Environmental enrichment combined with fasudiltreatment inhibits neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 region and ameliorates memory deficits

Gao-Jing Xu, Qun Zhang, Si-Yue Li Yi-Tong Zhu Ke-Wei Yu Chuan-Jie Wang,Hong-Yu Xie , Yi Wu

Abstract Currently, no specific treatment exists to promote recovery from cognitive impairment after a stroke. Dysfunction of the actin cytoskeleton correlates well with poststroke cognitive declines, and its reorganization requires proper regulation of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) proteins.Fasudil downregulates ROCK activation and protects neurons against cytoskeleton collapse in the acute phase after stroke. An enriched environment can reduce poststroke cognitive impairment. However, the efficacy of environmental enrichment combined with fasudil treatment remains poorly understood. A photothrombotic stroke model was established in 6-week-old male C57BL/6 mice. Twenty-four hours after modeling, these animals were intraperitoneally administered fasudil (10 mg/kg) once daily for 14 successive days and/or provided with environmental enrichment for 21 successive days. After exposure to environmental enrichment combined with fasudil treatment, the number of neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region increased significantly, the expression and proportion of p-cofilin in the hippocampus decreased,and the distribution of F-actin in the hippocampal CA1 region increased significantly. Furthermore, the performance of mouse stroke models in the tail suspension test and step-through passive avoidance test improved significantly. These findings suggest that environmental enrichment combined with fasudil treatment can ameliorate memory dysfunction through inhibition of the hippocampal ROCK/cofilin pathway, alteration of the dynamic distribution of F-actin, and inhibition of neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 region. The efficacy of environmental enrichment combined with fasudil treatment was superior to that of fasudil treatment alone. This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Fudan University of China (approval No. 2019-Huashan Hospital JS-139) on February 20, 2019.

Key Words: cognitive; environment; hippocampus; injury; neuroprotection; pathway; repair; stroke

Introduction

Poststroke cognitive impairment is a common complication in ischemic stroke patients, and its prevalence ranges from 25% to 30% (Kalaria et al., 2016). The occurrence of cognitive impairment can even reach 71% in survivors with good clinical recovery at 3 months after stroke (Jokinen et al.,2015). Although pharmacological interventions and physical training are two promising approaches to promote functional recovery and anatomical reorganization, no specific treatment currently exists to improve cognitive recovery after a stroke(Mijajlovi? et al., 2017). The hippocampal lesion accounts for poststroke cognitive impairment (Sun et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2020). Studies have revealed that dysfunction of actin cytoskeleton regulation correlates well with cognitive declines after stroke (Mack et al., 2016; Hoffmann et al., 2019). Thus,reorganization of the hippocampal actin cytoskeleton may be an appropriate option to promote poststroke cognition.However, studies on approaches to promote hippocampal actin cytoskeleton reorganization are lacking.

Actin cytoskeleton reorganization requires proper regulation of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) proteins, which are ubiquitously present in all tissues (Amin et al., 2019). The appropriate balance of cofilin phosphorylation, the downstream effector of LIM-kinase 1 and LIM-kinase 2 in the ROCK family, is necessary for actin cytoskeleton reorganization (Hashimoto et al., 1999; Sumi et al., 2001). Furthermore, ROCK pathway activation has been observed after ischemic brain injury(Nunes et al., 2010). Fasudil (also known as HA-1077), a widely used ROCK inhibitor, has shown clinical effectiveness in acute ischemic stroke patients (Shibuya et al., 2005). In addition to its neuroprotective potential via suppressing the inflammatory response (Ding et al., 2010), promoting angiogenesis (Zhai and Feng, 2019), reducing cerebral infarct size, and rescuing the spine and synaptic properties (Li et al., 2009), fasudil has been shown to downregulate ROCK activation and promote cognitive recovery through an anti-apoptotic mechanism in a chronic ischemic model (Yan et al., 2015). Moreover,fasudil can protect neurons against cytoskeleton collapse via cytoskeleton reorganization in the peri-infarct area (Wei et al., 2014). Recently, some drug combination strategies have shown synergistic effects after stroke. For example, coadministration of fasudil and tissue plasminogen activator showed promising effects on attenuating stroke-induced neurological deficits and expanding the time window for ischemic stroke therapy (Fukuta et al., 2018; Knecht et al.,2018); fasudil combined with ozagrel, a thromboxane A(2)synthase inhibitor, showed a greater neuroprotective effect on reducing cerebral infarction than either drug administered alone (Koumura et al., 2011). A previous study demonstrated that early constraint-induced movement therapy combined with fasudil treatment can promote motor performance in rats with acute ischemia (Liu et al., 2016). However, studies on combination therapy including fasudil and nonpharmacological recovery interventions in the chronic stage are limited.

Previous studies demonstrated that environmental enrichment(EE), a rearing condition including various toys to provide increased physical, cognitive, and social interactions compared with standard conditions (van Praag et al., 2000; Huang et al.,2016), exhibited neuroprotective effects through different mechanisms, including inflammatory cytokine reduction(Gon?alves et al., 2018), neurogenesis (Matsumori et al.,2006), and cell proliferation (Klein et al., 2017). Moreover,because it decreased neuronal death in the hippocampus, EE was effective in reducing cognitive impairment after cerebral ischemia (Kato et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2017). A previous study showed that EE combined with 17beta-estradiol accelerated cognitive recovery after focal brain ischemia (S?derstr?m et al., 2009). Considering that both EE and fasudil lead to substantial cognitive recovery and anatomical reorganization in the hippocampus after stroke, it is hypothesized in this study that fasudil combined with EE provides greater benefit than either EE or fasudil treatment alone. Therefore, this study aimed to further explain the involvement of ROCK2/cofilin signaling in poststroke hippocampal actin cytoskeleton reorganization and analyze the potential neuroprotective effect of EE combined with fasudil treatment in poststroke cognitive recovery compared with either EE or fasudil treatment alone.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All procedures described in this study were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Fudan University (approval No. 2019-Huashan Hospital JS-139) on February 20, 2019. A total of 60 male C57BL/6 mice (specific pathogen free level,purchased from JSJ Company, Shanghai, China, license No.SCXK(Hu)2013-0006), aged 6 weeks and weighing 20–22 g, were housed under a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle at 23 ± 2°C, withad libitumaccess to water and food. All experiments were designed and reported according to the Animal Research: Reporting ofIn VivoExperiments (ARRIVE)guidelines. All sample sizes for the assessment parameters were calculated based on previous studies using a sample size calculator.

Experimental design

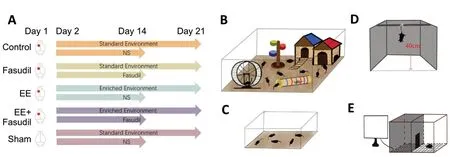

After 1 week of habituation to the new environment, the animals were prepared for photothrombotic stroke induction.The mice were randomly divided into five groups (n= 12 each;Figure 1A): (I) sham group: received a sham surgery,were injected with normal saline for 14 days starting from 24 hours after surgery, and were kept in a standard environment for 21 days. The other four groups were subjected to photothrombotic ischemia in the sensorimotor area and subsequently treated for 21 days as follows: (II) control group:injected with normal saline for 14 days starting from 24 hours after stroke and kept in the standard environment until the end of the experiment; (III) fasudil group: intraperitoneally administered 10 mg/kg fasudil (1 mg/mL in saline; Adamas,Shanghai, China, once a day) for 14 days starting from 24 hours after stroke (Huang et al., 2018) and kept in the standard environment; (IV) EE group: exposed to EE starting at 24 hours poststroke and maintained for 21 days; and (V) EE+ fasudil group: given the same dose of fasudil as the fasudil group and exposed to EE for 21 days.

Photothrombotic stroke model establishment

After being anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis,MO, USA), the mice were placed in a stereotactic device(RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China) with the skull exposed.The whole skull was covered with an opaque template that exposed a circular region of the left sensorimotor cortex(Bix et al., 2013; Clarkson et al., 2013; Harrison et al., 2013)(coordinates: rostral to caudal, 2.5–1.5 mm; medial to lateral,0–4 mm; relative to bregma). As soon as the mice were given 1% Rose Bengal (0.01 mL/g of body weight, dissolved in 0.9%NaCl; Sigma-Aldrich) by intravenous injection, the targeted sensorimotor cortex was illuminated with a 532-nm green laser beam (50 mW) for 10 minutes at maximum output.During the whole procedure, the body temperature was monitored and maintained with a heating lamp.

Housing conditions

The animals were kept in two housing conditions: a standard environment or an EE condition. In the EE condition, the animals were maintained in 545 mm × 395 mm × 200 mm cages (with up to 10 animals per cage) containing various toys,such as chains, runners, ladders, and pipelines (Figure 1B).For the standard environment, the animals were maintained in 294 mm × 190 mm × 130 mm cages (with up to five animals per cage;Figure 1C). These objects were changed every day as described in a previous study (Zhang et al., 2019).

Behavioral tests

All behavioral tests were conducted after the 21-day intervention and in the light phase of the diurnal cycle,between 13:00 and 17:00. The animals were subjected to the tail suspension test, and after one day of rest, they underwent the step-through passive avoidance test.

Tail suspension test

After 1 hour of habituation in the experimental environment,each mouse was suspended 40 cm above the floor with an adhesive tape placed approximately 1 cm from the tip of the tail (Figure 1D). At the beginning of the test, the animals exhibited escape behaviors, which after a period of struggle, became more subtle. These subtle movements were considered as the immobility time. The activities of the mice were recorded by a camera, and the immobility time during the last 4 minutes of a 6-minute testing period was calculated.During the test, the mice were recorded separately to prevent animals from observing or interacting with each other. After each animal completed the test, the suspension box was thoroughly cleaned to eliminate olfactory effects (Can et al.,2012).

Step-through passive avoidance test

The step-through passive avoidance test was performed to evaluate the animals’ short-term memory. A chamber(130 mm × 210 mm × 300 mm) was evenly divided into two compartments by a sliding door (Figure 1E). In the acquisition trial, each mouse was first placed in the light compartment and allowed to explore for 10 seconds. Then, the sliding door was opened, allowing the mouse to move to the dark side. Upon entering the dark compartment completely, the mouse was immediately given a 0.5-mA electric shock for 1 second through the steel floor grid. Then, the mouse was returned to its home cage. After 24 hours, for the retention trial, each mouse was placed in the light compartment again,and the latency to enter the dark compartment was recorded.If the latency exceeded 300 seconds, it was recorded as 300 seconds. The number of times that the mouse traveled through the sliding door was also recorded (Kameyama et al.,1986; Zhou et al., 2019). Meanwhile, the footprints of the animal were recorded during the retention trial to determine the travel pattern (Figure 1E).

Sample preparation

The mice were sacrificed after the behavioral tests. After being deeply anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich), the mice were transcardially perfused with normal saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). The entire brain was removed and immersed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer(pH 7.2) and then placed in 10% and 20% sucrose for 6 hours sequentially at 4°C until it sank in 30% sucrose. Subsequently,the samples were embedded in optical coherence tomography compound (Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek, Japan) and cut into 20-μm-thick sagittal sections.

Western blot analysis

The hippocampus was isolated and lysed in radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai,China) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Melone Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.,Dalian, China). An aliquot of 40 μg of total protein was separated by size via 10% sodium salt-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk (Beyotime) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (Beyotime) for 1 hour,the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti-cofilin antibody (1:1000;rabbit; ab42824, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-cofilin(phospho S3) antibody (1:1000; rabbit, ab12866, Abcam), and anti-beta-actin antibody (1:1000; rabbit; ab8227, Abcam).The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies (1:3000; goat antirabbit; A16104SAMPLE, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. The blots were visualized using the Chemistar High-sig enhanced chemiluminescence Western Blotting Substrate (Tanon, Shanghai, China). All protein bands were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (Kim et al., 2014).

Nissl staining

The experiment was performed in accordance with the Nissl staining kit instructions (Solarbio, Beijing, China). After blotting with a cresyl violet staining solution (Solarbio) for 45 minutes at room temperature, the sections were washed and differentiated with a Nissl differentiation solution (Solarbio).Then, the sections were immersed in distilled water to stop the reaction. Subsequently, the change in cell morphology in the hippocampal CA1 region was photographed under a microscope using 10× and 20× magnifications. Three discontinuous slides were chosen for quantitative analysis for each animal. The number of surviving pyramidal neurons in a region of interest (200 μm × 100 μm) in the hippocampal CA1 region was recorded using the plugin “Cell counter” for ImageJ software (Plata et al., 2018).

F-actin distribution assay

Phalloidin specifically binds to F-actin, and because of its low molecular weight, it can penetrate the cell membrane without pretreatment; thus, secondary antibodies are not necessary for further analysis (Katanaev and Wymann, 1998). Brain sections were cut through the hippocampus with a cryostat(20 μm, coronal), incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanatelabeled phalloidin (1:500; peptide from Amanita phalloides,MFCD00147902, Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 minutes at room temperature, and observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope with a 60× oil lens (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar,Germany). XY scanning was used to capture the horizontal plane as described previously (Li et al., 2007). Single-plane images of the hippocampal CA1 region (50 μm × 50 μm)were collected and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software(v.6.0, Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA) as described in a previous study (Zhang et al., 2014). The threshold function of Image-Pro Plus was used to set the threshold intensity and automatically score the puncta of the CA1 field based on the fluorescence intensity (Xiong et al., 2015). The immunopositivity was obtained from three fields per slide;three slides from each animal were chosen for analysis, and the group means were calculated.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean (SD) across the groups and were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Company, San Diego, CA, USA). Significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test among experimental groups. APvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

EE combined with fasudil improves the morphological changes in the hippocampal CA1 region of stroke mice

Nissl staining was conducted to show morphological changes in the hippocampal CA1 region. The results revealed that photothrombotic stroke induced greater neuronal loss in the hippocampal CA1 region than in the sham group on day 21 (P< 0.05), as shown by diamond- and triangle-shaped neurons(Figure 2A1andA2). The neuron densities of the EE, fasudil,and EE + fasudil groups were significantly higher than that of the control group (P< 0.05;Figure 2B1–E1andB2–E2). A higher neuron density was observed in the EE + fasudil group than in the EE and fasudil groups (P< 0.05;Figure 2).

EE combined with fasudil inhibits phosphorylation of cofilin in the hippocampus of stroke mice

Phosphorylated cofilin (p-cofilin, inactive form) in the hippocampus was chosen as a core indicator to evaluate whether EE and fasudil altered the ROCK activity (Xue et al.,2019). An increase in p-cofilin expression was observed in the control group after photothrombotic stroke compared with the sham group (Figure 3A), in addition to an increase in phosphorylation of cofilin (P< 0.05;Figure 3B). After administering fasudil, both the expression and proportion of p-cofilin were decreased significantly compared with the control group (P< 0.05;Figure 3BandC). The EE housing condition suppressed the phosphorylation of cofilin compared with the control group (P< 0.05;Figure 3C). The combination of EE and fasudil suppressed p-cofilin expression and phosphorylation of cofilin compared with the control group (P< 0.05), and it also decreased the expression and proportion of p-cofilin compared with the EE group (P< 0.05;Figure 3BandC). The difference in cofilin expression among the five groups was not significant (P> 0.05;Figure 3D).

Figure 1|Schematic diagram of the experiment design.

Figure 2|Effect of EE combined with fasudil treatment in the hippocampus of mice at 21 days after stroke.

Figure 3|Effect of EE combined with fasudil treatment on the protein expression and phosphorylation of cofilin in the hippocampus of stroke mice.

EE combined with fasudil treatment alters the F-actindistribution in the hippocampal CA1 region of stroke mice

Phalloidin can bind to F-actin and reveal its distribution;therefore, phalloidin staining was performed. Under normal conditions, F-actin appears as tiny puncta in the CA1 region,and the intensity of the fluorescence signal may be weakened in degenerated neurons (Zhang et al., 2014; Xiong et al.,2015). In the control group, the F-actin immunopositivity in the hippocampal CA1 region was lower than that in the sham group on day 21 post stroke (Figure 4A1,A2,E1andE2). The F-actin distribution in the hippocampal CA1 region was significantly increased in the EE, fasudil, and EE + fasudil groups compared with that in the control group (P< 0.05;Figure 4B1–D1andB2–D2). Quantitative analysis showed that the combination of EE + fasudil treatment resulted in high immunopositivity of F-actin compared with the EE and fasudil groups (P< 0.05;Figure 4F).

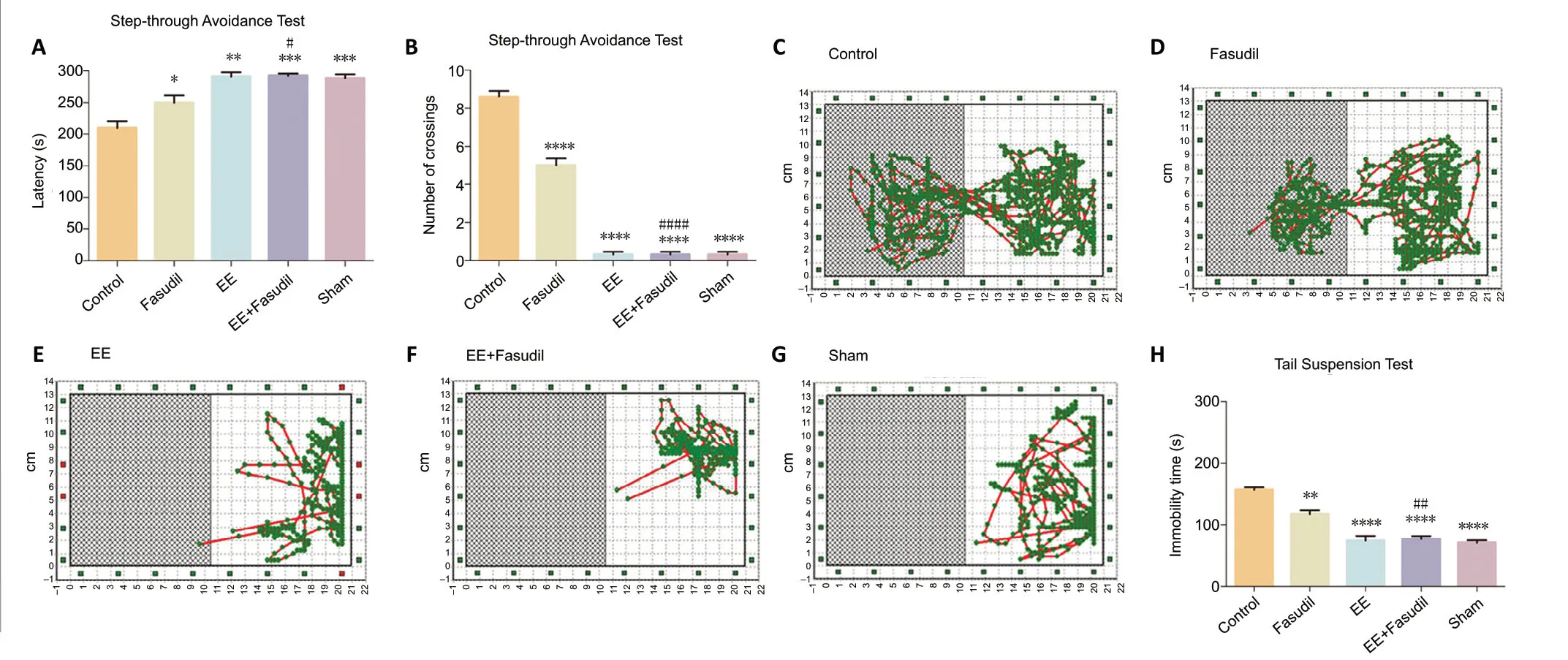

EE combined with fasudil treatment ameliorates memory deficits in stroke mice

A step-through passive avoidance test was performed to assess the cognitive functions, especially short-term memory,of animals (Kameyama et al., 1986). During the light-dark step-through task, mice were trained to remember an electric shock when they entered the dark compartment. After a photothrombotic stroke, the latency of entering the dark compartment was remarkedly reduced in the control group,while the number of times mice crossed through the door was increased compared with the sham group (P< 0.05),indicating learning and memory deficits (Figure 5AandB).After EE and/or fasudil intervention, the latency of entering the dark compartment was increased compared with the control mice (P< 0.05). Compared with the control group, the numbers of times mice crossed through the door in the EE,fasudil, and EE + fasudil groups were significantly decreased(P< 0.05). The EE + fasudil group showed a longer latency and crossed through the door fewer times than the fasudil group (P< 0.05). The travel pattern revealed that the mice in the EE condition preferred to stay in the light room compared with the control animals, similar to the sham group (P< 0.05;Figure 5C–G).

Figure 4|Effect of EE combined with fasudil treatment on the F-actin distribution in the hippocampal CA1 region of stroke mice.

Figure 5|Efefct of EE combined with fasudil treatment on the behavioral function of stroke mice.

EE combined with fasudil attenuates depression-like behavior in stroke mice

The immobility time in the tail suspension tests was calculated to assess depression-like behavior (Can et al., 2012). Strikingly,mice in the EE and EE + fasudil groups showed less immobility time than those in the control group (P< 0.05;Figure 5H),which indicates that EE was sufficient to attenuate depressionlike behaviors. Fasudil treatment decreased the poststroke depression-like behavior of mice (P< 0.05) compared with the control group, but the effect did not reach the level of that in the EE + fasudil group (P< 0.05;Figure 5H).

Discussion

Poststroke cognitive impairment is one of the most common complications in patients with ischemic stroke. The findings of this study provided evidence for the innovative role of both EE and fasudil treatment in cognitive rehabilitation. The behavioral, morphological, and immunofluorescence analysis results demonstrated that the combination of EE and fasudil treatment achieved better results than using either alone. This study increased the understanding of the function of both EE and fasudil in poststroke cognitive recovery.

In this study, the photothrombotic model was chosen to induce focal ischemia to standardize stroke severity. In a previous study, neuronal loss combined with a progressive decrease in F-actin in the hippocampal CA1 subfield was observed in a rodent model of global cerebral ischemia (Guo et al., 2019). Recent findings revealed a time-delayed (24-hour post-stroke) induction of cofilin-actin bundles, and their formation was found to extend into the nonischemic territory(Won et al., 2018). Similar results were shown in the present study; on the 21stday after the photothrombotic stroke in the cortex, mice showed a behavior pattern indicating cognitive impairment in the step-through avoidance test, along with an increase in cofilin phosphorylation and a downstream decrease in F-actin in the hippocampal CA1 subfield. In other words, the photothrombotic stroke caused distant damage to other nonischemic areas. In this study, neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 subfield was reduced and the density of F-actin was increased after either monotherapy or combination therapy with EE and fasudil. These results were consistent with those of previous fluorescein isothiocyanatelabeled phalloidin staining findings in which fasudil reversed weakening of the fluorescent intensity of actin buds (Xiao et al., 2014).

The tail suspension test was performed to eliminate emotionrelated behavior. The phenomenon that the animals preferred to stay in the light compartment after being housed in the EE condition may have two possible explanations. Poststroke depression-like behavior might reduce movement, while the recovery of short-term memory might benefit the stepthrough avoidance results. After the rehabilitation procedures,depression-like behavior was reduced. The tail suspension test result eliminated the bias favoring depression-like behavior,which indicates that the reduction in the scope of travel patterns was more likely related to the memory of the electric shock than to poststroke depression.

A previous study on a ROCK2 knockout mouse model provided plausible evidence that Rho/ROCK2 signaling was critical for synaptic function through alteration of cofilin and actin (Zhou et al., 2009). A further pharmacological experiment showed that downstream LIMK activity was required for memory acquisition and reconsolidation (Lunardi et al., 2018). Cofilin, a potent actin-binding protein and a downstream factor of LIMK,severs and depolymerizes actin filaments during an ischemic stroke (Alhadidi et al., 2016). In this study, the alteration of p-cofilin expression was consistent with the rearrangement of F-actin. As shown in the western blot analysis and phalloidin staining, phosphorylation of cofilin was inhibited by fasudil administration, and F-actin density was increased. The data in this study were consistent with previous findings that the ROCK inhibitor fasudil provided robust neuroprotection of brain tissue by depressing actin turnover (Gisselsson et al.,2010). Moreover, fasudil-treated animals housed in the EE condition had a higher F-actin puncta density and neuron number in the ipsilateral CA1 region than those housed in a standard cage or normal saline-treated animals housed under the EE condition. This finding indicated a synergy between the ROCK inhibitor and enriched housing stimulation; however,the underlying mechanism still remains unknown.

Furthermore, the trends of the behavioral and morphological results were different, which indicates that a more complicated mechanism is involved in short-term memory.The behavioral tests showed that learning and short-term memory deficits were ameliorated by suppression of ROCK signaling. The effect of housing under the EE condition was more significant than that of fasudil administration. However,in the subsequent morphological and immunofluorescence analyses performed to determine the ROCK signaling levels in the hippocampus, EE housing had a less significant effect than fasudil administration. This might have occurred because the step-through passive avoidance test focused on shortterm memory, which might involve both hippocampal actin remodeling and other plasticity mechanisms. As EE has been demonstrated to preserve memory after brain injury (Stuart et al., 2019), numerous studies have revealed an improvement in synaptic plasticity (Bayat et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019),oxidative state modulation (Pereira et al., 2009), and endogenous neuroprotection via adjustment of brain histone acetylation levels and neuroprotection-related transcription factors to normalize memory deficits after ischemia (Sun et al., 2010). Therefore, in addition to the fasudil-related ROCK2 inhibition of behavioral changes, EE might be effective in improving short-term memory.

In summary, hippocampal ROCK2/cofilin signaling is involved in poststroke cognitive recovery. EE and fasudil treatment both could improve hippocampus-related memory and promote hippocampal puncta increases through modulation of ROCK2/cofilin signaling. Furthermore, compared with monotherapy,the combination of EE and the ROCK inhibitor fasudil resulted in improved cognitive results after photothrombotic stroke in a rodent model. These findings provide insight into an actin cytoskeleton-related rehabilitation strategy for treatment of cognitive deficits. However, this study had some limitations.The investigation was conducted only 21 days after stroke;hence, continuous changes in the hippocampus that occurred in previous stages are poorly understood. Additionally,changes in actin filaments were only examined in the CA1 region; therefore, future studies should be performed to examine changes in actin in other hippocampal regions and at additional time points (e.g., 3, 7, and 14 days after stroke).

Author contributions:Study design: GJX, QZ, SYL, KWY, HYX, YW;study performance: GJX, SYL, YTZ, CJW; data analysis and manuscript writing: GJX, QZ, HYX, YW. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Financial support:The study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 81672242, 81972141(both to YW); Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty of China, No.shslczdzk02702 (to YW); and Shanghai Special Support Plan for High-Level Talents, Yang Fan Funds of China, No. 20YF1403500 (to QZ). The funders had no roles in the study design, conduction of experiment, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement:This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Fudan University (approval No. 2019-huashan hospital JS-139) on February 20, 2019.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement:Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewer:Melanie G. Urbanchek, University of Michigan, USA.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its related enzymes and receptors play important roles after hypoxic-ischemic brain damage

- Regulation of neuronal bioenergetics as a therapeutic strategy in neurodegenerative diseases

- The secretome of endothelial progenitor cells:a potential therapeutic strategy for ischemic stroke

- The neuroimaging of neurodegenerative and vascular disease in the secondary prevention of cognitive decline

- Induced pluripotent stem cell technology for spinal cord injury: a promising alternative therapy

- The interaction of stem cells and vascularity in peripheral nerve regeneration