Beyond prostate, beyond surgery and beyond urology: The “3Bs” of managing non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms

Qixing Song , Pul Abrms *, Yingho Sun ,*

a Department of Urology, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China

b Bristol Urological Institute, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, UK

KEYWORDS Male;Lower urinary tract symptoms;Benign prostatic hyperplasia;Benign prostatic obstruction;Detrusor overactivity;Detrusor underactivity;Prostate surgery;Comorbidities

Abstract Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), consisting storage, voiding and postmicturition symptoms, is a comprehensive definition involving symptoms that may occur due to several causes. Instead of simply focusing on the enlarged prostate, more attention has to be paid to the entire urinary tract as well as multiple system comorbidities.Therefore,prostate surgery alone does not necessarily provide adequate management and cross-disciplinary collaborations are sometimes required. Based on current literature, this paper proposes the“3Bs” concept for managing non-neurogenic male LUTS, namely, “beyond prostate”, “beyond surgery” and “beyond urology”. The clinical application of the “3Bs” enables urologists to carry out integrated, individualized and precise medical care for each non-neurogenic male LUTS patient.

1. Introduction

It has became increasingly evident that“l(fā)ower urinary tract symptoms” (LUTS) is a comprehensive term, encompassing storage, voiding and post-micturition symptoms, and was proposed more than 20 years ago to emphasize that there are other causes than the prostate for LUTS[1,2].Over the past decade,the European Association of Urology(EAU)has replaced the title “Guidelines on benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) ” with “Guidelines on the treatment of nonneurogenic male LUTS”, in 2011, and now in 2017 the EAU Guidelines are “Guidelines on management of nonneurogenic male LUTS, incl. benign prostatic obstruction(BPO)” and have been since 2013 [3-6]. This major modification has highlighted that the urinary tract should be viewed as a whole, and the treatments need to be tailored for each individual patient. In this new perspective, we propose the “3Bs” of managing non-neurogenic male LUTS based on a current literature review, namely,“beyond prostate”, “beyond surgery” and “beyond urology”.

2. Beyond prostate

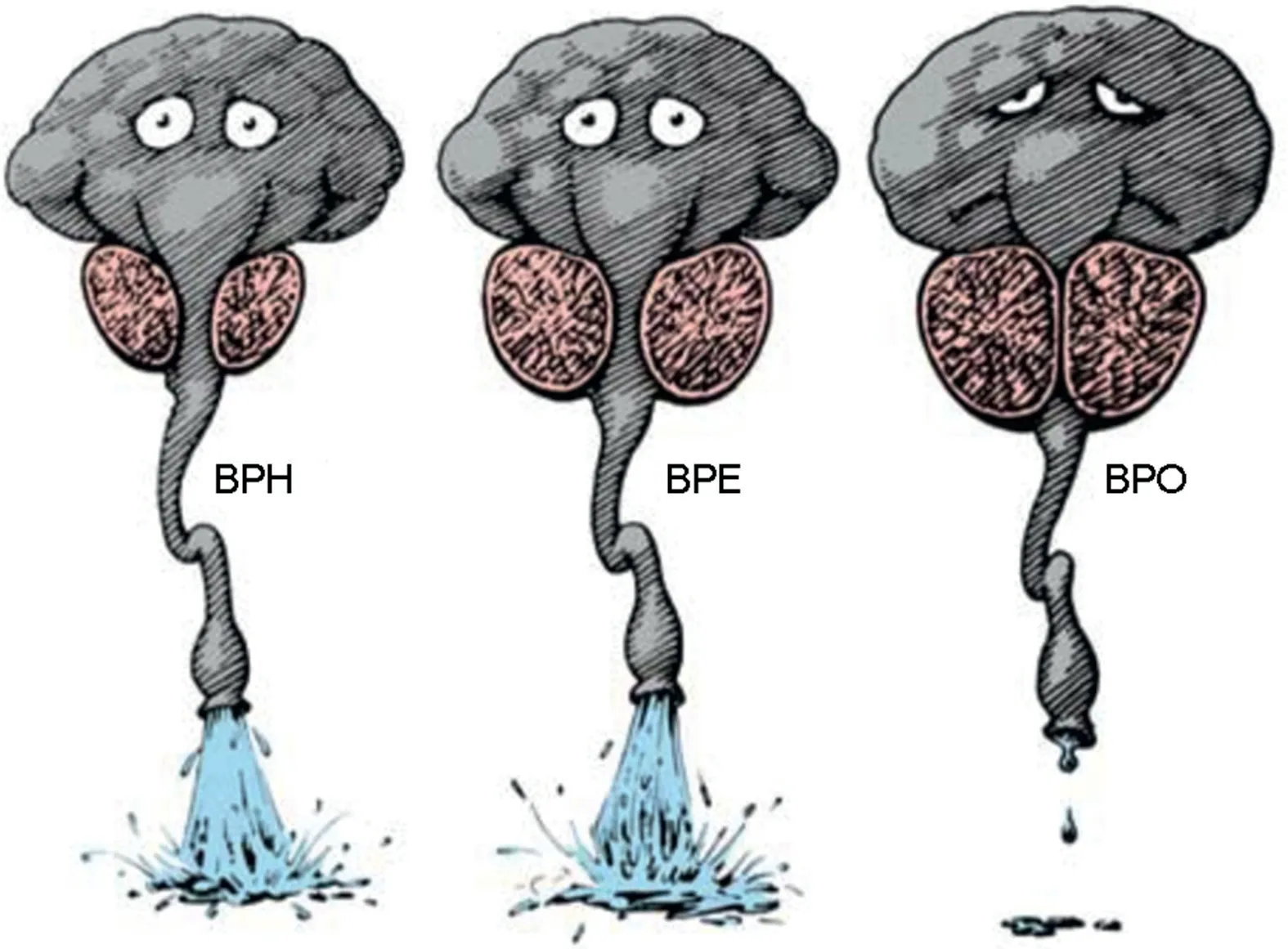

Although the term LUTS is in universal use,the term BPH is still misused. In the literature there are many references that talk about the “BPH man” or “clinical BPH” but these terms have variable meanings and do not help patient management. In itself the histological appearance BPH does not cause LUTS. Also as the prevalence of histological BPH is very high: 50% in men at 50-60s and nearly 90% in men above 80 years, the term “BPH” used to describe a symptomatic man is meaningless in most men with LUTS.Only in a minority of men does histological BPH develop into benign prostatic enlargement (BPE), and then further progress to create BPO and cause LUTS (Fig. 1). Approximately 25% of men with histological BPH develop BPO.Although 50%of men with BPH develop to BPE,only half go on to get BPO[7-10].These data indicate that BPO causing LUTS should be distinguished from BPH and BPE which frequently exist, but do not cause LUTS in the absence of BPO. To emphasize this point, BPH is a histology diagnosis that correlates poorly with clinical symptoms [2]. Clinical experience also tells us a small prostate can sometimes cause severe obstruction, whereas a big prostate does not necessarily cause obstruction or LUTS. With that in mind,when the prostate is proved to be “innocent”, other possible causes of LUTS should to be taken into account,such as, overactive bladder due to detrusor overactivity during filling, detrusor underactivity (DU) during voiding,urethral stricture, stone diseases, and chronic pelvic pain syndrome,etc,depicted graphically(Fig.2)in the 2017 EAU guidelines [6].

Moreover, patients with sustained BPO can also have bladder dysfunction which may be due to abnormalities of neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, receptors and signaling pathways in the urothelium,detrusor smooth muscle and/or interstitial cells [9]. Oelke and colleagues [11]demonstrated that of 1418 man with “clinical BPH”, detrusoroveractivity(DO)wasfoundin864 patients(60.9%)andwas independently associated with the grade of bladder outlet obstruction.In another study on 2039“LUTS/BPH”patients,58.7%of them presented DU during urodynamic studies[12].DO can give rise to bothersome overactive bladder storage symptoms (urgency, frequency, urgency incontinence and nocturia),while DU leads to voiding symptoms(weak stream anddysuria)whichcanonlybedistinguishedfromBPOusingan invasive pressure-flow study.

In addition, BPO related lower urinary tract dysfunction can jeopardize the upper urinary tract. Traditionally, using serum creatinine as the diagnostic criteria for chronic kidney diseases (CKD), 11% of “BPH” patients also had impaired renal function[13].Note that compared to serum creatinine,estimated glomerular filtration rate(eGFR)is a more sensitive and accurate indicator because it takes age, sex,race and cystatin C into account [14,15]. More recently,different studies have reported that among male LUTS patients, 18.0%-31.9% of them demonstrated moderate to severe eGFR reduction(<60 mL/min/1.73 m2)[16,17].In this regard, when dealing with the lower urinary tract abnormalities, it is wise to stay vigilant at all times on patients’upper urinary tract as well,and follow the EAU recommendation that ultrasound of the urinary tract and renal assessment should be done when indicated, for example when there is a large post void residual.

Figure 1 Cartoon depicting the differences among benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), benign prostatic enlargement(BPE)and benign prostatic obstruction(BPO).Reproduced from Housami F et al., 2008 [23].

Figure 2 Common urological causes of male lower urinary tract symptoms. Reproduced, with permission, from EAU guidelines on management of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms(LUTS),incl.Benign Prostatic Obstruction,2017 [6].

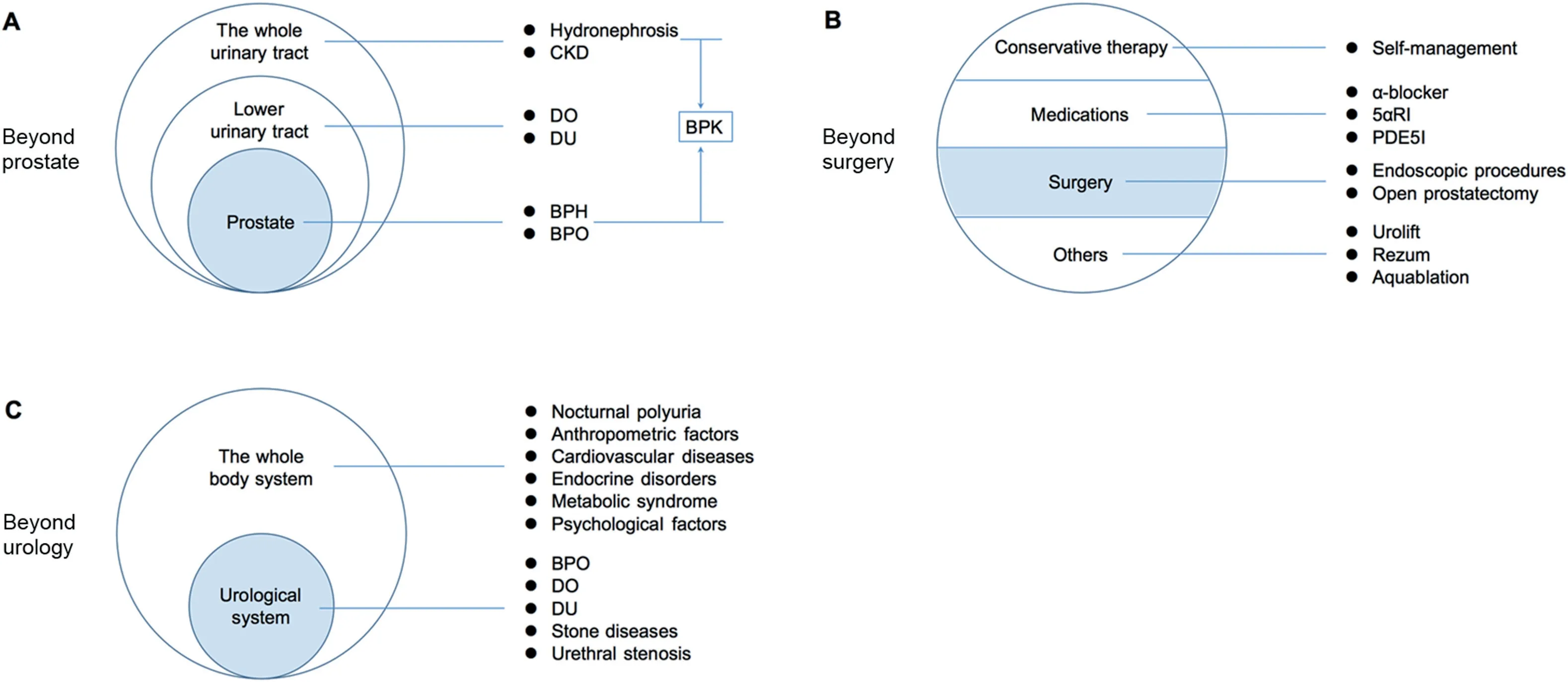

From the aforesaid,when faced with a man with LUTS it is possible that the man’s symptom complex could be associated with disease progression and the development of complications.Instead of simply focusing on the enlarged prostate,we need to see a bigger picture and probably shift our conventional notion of“BPH”to“bladder,prostate and kidney(BPK)”when managing male LUTS patients(Fig.3A).

3. Beyond surgery

Conventionally, patients with increased pr ostate volume would have been labelled as candidates for surgery without hesitation. However over the past 2 decades, studies from different countries have reported that the rate of both open and minimal invasive prostate surgery has been decreasing each year. A survey based on national inpatient database (represents roughly one-fifth of the total inpatients of the United States) demonstrated that the total usage of prostate surgeries decreased between year 2002 through 2012(from about 4000 to 2500 cases per year)[18].In Iceland,the application of transurethral resection of the prostate(TURP)on men with“BPH”over 50 peaked in 1992(30 procedures per 1000 men),then gradually reduced each year and ended at 3.4 procedures per 1000 men in 2008[19].Furthermore,a report from Spain also showed a 17.6%decrease in benign prostate surgery from 1992 to 2002[20].

Why are fewer prostatectomies being performed?

The first and probably the most straightforward explanation for this phenomenon is the introduction of medical therapy.One of the above mentioned studies indicated that the descending trend of TURP procedures carried out since 1992 was accompanied by an ascending adoption of α1-adrenergic antagonists and 5α-reductase inhibitors which are both first line agents recommended by the EAU guidelines [6,19]. Besides, the use of muscarinic receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors and β3-adrenergic agonists, and mono- or combination therapy offer alternative options. Therefore, patients who used to be treated by surgery are being given oral medications.

Moreover, behavioural and lifestyle self-managing are being increasingly offered to patients concurrently with watchful waiting and standard treatment as recommended by the EAU guidelines [6]. A randomized control study indicated that patients allocated to self-managing group experienced lower treatment failure rate, less symptom severity, and higher quality of life than those without [21]. However, whether self-management, on its own, can reduce or postpone the need for surgery remains unclear.

Additionally, surgery should now be reserved for “Mr.Right” who presents with bothersome LUTS attributed to BPO, possibly refractory to conservative/medical treatment. Note that performing TURP on unobstructed patients,or those with LUTS due to DU does not yield superior outcomes in both urodynamic parameters and symptoms compared to those who have no treatment[22].In addition,though TURP substantially improves maximum flow rate,International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and quality of life, the incidence of unrelieved postsurgical storage symptoms is 31%-59% at 6 months follow-up and up to 10%patients report de novo DO [23]. Thus, surgery can only achieve its maximum benefits in carefully selected patients and even then post-surgical medication treatment may be needed.

Last but not the least, the emerging new technologies provide much less invasive solutions and may have potential impact on current treatment paradigms. These novel technologies include prostatic urethral lift, radiofrequency generated thermal therapy, aquablation, prostatic artery embolization, implantable nitinol device, and electromagnetic field therapy, just to name a few [24].Generally, these approaches are minimal or non-invasive with less morbidity, have very short or no hospitalization and can be done under local anesthesia. Though sufficient data have validated their initial efficacy and safety, more randomized control trials are required to elucidate their long-term equivalence or superiority over the existing endoscopic procedures.In short, we have versatile treatment options beyond surgery and they must be individualized based on clinical findings and the degree of symptom bother (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3 Schematic illustrated the“3Bs”of managing non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms,i.e.,beyond prostate(A),beyond surgery(B)and beyond urology(C).The bullet points in the right column represent examples of the pointed categories in the circles. 5αRI, 5α-reductase inhibitors; BPK, bladder prostate and kidney; BPO, benign prostatic obstruction; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; CKD, chronic kidney diseases; DO, detrusor overactivity; DU, detrusor underactivity; PDE5I, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors.

4. Beyond urology

Numerous data exists to demonstrate that LUTS is highly related to lifestyle factors,systemic disorders and geriatric diseases (Fig. 3C). Heavy smokers are prone to have more severe LUTS and significant symptom deterioration, but sufficient daily physical activity reduces LUTS exacerbation during follow-up [25,26]. Reports from the International Consultation on Incontinence Research Society revealed that LUTS and metabolic syndrome (comprising cardiological aberrations, hypertension, central obesity, dyslipidaemia and type 2 diabetes) share multiple pathophysiological mechanisms and correlate with each other [27]. In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with an increased incidence of “BPH”, and urgency urinary incontinence is the predominant LUTS in these patients[28,29]. Furthermore, anthropometric, psychological, and hormonal factors should also be taken into consideration during management [7].

Nocturia is a good example to illustrate the multifactorial feature of LUTS. (1) Patients with congestive heart failure, chronic renal insufficiency, hepatic failure,nephrotic syndrome, autonomic neuropathy or hypoalbuminemia may have third-space fluid sequestration which can result in nocturia due to nocturnal polyuria,when more than 33%of the 24 h urine volume is produced at night.(2)Circadian secretion of arginine vasopressin can be compromised when there are hypothalamic-pituitary axis abnormalities which can also lead to nocturia. (3) Sleeping disorders (such as, restless leg syndrome and obstructive sleep apnoea)are also highly related to increased nighttime urinary frequency.(4)Patients with reduced renal function,uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or diabetes insipidus may have 24 h polyuria,generating both daytime frequency and nocturia. (5) Modification of some living habits, including reducing evening fluid intake, stopping smoking and vigorous physical exercise, can alleviate nocturia and improve quality of life [30,31].

Hence one can see that urologists need to think beyond urology and seek cross-disciplinary collaborations so as to offer sufficient clinical care for patients with LUTS and associated comorbidities.

To sum up,“beyond prostate”highlights the importance of keeping an eye on the bladder function and upper urinary tract; “beyond surgery” emphasizes that we have various choices of self-management strategies,medications and novel approaches which should be personalized accordingly; and “beyond urology” reminds us that LUTS has multifactorial causes including systematic comorbidities. The clinical application of the “3Bs” enables urologists to carry out integrated, individualized and precise medical care for non-neurogenic male LUTS patients.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Qixiang Song, Paul Abrams,Yinghao Sun.

Data acquisition: Qixiang Song.

Drafting manuscript: Qixiang Song.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Qixiang Song, Paul Abrams, Yinghao Sun.

Final approval of manuscript: Qixiang Song, Paul Abrams,Yinghao Sun.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the permission from the EAU guidelines office to publish Fig. 2 in this paper.

Asian Journal of Urology2019年2期

Asian Journal of Urology2019年2期

- Asian Journal of Urology的其它文章

- Asynchronous abdominal wall and sigmoid metastases in clear cell renal cell carcinoma:A case report and literature review

- Compliance in patients with dietary hyperoxaluria: A cohort study and systematic review

- Dose escalation of external beam radiotherapy for high-risk prostate cancer-Impact of multiple high-risk factor

- Effect of warm bladder irrigation fluid for benign prostatic hyperplasia patients on perioperative hypothermia, blood loss and shiver: A meta-analysis

- Is Retzius-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy associated with better functional and oncological outcomes?Literature review and meta-analysis

- Systemic treatment for metastatic prostate cancer