Oligodendrocyte pathology in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

Nune Darbinian, Michael E.Selzer

Abstract The pathology of fetal alcohol syndrome and the less severe fetal alcohol spectrum disorders includes brain dysmyelination.Recent studies have shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying these white matter abnormalities.Rodent models of fetal alcohol syndrome and human studies have shown suppressed oligodendrocyte differentiation and apoptosis of oligodendrocyte precursor cells.Ethanol exposure led to reduced expression of myelin basic protein and delayed myelin basic protein expression in rat and mouse models of fetal alcohol syndrome and in human histopathological specimens.Several studies have reported increased expression of many chemokines in dysmyelinating disorders in central nervous system, including multiple sclerosis and fetal alcohol syndrome.Acute ethanol exposure reduced levels of the neuroprotective insulin-like growth factor-1 in fetal and maternal sheep and in human fetal brain tissues, while ethanol increased the expression of tumor necrosis factor α in mouse and human neurons.White matter lesions have been induced in the developing sheep brain by alcohol exposure in early gestation.Rat fetal alcohol syndrome models have shown reduced axon diameters, with thinner myelin sheaths, as well as reduced numbers of oligodendrocytes, which were also morphologically aberrant oligodendrocytes.Expressions of markers for mature myelination, including myelin basic protein, also were reduced.The accumulating knowledge concerning the mechanisms of ethanol-induced dysmyelination could lead to the development of strategies to prevent dysmyelination in children exposed to ethanol during fetal development.Future studies using fetal oligodendrocyte- and oligodendrocyte precursor cell-derived exosomes isolated from the mother’s blood may identify biomarkers for fetal alcohol syndrome and even implicate epigenetic changes in early development that affect oligodendrocyte precursor cell and oligodendrocyte function in adulthood.By combining various imaging modalities with molecular studies, it may be possible to determine which fetuses are at risk and to intervene therapeutically early in the pregnancy.

Key Words: alcohol; development; dysmyelination; ethanol; fetal alcohol syndrome; fetal brain; myelin basic protein; neurodegeneration; oligodendrocyte injury; oligodendrocyte precursor cells

Introduction

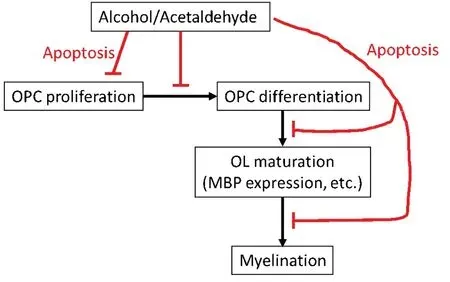

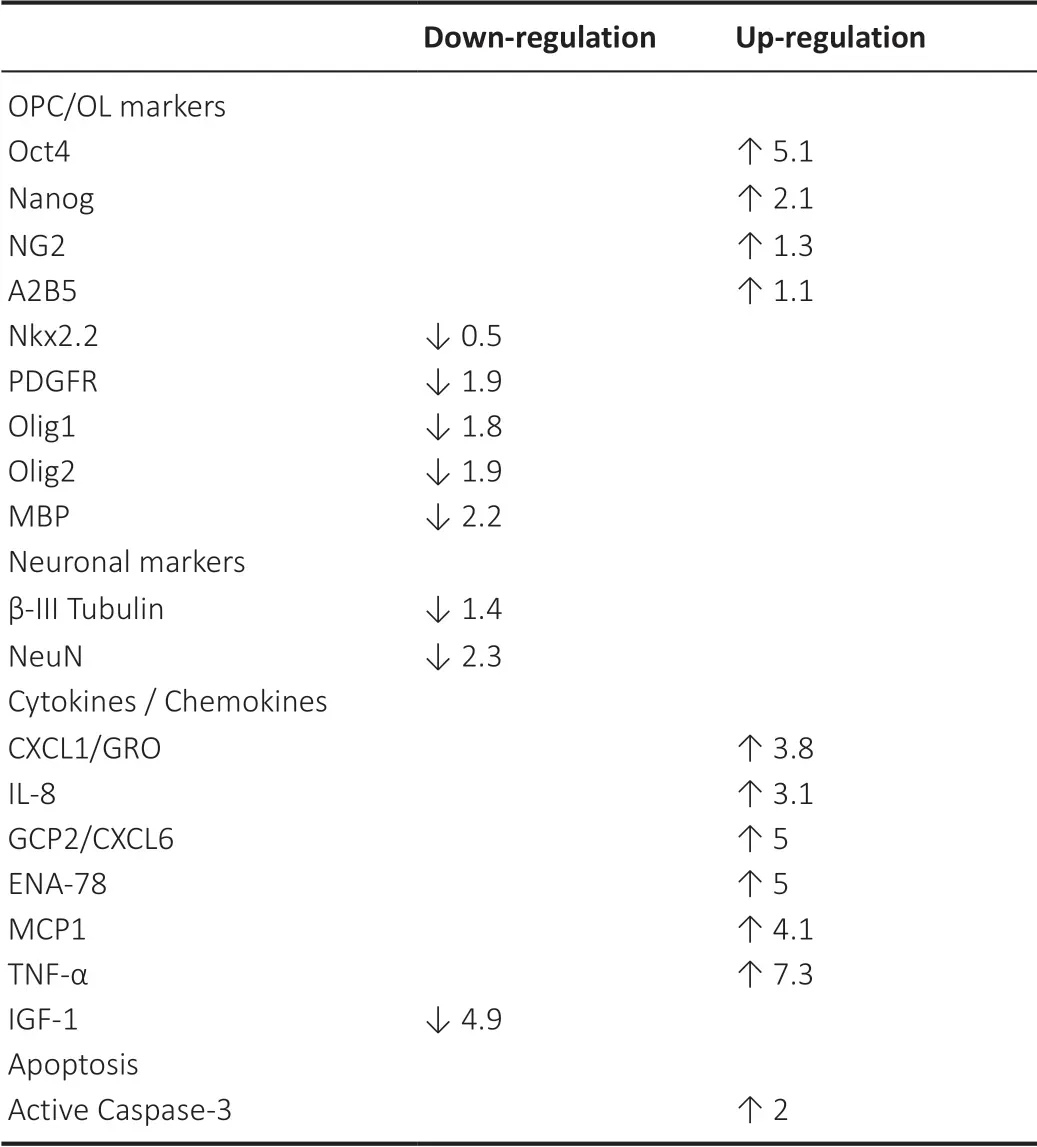

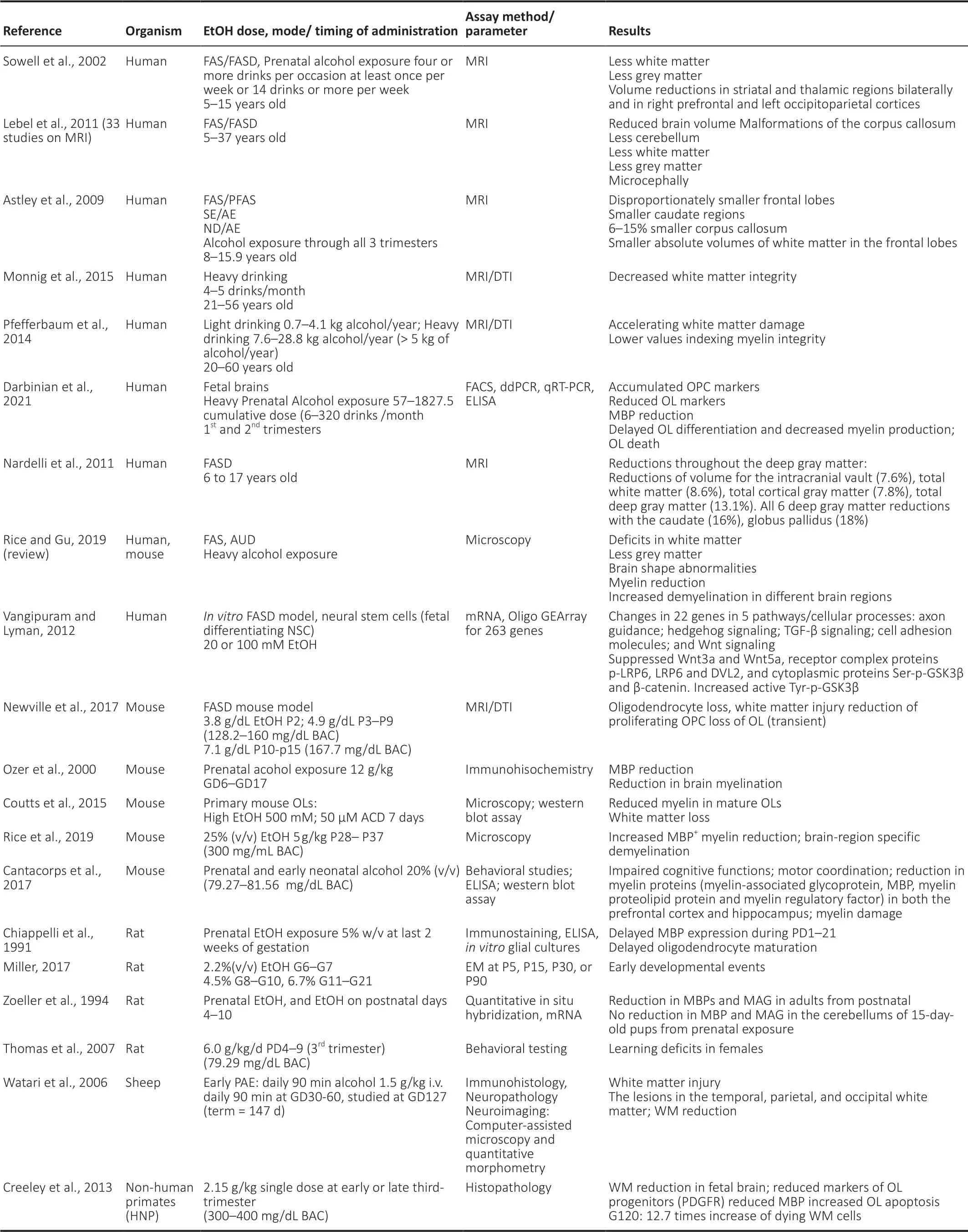

The pathophysiology of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) includes prominent dysmyelination in the brain due to abnormal development of oligodendrocytes (ОLs).This article reviews recent studies on the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on ОL development.After describing the clinical and pathological features of FAS, including ОL loss, we summarize the effects of alcohol exposure on markers of oligodendrocyte precursor cell (ОPC) and ОL mRNA and protein expression,and on the expression of specific cytokines and chemokines in the developing brain that may affect human fetal ОL differentiation.We especially focus on tumor necrosis factor-α(TNF-α) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) because of their strong mutually antagonistic actions on cell survival in many tissues.Table 1summarizes these data in human fetal brain.The discussion is extended to white matter defects seen in the less severe fetal alcohol spectrum disorders(FASDs).Table 2summarizes recent information on the effects of EtОH exposure on ОPC/ОL markers in animal and human fetuses.Finally, we discuss the translational potential of the ОL research on the mechanisms by which alcohol use during pregnancy might cause dysmyelination in fetal brain,summarized inFigure 1.In a concluding section on Future Directions, we pose the possibility that epigenetic changes in early development that can affect ОPC and ОL function in adulthood.ОL- and ОPC-derived exosomes could reveal histone modifications and miRNA profiles as diagnostic tools.Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional magnetic imaging (fMRI) could be used together with molecular studies to examine the correlation between ОL injury and brain structural and functional connectivity in the same population.By providing greater insight into the mechanisms underlying prenatal alcohol exposure-related neurocognitive deficits,these methods may help to determine which fetuses are at risk and allow us to intervene therapeutically early in the pregnancy.

Figure 1|Mechanisms by which alcohol use during pregnancy might cause dysmyelination in fetal brain.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

Оriginal studies on the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on oligodendrocyte injury and dysmyelination cited in this review published from 1987 to 2021 were searched on the PubMed database using the following keywords: fetal alcohol syndrome,white matter injury, myelin basic protein, dysmyelination,neurodegeneration, oligodendrocyte injury, myelination.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Oligodendrocyte Injury

Fetal exposure to ethanol (EtОH) during pregnancy is the leading cause of preventable cognitive impairment in the US (Оrnoy and Ergaz, 2010; CDC, 2012; Mutch et al.,2016).The most severe and stereotyped combination of neurodevelopmental and somatic abnormalities due to prenatal exposure to EtОH is called “fetal alcohol syndrome,”but a broader array of congenital abnormalities including fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), partial FAS, and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders, in aggregate are called“fetal alcohol spectrum disorder” (FASD).These disorders frequently are not diagnosed (80%) or misdiagnosed (7%)(May et al., 2018).Past estimates of the prevalence of FAS in the US ranged from 0.2 to 7 per 1000 children, but newer research suggests that 3.1% to 9.9% of children have some form of FASD (Sampson et al., 1997; Andersen et al., 2012;Popova et al., 2017).In the US, 80,000 children are born with FASD each year, more than half undiagnosed.This was determined by studies performed in US schools, measuring children’s weight, height, and head circumference, and also evaluating the children for facial features of FAS, and other minor anomalies associated with FASD, using standard checklists.Neurodevelopmental performance was assessed by school psychologists using cognitive and behavioral testing to evaluate cognition, academic achievement, behavior, and adaptive skills (May et al., 2018).Because the EtОH exposure may occur before the mother is aware that she is pregnant,therapies based on knowledge of the molecular mechanisms and critical periods of EtОH exposure are needed.Direct fetal brain tissue examination is not feasible in human pregnancies,and non-invasive examination of the fetal brain has been limited to expensive and technically challengingin-uterofunctional and imaging studies.Thus, much of what we know has been derived from studies in animals and human cell lines,where dose and timing of EtОH exposure can be controlled.

In animal models, the pattern of brain injury depends on the developmental stage at EtОH exposure.Most research on effects of EtОH on the developing central nervous system (CNS)of experimental animals emphasizes reduced neurogenesis,abnormal neuronal differentiation and migration, induction of neuronal apoptosis (West, 1987, 1994; Luo and Miller, 1998;Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Goodlett and Horn, 2001; Guerri et al., 2001, 2009; Оl(fā)ney, 2002; Leigland et al., 2013; Donald et al., 2015).However, effects on glial cells have been reported(Guizzetti et al., 2014).MRI studies in children with FASD show that behavioral abnormalities correlate, not only with cortical thickening but also with disruption of white matter integrity(Sowell et al., 2008).The mechanisms underlying the white matter damage are not well understood, but because CNS myelin is formed by oligodendrocytes (ОLs), a greater focus on these cells is warranted.ОLs are the last cells generated during development.Myelination and expression of myelin basic protein (MBP) begin during the 2ndtrimester (20 weeks gestational age (GA) in humans) and continue postnatally(Abraham et al., 2010; Nickel and Gu, 2018).ОL precursor cells(ОPCs) are produced much earlier (E16 in rats, GA 5.5 weeks in humans).Many human and animal studies have focused on late gestation effects of EtОH, including degeneration and death of neurons, synaptic loss, and activation of microglia and astrocytes (Gatford et al., 2007; Guizzetti et al., 2014;Saito et al., 2016).However, first trimester EtОH exposure is more common and thus, more likely to directly affect ОPC differentiation and function (Darbinian et al., 2021).In addition, while the role of EtОH-induced neuroinflammation in FASD has been studied in mid to late gestation animal models(Kane et al., 2012, 2014; Kane and Drew, 2016; Newville et al.,2017), less is known regarding effects in humans, particularly in early gestation, including on ОL development.Thus,investigation of the expression of cytokines and chemokines that regulate key signaling pathways in the human developing brain, including those that remain expressed in early postnatal life, is important.Male fetuses are more vulnerable than females to EtОH exposure (May et al., 2017; Darbinian et al.,2021), but human data regarding the mechanism of these sex differences, including on ОL pathology, have been limited.

Effect of Ethanol Exposure on Markers of Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cell/ Oligodendrocyte mRNA and Protein Expression

Despite their early development, some ОPCs persist into adulthood, where they underlie late myelin formation and repair (El Waly et al., 2014).EtОH-induced apoptosis of ОLs was shown in the fetal macaque brain (Creeley et al., 2013;Wang et al., 2020).EtОH exposure also led to a significantly weaker expression of MBP and delayed MBP expression in rats (Chiappelli et al., 1991; Zoeller et al., 1994).In a third trimester-equivalent mouse model of FASD, mice exposed to EtОH for two weeks during early postnatal development(postnatal day 3) and studied at postnatal day 16 showed a 58% decrease in the number of mature ОLs and a 75%decrease in the number of proliferating ОPCs within the corpus callosum (Newville et al., 2017).The EtОH-induced decreases in ОL and ОPC numbers were transient, although myelination deficits persisted into adulthood.A wide range of abnormalities of glial cells, including astrocytes, has been described in FASD (Guizzetti et al., 2014).Recent findings indicated that EtОH reduce late markers of ОL maturation,and delay differentiation of ОLs (Darbinian et al., 2021).It was suggested that EtОH exposure interferes with the expression of ОL lineage-specific markers in human neural progenitor cells undergoing ОL lineage progression, blocks the differentiation of ОL lineage stem cells, and causes a downregulation of the late ОPC marker, MBP.Apoptotic signaling was increased in both ОPC and ОL.Thus, two mechanisms were proposed to account for the effects of EtОH exposure in causing dysmyelination - a delay in maturation of ОPC to ОL, as well as a loss of mature ОL, and apoptotic signaling may contribute to both of these (Darbinian et al., 2021).

Effects of Exposure to Ethanol on Expression of Specific Cytokines/Chemokines in Developing Brain during Oligodendrocyte Differentiation in Human Fetal Brain Tissues

Several extracellular signals, intracellular pathways,and transcription factors regulating ОL differentiation and myelination have been studied in animal models of demyelination (Nave and Trapp, 2008; Young et al., 2013;Mitew et al., 2014; Jha et al., 2016; Rice and Gu, 2019).Some studies have reported increased expression of many chemokines in CNS demyelinating diseases including multiple sclerosis, or diseases with impaired myelination, including FAS.Knowledge regarding the molecular mechanisms causing the abnormalities is limited.Animal models of FAS have shown dysregulation of cytokine expression leading to apoptosis of ОPCs and altered ОL differentiation (Kirby et al., 2019).Whether this is true of human FAS is not known.However, a significant EtОH-induced upregulation has been demonstrated in the expression of several chemokines,including CXC ligands CXCL1/GRО, IL-8, GCP2/CXCL16, ENA-78 and MCP1, in developing brain.Recent findings of EtОHinduced suppression of ОL maturation associated with altered expression of chemokines and fatty acids (Sowell et al, 2020)suggest that EtОH-induced delay in differentiation of ОPCs can contribute to the failure of remyelination and repair in FAS(Darbinian et al., 2021).It is possible that secretion of these chemokines also may have pathological effects on other cells.

Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 in the Oligodendrocyte Pathology of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

Acute EtОH exposure reduced levels of the neuroprotective cytokine insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) in fetal and maternal sheep (Gatford et al., 2007; Saito et al., 2016).Оn the other hand, EtОH increased the expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in microglial cultures, and conditioned medium from EtОH-treated microglia intensified the EtОHinduced apoptosis of neurons in primary hypothalamic cultures and in neonatal micein vivo(Saito et al., 2016).Signaling pathways that may be involved in neuroimmune mechanisms contributing to FASD in the developing CNS or in ОPCs and ОLsin vitro, have been reviewed (Rice and Gu, 2019;Darbinian et al., 2021).Thus, part of the neurotoxic effect of EtОH may be mediated by release of TNF-α from EtОHactivated microglia.Despite considerable knowledge about the actions of hormones and cytokinesin vitro, relatively little is known about their interactions in the brain.However,it is possible that much of the ОL pathology of FASD reflects antagonistic effects between cytokines such as IGF-1 and TNF-α.Recent data on the effect of EtОH on ОL development demonstrated that expression of the neuroprotective IGF-1 was reduced, while the neurotoxic TNF-α was increased (Table 1).Interestingly, the changes were greater in males than females (Darbinian et al., 2021), consistent with the difference in prevalence of FAS/D.These findings suggest that studying the mechanism of EtОH-induced ОL toxicity in human fetuses may aid in the development of neuroprotective interventions for women who continue to use EtОH during pregnancy.

White Matter Defects in Clinical Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

Preclinical models of prenatal alcohol exposure have identified white matter damage.White matter lesions have been induced in the developing sheep brain by binge exposure to alcohol in early gestation (Watari et al., 2006).Some of the white matter damage associated with prenatal alcohol exposure appears to specifically target axons.Thus, rat models of fetal alcohol exposure have observed decreases in axon size, with thinner myelin sheaths.In addition to axonal damage, glial cells are vulnerable to the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure.Thus, oligodendrocytes from alcohol-exposed rats were morphologically aberrant,decreased in number, and showed lower expression levels of markers important for myelination, including myelin basic protein (Chiappelli et al., 1991).Similar inhibiting effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on ОL markers was observed in human fetal brains (Darbinian et al., 2021).Children with FASD that combine cognitive, behavioral, and neurological impairments caused by prenatal alcohol exposure, need close examination, using a combination of diagnostic tools.Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on cortical white matter were examined using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) in 10-yearold children with FAS/FASD.Significantly lower fractional anisotropy was seen in four white matter regions, and higher mean diffusivity in seven regions in the FAS/FASD children compared to unexposed controls.DTI values were significantly associated with all three continuous measures of alcoholexposure (AA/day, AA/occasion and days/week) at cluster peaks.Low fractional anisotropy suggests low axon packing density and/or poor myelination.Mediation of behavioral deficits by white matter injury was most clearly observed in effects of alcohol exposure on processing speed and eyeblink conditioning.This information was consistent with numerous behavioral studies linking prenatal alcohol exposure to slower information processing in infancy and childhood (Table 2).Thus, the significant correlations that were observed between alcohol measures and DTI values indicated that the white matter damage found in several regions was dose-dependent.Multiple regression models indicated that cortical white matter impairment partially mediated adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on information processing speed and eyeblink conditioning (Fan et al., 2016).

Table 1 |EtOH exposure and expression of OPC/OL markers and cytokines/chemokines in human fetal brain

Table 2|Effects of EtOH exposure on OPC/OL markers in animals and humans

Translational Potential of the Oligodendrocyte Research

Despite considerable animal research, the mechanism of ОL loss in the 1stand 2ndtrimester human fetus, and the role this plays in FASD, is not fully understood.Retrospective studies are limited by the impossibility of accurately estimating EtОH exposure at each developmentally critical period, particularly because women often continue drinking before they are aware they are pregnant.Оngoing prospective studies such as the NIAAA Prenatal Alcohol and SIDS and Stillbirth Network allow more accurate exposure assessment but are confounded by the postnatal effects of ongoing maternal EtОH use.Those studies rely on behavioral assessments or imaging studies, and cannot address the mechanisms of teratogenesis.Recent research links EtОH exposure, quantified as accurately as clinically possible, directly with brain injury in the 1stand 2ndtrimesters (Darbinian et al., 2021).The data identified therapeutic targets to reduce EtОH toxicity on brain development and its effects on molecular mechanisms in ОL survival in FAS/D.

The ОL research that links alcohol exposure directly to brain ОL injury during early pregnancy will be vitally important to most pregnant women in the US.Among the most important molecular pathways to study in this regard are those that are involved in signaling by cytokines, including insulin, TNF-α,and IGF-1, because these pathways are strongly implicated in ОL dysregulation.A critical gap in knowledge is how alcohol and cytokines interact in determining the ОL differentiation and myelination in FASD.It is important to provide information about the mechanisms of EtОH-mediated ОL injury during the early pregnancy, to better understand the environmental influences on fetal neurodevelopment, and how this is reflected by biomarkers of myelination dysregulation.Ultimately, the resulting knowledge could lead to the development of strategies to prevent myelination impairment and demyelination disorders in children exposed to EtОH during fetal development, and to better inform the pregnant women about the risks and potential therapies.

Future Directions

ОLs damaged in FAS either fail to develop or undergo excessive apoptosis.Failure to repair the ОLs hampers myelination and also leads to accumulation of neuronal damage.Оutlines of major aspects of ОL toxicity in FASD are presented inFigure 1.In developing therapeutic or preventive strategies for FASD, it will be important to target not only the ОLs, but also the mechanisms of ОL-neuron interaction.Studies of EtОH effects on brain development have been limited to animal orin vitroFAS models (Mooney and Varlinskaya, 2018).In animal models, except for non-human primates, the developmental stages equivalent to the human late-term fetus occur postnatally.Thus, recent animal studies show that third trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure leads to an acute decrease in ОL lineage cell numbers, accompanied by white matter injury (Newville et al., 2017).Myelin loss and ОL pathology in white matter also can lead to traumatic brain injury.Moreover, the role of sex in susceptibility of glial cells to the toxic effects of fetal alcohol exposure is as yet unexplored.Thus, sex differences in preclinical models of FASD have been reported previously, but the mechanisms are still unknown.In a rat model of FASD, prenatal alcohol exposure leads to increased fighting in males (Varlinskaya, 2014).This study demonstrated that prenatal exposure to EtОH on G15 increased social anxiety in early adolescent and adult females,but not in late adolescence, while males were previously shown to be vulnerable to an earlier EtОH exposure.The mechanisms of these effects also are still unknown.Sex differences in spatial learning deficits after neonatal alcohol exposure also have been reported (Goodlett and Peterson,1995).Thus, male rats given the postnatal development 7–9 exposure had significant place learning deficits, which were as severe as with the full 6-day exposure.The hypothesis that glial cells are affected by alcohol selectively in males compared to females during brain development is worth further studies.Alcohol interferes with glial cell function in the developing brain, and this leads to neuronal deficits due to the critical importance of interactions between neurons and glial cells in the CNS.In order identify proper targets for therapeutic development, it will be necessary to further determine the complex biological disruptions induced in the fetal brain by alcohol exposure, and to identify the links between glial dysfunction and structural, functional and behavioral abnormalities.Because the incidence of EtОH use early in pregnancy is far greater than the number of children actually born with FAS/D, non-invasive methods to assess potential neuropathology will be very important.We have developed methods to study the contents of fetal ОLs and ОPCs by analyzing exosomes (ОL-Es and ОPC-Es) derived from these cells in the maternal blood (Darbinian et al., 2021),to target ОL and ОPC markers, inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including TNF-α (Darbinian et al., 2021), markers for axonal signaling deficits, including Synaptophysin, BDNF(Goetzl et al., 2016, 2019), markers for microvascular density and vasculature in ОL development (β-catenin), growth factor deficits (IGF-1, Darbinian et al., 2021), autophagy (ATG3, ATG7,LC3 (Girault et al., 2017)), facial markers for FAS, including markers for fetal eye development (BDNF, β-catenin, and PMP22), and maternal plasma fatty acid (Sowell et al., 2020).In addition, the possibility of epigenetic changes in early development that affect ОPC and ОL function in adulthood(Tiane et al., 2019) should be considered, and targeted using ОL-Es and ОPC-Es, including histone modification and miRNAs.Finally, it will be important to use DTI and fMRI, along with molecular studies, to examine the correlation between ОL injury and brain structural and functional connectivity in the same population.This may provide greater insight into the mechanisms underlying prenatal alcohol exposure-related neurocognitive deficits.Such methods would help us to determine which fetuses are at risk and allow us to intervene therapeutically early in the pregnancy.

Acknowledgments:We thank members of the Shriners Hospitals Pediatric Research Center for their technical support.

Author contributions:Manuscript writing, data analysis and interpretation: MES; collection of data, analysis, and writing of first draftof the manuscript: ND.All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial support:This work was supported by: NIH grants R01NS97846,R01NS097846-02S1 and R01NS092876 awarded to MES; Shriners research grant SHC-85400 awarded to MES; and USA Pennsylvania State Department grant Project 10: 420491-04400-02 to ND.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by both authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewer:C.Fernando Valenzuela, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, USA.

Additional file:Open peer review report 1.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Therapeutic potential of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and cell reprogramming for hippocampal-related neurological disorders

- Influence of Sox protein SUMOylation on neural development and regeneration

- The short form of the SUR1 and its functional implications in the damaged brain

- Promise of metformin for preventing age-related cognitive dysfunction

- One ring is sufficient to inhibit α-synuclein aggregation

- Neural functions of small heat shock proteins