Development and postnatal neurogenesis in the retina:a comparison between altricial and precocial bird species

Guadalupe álvarez-Hernán, José Antonio de Mera-Rodríguez, Yolanda Ga?án,Jorge Solana-Fajardo, Gervasio Martín-Partido, Joaquín Rodríguez-León,Javier Francisco-Morcillo,

Abstract The visual system is affected by neurodegenerative diseases caused by the degeneration of specific retinal neurons, the leading cause of irreversible blindness in humans.Throughout vertebrate phylogeny, the retina has two kinds of specialized niches of constitutive neurogenesis: the retinal progenitors located in the circumferential marginal zone and Müller glia. The proliferative activity in the retinal progenitors located in the circumferential marginal zone in precocial birds such as the chicken, the commonest bird model used in developmental and regenerative studies, is very low. This region adds only a few retinal cells to the peripheral edge of the retina during several months after hatching,but does not seem to be involved in retinal regeneration. Müller cells in the chicken retina are not proliferative under physiological conditions, but after acute damage some of them undergo a reprogramming event, dedifferentiating into retinal stem cells and generating new retinal neurons. Therefore, regenerative response after injury occurs with low efficiency in the precocial avian retina. In contrast, it has recently been shown that neurogenesis is intense in the retina of altricial birds at hatching. In particular, abundant proliferative activity is detected both in the circumferential marginal zone and in the outer half of the inner nuclear layer. Therefore, stem cell niches are very active in the retina of altricial birds. Although more extensive research is needed to assess the potential of proliferating cells in the adult retina of altricial birds, it emerges as an attractive model for studying different aspects of neurogenesis and neural regeneration in vertebrates.

Key Words: altricial; birds; circumferential marginal zone; Müller glia; postnatal neurogenesis; precocial regeneration; retinogenesis

Introduction

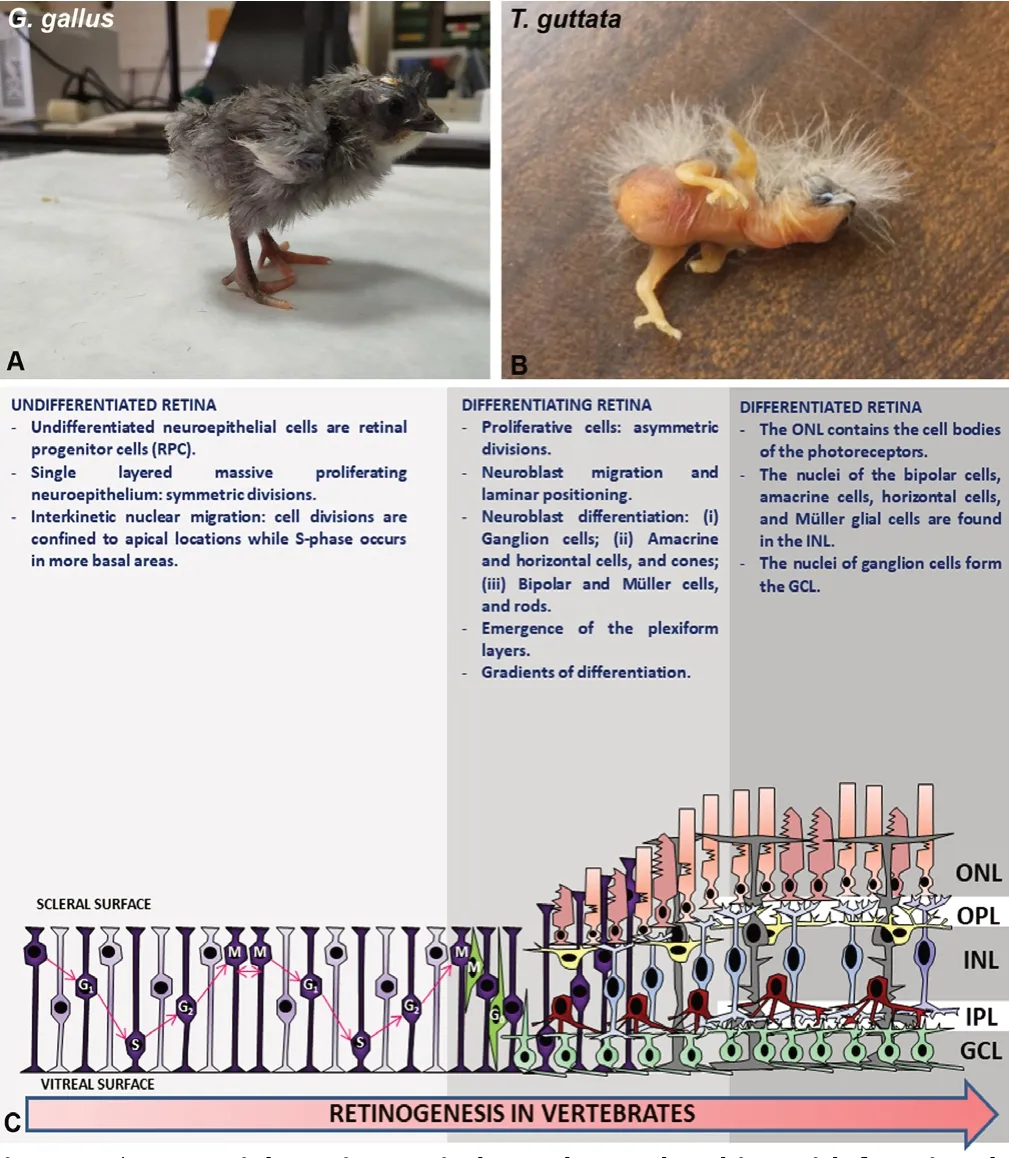

Birds are categorized along a precocial-to-altricial spectrum depending on behavioural and morphological maturation of hatchlings. At hatching, precocial birds are covered with down that is soon replaced by adult feathers. They also have open eyes and a well-developed musculoskeletal system(Figure 1A). In contrast, altricial hatchlings have little or no downy plumage on their skin, are blind, have less developed locomotion organs, and are highly reliant on parental care(Nice, 1962;Figure 1B).

Embryological studies have also confirmed substantial developmental differences between altricial and precocial birds (Murray et al., 2013; de Almeida et al., 2015). Precocial birds seem to reach early stages in development in less time than altricial birds (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951; Murray et al., 2013). Furthermore, several maturational features occur at later stages in the altricial birds than in the precocial birds (Murray et al., 2013; de Almeida et al., 2015; álvarez-Hernán et al., 2018, 2020), and, while different tissues mature at later stages of development in altricial embryos, this period is primarily characterized by growth in precocial birds(Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951; Murray et al., 2013).

Precocial birds also differ from altricial birds in the timing of brain structures differentiation (Charvet and Striedter,2011). Thus, several brain regions in altricial birds are relatively immature at hatching (Striedter and Charvet, 2008).Therefore, altricial birds exhibit a great post-hatching brain growth associated with intense neurogenesis in certain brain regions such as the telencephalon (DeWulf and Bottjer, 2005;Striedter and Charvet, 2008; Charvet and Striedter, 2009,2011). Neurogenesis is intense inT. guttatachicks during the first week of life, but this process persists even into adulthood(DeWulf and Bottjer, 2005; Charvet and Striedter, 2009).Those authors conclude that postnatal maturation of brain structures facilitates learning in altricial birds. Therefore, the brain of altricial birds emerged as an influential model for the study of adult neurogenesis.

The visual system is a powerful model for advancing in knowledge about ontogenetic differences among vertebrates.Visual system morphogenesis and retinogenesis are well conserved throughout the vertebrate phylogeny (see below).However, while most of these developmental features occur during the embryonic period in precocial birds, some of these species complete retinal development during postnatal life.In precocial Chondrichthyes (Bejarano-Escobar et al., 2013;Sánchez-Farías and Candal, 2015, 2016), Osteichthyes (Candal et al., 2005, 2008; álvarez-Hernán et al., 2019), reptiles(Francisco-Morcillo et al., 2006), and mammals (Loeliger and Rees, 2005; Gudurich-Fuchs et al., 2009), retinogenesis is completed during embryological stages. In contrast, in altricial fish (Doldán et al., 1999; Pavón-Mu?oz et al., 2016; álvarez-Hernán et al., 2019) and mammals (Rapaport et al., 2004;Bejarano-Escobar et al., 2011), retinal development occurs postnatally.

Regarding avian retinal development, it is well known that events such as cell differentiation (Prada et al., 1991; Martín-Partido and Francisco-Morcillo, 2015; de Mera Rodríguez et al., 2019) and cell death (Cook et al., 1998; Marín-Teva et al.,1999; Francisco-Morcillo et al., 2014) within the precocial retina occur embryonically. At birth, the layers of the retina of precocial birds are clearly distinghished and shows differentiated cells (Prada et al., 1991; Rojas et al., 2007; de Mera-Rodríguez et al., 2019). Neurogenesis is almost absent in the chicken retina, and is restricted to a few cells located in the circumferential marginal zone (CMZ) (Fischer and Reh,2000). In contrast, many features of immaturity have been described in the retina of newly hatched altricial birds (Bagnoli et al., 1985; Rojas et al., 2007; álvarez-Hernán et al., 2018,2020). Recent studies conducted in our laboratory have shown that neurogenesis is intense in the retina of newly hatched altricial birds (zebra finch,Taeniopygia guttataVieillot 1817)(álvarez-Hernán et al., 2018, 2020).

In this review, we shall describe the variation in the developmental timetable of visual system ontogeny from the altricial/precocial perspective. We shall also highlight the remarkable variation in proliferative activity of avian cell progenitors in the retina of altricial and precocial birds at hatching and during the first postnatal days.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

Studies cited in this review were found on the PubMed database, between December 2019 and February 2020, using the search terms: adult neurogenesis, retinogenesis, visual system development, altricial birds, precocial birds, retinal progenitors, retinal regeneration, altricial development,precocial development, and various combinations of the above terms.

Morphogenesis, Histogenesis, and Cell Differentiation in the Vertebrate Retina

The vertebrate retina is formed embryonically from the brain and plays a key role in vision. This sensory tissue consists of several layers of neurons with two neuropils where synaptic contacts occur. There are three layers of cell somata which contain the cell nuclei: outer nuclear layer (ONL), inner nuclear layer, and ganglion cell layer; there are also two layers that contain synaptic connections between axons and dendrites: outer plexiform layer and inner plexiform layer (Figure 1C). The retina consists of six major types of neurons that include the rod and cone photoreceptors, the horizontal, bipolar, and amacrine cell interneurons, and the retinal ganglion cells (Figure 1C). Furthermore, Müller cells are considered the main type of glia in the vertebrate retina. These cells are radially oriented and span the entire thickness of the retina (Figure 1C).

Figure 1 |Precocial species are independent at hatching with functional visual and locomotor systems in contrast to those of altricial species.G. gallus (A) and T. guttata (B) newly hatched animals. Schematic representation of the vertebrate retinogenesis process showing the most important events of cell differentiation and histogenesis (C). During the first stage of retinal development, this tissue is composed of neuroepithelial cells that undergo both symmetric and asymmetric divisions. Neuroblasts produced by neuroepithelial cells migrate to different sites before their differentiation (C). Figure 1 is sourced from our laboratory (unpublished). GCL:Ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; IPL: inner plexiform layer; ONL:outer nuclear layer; OPL: outer plexiform layer.

During early stages of neurulation, the retina originates from a bilateral evagination of diencephalon that gives rise to optic vesicles. Inductive signals from the ectoderm control invagination of the optic vesicles, resulting in the formation of double-layered, cup-shaped structures - the optic cups (Chow and Lang, 2001). The external layer of the optic cup forms the retinal pigment epithelium, whereas the internal sheet of cells forms the pseudostratified retinal neuroepithelium.These neuroepithelial cells proliferate in a peculiar manner:with their cytoplasmic processes extending from the internal limiting membrane to the pigment epithelial end, the nuclei of these retinal cell progenitors engage in a vitreal-toscleral movement, undergoing, at specific depths within the neuroepithelium, different phases of the cell cycle (Figure 1C). This nuclear movement is called interkinetic nuclear migration. In the undifferentiated retina, mitosis (M-phase)occurs in the scleral surface, near the presumptive retinal pigment epithelium. During the period of symmetric cell division, each neuroepithelial cell divides to produce two daughter cells that extend a process toward the opposing vitreal surface while maintaining contact with the scleral surface. Then, asymmetric cell division generates daughter cells that either re-enter the cell cycle or leave it to become post-mitotic migrating neuroblasts that differentiate into one of seven classes of retinal cells. This process of cell determination and differentiation is termed retinogenesis(Xiang, 2013; Amini et al., 2018) (Figure 1C).

Timing Differences during Visual System Development in Altricial and Precocial Birds

Many of the developmental events that occur during visual system embryogenesis in birds begin earlier in the retina of precocial species than in altricial species. Thus, the optic vesicle and optic cup formation and the emergence of the plexiform layers occur at later stages in theT. guttataretina(álvarez-Hernán et al., 2018) than in the chicken (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951). Furthermore, the first differentiating ganglion cells are detected in theG. gallusretina at HH13(48-52 hours of incubation) (Prada et al., 1991; Snow and Robson, 1994), while in theT. guttataretina, the first ganglion cells become post-mitotic at St24 (108 hours) (álvarez-Hernán et al., 2020). The onset of visinin expression, an early marker of photoreceptor differentiation, in the chicken ONL occurs at HH27 (120 hours) (Bruhn and Cepko, 1996; Bradford et al.,2005), while in theT. guttataretina it is first detected at St28(132 hours) (álvarez-Hernán et al., 2020). Finally, the onset of expression of Prox1, a transcription factor that is expressed during early horizontal cell differentiation, is detected in theT. guttataretina at St34 (172 hours) (álvarez-Hernán et al.,2020), while the first Prox1-immunoreactive progenitors in the chicken retina are detected at HH30 (156 hours) (Edqvist and Hallb??k, 2004). Thus, morphogenesis, histogenesis, and cell differentiation in the developingT. guttataretina are delayed with respect toG. gallus, a precocial bird species.

Retinal Maturity at Hatching

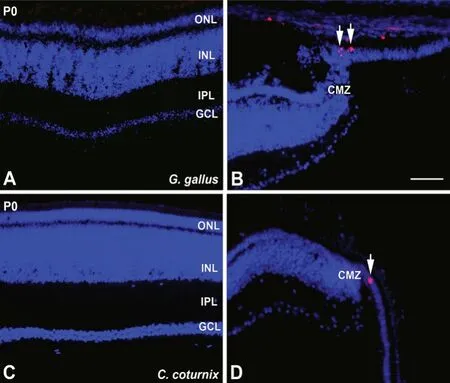

Precocial birds hatch with a fully differentiated and functional retina (Fischer and Reh, 2000; Kubota et al., 2002). Mitotic figures, detected with antibodies against phospho-histone H3, were absent in the central retina of newly hatched individuals in the chicken (Figure 2A) and in the quail (Figure 2C). However, sparse phospho-histone H3-immunoreactive mitotic figures are found in the CMZ in both precocial species(Figure 2BandD). This proliferative activity in the peripheralmost region of the retina in hatchlings and adults of these birds suggests on-going growth of the retina during postnatal life (Fischer et al., 2014). These proliferative cells also express retinal progenitor markers. Intra-ocular injections of different growth factors can greatly enhance the proliferative activity in the CMZ (Fischer and Reh, 2003). Furthermore, a subpopulation of cells located in a specific region of the ciliary body also have neurogenic potential and can be stimulated by several growth factors to proliferate and differentiate into retinal neurons (Fischer and Reh, 2003).

Müller glia plays a essential role in the maintenance of the retinal structure and participates in essential homeostatic processes in the developing and mature retinal tissue(Bejarano-Escobar et al., 2017). These cells have a significant proliferative and neurogenic capacity under physiological (Julian et al., 1998; Pavón-Mu?oz et al., 2016)and experimental conditions (Bernardos et al., 2007) in the fish retina. However, Müller glia are not proliferative in the healthy bird retina at hatching. Avian Müller cells can exhibit neurogenic properties under the effect of acute damage or by the addition of specific growth factors in the uninjured chicken retina (Fischer and Reh, 2000). These stimuli induce proliferation of Müller cells and re-initiation of the expression of retinal progenitor markers (Fischer and Reh, 2000).Therefore, Müller glia need to be stimulated to acquire the proliferative phenotype in precocial birds.

Figure 2|Immunodetection of pHisH3 in G. gallus (A, B) and C. coturnix (C,D) in the retina of newly hatched animals.pHisH3 immunoreactivity is absent in the central retina in both species (A, C).Sparse immunoreactive mitotic figures are observed in the most peripheral retina (arrows in B, D). CMZ: Circumferential marginal zone; GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; IPL: inner plexiform layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer. Scale bar: 50 μm. Figure 2 is sourced from our laboratory (unpublished).

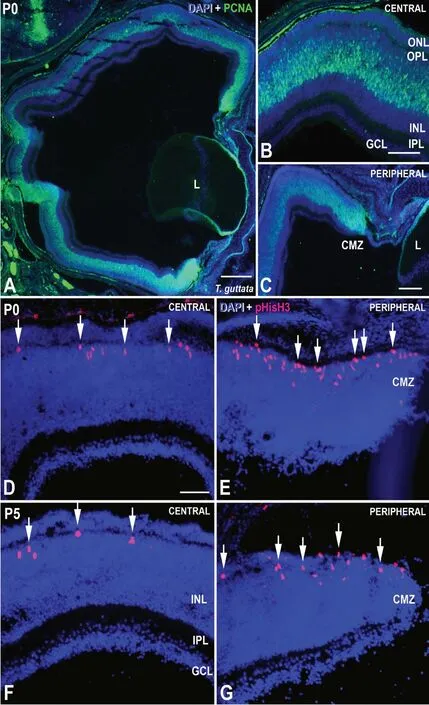

At hatching, the central retina of altricial birds such as the zebra finch (T. guttata) shows the typical layering of the mature tissue. However, sings of immaturity are found such as a increased thickness of the ganglion cell layer, very thin plexiform layers, and photoreceptors displaying immature morphology (Rojas et al., 2007; álvarez-Hernán et al., 2018,2020). Nevertheless, the main feature of immaturity is that neurogenesis is intense in the altricial retina in newly hatched animals (Figure 3). Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is expressed by retinal progenitors in the avian retina (Fischer and Reh, 2000; álvarez-Hernán et al., 2018, 2020). Thus,on hatching day (post-hatching day 0, P0), abundant PCNAimmunoreactive nuclei are detected in the outer half of the inner nuclear layer, the region where the bipolar/Müller cell bodies are located (Figure 3AandB). Bipolar and Müller cells are the last cell types that exit the cell cycle in the developing retina (Amini et al., 2018). It has been described that strong expression of PCNA is detected in early degenerating cells(Borges et al., 2004). During perinatal stages, sparse pyknotic nuclei are detected in the inner nuclear layer of altricial birds(unpublished data) and therefore, some of the PCNA-positive nuclei could correspond to apoptotic cells.

Furthermore, the peripheral-most retina shows abundant PCNA immunoreactive nuclei (Figure 3AandC), suggesting that the altricial retina is still undergoing intense growth via the addition and integration of concentric rings of newly generated cells. The PCNA immunostaining observed in the P0T. guttataretina is similar to that described in the E12G.gallusretina, about nine days before hatching (Ghai et al.,2008).

Also, abundant mitotic activity is found in the ventricular retinal surface in both the central (Figure 3D) and peripheral(Figure 3E) retina of newbornT. guttata, but also in hatchling chicks (P5) (Figure 3FandG), showing that neurogenesis is intense in the altricial retina after hatching (álvarez-Hernán et al., 2018, 2020).

Conclusion

The neural retina has been the tissue of choice to study the main aspects of embryonic and postnatal neurogenesis.Current research in teleost fish and amphibians demonstrates that adult neural stem cells exist in the retina of these species(Araki, 2014; Pavón-Mu?oz et al., 2016; Madelaine and Mourrain, 2017). These populations of cells are crucial to the function of this region of the visual system, since they can both permit physiological cellular turnover and replace cells lost from injury or disease. Proliferating cells within the mature retina are also present in other vertebrates, including reptiles(Todd et al., 2015; Eymann et al., 2019) and birds (Fischer and Reh, 2000). These non-mammalian species provide excellent comparative models for examining the molecular and cellular mechanisms of adult retinal stem cell maintenance and fate.Precocial birds such as the chicken or quail generate most retinal neurons prenatally, and neurogenesis in their posthatching retina is restricted to a few progenitor cells located at the peripheral retinal margin (Fischer and Reh, 2000).Müller cells are considered to be astrocyte-related cells that acquire retinal stem cells characteristics after injury (Hoang et al., 2020). In our current work (álvarez-Hernán et al., 2018,2020), we have shown that the patterns of proliferation reveal that neurogenesis is intense in the retinas of altricial birds at hatching and even at early stages post-hatching.Strong proliferative activity is detected in both the CMZ and the bipolar/Müller cell layer. Therefore, the altricial retina continues to grow during post-embryonic stages, even until day 5 after hatching. Furthermore, the differentiation of bipolar and Müller cells extends into the post-hatching period.

Figure 3 |PCNA (A-C) and pHisH3 (D-G) immunoreactivity in the P0 (A-E)and P5 (F, G) T. guttata retina.Abundant PCNA-positive nuclei are detected in the bipolar/Müller cell layer (A-C) and in the CMZ (A, C). Abundant pHisH3-positive cells are found in the vitreal surface of the central (D, F) and peripheral (E,G) retina. CMZ:Circumferential marginal zone; GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; IPL: inner plexiform layer; L: lens; ONL: outer nuclear layer; OPL: outer plexiform layer. Scale bars: 500 μm in A; 100 μm in B and C; 50 μm in D-G.Figure 3 is sourced from our laboratory (unpublished).

It is necessary to determine whether neurogenesis is still detected in the retina of juveniles or adult altricial birds, but long-life neurogenesis in the retina of altricial birds opens up an additional field beyond developmental neurogenesis.It could constitute a powerful tool to determining how postembryonic neurogenesis is regulated under physiological and regenerative conditions. The understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in neurogenesis could have crucial implications for regenerative therapies. In conclusion, the retina of altricial birds such as canaries or zebra finches,models used for the study of brain plasticity, may constitute a useful model system for eye research, both in development and, given its postnatal neurogenic activity, regeneration research.

Author contributions:GAH, JAMR, YG, JSF, GMP, JRL and JFM wrote and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial support:GAH was a recipient of a Fellowship from the Universidad de Extremadura. This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (BFU2007-67540), Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (CGL2015-64650P), Dirección General de Investigación del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (BFU2017-85547-P),and Junta de Extremadura, Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional, “Una manera de hacer Europa” (GR15158, GR18114, IB18113).

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2021年1期

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2021年1期

- 中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Oxidative stress battles neuronal Bcl-xL in a fight to the death

- The role of peptidase neurolysin in neuroprotection and neural repair after stroke

- Cathepsins in neuronal plasticity

- Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: lessons from cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers

- Progenies of NG2 glia: what do we learn from transgenic mouse models ?

- The NLRP3 inflammasome: a potential therapeutic target for traumatic brain injury