in Northeastern Gabon. New York University, New York, USA.

Maliehe T M. 1993. Non-wood forest products in South Africa. Paper prepared for the Regional Expert Consultation on Non-wood Forest Products for English-speaking African Countries, Arusha, Tanzania. Commonwealth Science Council. pp. 52.

Martin G H G. 1983. Bushmeat in Nigeria as a natural resource with environmental implications. Environmental Conservation,10: 125-132.

McGregor J. 1991. Woodland resources: ecology, policy and ideology. University of Loughborough.

MSF USA. 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014. Struggling to Contain the Ebola Epidemic in West Africa.

Murphy S P, Allen L A. 2003. Nutritional importance of animal source foods. Journal of Nutrition,133: 3932S-35S.

Nasi R, Brown D, Wilkie D, et al. 2008. Conservation and use of wildlife-based resources: the bushmeat crisis. Technical Series no. 33, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, and Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor.

Ntiamoa-Baidu Y. 1987. West African wildlife: a resource in jeopardy. Unasylva,39: 27-35.

Ntiamoa-Baidu Y. 1992. Local perceptions and value of wildlife reserves to communities in the vicinity of forest national parks in Western Ghana. In: Protected area development in south-west Ghana report by the Oxford Environment and Development Group, UK.

Nyirenda R W S. 1993. Non-wood forest product development in Malawi. Paper Prepared for the Regional Expert Consultation on Non-wood Forest Products for English-speaking African Countries, Arusha, Tanzania. Commonwealth Science Council.

Prescott-Allen C, Prescott-Allen R. (1982). What's wildlife worth? Economic contributions of wild plants and animals to developing countries. An Earthscan Paperback.

Richter W V. 1970. Wildlife and rural economy. In: Botswana S W. Botswana Notes and Records.

Sale J B. 1981. The importance and values of wild plants and animals in Africa. Report prepared for IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Skinner J D. 1967. An appraisal of the eland as a farm animal in Africa. Animm Breed Abstr,35: 177-186.

Skinner J D. 1973. An aopraisal of the status of certain antelopes for game ranching in South Africa. Z Tier Z Ziichtioigsbiol,90(3): 263-77.

Small and mini-livestock training, news and update (2012). Posted 30th June 2012 by donsmart 2.

Smith V E. 1979. Household food consumption in rural Sierra Leone. Nutrition Planning, Information Service, Michigan State, Ann Arbor, USA.

Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) (2008). Mini-livestock keeping: think big with mini-livestock. Field report from Togo 2008. (online) Retrieved on 12th March, 2015. http:// www.ledis-ifas ufi.edu.FAO 48.htm no 133- February, 2008.

Teleki G, Baldwin L. 1981. Sierra Leone's wildlife legacy: options for survival. Zoonooz,54: 2128.

Topps J N. 1975. Behavioural and physiological adaptation of wild animals and their potential for meat production. Proc Nutr Soc,31(I): 85-93.

Tutu K A, Ntiamoa-Baidu Y, Asuming-Brempong S. 1993. The economics of living with wildlife in Ghana. Report prepared for the World Bank, Environment Division. pp. 85.

Tutu K A, Ntiamoa-Baidu Y, Asuming-Brempong S. 1996. The economics of living with wildlife in Ghana. In: Boj? J. The Economics of Wildlife: Case Studies from Ghana, Kenya, Namibia and Zimbabwe, 11-38.

Verschuren J. 1983. Conservation of tropical rain-forest in Liberia: recommendations for wildlife conservation and national parks. Report prepared for IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Vincke P P, Singleton M, Diouf P S D. 1987. Chasse alimentaire chez les Séreers du Siné (Senegal). Paper Presented at the International Symposium and Conference on Wildlife Management in Sub-Saharan Africa, Harare, Zimbabwe, 6-13 October (FAO/International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, pp. 653-656.

Von Richter W, Butynski T. 1973. Hunting in Botswana. Botswana Notes and Records,5: 191-208.

Wilson K B. 1990. Ecological dynamics and human welfare: a case study of population, health and nutrition in Southern Zimbabwe. University of London.

Q95

A

1006-8104(2015)-03-0067-12

Received 8 May 2015

Ebewore S O, male, Ph. D, senior lecturer, engaged in the research of rural community and sociology. E-mail: solomonebewore@yahoo.com

Journal of Northeast Agricultural University(English Edition)2015年3期

Journal of Northeast Agricultural University(English Edition)2015年3期

- Journal of Northeast Agricultural University(English Edition)的其它文章

- Design of Non-contact On-load Automatic Regulating Voltage Transformer

- Chinese Comprehensive Rural Reform: Institutional Vicissitude, Theoretic Framework and Content Structure

- Preparation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells and Cardiomyocyte Differentiation Induced with Retinoic Acid and Ascorbic Acid

- Contents of Trace Metal Elements in Cow Milk Impacted by Different Feedstuffs

- Predatory Efficacy of Cotton Inhabiting Spiders on Bemisiatabaci, Amrascadevastans Thripstabaci and Helicoverpa armigera in Laboratory Conditions

- Effect of Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens on Growth of Greenhouse Tomato and Rhizosphere Microbial Community