Meta-analysis of transcranial magnetic stimulation to treat post-stroke dysfunction○

Yang Tian, Lianguo Kang, Hongying Wang, Zhenyi Liu

1Department of Rehabilitative Medicine, Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences of Jilin Province, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China

2Department of Surgery, Creighton University, Omaha 68131, Nebraska, USA

3Department of Medical Laboratory, First Clinical Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China

INTRODUCTION

Since the end of the 20thcentury,transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)techniques have been used in basic neuroscience research, clinical studies and disease diagnosis. TMS studies have become an important area of neuroscience research[1]. In TMS, time-varying magnetic fields induce induction current from the cerebral cortex, altering the action potentials of cortical nerve cells, which influences brain metabolism and neuroelectric activity. TMS was initially developed to overcome the disadvantages of electric stimulation. TMS does not involve pain, is minimally invasive,and can be performed safely. In addition,TMS is simple to operate, and provides a novel option for clinical and experimental stroke research[2-3].

Studies of TMS have mainly focused on its application in brain science and clinical medicine based on magnetic stimulation theory. As a novel electrophysiological technique, TMS has the advantages of its extensive range of applications, safety and minimal adverse effects, as well as the simplicity of its operation. With the development of biomedical engineering and computer techniques and increased understanding of the pathological mechanisms of stroke, TMS has an increasingly great potential for treating stroke[4]. The current study summarized clinical randomized, controlled experiments for treating post-stroke dysfunction with TMS. We sought to evaluate the efficacy of TMS using large samples and provide objective evidence for its clinical use.

DATA AND METHODS

Literature retrieval

The VIP and PubMed databases were searched, to find articles published between January 1989 and December 2010 using the key words “transcranial magnetic stimulation” and “stroke”. A total of 16 articles were identified in the VIP database, while 713 were identified in the PubMed database. These articles were further screened to find studies involving randomized clinical trials (RCT). Following this screening process, 1 article from the VIP database and 60 articles from PubMed database were included in the final analysis. The fill inclusion procedures are listed in the supplementary information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Study type: Published RCTs examining the use of TMS to treat post-stroke dysfunction, with detailed data,including mean age of onset, proportion of gender, onset site, and imaging of pathological changes, were included.

We included clinical case analyses and case reports involving at least two cases to minimize the random variation introduced by including single cases. We conducted our selection regardless of the countries or regions in which the studies were conducted. All articles were published in either English or Chinese.

Study subjects: The subjects were stroke patients with detailed data including mean age of onset, gender ratio,etc.

Intervention study: The treatment group patients received conventional rehabilitative training and TMS treatment, while the control group was only treated with conventional rehabilitative training.

Outcome measures and judgment criteria: The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to detect cognitive function[5]; depression was evaluated using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression(HAMD)[6]; neurological function was assessed using the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)[7]; line bisection (LB) and line cancellation (LC) tests were used to evaluate hemispatial neglect in patients[8].

Exclusion criteria

Studies that were not designed in accordance with the requirements of RCTs, or using different diagnostic standards or insufficient samples, were excluded.

Studies for which only abstracts could be found, and studies that were repetitively published, lacked a control group, or lacked intact data were also excluded. In addition, reviews, comments and reports were not included.

Quality evaluation and data extraction

The quality of studies was assessed by two authors,Yang Tian and Lianguo Kang, who screened clinical trials according to whether they used randomized methods, blind methods, or lost subjects to follow-up.

Data were checked, and missing data were supplemented by contacting the authors of the studies in question. The results obtained by two authors were verified by the other authors. Whenever necessary, a third researcher was also consulted. The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated according to the standards of the Cochrane Reviewer’s Handbook system (www.cochrane.org)[9].

Evaluation items included key indices for evaluating the external and internal validity of RCTs: randomized methods; concealed allocation; blind methods; loss of follow-up or withdrawal (whether intention to treat was used in cases that were lost of follow-up or when subjects had withdrawn); and comparability of baseline data. Concealed allocation was classified into four categories: A (complete concealing), B (unclear concealing), C (insufficient concealing), and D (no concealing). All other studies were divided into A (Yes),B (unclear), and C (No) categories.

For example, if all evaluation items were classified as grade A (i.e. the bias degree was low, indicating a minimal possibility of bias), the quality of the study was considered grade A. If one or more items was classified as grade B (i.e. the possibility of bias was medium), the quality of the study was considered grade B. If one or more items was classified as grade C (i.e. the possibility of bias was high), the quality of the study was considered grade C.

Statistical analysis

Collected data were analyzed using Revman4.2.2 software, provided by Cochrane (www.cochrane.org).

This process involved heterogeneity testing,meta-analysis, funnel plot analysis, and sensitivity analysis. A fixed-effects model was used in meta-analysis when P > 0.05 in the heterogeneity test,and a random-effects model was used when P ≤ 0.05 in the heterogeneity test. Subgroup analysis was performed according to items that may induce clinical heterogeneity to identify the source of heterogeneity.

When quantitative results were positive in the relative risk (RR) and risk difference (RD) analyses, the number needed to treat was calculated manually. Measurement data were analyzed using weighted mean differences(WMD), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

RESULTS

Characteristics of included studies

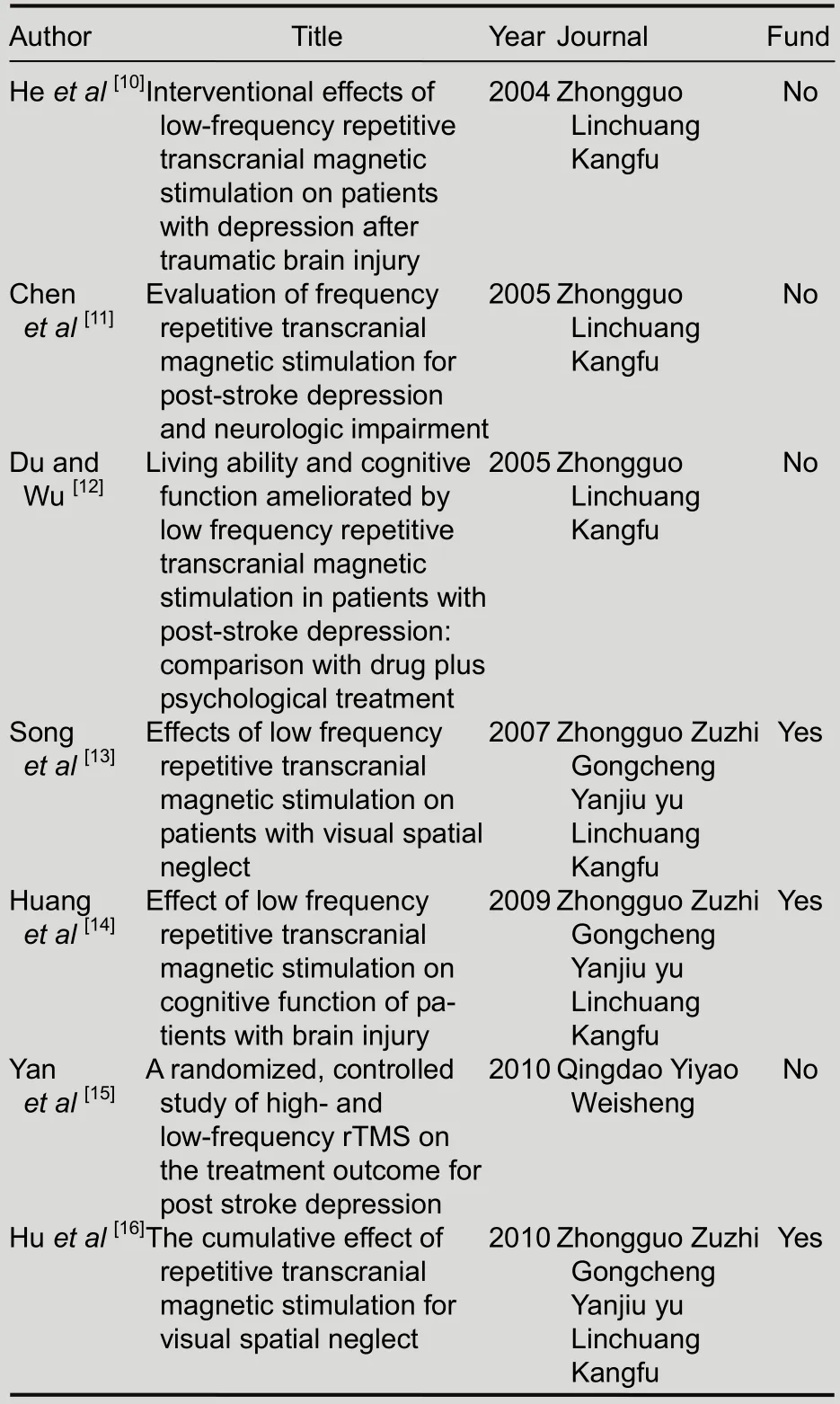

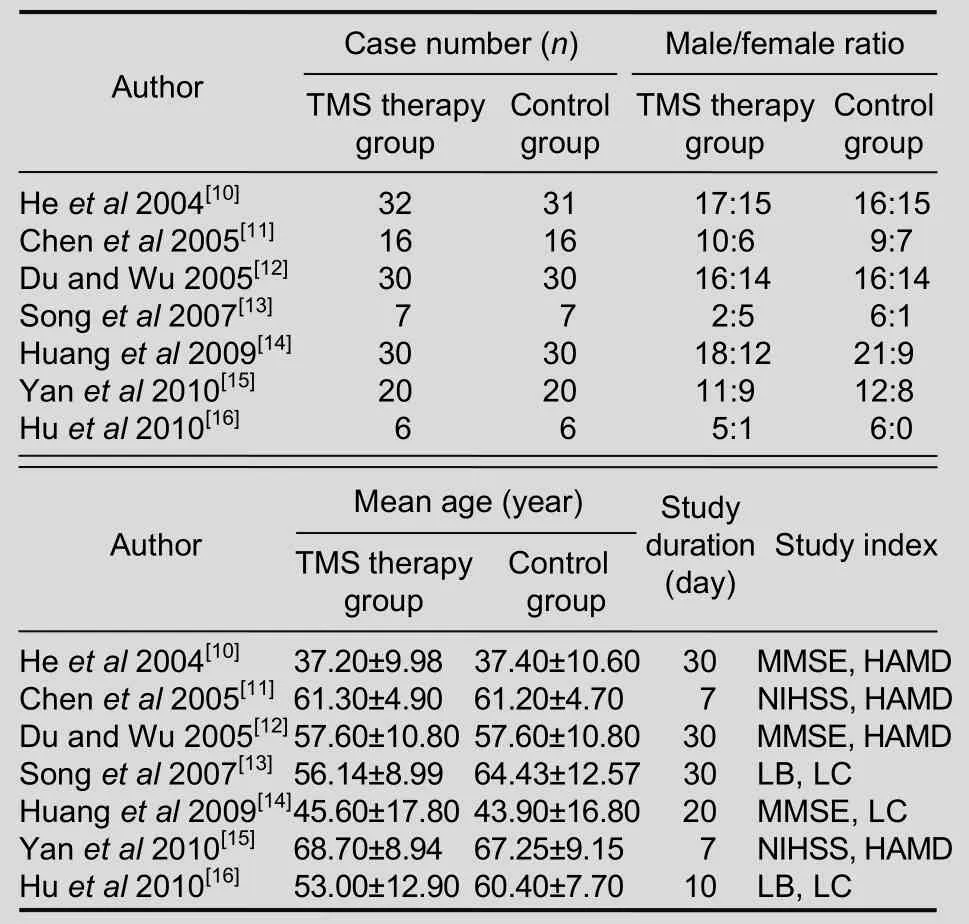

Following the analysis, a total of seven full-text articles[10-16]were finally included, published between 2004 and 2010. Animal experiments, case reports,reviews and discussions were excluded. The publication and characteristics of the included articles are shown in Tables 1, 2. Of the seven articles, patients were only followed up in three[13-14,16].

Table 1 Publication of included articles

Table 2 Basic characteristics of included articles

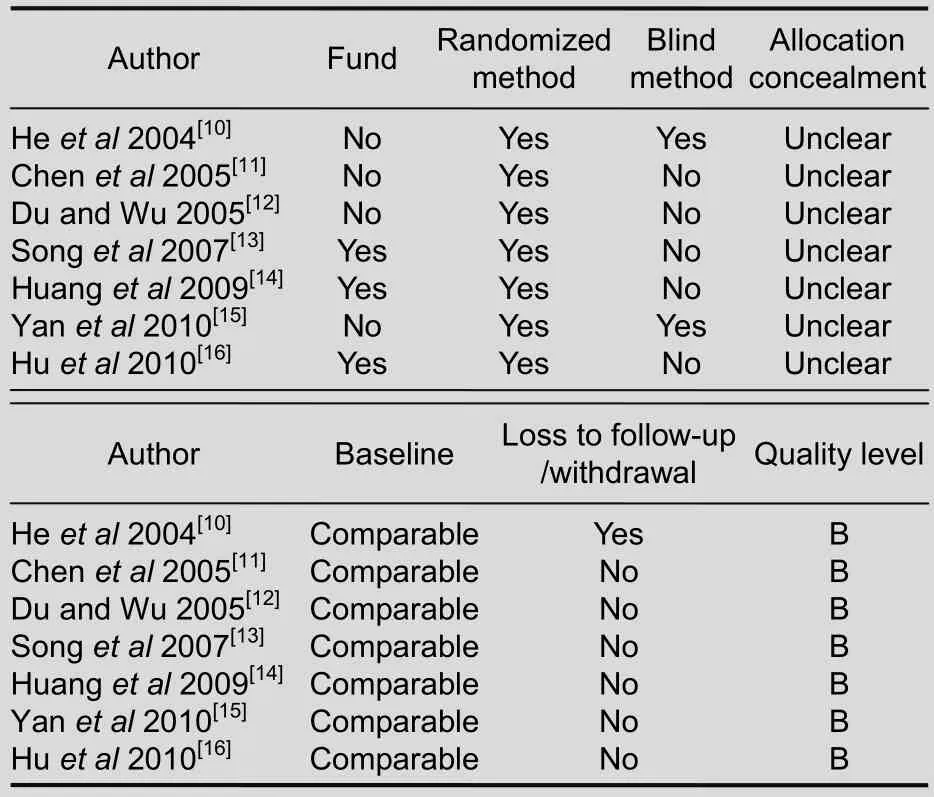

Quality evaluation of included studies

According to Cochrane quality evaluation standards for RCTs, the baseline of the seven articles was similar.

However, the random allocation methods were not introduced in detail. Except for references 6 and 11, all articles were free of blind methods or concealed allocation.The quality of articles was all grade B (Table 3).

Table 3 Quality evaluation of included articles

Meta-analysis results of study indices

According to determined indices, the studies were assigned to five groups. The scores of MMSE, HAMD,NIHSS and results of LB and LC were compared among groups (Figures 1-5).

MMSE scores of patients following TMS treatment

Three studies compared MMSE scores, involving 92 patients in the treatment group and 91 in the control group. The scores were significantly higher in treatment group compared with control group [WMD = 3.96, 95%CI (2.44, 5.49), P = 0.08; Figure 1].

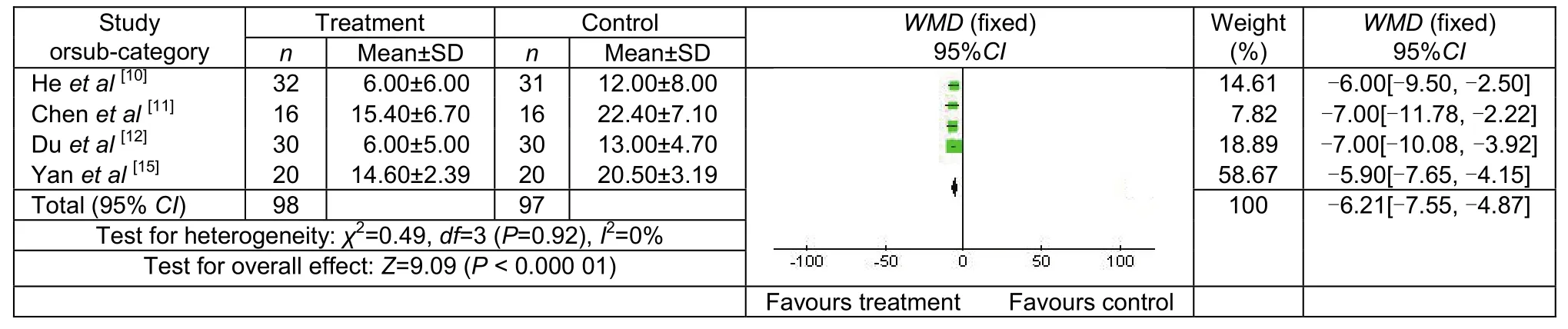

HAMD scores of patients following TMS treatment

Four studies compared HAMD scores, involving 94 patients in treatment group and 97 in control group. The scores were significantly lower in the treatment group compared with the control group [WMD = -6.21, 95% CI(-7.55, -4.87), P = 0.92; Figure 2].

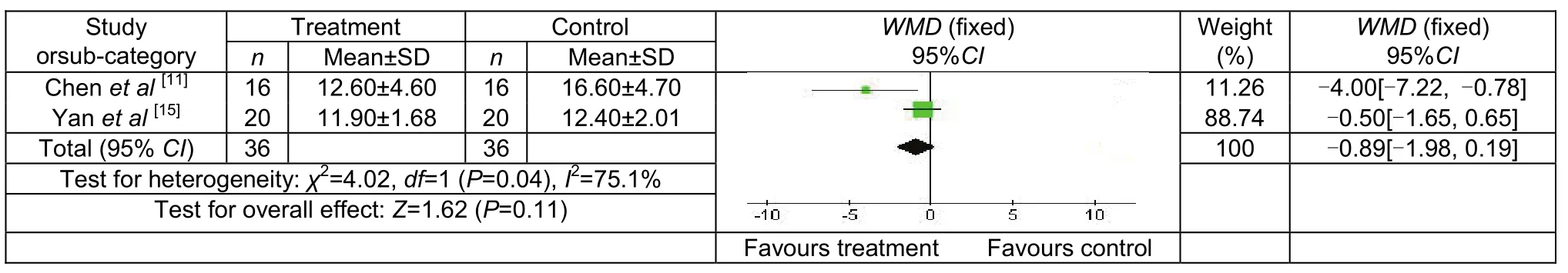

NIHSS scores of patients following TMS treatment

Two studies compared NIHSS scores, involving 26 patients in the treatment group and 26 in the control group. The scores were significantly lower in the treatment group compared with the control group[WMD = -0.89, 95% CI (-1.98, 0.19), P = 0.04;Figure 3].

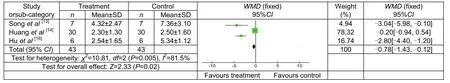

LB results of patients following TMS treatment

Three studies compared LB results of patients,involving 43 patients in the treatment group and 43 in the control group. The results were significantly better in treatment group compared with the control group[WMD = -0.78, 95% CI (-1.43, -0.12), P = 0.005;Figure 4].

Figure 1 Mini-mental State Examination scores of control and treatment groups following transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment

Figure 2 Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores of control and treatment groups following transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment.

Figure 3 National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores of control and treatment groups following transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment.

Figure 4 Line bisection results of control and treatment groups following transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment.

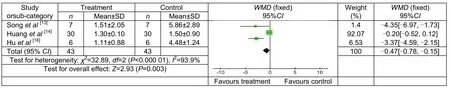

Figure 5 Line cancellation results of control and treatment groups following transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment.

LC results of patients following TMS treatment

Three studies compared LB performance of patients,involving 43 patients in treatment group and 43 in control group. The results were significantly superior in treatment group compared with control group [WMD =-0.47, 95%CI (-0.78, -0.15), P < 0.000 01; Figure 5].

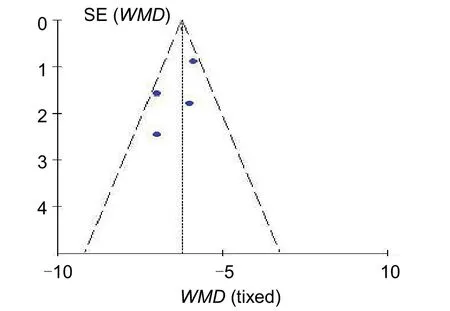

Publication bias

A funnel plot was drawn to analyze potential publication bias. The funnel plot of four articles involving HAMD scores following TMS treatment showed no evident bias(Figure 6).

Figure 6 Funnel plot of Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores following transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment. WMD: Weighted mean difference.

Sensitivity analysis

The analysis results after eliminating articles with unknown diagnostic standards and statistical methods were identical to those before eliminating.

DISCUSSION

Summary of study quality

To prevent the omission of relevant articles, we utilized an extensive retrieval procedure, in combination with inclusion and exclusion criteria to control bias and ensure the results were reliable. The sample size of this study was relatively small. We included only seven studies,involving a total of 281 patients. As such the statistical power of many of these studies may not be sufficient to draw firm conclusions. In addition, the quality of the included studies was low, and the evaluation indices differed between studies, meaning that comprehensive analysis was not possible.

Therapeutic effects of TMS

TMS can serve as a therapy, and as an evaluation method. In the current analysis, a total of 60 articles were found in the PubMed database. After screening titles and abstracts, related studies were examined, and the abstracts were read. After a 2-week period of TMS treatment for patients with post-stroke neuropathic pain,the pain was relieved for a long period of time, with no adverse effects[17]. Therefore, TMS is an effective and safe adjuvant treatment for post-stroke dysfunction[18-22].

Urban et al[23]treated six dysarthric patients with TMS and evaluated sensory function and somatosensoryevoked potentials. The results of our analysis indicated that TMS exerted favorable effects on post-stroke dysfunction, such as improving cognitive function and the activities of daily living. TMS treatment produces a rapidly fluctuating magnetic field, inducing a transient current in an insulated coil by rapid discharge, which excites the white matter in the cerebral cortex[24],triggering action potentials and inducing postsynaptic neurons to release neurotransmitter[18]. There is increasing evidence that central nervous systems are capable of structural and functional rebuilding[25].

Surviving neurons can reconnect with target nerve tissues through axonal lateral branch sprouting to replace axons that have lost functionality[26-27]. In addition,these cells can form new nervous pathways with surrounding intact neurons or by compensation of low-level center[28]. Studies of TMS have mainly focused on its applications in brain science and clinical medicine based on magnetic stimulation theory[29-32]. As a promising treatment tool[33-38], TMS techniques could be rapidly developed in future.

Although TMS has some advantages compared with medication and can be used to improve clinical symptoms of stroke patients in a short period of time,some questions remain. For example, the optimal TMS stimulation parameters are currently unclear. In addition,the effects of combined stimulation of the dorsal cortex of the left prefrontal lobe with high-frequency current,and stimulation of the dorsal cortex of the right prefrontal lobe with low-frequency current compared with stimulation using a single frequency are currently unclear, as are the long-term effects of TMS, and the differences in optimal parameters for different populations.

Study limitations

TMS is a newly developed therapeutic technique in China. The seven articles included in this study involved a total of 281 patients, providing a relatively small sample size. Moreover, the conditions of patients that were not described in detail could not be included in the analysis.

In addition, our results revealed that randomized methods, concealed allocation, and blind methods were not appropriately used, resulting in a high likelihood of publication bias. The quality of included articles was low,evaluation indices varied between studies, and it was difficult to perform combined analysis.

Author contributions:Yang Tian composed and designed this article, analyzed the related data, wrote the article, and performed statistical analyses and he was the guarantor.Lianguo Kang checked and revised this article. The results were verified by Hongying Wang and Zhenyi Liu.

Conflicts of interest:None declared.

Ethical approval:None declared.

Supplementary information:Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, by visiting www.nrronline.org, and entering Vol. 6, No. 22, 2011 after selecting the “NRR Current Issue” button on the page.

[1]Wang XM, Xie JP, Zhou SY, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and its clinical application. Guowai Yixue: Wuli Yixue yu Kangfu Xue Fence. 2004;24(1):43-46.

[2]Wang W. Application of rTMS in clinical mental and neurological.Jingshen Jibing yu Shenjing Weisheng. 2007;7(3):233-236.

[3]Lv H, Tang JT. Progress of transcranial magnetic stimulation.Zhongguo Yiliao Qixie Xinxi. 2006;12(5):28-32.

[4]Wang XM, Zhou SS. Application of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and therapeutic. Jingshen Jibing yu Shenjing Weisheng. 2003;3(5):402-403.

[5]Zhang MY. Psychiatric Rating Scale Manual. 2. Changsha: Hunan Science Press.1998

[6]Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Tateno A, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as treatment of poststroke depression:a preliminary study. Biol Psychiatry. 2004,55(4):398-405.

[7]U.S. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)Introduction. Clinical Meta. 2009, 08-016.

[8]Lee BH, Kang SJ, Park JM, et al. The Character line Bisection Task a new test for hemispatial neglect. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(12):1715-1724.

[9]Tian Y, Kang LG, Wang HY, et al. Biofeedback therapy improves motor function following stroke: meta-analysis of 14 articles from Chinese Medica Institutions. Neural Regen Res. 2010;5(7):538-544.

[10]He CS, Yu Q, Yang DJ, et al. Interventional efects of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on patients with depression after traumatic brain injury. Zhongguo Linchuang Kangfu. 2004;8(28):6044-6045.

[11]Chen YP, Mei WV, Sun SG, et al. Evaluation of frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for post-stroke depression and neurologic impairment. Zhongguo Linchuang Kangfu. 2005;9(20):18-19.

[12]Du DQ, Wu YB. Living ability and cognitive function ameliorated by low frequency repetitive transcranial agnetic stimulation in patients with post-stroke depression:comparison with drug plus psychelagical treatment. Zhongguo Linchuang Kangfu. 2005;9(16):22-23.

[13]Song WQ, Li YZ, Du BQ, et al. Effects of low frequency repetitive transcr anial magnetic stimulation on patients with visual spatial neglect. Zhongguo Kangfu Yixue Zazhi. 2007;22(6):483-486.

[14]Huang JK, Mai RK, Chen SJ. Effect of low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cognitive function of patients with brain lnjury. Zhongguo Kangfu Yixue Zazhi. 2009;24(4):231-232.

[15]Yan TT, He LM, Gu ZT. A randomized, controlled study of highand low-frequency RTMS on the treatment outcome for post stroke depression. Qingdao Yiyao Weisheng. 2010;42(2):81-85.

[16]Hu J, Du BQ, Yue HY, et al. The cumulative efect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for visual spatial neglect.Zhongguo Kangfu Yixue Zazhi. 2010;25(4):311-314.

[17]Khedr EM, Kotb H, Kamel NF, et al. Longlasting antalgic effects of daily sessions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in central and peripheral neuropathic pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(6):833-838.

[18]Huerta PT, Volpe BT. Transcranial magnetic stimulation, synaptic plasticity and network oscillations. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2009;2(6):7.

[19]Kapogiannis D, Wassermann EM. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical pharmacology. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2008;8(4):234-240.

[20]Schlaug G, Renga V, Nair D. Transcranial direct current stimulation in stroke recovery. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(12):1571-1576.

[21]Bolognini N, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F. Using non-invasive brain stimulation to augment motor training-induced plasticity. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2009;17(6):8.

[22]Malcolm MP, Triggs WJ, Light KE, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as an adjunct to constraint-induced therapy:an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(9):707-715.

[23]Urban PP, Wicht S, Hopf HC, et al. Isolated dysarthria due to extracerebellar lacunar stroke: a central monoparesis of the tongue. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66(4):495-501.

[24]Cowey A. The Ferrier Lecture 2004 what can transcranial magnetic stimulation tell us about how the brain works? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1458):1185-1205.

[25]Zhou SF. Brain plasticity after stroke research and the progress of recovery. Zhonghua Wuli Yixue yu Kangfu Zazhi. 2002;24(7):437-439.

[26]Vogel G. New brain cells promopt Dew theory of depression.Science. 2000;290(13):257-258.

[27]Jiang CY, Hu YS. Rehabilitative training to promote functional recovery after cerebral infarction progress of basic research on the mechanism. Zhonghua Wuli Yixue yu Kangfu Zazhi. 2002;27(7):443-445.

[28]Wang XQ, Li J, Li TS. The impact of early rehabilitation on stroke patients with upper extremity function. Qilu Yixue Zazhi. 2002;17(4):331.

[29]Liu HY, Yan TB. Progress in the evaluation of stroke by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Zhongguo Kangfu Yixue Zazhi.2010;25(2):182-185.

[30]Griskova I, Hoppner J, Ruksenas O, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: the method and application. Medicina(Kaunas). 2006;42(10):798-804.

[31]Wittenberg GF, Bastings EP, Fowlkes AM, et al. Dynamiccourse of intracortical TMS paired-pulse resents during recovery of motor function after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2007;21(6):568-573.

[32]Cicinelli P, Marconi B, Zaceagnini M, et al. Imageryinducedcortical excitability changes in stroke:a transcranial magneticstimulation study. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(2):247-253.

[33]Stinear CM, Fleming MK, Barber PA, et al. Lateralization of motor imagery following stroke. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118(8):1794-1801.

[34]Liepert J. Motor cortex excitability in stroke before and after constraint-induced movement therapy. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2006;19(1):41-47.

[35]Mark VW, Taub E, Moms DM. Neuroplasticity and constraintinduced movement therapy. Eura Medieuphys. 2006;42(3):269-284.

[36]Summers JJ, Kagerer FA, Garry MI, et al. Bilateral and unilateral movement training on upper limb function in chronicstroke patients: a TMS study. J Neurol Sci. 2007;252(1):76-82.

[37]Misawa S, Kuwabara S, Matsuda S, et al. The ipsilateralcorticospinal tract is activated after hemiparetic stroke.Eur J Neurol. 2008;l5(7):706-711.

[38]Liu HY, Yan TB, Liu F, et al. Functional electrical stimulation on stroke patients and exercise our powers on the physical sense of the impact of evoked potentials. Zhongguo Kangfu Yixue Zazhi.2009;24(9):793-796.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Correlation of E-selectin gene polymorphisms with risk of ischemic stroke A meta-analysis☆

- Penehyclidine hydrochloride attenuates cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage☆

- Non-acute effects of different doses of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on spatial memory in the Morris water maze in Sprague-Dawley male rats**☆●

- Hypothermic intervention for 3 hours inhibits apoptosis in neonatal rats with hypoxic-ischemic brain damage★

- Expression of nerve growth factor precursor, mature nerve growth factor and their receptors during cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury*☆

- Role of the nerve growth factor precursor-neurotrophin receptor p75 and sortilin pathway on apoptosis in the brain of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage*☆