Expression of nerve growth factor precursor, mature nerve growth factor and their receptors during cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury*☆

Guoqian He, Jian Guo, Jiachuan Duan, Wenming Xu, Ning Chen, Hongxia Li, Li He

1Department of Neurology, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China

2 National Chengdu Center for Safety Evaluation of Traditional Chinese Medicine, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China

3Joint Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine, Sichuan University-The Chinese University of Hongkong Joint Laboratory for Reproductive Medicine (SCU-CUHK), Institute of Women and Children’s Health, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China

lNTRODUCTlON

Nerve growth factor (NGF) has two forms,the NGF precursor (proNGF) and mature NGF. There is evidence that proNGF can be released by cells[1]. Recent studies have revealed that proNGF is post-translated,originating from two alternatively spliced transcripts, and following the removal of signal sequences in cells[2-3]. proNGF is then released from the cells and cleaved to form mature NGF after a complex extracellular proteolytic cascade[1-2]. Released proNGF has a high affinity for the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR), a tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member. The binding complex forms heterotrimers with sortilin to activate caspase and induce apoptosis,resulting in neurodegeneration[3-5]. proNGF is believed to exhibit neurotoxicity that contributes to neurodegeneration[6-7],whereas mature NGF promotes cell survival through its high binding affinity for TrkA.

However, in the uninjured central and peripheral nervous system of rodents and humans, proNGF is the major form of NGF expressed, while levels of mature NGF are typically very low or even undetectable[8-9].

Studies of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and central nervous system injury have confirmed that, in the central nervous system, proNGF expression can be detected for several days to weeks following injury[1,10-14]. Surprisingly, little conversion of proNGF to mature NGF has been observed in vivo, while proNGF/p75NTRhas been found to be involved in the pathophysiology of these diseases, by inducing apoptosis[1,10-14].

The current study used an immunohistochemical approach to examine the expression of proNGF, mature NGF, and receptors in the pathological process of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury.

RESULTS

Quantitative analysis of experimental animals

A total of 75 rats were randomly divided into a model group (n = 65) and a sham surgery group (n = 10). The model group underwent 2 hours of regional cerebral ischemia in the middle cerebral artery. The model group was further divided into five subgroups based on different reperfusion times (4 hours, and 1, 3, 7,and 14 days), with n = 10 for each subgroup. 15 animals were excluded from the model group because of unsuccessful surgery. A total of 60 rats were included in the final analysis.

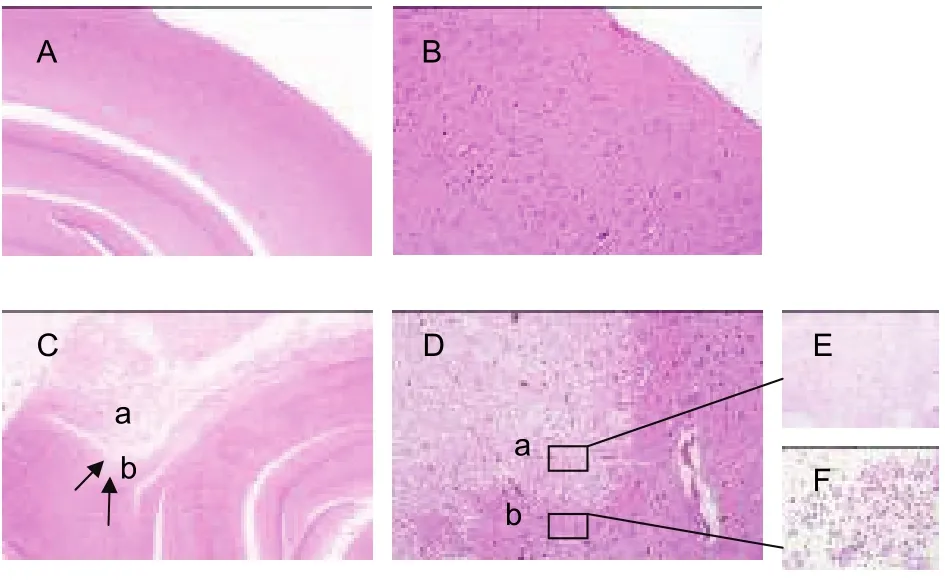

Pathological changes in the rat brain after ischemia and reperfusion

Following ischemia and reperfusion, the rats in the model group exhibited evident pathological changes in the ischemic cortices. The non-ischemic cortices in the model and sham surgery groups did not exhibit any pathological changes, with regular cortical structure,well-arranged, round, and fully-grown nerve cells,centrally-located blue-stained nuclei, absence of capillary expansion, and dense, red-stained interstitial tissue (Figures 1A, B). The infarct area (in which blood flow is supplied by the right middle cerebral artery)showed a marked reduction in the number of neurons,cell shrinkage, nuclear disintegration, and loose interstitial tissue (Figures 1C-E); the peri-infarct penumbra cortex displayed a disordered arrangement of nerve cells, pyknosis, eosinophilic change, loose interstitial tissue, and detectable glial cell histiocytosis,although a small number of intact nerve cells were still visible (Figure 1 F).

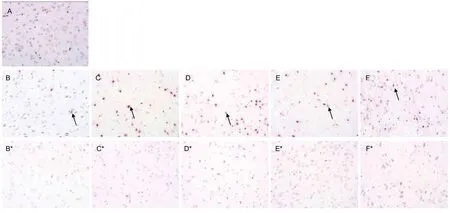

Cell apoptosis in the rat brain after ischemia and reperfusion

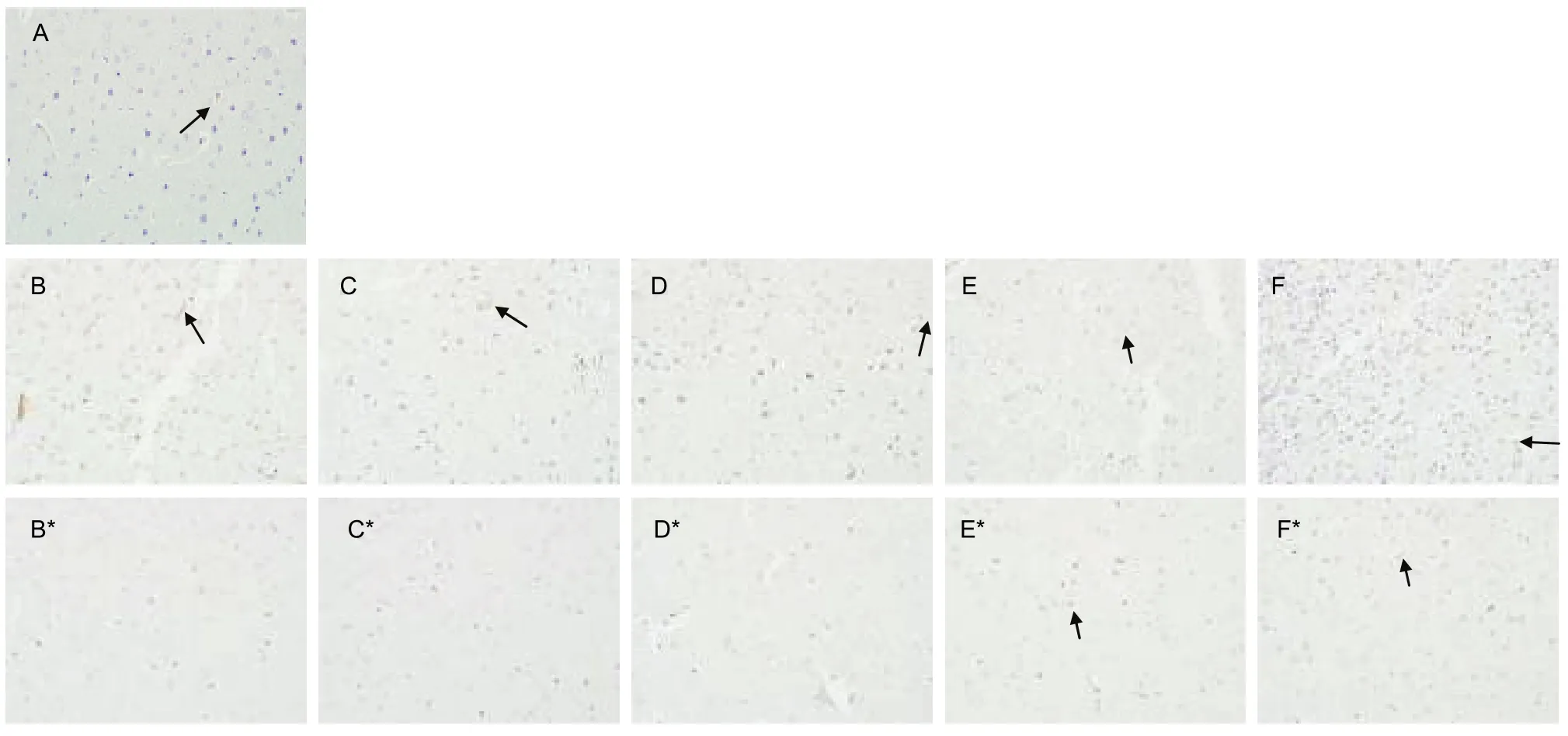

In the cortices of the sham surgery and model groups,TUNEL positive cells were stained red (Figure 2).

Compared with the sham surgery group, the percentage of TUNEL positive cells in ischemic cortex was slightly increased at 4 hours (t = 0.043, P < 0.05), reaching a peak value at 3 days (t = 0.001, P < 0.01; Figure 2D),and then decreased at 7 days (t = 0.005, P < 0.01), which was maintained at 14 days (t = 0.008, P < 0.01)compared with sham surgery group. In non-ischemic cortex, the percentage of TUNEL positive cells was not significantly different to the sham level (t = 0.09, P > 0.05;Figures 2, 3).

Figure 1 Histopathological changes in the rat brain after ischemia and reperfusion (hematoxylin-eosin staining). (A)(× 4) and (B) (× 20) are normal cortices. (C) (× 4) and (D)(× 20) are both focal cortical infarcts; arrows indicate the infarct formation. Arrow a is the infarct area, which shows markedly reduced neuron number, cell shrinkage, nuclear disintegration, and loose interstitial tissue; arrow b is the peri-infarct penumbra area, which shows disordered arrangement of nerve cells, pyknosis, eosinophilic change,loose interstitial tissue, detectable glial cell histiocytosis,and small amounts of intact nerve cells. (E) (×40) is the infarct area, which exhibits a markedly reduced neuron number, cell shrinkage, nuclear disintegration, and loose interstitial tissue. (F) (× 40) is the glial cell histiocytosis at the peri-infarct penumbra area.

Figure 2 Effects of ischemia and reperfusion on cell apoptosis in the rat brain (TUNEL staining, × 40). The TUNEL positive cells(arrows). (A) TUNEL positive cells in the sham surgery group. (B–F) TUNEL positive cells in the ischemic cortices; (B*-F*)TUNEL positive cells in the non-ischemic cortices from the model group with reperfusion for 4 hours and 1, 3, 7, and 14 days.

Expression of proNGF in cortices of rat brain after ischemia and reperfusion

In the cortices of the sham surgery and model groups,proNGF was expressed mainly in the cytoplasm and extracellular region. Compared with the sham surgery group, upon reperfusion after 2 hours of cortical ischemia,proNGF was significantly decreased in ischemic cortex,reaching the lowest value at 1 day, then gradually increased (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05). In non-ischemic cortex,proNGF was significantly increased at 1, 3 and 7 days(P < 0.01) (Figures 3, 4).

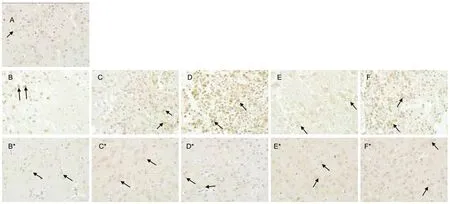

Expression of p75NTR in cortices of rat brain after ischemia and reperfusion

p75NTRwas expressed primarily in the cytoplasm.

Compared with the sham surgery group, upon reperfusion after 2 hours of cortical ischemia, p75NTRexhibited a gradual increase in ischemic cortex, reaching its peak value at 3 days (P < 0.01), and returned almost to the sham surgery group levels by 7 days (P > 0.05). In non-ischemic cortex, p75NTRlevels were slightly decreased at 4 hours, but began to slowly increase from 4 hours (Figures 3, 5).

Expression of mature NGF in cortices of rat brain after ischemia and reperfusion

Mature NGF was expressed in the extracellular region,but at a very low level. Compared with the sham surgery group, upon reperfusion after 2 hours of cortical ischemia, mature NGF was clearly increased in ischemic cortex. However, NGF levels returned to the sham level at 3 days, then increased at 7 days (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05). In non-ischemic cortex, mature NGF was slightly decreased, but increased and peaked at 7 days,then returned to the sham level at 14 days(Figures 3, 6).

Figure 5 Effects of ischemia and reperfusion on p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) in the rat brain (immunohistochemical staining, × 40). (A) Cortical immunoreactivity of p75NTR (brown) in the cytoplasm of cortical neuronal cells from the sham surgery group. Note the weak cytoplasmic staining for p75NTR in neurons. (B-F) Expression of p75NTR in ischemic cortices and (B*-F*)immunoreactivity of p75NTR in non-ischemic cortices from the model group with reperfusion for 4 hours and 1, 3, 7, and 14 days.The results revealed marked p75NTR immunoreactivity (brown) primarily in the cytoplasm of neurons (arrows).

Effects of ischemia and reperfusion on rat behaviors

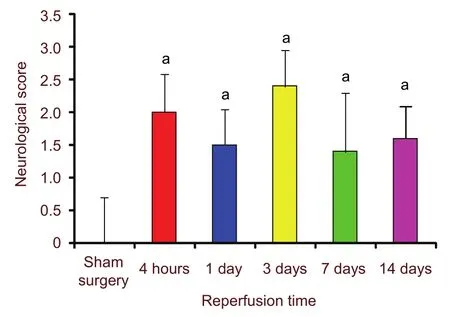

After ischemia and reperfusion, the animals in the model group exhibited different levels of focal neurological dysfunction, including left forelimb flexion and adduction during tail suspension, and circular motion to the left (or more severely, falling on their left side) when made to walk in a straight line. No neurological defects were observed in the sham surgery group. The neurological score of the model group was higher than that in the sham surgery group (Figure 7).

Figure 6 Effects of ischemia and reperfusion on mature nerve growth factor(NGF) in the rat brain (immunohistochemical staining, × 40). (A) Cortical immunoreactivity of mature NGF (brown) in the cytoplasm of cortical neuronal cells from sham surgery group. Note the weak cytoplasmic staining for mature NGF in neurons. (B–F) Expression of mature NGF in ischemic cortices and (B*–F*) immunoreactivity of mature NGF in non-ischemic cortices from the model group with reperfusion for 4 hours and 1, 3, 7, and 14 days. There was weak mature NGF immunoreactivity (brown) in the extracellular region of neurons (arrows).

Figure 7 Effects of ischemia and reperfusion on neurological score. aP < 0.01, vs. sham surgery group. 0:no neurological dysfunction; 1: failure to extend the left front paw during tail suspension; 2: circular motion to the left when walking; 3: difficulty in walking and falling to the left side; 4: failure to walk spontaneously and unconsciousness. Data were shown as mean ± SEM,compared with independent samples t-tests. n = 10 rats in each group.

DlSCUSSlON

Because a previous study reported that the sole function of proNGF is to release NGF[9], research on cerebral focal ischemia-reperfusion has typically not differentiated between proNGF and mature NGF. Using rat models of cerebral focal ischemia-reperfusion injury, the immunohistochemical results in the current study indicated that proNGF was expressed mainly in the extracellular region and cytoplasm of the cortices, while mature NGF expression was very low in the extracellular region, or even absent. These results indicate that during cortical ischemia-reperfusion, proNGF, but not mature NGF, may be the major form of NGF expressed. This notion is consistent with research on Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease[10-14]. On the basis of this evidence, we propose that the immune reaction of NGF observed in previous cerebral focal ischemia-reperfusion injury research may have also been caused by proNGF rather than mature NGF.

Compared with the sham surgery group, we found that proNGF and mature NGF showed the gradually decreased trend at 4 hours and 1 day in the ischemic area of the model group, partially because neurotrophic factors are produced by the target cells that neurons innervate (such as the cerebral cortex neurons), and ischemia can cause the loss of neural cells. This neuronal loss may cause a decrease in the expression of proNGF and mature NGF.

Our results indicated that proNGF was increased at 3 days, while mature NGF was decreased. There are several possible explanations for this result. First,research on Alzheimer’s disease has reported decreased transformation of proNGF to mature NGF and augmented degradation of mature NGF under pathological states[15-16]. The balance of cell death and survival is hypothesized to depend on the ratio of secreted proNGF and mature NGF[1]. Thus, whether the same mechanism exists in the pathological process of cortical ischemia-reperfusion injury requires further investigation. A recent study indicated that proNGF is converted to mature NGF through a complex proteolytic cascade (including PACE-4, PC-2, and plasmin) in the extracellular space, then mature NGF is rapidly degraded by matrix metalloproteinase-9[17]. Therefore, the expression of these proteases should be characterized during the transformation of proNGF to mature NGF in cortical ischemia-reperfusion injury to elucidate the transformation pathway, which is a potentially novel target in cortical ischemia-reperfusion injury therapy[18-19].

Second, mature NGF has a high binding affinity for TrkA,meaning that the expression of TrkA may influence the expression of mature NGF. Lee et al[20]reported that TrkA was induced in ischemic cortex, at days 1 and 3,and TrkA immunoreactivity was still present in the peri-infarct penumbra area. TrkA was not induced beginning at day 7 after ischemia in the ischemic cortex.

Third, compared with mature NGF, proNGF has been found to exhibit markedly lower in vivo binding affinity for receptor TrkA, and reduced neurotrophic activity[21-23].

The bioactivity of proNGF depends on the relative levels of receptors p75NTRand TrkA[23]; but whether proNGF also binds to TrkA in this pathology is unknown.

Therefore, determining the patterns of TrkA expression in the pathological process requires further investigation.

p75NTRis involved in the pathological process of cortical ischemia, and its expression is stimulated by ischemia[20].

Furthermore, p75NTRbelongs to the tumor necrosis factor superfamily and plays an important role in nerve cell death, primarily by mediating the JNK-p53-Bax apoptosis pathway[24]. In addition, our data revealed that p75NTRwas highly expressed in the cytoplasm of both ischemic and non-ischemic cortices, consistent with previous research involving p75NTRin cortical ischemia[25]. During cortical ischemia-reperfusion injury, in the ischemic area,the percentage of expression of TUNEL-positive cells and p75NTRdisplayed similar trends. Although cortical ischemia-reperfusion injury caused extensive nerve cell death in the ischemic area, the expression of proNGF and p75NTRdisplayed a similar trend at 1, 3 and 7 days.

In the non-ischemic cortex, proNGF and p75NTRdisplayed overall enhanced trend with increased reperfusion time, lasting for hours to days, then returned to the sham level at 14 days. However, p75NTRexpression was lower than in the sham surgery group and the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells exhibited no significant change. These findings indicate that proNGF/p75NTRmay be involved in the pathological process of cortical ischemia-reperfusion injury, consistent with previous research on proNGF/p75NTRin Alzheimer’s disease[10-14].

In conclusion, proNGF was found to be the major form of NGF expressed in the pathological process of cerebral focal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ischemia-reperfusion injury may influence the conversion of proNGF to mature NGF, and proNGF/p75NTRmay be involved in reperfusion injury after ischemia.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Design

A randomized, controlled, in vivo study.

Time and setting

The study was performed at the Department of Clinical Skill and Experimental Center, West China Hospital of Sichuan University in China from December 2009 to June 2010.

Materials

Animals

A total of 75 clean, healthy, male, Wistar rats, weighing 190-240 g were provided by the Animal Research Center of Sichuan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The rats were raised in quiet animal housing for 1 week, without exposure to strong light, at a temperature of 23°C and 55% humidity under a 12-hour day/night cycle. Animals were fed normal diets and allowed free access to water. The experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, formulated by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China[26].

Methods

Ischemia and reperfusion model establishment

Food was withheld (water access was maintained) for 12 hours before surgery. For the rats in the model group, an embolus was inserted into the right carotid artery to block the right middle cerebral artery using modified Zea-Longa’s thread method[27-28]. The rats were intraperitoneally anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate(0.35 mL/100 g). The necks of the supine rats were cut along the midline to expose the right common carotid artery, without stimulating the vagus nerve. The right common carotid artery, internal carotid artery, and external carotid artery were carefully isolated and maintained in a “Y” shape. The external carotid artery and common carotid artery were ligated, and a V-shaped incision was made on the common carotid artery at 1-2 mm from the carotid bifurcation. One end of a single nylon thread 50 mm in length and 0.2 mm in diameter was flame-heated to a ball shape; then the thread was slowly inserted into the internal carotid artery through the common carotid artery incision, and gradually moved up 18.5 ± 0.5 mm from the carotid bifurcation. This process was stopped when slight resistance was encountered,indicating that the thread had blocked the entrance of the middle cerebral artery. The nylon thread was fixed by ligating the internal carotid artery, and the incision was sutured. Body temperature was maintained at 37-37.5°C during the surgery.

To control for the side-effects of surgery, all procedures in the sham surgery group were the same as those in the model group, except that the middle cerebral artery was not blocked. The animals were individually raised in cages after surgery. Two hours after the right middle cerebral artery occlusion in the model group, the nylon thread was pulled out of the bifurcation to initiate reperfusion of the ischemic region (4 hours, and 1, 3, 7,and 14 days). Two hours of ischemia in animal middle cerebral artery occlusion caused evident cortical infarction[29].

Neurological evaluation

When the anesthetized animals regained consciousness,they were evaluated using the single-blinded Zea-Longa five-score method[28]before reperfusion and 24 hours before brain removal. Rats with scores of 1-3 were used in the subsequent experiments.

Tissue processing

On different reperfusion time points (4 hours, and 1, 3, 7,and 14 days), the animals were over-anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (0.8 mL/100 g), and the left ventricle was punctured with a blunt No. 16 puncture needle then reached the initial part of the aorta. The right heart was cut using ophthalmic scissors, and the blood was quickly rinsed with 100 mL saline; 10%formalin was used for heart perfusion. The heads were cut to remove the brain, which was fixed in 10%formalin for 24 hours. Coronal brain blocks were produced 2.5 mm from the frontal pole at 2-3 mm intervals through the middle cerebral artery territory[30-32],and were embedded in paraffin. Serial coronal sections of 4-μm thicknesses were cut with a LEICA RM2135 rotary microtome (Wetzlar, Germany).

Histopathological examinations

The brain sections were clarified with xylene and deparaffinized twice for 10 minutes. The sections were then rehydrated by ethanol gradient, stained with hematoxylin for 5 minutes, and washed with water for 5 minutes; the sections were then color separated with HCl and alcohol for 5-10 seconds, washed in water for 5 minutes, stained with eosin for 3-5 minutes, rehydrated with ethanol gradient, clarified with xylene, and mounted with neutral gum[33]. The sections were examined under light microscopy (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan).

TUNEL staining

We used the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche,11684809910), with the following protocol: each slide was placed in a plastic jar containing 200 mL 0.1 mol/L citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Apply 750 W (high) microwave irradiation for 1 minute. Each slide was cooled rapidly by immediately adding 80 mL double dist water (20-25°C). Slides were transferred into phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 20-25°C). Slides were immersed for 30 minutes at 15-25°C in Tris-HCl, 0.1 mol/L pH 7.5,containing 3% bovine serum albumin and 20% normal bovine serum. Slides were rinsed twice with PBS at 15-25°C. Excess fluid was allowed to drain off. 50 μL of TUNEL reaction mixture was added to the section,which was incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere in the dark. Slides were rinsed three times in PBS for 5 minutes each. Samples were then analyzed in a drop of PBS under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon eclipse Ti-u, Tokyo, Japan). Three fields were selected randomly and analyzed for each ischemia and non-ischemia cortex site of the middle cerebral artery territory. The percentages of TUNEL positive cells were then calculated.

Immunohistochemistry

The EnVision two-step method was used to analyze the expression of proNGF, mature NGF, and the receptor[34].

Brain sections were deparaffinized by baking at 65°C in an oven for 2-3 hours, washed in water, repaired by high pressure, washed in distilled water, and placed in triethanolamine-buffered saline. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% H2O2for 10 minutes. The sections were then washed in distilled water, kept in PBS for 10 minutes, and incubated in primary antibodies, including rabbit anti-rat proNGF antibody (1: 200; AB5583;Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA), rabbit anti-rat mature NGF antibody (1: 50; sc-548; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and rabbit anti-rat p75NTRantibody (1: 200; AB1554; Chemicon) at 4°C for 30 minutes. The sections were then washed in triethanolamine-buffered saline for 10 minutes, incubated in goat anti-rabbit antibodies (1: 10; Denmark and Carpinteria, CA, USA) at room temperature for 60 minutes, washed again in triethanolamine-buffered saline for 10 minutes, and followed by 3, 3'-diaminobenzidine with light control, rinsed in distilled water, double-stained, and covered.

Five fields were selected randomly and analyzed randomly for each cortex site. The absorbance was determined based on the positioning analysis results;integrated absorbance in positive cells was measured,and the mean density was calculated with the following formula: mean absorbance = log (absorbance detected in the cerebral cortex/absorbance of the background).

The absorbance of the background was the absorbance of the sections without the primary antibodies.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS,Chicage, IL, USA) and presented as mean ± SEM. Data from the ischemic and non-ischemic cortices at different reperfusion time points in the model and sham surgery groups were analyzed with independent samples t-tests.

A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions:Guoqian He and Jian Guo performed the experiment. Guoqian He organized and wrote the manuscript. Jiachuan Duan, Wenming Xu, Ning Chen, and Hongxia Li contributed to collect the data. Li He supervised and approved the final paper.

Funding:This work was supported by grants from National High Technology Program of China (863 Programs), No.2006AA02A117.

Ethical approval:All protocols were approved by the Animal Research Association at Sichuan University.

[1]Chen LW, Yung KK, Chan YS, et al. The proNGF-p75NTR-sortilin signalling complex as new target for the therapeutic treatment of Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2008;7(6):512-523.

[2]Rogers ML, Bailey S, Matusica D, et al. ProNGF mediates death of Natural Killer cells through activation of the p75NTR-sortilin complex. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;226(1-2):93-103.

[3]Bruno MA, Cuello AC. Activity-dependent release of precursor nerve growth factor, conversion to mature nerve growth factor,and its degradation by a protease cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(17):6735-6740.

[4]Frade JM, López-Sánchez N. A novel hypothesis for Alzheimer disease based on neuronal tetraploidy induced by p75 (NTR). Cell Cycle. 2010;9(10):1934-1941.

[5]Feng D, Kim T, Ozkan E, et al. Molecular and structural insight into proNGF engagement of p75NTR and sortilin. J Mol Biol. 2010;396(4):967-984.

[6]Hempstead BL. Commentary: Regulating proNGF action: multiple targets for therapeutic intervention. Neurotox Res. 2009;16(3):255-260.

[7]Feng D, Kim T, Ozkan E, et al. Molecular and structural insight into proNGF engagement of p75NTR and sortilin. J Mol Biol.2010;396(4):967-984.

[8]Fahnestock M, Michalski B, Xu B, et al. The precursor pro-nerve growth factor is the predominant form of nerve growth factor in brain and is increased in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Cell Neurosci.2001;18(2):210-220.

[9]Lee R, Kermani P, Teng KK, et al. Regulation of cell survival by secreted proneurotrophins. Science. 2001;294(5548):1945-1948.

[10]Al-Shawi R, Hafner A, Olsen J, et al. Neurotoxic and neurotrophic roles of proNGF and the receptor sortilin in the adult and ageing nervous system. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27(8):2103-2114.

[11]Beattie MS, Harrington AW, Lee R, et al. ProNGF induces p75-mediated death of oligodendrocytes following spinal cord injury. Neuron. 2002;36(3):375-386.

[12]Harrington AW, Leiner B, Blechschmitt C, et al. Secreted proNGF is a pathophysiological death-inducing ligand after adult CNS injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6226-6230.

[13]Stoica G, Lungu G, Kim HT, et al. Up-regulation of pro-nerve growth factor, neurotrophin receptor p75, and sortilin is associated with retrovirus-induced spongiform encephalomyelopathy. Brain Res. 2008;1208:204-216.

[14]Wang YJ, Valadares D, Sun Y, et al. Effects of proNGF on neuronal viability, neurite growth and amyloid-beta metabolism.Neurotox Res. 2010;17(3):257-267.

[15]Cuello AC, Bruno MA. The failure in NGF maturation and its increased degradation as the probable cause for the vulnerability of cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Res.2007;32(6):1041-1045.

[16]Cuello AC, Bruno MA, Allard S, et al. Cholinergic involvement in Alzheimer's disease. A link with NGF maturation and degradation.J Mol Neurosci. 2010;40(1-2):230-235.

[17]Lim KC, Tyler CM, Lim ST, et al. Proteolytic processing of proNGF is necessary for mature NGF regulated secretion from neurons.Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361(3):599-604.

[18]Yune TY, Lee JY, Jung GY, et al. Minocycline alleviates death of oligodendrocytes by inhibiting pro-nerve growth factor production in microglia after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27(29):7751-7761.

[19]Zhang J, Brodie C, Li Y, et al. Bone marrow stromal cell therapy reduces proNGF and p75 expression in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;279(1-2):30-38.

[20]Lee TH, Kato H, Chen ST, et al. Expression of nerve growth factor and trkA after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke.1998;29(8):1687-1697.

[21]Buttigieg H, Kawaja MD, Fahnestock M. Neurotrophic activity of proNGF in vivo. Exp Neurol. 2007;204(2):832-835.

[22]Fahnestock M, Yu G, Michalski B, et al. The nerve growth factor precursor proNGF exhibits neurotrophic activity but is less active than mature nerve growth factor. J Neurochem. 2004;89(3):581-592.

[23]Masoudi R, Ioannou MS, Coughlin MD, et al. Biological activity of nerve growth factor precursor is dependent upon relative levels of its receptors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(27):18424-18433.

[24]Niewiadomska G, Mietelska-Porowska A, Mazurkiewicz M. The cholinergic system, nerve growth factor and the cytoskeleton.Behav Brain Res. 2011;221(2):515-526.

[25]Andsberg G, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Upregulation of p75 neurotrophin receptor after stroke in mice does not contribute to differential vulnerability of striatal neurons. Exp Neurol. 2001;169(2):351-363.

[26]The Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 2006-09-30.

[27]Iwashita A, Tojo N, Matsuura S, et al. A novel and potent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor, FR247304 (5-chloro-2-[3-(4-phenyl-3,6-dihydro-1(2H)-pyridinyl)propyl]-4(3H)-quinazolin one), attenuates neuronal damage in in vitro and in vivo models of cerebral ischemia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(2):425-436.

[28]Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, et al. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20(1):84-91.

[29]Zhan X, Kim C, Sharp FR. Very brief focal ischemia simulating transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) can injure brain and induce Hsp70 protein. Brain Res. 2008;1234:183-497.

[30]Xing Y, Hua Y, Keep RF, et al. Effects of deferoxamine on brain injury after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats with hyperglycemia. Brain Res. 2009;1291:113-121.

[31]Popp A, Jaenisch N, Witte OW, et al. Identification of ischemic regions in a rat model of stroke. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):e4764.

[32]Dzialowski I, Klotz E, Goericke S, et al. Ischemic brain tissue water content: CT monitoring during middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion in rats. Radiology. 2007;243(3):720-726.

[33]Hashimoto M, Zhao L, Nowak TS Jr. Temporal thresholds for infarction and hypothermic protection in Long-Evans rats: factors affecting apparent 'reperfusion injury' after transient focal ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39(2):421-426.

[34]K?mmerer U, Kapp M, Gassel AM, et al. A new rapid immunohistochemical staining technique using the EnVision antibody complex. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49(5):623-630.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Meta-analysis of transcranial magnetic stimulation to treat post-stroke dysfunction○

- Correlation of E-selectin gene polymorphisms with risk of ischemic stroke A meta-analysis☆

- Penehyclidine hydrochloride attenuates cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage☆

- Non-acute effects of different doses of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on spatial memory in the Morris water maze in Sprague-Dawley male rats**☆●

- Hypothermic intervention for 3 hours inhibits apoptosis in neonatal rats with hypoxic-ischemic brain damage★

- Role of the nerve growth factor precursor-neurotrophin receptor p75 and sortilin pathway on apoptosis in the brain of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage*☆