Risk factors and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with low birth weight in Northern Tanzania:A registry-based retrospective cohort study

Modesta MitaoRune Nathaniel Philemon,,,Joseph ObureObure, Blandina Theophil Mmbaga,SiaEmmanuel Msuya,, Michael J MahandeKilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, Kilimanjaro, TanzaniaDepartment of Paediatrics, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Kilimanjaro, TanzaniaDepartment of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, Kilimanjaro, TanzaniaDepartment of Community Health, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Kilimanjaro, TanzaniaDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, Moshi, Tanzania

ABSTRACT

Objective:To determine the risk factors for low birth weight and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with low birth weight in Northern Tanzania. Methods:A retrospective cohort study was designed using maternally linked data from Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) medical birth registry. A total of 37 799 singleton births delivered from 2000 to 2013 were analyzed. Multiple births, stillbirth and infants with birth defects were excluded. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 16.0. Chi-square was used to compare difference in proportions between groups. The relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals(CIs) for the factors and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with LBW were estimated in a multivariate logistic regression models. Results:The incidence of low birth weight was 10.6%. Multivariate logistic regression showed that pre-eclampsia (RR 3.9; 95% CI 3.6-4.2), eclampsia (RR 5.4; 95% CI 4.1-6.9), chronic hypertension (RR 2.8; 95% CI 2.1-3.8), maternal anaemia (RR 1.7; 95% CI 1.4-2.2), HIV status (RR 0.8; 95% CI 0.7-0.8), smoking during pregnancy (RR 1.9; 95% CI 1.0-3.5), caesarean section delivery (RR 1.4; 95% CI 1.3-1.5), placental abruption (RR 3.7; 95% CI 1.3-4.7), placenta previa (RR 6.6; 95% CI 4.8-9.3), PROM (RR 2.5; 95% CI 1.9-3.3), maternal underweight (RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.2-1.6), and obesity (RR 1.2; 95% CI 1.1-1.4) and female gender of baby were associated with delivery of low birth weight infants. On the other hand, LBW infants had increased risk of neonatal jaundice (RR 2.7; 95% CI 1.2-6.1), being delivered preterm (RR 2.0; 95% CI 1.8-2.3), Apgar score (<7) at fifth minute (RR 5.5; 95% CI 4.5-6.6) and early neonatal death (RR 3.5; 95% CI 2.6-4.6). Conclusions:Low birth weight is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Early identification of risk factors for low birth weight through prenatal surveillance of high risk pregnant women may help to prevent these adverse perinatal outcomes.

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 3 July 2015

Received in revised form 6 October 2015

Accepted 15 October 2015

Available online 1 January 2016

?

Risk factors and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with low birth weight in Northern Tanzania:A registry-based retrospective cohort study

Modesta Mitao1Rune Nathaniel Philemon1,2,3,Joseph Obure4,4Obure4, Blandina Theophil Mmbaga1,2SiaEmmanuel Msuya1,3,4, Michael J Mahande3*

1Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

2Department of Paediatrics, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

3Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

4Department of Community Health, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

5Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, Moshi, Tanzania

ABSTRACT

Objective:To determine the risk factors for low birth weight and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with low birth weight in Northern Tanzania. Methods:A retrospective cohort study was designed using maternally linked data from Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) medical birth registry. A total of 37 799 singleton births delivered from 2000 to 2013 were analyzed. Multiple births, stillbirth and infants with birth defects were excluded. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 16.0. Chi-square was used to compare difference in proportions between groups. The relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals(CIs) for the factors and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with LBW were estimated in a multivariate logistic regression models. Results:The incidence of low birth weight was 10.6%. Multivariate logistic regression showed that pre-eclampsia (RR 3.9; 95% CI 3.6-4.2), eclampsia (RR 5.4; 95% CI 4.1-6.9), chronic hypertension (RR 2.8; 95% CI 2.1-3.8), maternal anaemia (RR 1.7; 95% CI 1.4-2.2), HIV status (RR 0.8; 95% CI 0.7-0.8), smoking during pregnancy (RR 1.9; 95% CI 1.0-3.5), caesarean section delivery (RR 1.4; 95% CI 1.3-1.5), placental abruption (RR 3.7; 95% CI 1.3-4.7), placenta previa (RR 6.6; 95% CI 4.8-9.3), PROM (RR 2.5; 95% CI 1.9-3.3), maternal underweight (RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.2-1.6), and obesity (RR 1.2; 95% CI 1.1-1.4) and female gender of baby were associated with delivery of low birth weight infants. On the other hand, LBW infants had increased risk of neonatal jaundice (RR 2.7; 95% CI 1.2-6.1), being delivered preterm (RR 2.0; 95% CI 1.8-2.3), Apgar score (<7) at fifth minute (RR 5.5; 95% CI 4.5-6.6) and early neonatal death (RR 3.5; 95% CI 2.6-4.6). Conclusions:Low birth weight is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Early identification of risk factors for low birth weight through prenatal surveillance of high risk pregnant women may help to prevent these adverse perinatal outcomes.

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 3 July 2015

Received in revised form 6 October 2015

Accepted 15 October 2015

Available online 1 January 2016

Keywords:

Low birth weight

Risk factors

Adverse perinatal outcome

Registry

Tanzania

E-mail :jmmahande@gmail.com Foundation project:This study was supported by Norwegian Council for Higher education program and Development Research (NUFU) (grant No. R01-KCMC0043005).

1. Introduction

Low birth weight (LBW) is defined as birth weight of a live born infant of less than 2 500 g regardless of gestational age[1]. There is a strong relationship between preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction and low birth weight[2]. Low birth weight is a public health problem in developing countries especially in sub Saharan Africa. It is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes such as perinatal asphyxia, prematurity, hypothermia, necrotizing enterocolitis, respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal jaundice, anemia, low Apgar score at 1st and 5th minutes and perinatal mortality[2- 4]. Infants who are born with low birth weight experiences long term life consequences such as coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, neurological sequeland recurrence of low birth weight in subsequent siblings[3, 5, 6].

Globally, the prevalence of low birth weight ranges from 3% to 15%[1]. However, the lowest prevalence of low birth weight of 3%)has been reported in China[1]. Recent estimates show that the prevalence of low birth weight in sub-Sahara Africa is 12%[1]. The Tanzania demographic health survey reported prevalence of LBW of 16%[7].

Several factors have been associated with LBW including poor maternal nutrition before and during pregnancy, maternal diseases such as maternal anemia, chronic hypertension, renal diseases and heart diseases, alcohol, smoking, drug use during pregnancy, parity, low maternal education, maternal occupation, short stature, extreme maternal age, induced labor or elective caesarean section, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse[1-3, 8-13].

Some interventions such as provision of pre-conceptual counseling and health services such as family planning services also have shown significant improvement in maternal health hence reduces prevalence of low birth weight[1].

Despite the fact that LBW has been reported to account for perinatal morbidity and mortality, there are few studies in Tanzania which have assessed on the risk factors for low birth weight and associated perinatal morbidity and mortality. These studies have also reported some contradicting findings and used cross sectional data which makes it impossible to estimate incidence of LBW and accurate ascertainment of associations between various risk factors and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with LBW. The incidence and perinatal outcomes among LBW infants have not yet been extensively explored in Tanzania. Reduction in incidence of low birth weight may lead to improvement in child survival[14]. The aim of this study was to determine incidence and risk factors for low birth weight, and associated perinatal morbidity and mortality in northern Tanzania which will in turn help to design appropriate interventions to prevent adverse perinatal outcomes associated with LBW, and help to accelerate efforts towards the achievement of Millenium Development Goal 4.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and setting

A retrospective study was designed using Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) medical birth registry data for women who delivered singleton infants for the period from 2000 to 2013 at the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. KCMC is a referral and teaching hospital. It is located in Kilimanjaro region in Northern Tanzania. It serves a population over 11 million people from the nearby communities within the region and from the nearby regions. It has an average delivery rate of 4 000 births per year.

2.2. Study population

All women who delivered singleton infants at KCMC from 2000 through 2013 who had complete birth records were eligible for this study. Women with multiple gestations, stillbirths and deliveries with birth defects were excluded. Multiple gestations and those with birth defects were excluded because they have a higher risk rate of low birth weight which could lead to overestimation of studied adverse pregnancy outcomes. The final sample comprised of 37 799 singleton births.

2.3. Study variables

Main outcome measures were low birth weight, early neonatal death and morbidity (jaundice, preterm birth, Apgar score and neonatal infection). Low birth weight was defined as birth weight of less than 2 500 g. We included only infants born at 28 weeks of gestation. The independent variables included; maternal demographic characteristics, maternal weight during pregnancy, maternal diseases (e.g. chronic hypertension and diabetes mellitus, maternal anemia, preeclampsia and eclampsia), maternal risk behaviors (e.g. smoking and drinking alcohol during pregnancy).

2.4. Data source

This study utilized medical birth registry data from KCMC. The medical birth registry of KCMC was established in the year 1999 as a collaborative project between medical birth registry of Norway through University of Bergen in Norway and KCMC via Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College. It has been in operation since 2000 recording all births at KCMC in a computerized database. Information recorded in the birth registry has been described in detail elsewhere[15]. In summary, information collected includes maternal and paternal sociodemographic characteristics, maternal health before pregnancy, during pregnancy, after delivery and child status.

2.5. Data collection

A trained midwife nurses conducts interviews on daily basis using a standardized questionnaire for all women who deliver at the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology within 24 hours ofdelivery or as soon as mothers have recovered in case of complicated deliveries. In addition, information of neonates who are admitted at neonatal care unit is also recorded in neonatal registry form. Data from medical records is also extracted from the patient’s file. Verbal consents are sought from each individual mother prior the interview.

2.6. Ethical clearance

The ethical approval was obtained from the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical College University (KCMU-Co) research ethics committee prior to commencement of the study. Permission to use medical birth registry data was obtained from the KCMC hospital and medical birth registry administration. Confidentiality of information was adhered by the use of maternal unique identification number.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 16.0, (SPSS Inc. Chicago, III). Descriptive statistics were summarized using proportions, frequency, mean, and standard deviation (for normal distribution data). Student t test was used to compare means between groups for continuous variables. We used chi-square test (χ2) to establish the relationship between various risk factors and LBW. The relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for factors associated with LBW and adverse perinatal outcomes was estimated using multivariate logistic regression model while controlling for the potential confounding. A P value of less than 0.05 (two sided) was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the study participants

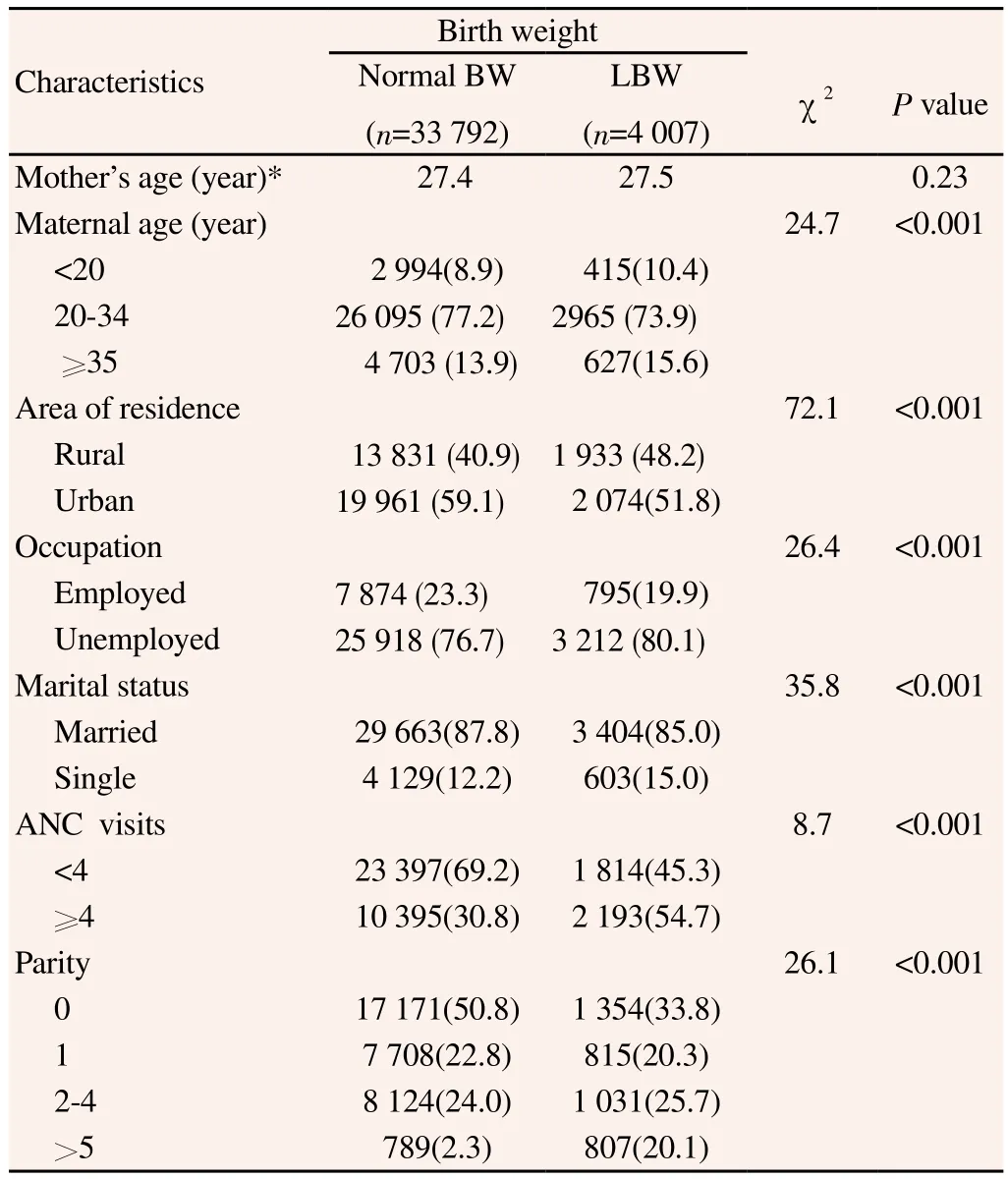

The sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. A total of 37 799 singleton births were analyzed. Of these, 4007 had low birth weight (LBW) this constitutes to an incidence of 10.6%. There was no difference in mean age between women with normal birth weight and those with low birth weight infants (27.4±6.0 years vs 27.5±6.3 years). Women residing in rural area had higher rate of low birth weight as compared to those who were residing in the urban area [12.3% ((1 933/1 5764) vs. 9.5% (2 075/21 794), respectively; P<0.001]. Mothers with low birth weight infants were more likely to be single as compared to those who had normal birth weight (14.7% vs. 11.5%, respectively; P<0.001). In addition, mothers with low birth weight were more likely to have 4 visits as compared to mothers with normal birth weight infants (17.3% vs. 7.2%, P<0.001) respectively, and were also more likely to have higher parity as compared to women in the comparison group.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the study participants.

3.2. Factors associated with low birth weight

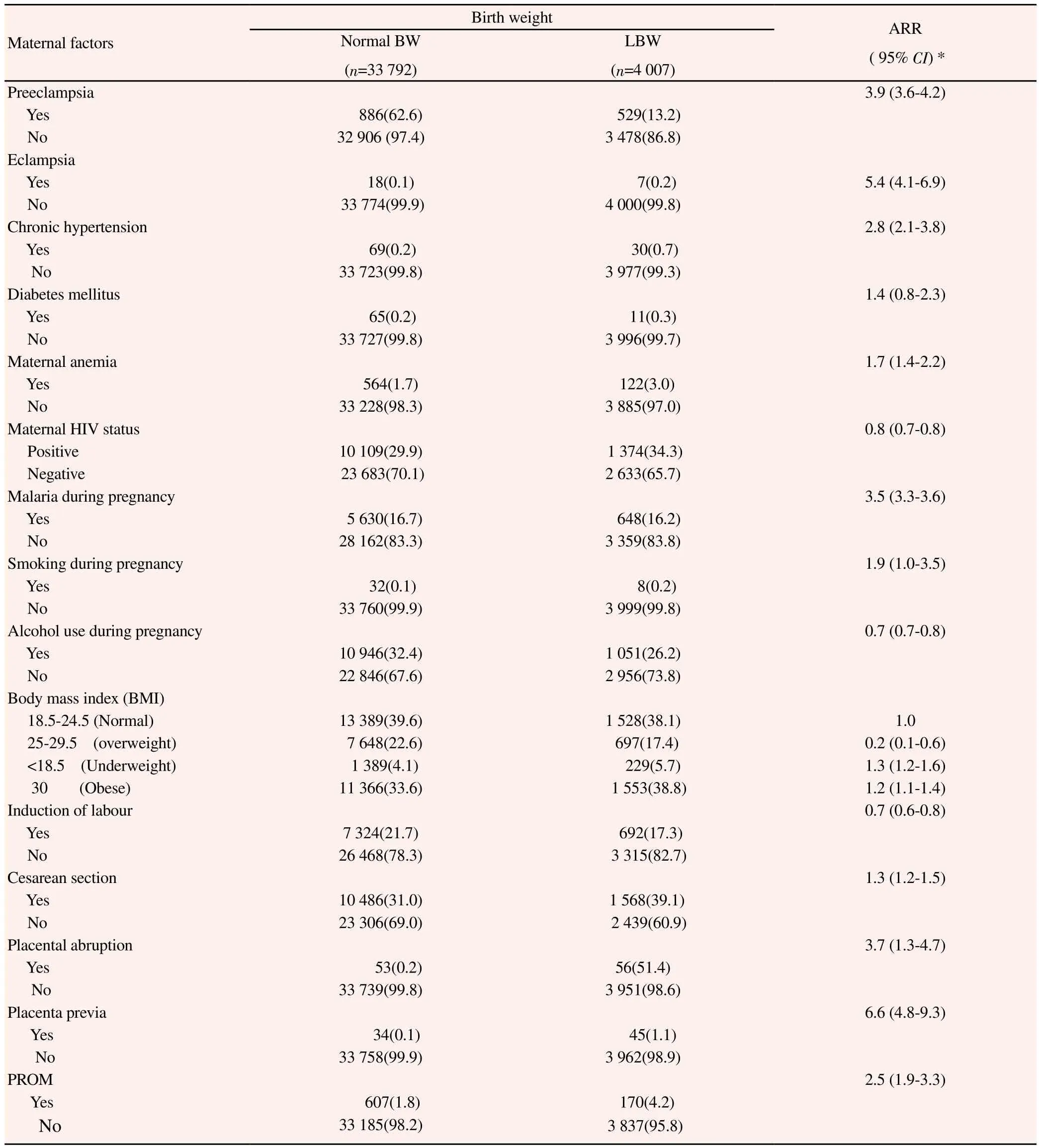

Results from multivariate analysis have been displayed in Table 2. The common risk factors for delivering LBW infants were preeclampsia (RR 3.9, 95% CI 3.6-4.2), eclampsia (RR 5.4; 95% CI 4.1-6.9), chronic hypertension (RR 2.8; 95% CI 2.1-3.8), maternal anemia (RR 1.7; 95% CI 1.4-2.2), malaria during pregnancy (RR 3.5; 95% CI 3.3-3.6), smoking during the current pregnancy (RR 1.9; 95% CI 1.0-3.5), delivery by cesarean section (RR 1.4; 95% CI 1.3-1.5), placental abruption (RR 3.7; 95% CI 1.3-4.7), premature rupture of membrane (RR 2.5; 95% CI 1.9-3.3), placenta previa (RR 6.6; 95% CI 4.8-9.3), maternal underweight (RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.2-1.6), and obesity(RR 1.2; 95% CI 1.1-1.4). Diabetes mellitus was associated with low birth weight but this association did not reach statistical significance. Other known risk factors for LBW such asalcohol drinking and induced labour and maternal HIV were not significantly associated with LBW in this population after.

Table 2 Results of multiple logistic regression model for risk factors of low birth weight.

3.3. Perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with Low birth weight

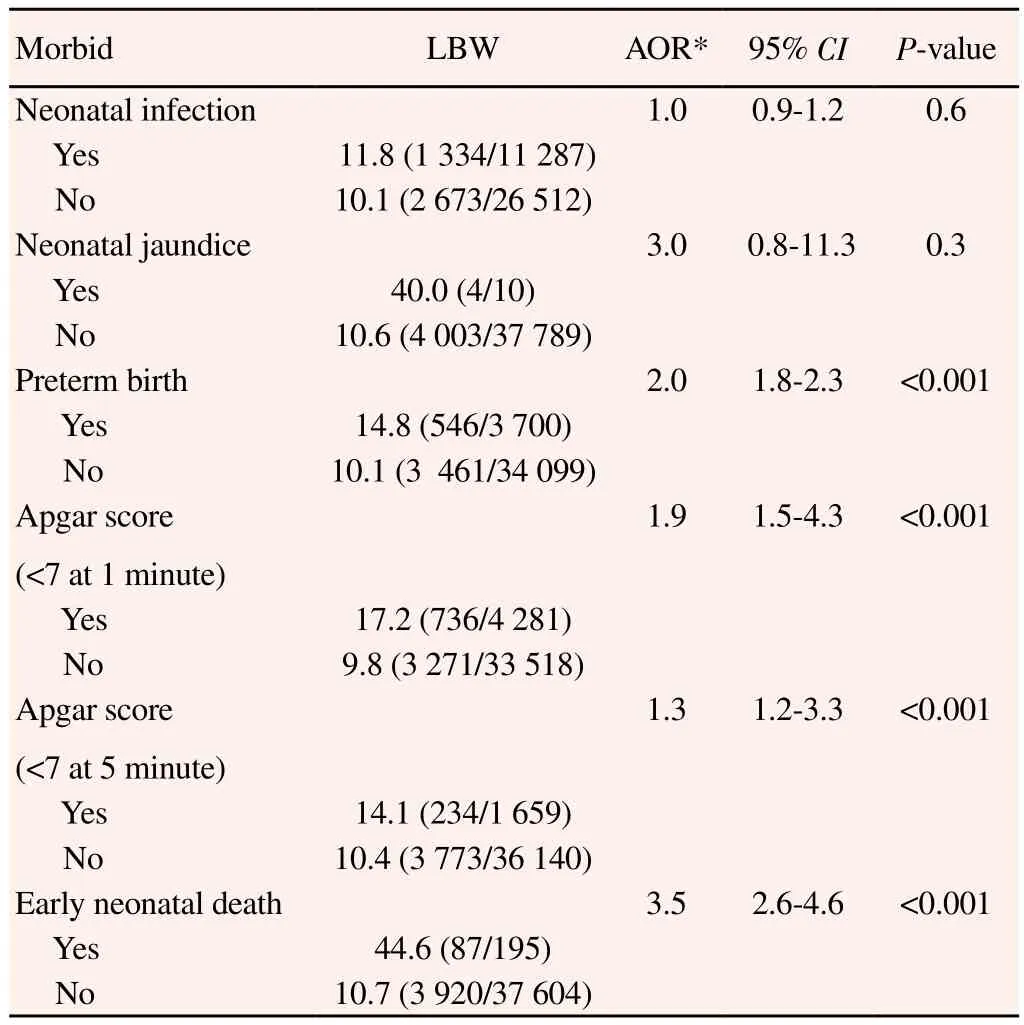

Table 3 summarizes results from multivariate logistic analysis for adverse perinatal outcomes associated with LBW. We found that LBW infants had increased risks of Low Apgar score (<7 at 1 min) (OR 4.9; 95% CI 4.5-5.3 and OR 6.6; 95% CI 6.0-7.3) respectively, premature birth (OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.8-2.3), early neonatal death (OR 3.5; 95% CI 2.6-4.6). Neonatal jaundice was associated with low birth weight but this association did not reach statistical significance (OR 3.0; 95% CI 0.8-11.3). Other known perinatal morbidity associated with LBW such as neonatal infection, were not associatedwith low birth weight after controlling for potential confounding factors.

Table 3 Perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with low birth weight (%).

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated incidence of low birth, risk factors, and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with low birth weight using medical birth registry data from KCMC. We found that the incidence of LBW was 10.6%. Preeclampsia, eclampsia, chronic hypertension, maternal anemia, and delivery by cesarean section were important risk factors for low birth weight. In addition, infants born with low birth weight had greater risk being born preterm, early neonatal death having a low Apgar score at first and fifth minutes as compared with infants who were born with normal weight.

The incidence of low birth weight in our study corresponds with previous study[12], it also falls within the estimate of 3%-15%, reported by World Health Organization[1]. It is however lower than the 14.6% reported by Coutinho[4]. The difference in incidence could be explained by size of study population, diagnostic criteria, nature of population and difference in prevalence of risk factors for low birth weight.

A previous study has reported an association between preeclampsia/eclampsia with low birth weight[16]. Similar to our study women with preeclampsia and eclampsia had increased risk to deliver low birth weight infants (5.8 and 8.4 folds respectively) compared to women without preeclampsia and eclampsia. Abnormal implanted placenta which predisposes a woman to preeclampsia is thought to result in poor uterine and placental perfusion yielding a state of hypoxia which affects growth of an infant which leads to low birth weight. Maternal hypertension has been reported to be associated with LBW in previous studies[3, 12, 17, 18]. Similar to our study, women with chronic hypertension had more than threefold increase in delivering LBW infants compared to non-chronic hypertensive women. The high risk of low birth weight among women with chronic hypertension could be explained by the effect of preeclampsia in this group which necessitates early termination of pregnancy to prevent futurematernal and fetal complications. Hence this may lead to delivery of premature low birthweight infants.

A previous study done in India demonstrated the association between maternal diabetes with increased newborn weight[19]. Consistent to our study, mothers with diabetes mellitus were three times more likely to deliver LBW infants as compared to nondiabetic mellitus mothers. However, this association did not rich statistically significant which could be due to small number of mothers with diabetes. Our data also showed that delivery by cesarean section was significantly associated with increased risk of LBW. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere[3]. The increased risk of delivering infants among women who underwent caesarean section could explianed by other co-morbidities which necessitated the option of cesarean section delivery to save the mother or fetus, such as hypertension, bleeding and diabetes mellitus.

Smoking during pregnancy has been associated with delivery of low birth weight infant in previous study[18]. This was in agreement with our study; however the association in the present study was not strong compared with that was reported by the previous investigators. This could be explained by low frequency of smoking among women in the studied population. It is also important to note that smoking is uncommon practice among women in Tanzania.

Previous studies have shown that some sociodemographic factors such as marital status (being single), occupation and residing in rural area are associated with increased risk of delivering an infant with LBW [12, 13, 20]. Similar observations were revealed by our study. Occupation particularly unemployed women are prone to poor nutrition due to lack of financial support. Residence, particularly rural, is a risk to LBW due to insufficient health services and education on maternal issues.

Other studies have shown there is association between neonatal infection and LBW [9, 17] in contrast to our study. This could be due to poor recording of specific incidents of infection in our neonates. In the present study neonatal jaundice was a significant perinatal morbidity associated with LBW. This is consistentwith previous investigators [21]. In our study LBW infant were 3-fold more likely to develop jaundiced as compared to infant who were born with normal weight.

Countinho and colleagues found an association between low birth weight and a low Apgar score in the first and fifth minutes (4). Similar to our study, infants born with low birth weight had nearly 2-fold increased risk of Apgar score in the first and fifth minutes respectively. Low birth weight has been associated with increased risk of early neonatal death in several studies (5, 17, 18, 21). Our study support the previous investigators; we found that LBW infants had 4-fold increased risk to early neonatal death as compared to normal weight infants.

The use of maternally linked data has several advantages. First, the data contained maternal demographic and infant medical informationwhich enabled us to assess association of maternal characteristics and fetal outcome. Secondly, our link data gave us large sample size which helps to increase accuracy of data presentation. Third, we used data which were collected using standardized questionnaire which enabled us to obtain data that is complete and accurate.

Despite the strengths of our study, the following limitations should be taken into account while interpreting our results. First, selection bias; since this was the hospital based study; there is a possibility that women who delivered in our setting might be a high risk group because most women with complicated pregnancy tends to be referred to a tertiary health facility for delivery, so if this happened in our case it may lead to overestimation of the reported results. Secondly, the possibility of underreporting of early neonatal death and other co-morbidity due to limited follow up of mothers with their infants for women who are discharged earlier. The registry data record only mothers who stayed in hospital within one week after delivery. The underreporting also could be attributed to high rate of home delivery in Tanzania, but this may not be the case in the studied population where health facility delivary rate is more than 90%. Third, the failure to take into account factors which are not recorded in birth registry example neurological development which is important outcome of low birth weight.

The incidence and risk factors of LBW in our study corresponds to other studies in region and population based studies in high income countries. Preeclampsia, eclampsia, chronic hypertension, maternal anemia and delivery by cesarean section were the significant risk factors for LBW. Low birth weight is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Our results provide clinicians and mothers with important information which will be considered during caring and counseling pregnant women with risk factors for LBW, also mothers with LBW infants to prevent adverse perinatal morbidity and mortality. We recommend more research to be done on causes and prevention of risk factors associated with LBW.

Declare of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank all doctors and nurses at KCMC who participated in data collection. We also extend of appreciation to all women who volunteer to provide their information making this study possible to be conducted. We thank for the Norwegian Council for Higher education program and Development Research (NUFU) for funding the KCMC Medical birth registry (R01-KCMC0043005). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

[1] World Health Organization and UNICEF. Low birth weight:country, regional and global estimates. New York. Geneva:WHO; 2013.

[2] Dutta DC. A text book of obstetrics. 7th ed. London:Chintamoni Das Lane; 2011.

[3] Coutinho PR, Cecatti JG, Surita FG. Perinatal outcomes associated with low birth weight in a historical cohort. Reprod Health 2011;8:18.

[4] Wariki WM, Mori R, Boo NY, Cheah IG, Fujimura M, Lee J, et al. Risk factors associated with outcomes of very low birth weight infants in four Asian countries. J Paediatr Child Health 2013; 49(1):E23-E27.

[5] Lim WY, Lee YS, Tan CS, Kwek K, Chong YS, Gluckman PD, et al. The association between maternal blood pressures and offspring size at birth in Southeast Asian women. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth 2014; 14:403.

[6] Mahande MJ, Daltveit AK, Obure J, Mmbaga BT, Masenga G, Manongi R, et al. Recurrence of preterm birth and perinatal mortality:A registry based study. Trop Med Int Health 2013; 18 (8):962-967.

[7] National Bureau of Statistics (Tanzania), & ICF Macro. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Dar es salaam/Calverton:NBS, ICF Macro; 2010.

[8] Demelash H, Motbainor A, Nigatu D, Gashaw K, Melese A. Risk factors for low birth weight in Bale zone hospitals, South-East Ethiopia :a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2015; 15:264.

[9] Kayode GA, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Agyepong IA, Ansah E, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Contextual risk factors for low birth weight:A multilevel analysis. PLoS One 2014;9(10)::e109333. DOI:10.1371/ journal.pone.0109333.

[10] Mmbaga BT, Lie RT, Olomi R. Cause-specific neonatal mortality in a neonatal care unit in Northern Tanzania a registry based cohort study. BMC Pediatrics 2012; 12:116.

[11] Feresu SA, Harlow SD, Woelk GB. Risk factors for low birthweight in Zimbabwean women:A secondary data analysis. PLoS One 2015;10(6) e0129705. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129705. eCollection 2015.

[12] Jammeh Abdou, Johanne Sundby SV. Maternal and obstetric risk factors for low birth weight and preterm birth in rural Gambia:a hospital-based study of 1579 deliveries. Open J Obstet & Gynecol 2011; 1:94-103.

[13] Choudhary AK, Choudhary A, Tiwari SC, Dwivedi R. Factors associated with low birth weight among newborns in an urban slum community in Bhopal. Indian J Public Health. 2013; 57(1):20-23.

[14] United Nations Chidren Fund. Improving child nutrition:the achievable imperative for global progress. New York:UNICEF;2013.

[15] Mmbaga BT, Lie RT, Kibiki GS. Transfer of newborns to neonatal care unit:a registry based study in Northern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy and Child birth 2011; 11:68.

[16] Mahande MJ, Daltveit AK, Mmbaga BT, Masenga G, Obure J, Manongi R, et al. Recurrence of preeclampsia in northern Tanzania:A registrybased cohort study. Plos One 2013; 8(11)e79116. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0079116.

[17] Kintiraki E, Papakatsika S, Kotronis G, Goulis DG, Kotsis V. Pregnancy induced hypertension. Hormones 2015;14(2):211-223.

[18] Juárez SP, Merlo J. Revisiting the effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring birth weight:a quasi-experimental sibling analysis in Sweden. PLoS ONE 2013; 8(4):e61734.

[19] Ellerbe CN, Gebregziabher M, Korte JE, Mauldin J, Hunt KJ. Quantifying the impact of gestational diabetes mellitus, maternal weight and race on birth weight via quantile regression. PLoS One 2013; 8(6):DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0065017.

[20] Patel PB, Bavarva NR, Patel MJ, Rana JJ, Mehta SR, Bansal RK. Sociodemographic and obstetrical factors associated with low birth weight:community based retrospective study in an urban slum of western India. Appl Med Res 2015; 1(3):94-98.

[21] Mahande MJ, Daltveit AK, Mmbaga BT, Obure Joseph, Masenga G, Manongi R, et al. Recurrence of perinatal death in Northern Tanzania:a registry based cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2013, 13:166.

doi:Document heading 10.1016/j.apjr.2015.12.014

*Corresponding author:Michael J Mahande, Institute of Public Health Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania.

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2016年1期

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2016年1期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction的其它文章

- Diagnostic and decision-making difficulties:Placenta accreta at nine weeks’gestation

- Male masturbation device for the treatment of premature ejaculation

- Analysis of the androgen receptor CAG repeats length in Iranian patients with idiopathic non-obstructive azoospermia

- Returning of cyclicity in infertile Corriedale Sheep with natural progesterone and GnRH based strategies

- Effect of cooling to different sub-zero temperatures on boar sperm cryosurvival

- Milk supplements in a glycerol free trehalose freezing extender enhanced cryosurvival of boar spermatozoa