Regulation of neuronal bioenergetics as a therapeutic strategy in neurodegenerative diseases

Isaac G. Onyango, James P. Bennett, Jr, Gorazd B. Stokin

Abstract Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are a heterogeneous group of debilitating disorders with multifactorial etiologies and pathogeneses that manifest distinct molecular mechanisms and clinical manifestations with abnormal protein dynamics and impaired bioenergetics. Mitochondrial dysfunction is emerging as an important feature in the etiopathogenesis of these age-related neurodegenerative diseases. The prevalence and incidence of these diseases is on the rise with the increasing global population and average lifespan. Although many therapeutic approaches have been tested, there are currently no effective treatment routes for the prevention or cure of these diseases. We present the current status of our knowledge and understanding of the involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction in these diseases and highlight recent advances in novel therapeutic strategies targeting neuronal bioenergetics as potential approach for treating these diseases.

Key Words: aging; Alzheimer’s disease; amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; Huntington’s disease; mitochondrial biogenesis; mitochondrial dysfunction; mtDNA mutations;neurodegeneration; oxidative stress; Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Huntington’s disease (HD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are a heterogeneous group of progressively and irreversibly debilitating disorders with multifactorial etiologies and pathogeneses that manifest distinct molecular and clinical characteristics with impaired bioenergetics and abnormal protein dynamics (Yan et al., 2020). Mitochondrial dysfunction has emerged as an important feature in the etiopathogenesis of these age-related neurodegenerative diseases (Wang et al.,2019b).

As aging is the primary risk factor for most neurodegenerative disease (Mattson and Arumugam, 2018; Hou et al., 2019), the prevalence and incidence of these diseases continues to rise with the increasing global population and average lifespan(Erkkinen et al., 2018). Currently, no neurodegenerative disease is curable, and the treatments available only manage the symptoms or at best slow the progression of disease. With the global aging population expected to double by 2050 to 2 billion people (World Health Organisation, 2018), there is an urgent need for effective therapeutic approaches that are amenable of improving clinical course and outcome of these conditions to a significant extent.

Mitochondria are the energy powerhouses of the cell and generate ~90% of energy in the form of ATP by coupling the flux of electrons throughout the mitochondrial respiratory complexes I–IV with oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).

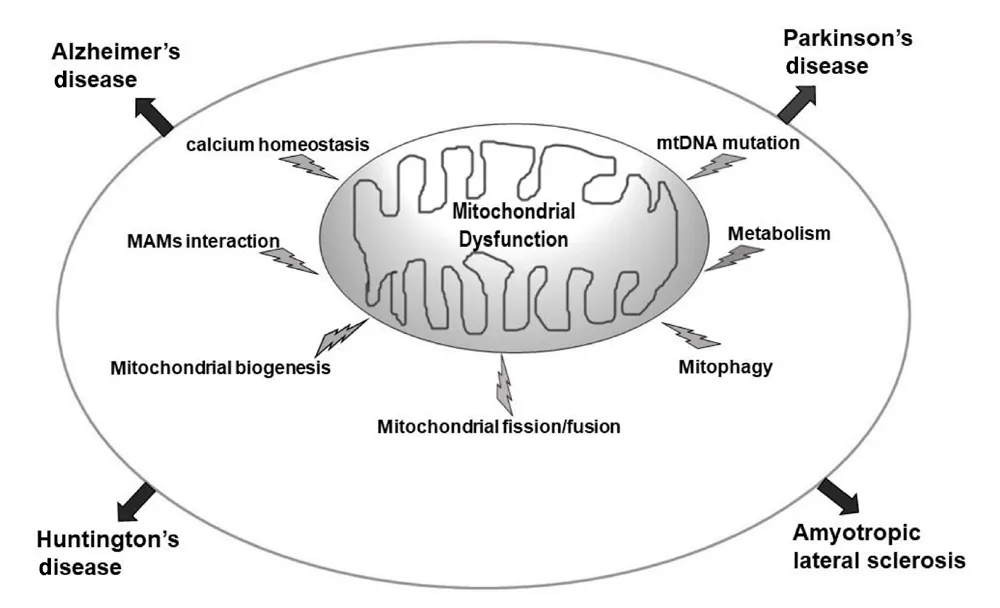

The brain, at less than 3% of whole body weight (Attwell and Laughlin, 2001), utilizes approximately 25% of the total glucose required by the body (Rossi et al., 2001). This is mainly because neurons depend on OXPHOS to support their functions, and more than 50% of this energy consumption is devoted to maintaining synaptic homeostasis and plasticity.Dysfunctional mitochondrial bioenergetics therefore lead to altered neurometabolic coupling, neural processing and circuitry, and functional connectivity in mature neurons(Uittenbogaard and Chiaramello, 2014). This very high energy demand makes neurons especially susceptible to bioenergetic deficits that may arise from mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition to energy production, mitochondria also tightly regulate calcium homeostasis by modulating calcium uptake in an energy-dependent and pulsatile manner via the mitochondrial calcium uniporter and by providing ATP to stimulate the plasma membrane calcium- ATPase,thereby influencing synaptic transmission, cellular survival and metabolism (Zenisek and Matthews, 2000; De Stefani et al., 2011; Rizzuto et al., 2012). Under pathological conditions,mitochondrial calcium overload compromises the integrity of the mitochondrial inner membrane, thereby triggering mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), a process when sustained results in cessation of ATP production, permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane, cytochrome c leakage and subsequent neuronal cell death (Dong et al.,2006; Pivovarova and Andrews, 2010). Additionally, the release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and peptides from the mitochondrial matrix can activate an immune response that promotes a pro-inflammatory cascade (Chandel,2015). The maintenance of an adequate and functional mitochondrial population during the lifetime of neurons is critical and involves a balance between mitochondrial biogenesis (Jornayvaz and Shulman, 2010; Golpich et al.,2017) , mitochondrial dynamics i.e. fusion and fission (Haun et al., 2013; Morciano et al., 2016), and mitophagy (de Castro et al., 2010; Ding and Yin, 2012; Stetler et al., 2013). These processes are often dysregulated in NDDs (Figure 1).

Figure 1|Mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in sporadic age-related NDDs.

AD, the most common NDD, is marked by progressive loss of memory, characterized by the increased presence of extraneuronal amyloid plaques derived from the proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein(APP) and intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles made from hyperphosphorylated tau protein in the brain. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a prominent early feature of AD with lower energy metabolism being one of the primary abnormalities in this disease (Sheng et al., 2012). Mitochondrial OXPHOS impairment is observed in AD brains (Hauptmann et al.,2009) with the most consistent defect being a deficiency in cytochrome c oxidase (COX, complex IV) (Kish et al., 1992;Cardoso et al., 2004). Dysfunction of COX increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, reduces energy stores, and disturbs energy metabolism (Mutisya et al., 1994).

The second most common NDD is PD, a progressive neurological movement disorder linked to uncertain etiology having possible effects of genetic and environmental factors (Tomiyama et al., 2008; Korecka et al., 2013). While the cellular mechanisms that result in cell death in the nigrostriatal system in PD are still unclear (Korecka et al.,2013), mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, aberrant protein folding, and abnormal protein aggregation are accepted as the main cause (Greenamyre and Hastings, 2004; Ortega-Arellano et al., 2011; Golpich et al., 2015). Complex I deficit is the most common underlying mitochondrial dysfunction observed in PD (Keeney et al.,2006; Ng et al., 2012; Golpich et al., 2015).

HD is a genetic disorder caused by trinucleotide repeat(CAG) expansions in thehuntingtingene that causes early degeneration of medium spiny neurons in the striatum,resulting in continuous involuntary motor movements.Striatal metabolism is decreased well before atrophy, and the progression of the disease is more strongly correlated with glucose hypometabolism than with the number of CAG repeats (Antonini et al., 1996; Ciarmiello et al., 2006;Civitarese et al., 2010). Mitochondrial dysfunction is strongly associated with the pathogenesis of HD (Quintanilla et al.,2008; Chaturvedi et al., 2009; Chiang et al., 2011) and ATP levels and electron transport chain (ETC) activity are reduced in patients with HD (Cho et al., 2010). In late stage patients with HD, decreased activity of several OXPHOS components,including mitochondrial complexes II, III, and IV is observed in striatal neurons (Reddy et al., 2009).

ALS is a progressive adult-onset NDD that is accompanied by ongoing loss of motor neurons of central nervous system,causing muscle atrophy, respiratory failure and progressive weakness. ALS is characterized by accumulation of mutant proteins (like SOD1, FUS, TDP43, and Sqstm1/p62) (Vicencio et al., 2020). The etiology of ALS is still not fully understood but mitochondrial dysfunction has been identified as an initial phenomenon (Cozzolino and Carri, 2012). The loss of mitochondrial function precedes onset of diseases, which has been indicated inin vivostudies of ALS disease model by occurrence of defects in OXPHOS, calcium buffering, and mitochondrial transport (Orsini et al., 2015). ALS patients are hypercatabolic and have increased energy expenditure at rest(Funalot et al., 2009). ALS patients are also glucose intolerant(Pradat et al., 2010) and insulin resistant (Reyes et al., 1984)and the oxidative stress that contributes to the pathogenic pathway in ALS derives from defective OXPHOS (Lee, 2009).

At the subcellular level mechanistic similarities among these diseases include: mutations in mtDNA, impaired bioenergetics,increased ROS production, and abnormal protein dynamics,including the mitochondrial accumulation of disease specific proteins, impaired axonal transport, and programmed cell death (Armstrong, 2007; Camandola and Mattson, 2017).Bioenergetic deficits strongly influence the initiation and progression of disease. [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging studies document glucose hypometabolism in brain regions affected in patients with AD,PD, ALS, and HD (Borghammer et al., 2010; Camandola and Mattson, 2017).

Given that bioenergetics deficits are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction including ETC deficiencies (Golpich et al., 2017): mitochondrial complex I, III, and COX deficiency in AD (Yamada et al., 2014), mitochondrial complex I and IV deficiency in PD (Hoglinger et al., 2003), mitochondrial complex II, III, and IV deficiency in HD (Fukui H and Moraes CT,2007), and mitochondrial complex I, II, III, and IV deficiency in ALS (Menzies et al., 2002), developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting neuronal bioenergetics is a viable approach for treating these diseases.

Database Search Strategy

We used keyword search on both PubMed and Google Scholar for articles with keywords mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases from 1999 to present.

Mitochondrial Genome

Unlike the nuclear genome which is only present in two copies in a post-mitotic cell, mtDNA is present in 10 s–1000 s of copies in each cell and undergoes lifelong replication in post-mitotic cells including neurons (Wei et al., 2017). The overall cellular content of mtDNA generally correlates with the underlying energy demand of the cell. The human mtDNA is circular and contains 16,569 base pairs and 37 genes. Of these genes, 22 encode transfer RNAs, two encode ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs; 12S and 16S), and the remaining 13 encode polypeptides. The 13 polypeptides encoded by mtDNA belong to the subunits of OXPHOS enzyme complexes I–V.Unlike nuclear DNA in which 98–99% is non-coding (Venter et al., 2001), most mtDNA genes are contiguous, generally separated by one or two non-coding base pairs, resulting in approximately 93% of mtDNA bases encoding proteins.Since germ cells have few mitochondria and are selectively degraded, the hereditary mode of most mitochondria is maternal inheritance, although biparental transmission of mtDNA in an autosomal dominant-like pattern has recently been demonstrated (Luo et al., 2018).

MtDNA Mutations

mtDNA do not have histone protection and are more likely to be exposed to ROS. Further, most of their entire coding regions lack repair mechanisms. As a result, mtDNA are highly susceptible to damage and mutations, with a 10- to 100-fold greater mutation rate than nuclear DNA (Stewart and Chinnery, 2015). The accumulation of mtDNA mutations impairs the electron transport chain (ETC), triggers oxidative damage, and generates ROS, resulting in bioenergetic deficits,dysregulated intracellular calcium levels (from calcium pump inactivation), activated and damaged membrane phospholipids and ultimately neurodegeneration (Reddy,2009; Cha et al., 2015).

Different versions of the mitochondrial genome can coexist in each cell, where unlike the maternally inherited germ line variants (which are ‘homoplasmic’), the somatic mutations are usually present alongside the original wild-type molecules(heteroplasmy). Since each cell contains thousands of copies of mtDNA, the proportion of mutants in any one cell changes over time (Naue et al., 2015; Duan et al., 2018). Having several copies of mtDNA allows each mitochondrion to function normally, even when some copies are mutated, allowing cells to carry high loads of mutant mitochondrial DNA before their function is affected and disease symptoms emerge only when the mutant load exceeds a specific threshold (Stewart and Larsson, 2014). This threshold is lower for certain cell types, such as postmitotic neurons, which depend highly on mitochondria due to their high-energy metabolism (Carelli and Chan, 2014) and lack the capacity to proliferate, as a means of mitigating the damage that accumulates. Indeed, mtDNA deletions accumulate in the aging brain, reaching higher levels in regions vulnerable to neurodegeneration (Bender et al., 2006;Ross et al., 2013). Genetic evidence that mtDNA mutations can institute AD, PD HD and ALS like changes comes from cybrid studies (Swerdlow et al., 1997; Flint Beal, 2000; Trimmer and Bennett, 2009; Ferreira et al., 2010). Extensive analysis of such cybrid cell lines has revealed that their bioenergetic function declines with increasing time in cell culture (Trimmer et al.,2004). Indeed both inherited and acquired mtDNA mutations contribute to neural aging and NDDs (Cha et al., 2015; Keogh and Chinnery, 2015) and abnormal amounts of mtDNA have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid and brains of patients with neurodegenerative diseases (Hauptmann et al., 2009;Sheng et al., 2012).

Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress can occur when production of ROS, as well as reactive nitrogen species (RNS), outpaces the neuron’s ability to inactivate ROS/RNS and to repair damage (Jodeiri Farshbaf et al., 2016).

Mitochondria convert between 0.4–4% of the total consumed oxygen into superoxide radicals as a by-product of OXPHOS via electron leakage from the respiratory chain (Pieczenik and Neustadt, 2007). ROS comprise superoxide radicals, H2O2, and hydroxyl radicals (Naudi et al., 2012) while RNS include the nitric oxide radical (NO?), the nitrogen dioxide radical (?NO2),nitrite (NO2–) and peroxynitrite (ONOO–). Mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase/thioredoxin/peroxiredoxin-3,5 system,glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione anti-oxidant system effectively scavenge these ROS (Drose and Brandt, 2012). ROS stimulate mild uncoupling of mitochondria, and the resulting increase in proton conductance can have a negative feedback effect on ROS production (Naudi et al., 2012). Furthermore,the MPT pore (MPTP) is opened to reduce the electrochemical gradient and accelerate oxygen consumption, which decreases ROS production. Cytochrome c is also a powerful ROS scavenger. The presence of low ROS concentrations is physiologically normal, and ROS function as important intracellular second messengers (Murphy et al., 2011).

However, excessive ROS generation is injurious to mtDNA and potentially leads to impaired ETC functions, reduced ATP synthesis, mitochondrial dysfunction, cell injury, and even apoptosis. ROS play key roles in the initiation and modulation of cell apoptosis (McCarroll et al., 2004). Similar to ROS, RNS are highly toxic (Bergendi, 1999). Microglia also play a role in generating RNS as nitric oxide synthases, inducible nitric oxide synthase and NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2), and NADPH oxidase (NOX) are induced in these glial cells (Saha and Pahan,2006). NOX2 activation can lead to a respiratory burst of superoxide flooding the mitochondria further contributing to neurodegeneration. NO? has been shown to play a role in neurodegenerative diseases by acting as a neurotoxin when excessively produced (Schulz et al., 1995).

Oxidative imbalance and resultant neuronal damage play a critical role in the initiation and progression of AD (Wang et al.,2014). The excessive accumulation of ROS in AD may induce mitochondrial dysfunction although the exact mechanisms underlying the disruption of redox balance still remain elusive(Zhao and Zhao, 2013). Aβ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction has been suggested to inhibit the efficient production of ATP and increase the generation of ROS in AD (Castellani et al.,2002; Zhao and Zhao, 2013). The activity of Complex I of the respiratory chain in SNc of patients with PD is reduced and may contribute to the generation of excessive ROS which in turn can induce apoptosis (Schapira, 2008; Blesa et al., 2015;Franco-Iborra et al., 2016). This mitochondrial Complex I deficiency is also present in the frontal cortex, fibroblasts, and blood platelets of PD patients (Blesa et al., 2015). Oxidative stress plays a crucial role in the neurodegenerative process of HD (Stack et al., 2008; Tasset et al., 2009). Indeed, susceptible neurons in the HD brain may not be able to handle well an increase in ROS/RNS production. Studies in transgenic mouse models of HD have shown an altered pattern of expression and activity of the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS) (Deckel,2001, 2002), as well as of the antioxidants SOD (Santamaria et al., 2001) and ascorbate (Rebec et al., 2002) in R6/1 and R6/2 HD transgenic mice (which express exon 1 of the human HD gene with 115 and 145 CAG repeats respectively (Mangiarini et al., 1996)). Furthermore, ROS production is also increased in the striatum of R6/1 mice (Perez-Severiano et al., 2004), while an increase in the levels of lipid peroxidation has recently been detected in several transgenic and knock-in HD mouse models (Lee et al., 2011). Free radical damage and abnormal free radical metabolism is evident in sporadic ALS and familial ALS patients (Pollari et al., 2014). The aberrant activity of mSOD1 leads to oxidative damage (Wiedau-Pazos et al.,1996; Crow et al., 1997) and other ALS-linked proteins, such as mutant TDP-43, promote oxidative stress in a motoneuron cell line (Duan et al., 2010). Excitotoxicity and oxidative stress caused by astrocytes arises from aberrant glutamate receptor function which leads to mis-regulated glutamate homeostasis(Rothstein et al., 1992).

Mitochondrial Dynamics

The movement, fusion and fission, remodeling of cristae,biogenesis and mitophagy constitute mitochondrial dynamics.These quality control processes are stringently regulated and adjusted to modify the overall mitochondrial morphology in response to changing energy demands and cellular stress(Eisner et al., 2018; Tilokani et al., 2018). Alteration in trafficking and fusion-fission dynamics in AD, PD, HD, and ALS has been shown (Kodavati et al., 2020).

Mitochondrial Fusion and Fission

Imbalances between mitochondrial fission and fusion have been proposed to cause neurodegenerative diseases; acute readjustment of such imbalances can have beneficial effects on mitochondrial structure and function and positively influence cell survival in various disease models (Chen and Chan, 2009; Itoh et al., 2013; Sebastián et al., 2017).Mitochondrial fusion is conserved in all eukaryotic cells and is essential for life (Chen et al., 2003). Fusion enables the transfer of mitochondrial components from viable mitochondria into those that are functioning at a suboptimal level thereby mitigating damage and ensuring the maintenance of an efficient homogeneous mitochondrial population (Youle and van der Bliek, 2012). When cells are stressed, stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfusion, prevents mitophagy, maintains OXPHOS and preserves mitochondrial integrity (Wai and Langer, 2016). During starvation, stressinduced mitochondrial hyperfusion maintains ATP levels and protects cells from apoptosis (Gomes et al., 2011).Conversely, fusion-deficient cells have reduced growth, widespread differences in ?ψm and reduced respiration (Chen et al., 2005). Thus, fusion of the mitochondrial network is cytoprotective, especially during stress (Neuspiel et al., 2005;Gomes et al., 2011), while the loss of fusion predisposes cells to apoptosis. Fusion occurs only between two partner mitochondria that have sufficient ?ψm, whereas those that are depolarised are fusion-deficient (Twig et al., 2008)ensuring that only biochemically functional mitochondria can fuse back with the network, while dysfunctional mitochondria are isolated and degraded. Mitochondrial outer membrane fusion is mediated by the mitofusin proteins Mfn1 and Mfn2, which form homo and heterodimers between the two opposing membranes (Koshiba et al., 2004). Mitochondrial inner membrane fusion is regulated by optic atrophy protein 1(OPA1). OPA1-depletion induces mitochondrial fragmentation(Cipolat et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2019). OPA1 also has roles in shaping the mitochondrial cristae junctions, which house the majority of ATP synthase, complex III and cytochrome c thus playing an important role in regulating OXPHOS and apoptosis(Olichon et al., 2003; Griparic et al., 2004; Cogliati et al.,2016).

The major mitochondrial fission protein is the mechanochemical GTPase dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1),which constantly cycles between the cytoplasm and the mitochondrial outer membrane (Wasiak et al., 2007). Fission is required to maintain mitochondrial function and integrity and in postmitotic cells such as neurons it plays an important role in transport and distribution of mitochondria to distal neurites (Li et al., 2004; Verstreken et al., 2005; Lewis et al.,2018). It is also crucial for quality control as elimination of damaged mitochondria by mitophagy via the PINK1/parkin pathway (Narendra et al., 2008, 2010; Ashrafi et al., 2014;Pickrell and Youle, 2015) involves mitochondrial fission (Tanaka et al., 2010; Kageyama et al., 2014).

The balance between mitochondrial fusion and fission is impaired in AD neurons (Zhu et al., 2018). The balance of mitochondrial fusion and fission is disrupted in several models of PD (Santos and Cardoso, 2012). In PD cytoplasmic hybrid(cybrid) cells there is a significantly increased proportion of mitochondria with swollen vacuoles, pale matrices and few remaining cristae (Castellani et al., 2002). In HD brain there is a significant increase in Drp1 and decrease in Mfn1 (Reddy,2014). This imbalance between the mitochondrial fusion and fission results in alterations of mitochondrial morphogenesis and negatively impacts important cellular mechanisms thus exacerbating neuronal death (Kim et al., 2010). Further,mutant HTT protein triggers mitochondrial fission prior to the emergence of neurological deficits and mutant HTT protein aggregates (Shirendeb et al., 2011, 2012; Reddy, 2014). ALS patients and animal models have altered mitochondrial dynamics with excessive fragmentation of mitochondria.Smaller mitochondria are observed in different models expressing ALS mutant SOD1 (Khalil and Liévens, 2017) and linked to a misexpression of mitochondrial dynamics genes.Mutant SOD1 mouse model spinal cord and skeletal muscles reveal downregulated Mfns (Liu et al., 2013; Russell et al.,2013) as well as OPA1, while levels of phosphorylated DRP1 and Fis1 are elevated (Liu et al., 2013). Inactivating DRP1 restores normal morphology of mitochondria and prevents death of mutant SOD1-expressing neurons (Song et al., 2013).

Mitochondrial Biogenesis

Increased mitochondrial biogenesis is a physiological response to stress conditions (e.g., cold, exercise, nutritional status),which is activated to meet the energetic requirements of tissues (Viscomi et al., 2015).

Mitochondrial biogenesis is essential for maintaining an adequate functional neuronal mitochondrial mass. It is a highly regulated process that requires coordination and crosstalk between the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes (Ryan and Hoogenraad, 2007) and occurs on a regular basis in healthy cells where mitochondria constantly divide and fuse with each other. Replication is regulated by the mtDNA polymerase γ (POLG) consisting of the catalytic subunit encoded by the POLG gene and auxiliary dimeric subunit encoded by the POLG2 gene (Graziewicz et al., 2006 ). mtDNA is transcribed by the mitochondrial RNA polymerase POLRMT (Tiranti et al., 1997). The key enhancer protein is TFAM (transcription factor A, mitochondrial), which ensures mtDNA unwinding and flexing required for the POLRMT binding to the mtDNA promoters. TFB2M (transcription factor B2, mitochondrial)acts as a specific dissociation factor that provides interaction between POLRMT and TFAM. Both TFB1M and TFB2M bind rRNA dimethyltransferases and, therefore, can function as rRNA modifiers (Rebelo et al., 2011). The major role of TFB1M is rRNA methylation and not its transcription factor function(Metodiev et al., 2009). Nuclear respiratory factors NRF1 and NRF2 regulate expression of the ETC subunits encoded by the nuclear genome (Evans and Scarpulla, 1990) and bind to the promoters of genes involved in mtDNA transcription. NRF1 binds to the specific promoter sites and regulates expression of TFAM (Virbasius and Scarpulla, 1994), TFB1M, and TFB2M(Gleyzer et al., 2005). Besides, nuclear respiratory factors, in particular NRF2, regulate expression of other mitochondrial enzymes, e.g., TOMM20 (translocase outer mitochondrial membrane), a key enzyme in the mitochondrial membrane transport (Blesa and Hernández-Yago, 2006). In turn, NRF1 and NRF2 are regulated by transcription coactivators,including PGC-1α (Scarpulla, 2008). PGC-1α is regulated on both the transcription and post-translation levels (Fernandez-Marcos and Auwerx, 2011). p38 MAPK is another factor that regulates the expression of PGC-1α by activating transcription factor 2 (Akimoto et al., 2005).

The impaired function of the master regulator for mitochondrial biogenesis PGC-1α has been recognized as a major contributor to the neuropathogenesis of several NDDs including AD, PD and HD (Tsunemi and La Spada,2012; Uittenbogaard and Chiaramello, 2014). Reduced mitochondrial number and impaired mitochondrial gene expression contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction associated with AD (Zhu et al., 2013). Morphometric analyses performed on hippocampal neurons of autoptic brains from patients with AD have revealed a significant decrease in intact mitochondria(Hirai et al., 2001). The decreased levels of PGC-1α imply abnormal mitochondrial biogenesis as a key event for reduction of mitochondrial mass and bioenergetic functions in AD brain (Qin et al., 2009). The network of transcription factors regulating mitochondrial biogenesis, including NRF-1,NRF-2 and TFAM, are also altered suggesting a deficiency in the process of mitochondrial biogenesis (Sheng et al., 2012).Abnormal PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis also interfaces with PD (Zheng et al., 2010; Shin et al., 2011).A meta-analysis of independent microarray analyses using microdissected human DA neurons from PD patients has documented a down-regulation of PGC-1α-regulated target genes, congruent with the concept of altered PGC-1α expression being the cause rather than the consequence of PD pathogenesis (Zheng et al., 2010).

In HD the severity of symptoms have been linked to sequence variants of PGC-1α (Chaturvedi et al., 2009; Weydt et al.,2009). PGC-1α dysfunction extends beyond the neuronal lineage to oligodendrocytes where PGC-1α regulates the expression of several genes required for proper myelination,such as myelin basic protein, in keeping with the observed deficient myelination in HD transgenic mice (Xiang et al.,2011). Finally, PGC-1α and its downstream effector NRF1 are downregulated in spinal cord and muscle tissues of patients and mutant SOD1 mice (Thau et al., 2012; Russell et al., 2013).Further, single-nucleotide polymorphisms reported in the brain-specific promoter region of PGC-1α modify age of onset and survival of ALS patients and mutant SOD1 mice (Eschbach et al., 2013).

Mitochondria Stress Response Signaling

Mitochondria produce most of the cellular ROS and the stress signaling that induces cellular senescence and apoptosis(Hamanaka and Chandel, 2010; Sena and Chandel, 2012).A major consequence of increased ROS and altered cellular redox state is the oxidation of thiol groups in cysteine residues in relevant proteins (Hamanaka and Chandel, 2010). FoxO transcription factors are activated in response to elevated ROS levels and induce anti-oxidant responses (increased expression of catalase and SOD2), cell cycle arrest and/or cell death (Kops et al., 2002; Fu and Tindall, 2008). Mitochondrial Akt, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), PKA, Abl, PKC,Src and Atm modulate the cellular stress response (Bera et al., 1995; Kumar et al., 2001; Majumder et al., 2001; Alto et al., 2002; Das et al., 2008; Robey and Hay, 2009; Mihaylova and Shaw, 2011). Akt phosphorylates and inactivates GSK-3β, which can localize to the mitochondria. Mitochondrial GSK-3β phosphorylates myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein (MCL-1) and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC)(Juhaszova et al., 2004; Maurer et al., 2006) leading to MCL-1 degradation and induction of apoptosis (Maurer et al., 2006).The phosphorylation of VDAC by GSK-3β results in increased mitochondrial membrane permeability which also leads to apoptosis (Juhaszova et al., 2004; Martel et al., 2013). GSK-3β can also phosphorylate and promote the proteasomal degradation of c-Myc, cyclin D1, and β-catenin (Rubinfeld et al., 1996; Diehl et al., 1998). Hypoxia and other physiological stresses can induce the translocation of PKA to mitochondria(Carlucci et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2011) causing it to bind through Rab32 and other A-kinase AKAPs (163) resulting in the phosphorylation of VDAC (164), Drp1 (Kim et al., 2011),and other mitochondrial proteins.

Hypoxia, by inducing SIAH2, a mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase, destabilizes AKAP121 and limits oxidative capacity under conditions of low oxygen. Interestingly, AKAP121 also appears to promote mitochondrial localization of Src-tyrosine kinase (Livigni et al., 2006) where Src appears to regulate COX activity and respiratory activity (Miyazaki et al., 2003;Livigni et al., 2006), and other mitochondrial substrates for Src family kinases are likely (Tibaldi et al., 2008). Increased ROS induces protein kinase C-delta (PKCδ) associated with the mitochondria and this in turn recruits other signaling molecules, including the Abl tyrosine kinase that is associated with loss of membrane potential and non-apoptotic cell death (Kumar et al., 2001). Impaired oxidative metabolism and decreased ATP levels in neurons activate AMPK (Maurer et al., 2006). AMPK can also be activated by drugs such as metformin that inhibits complex I or resveratrol that inhibits the F0F1 ATPase (Mihaylova and Shaw, 2011). AMPK modulates mitochondrial metabolism and targets Acetyl CoA carboxylase-2 to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM)where it regulates lipid metabolism by controlling production of malonyl CoA (Mihaylova and Shaw, 2011). AMPK therefore plays a key role in mitochondrial homeostasis by ensuring that only functionally viable mitochondria are retained. Upon its activation it induces not only mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of PGC-1α (Zong et al., 2002; J?ger et al.,2007) but also initiates mitophagy through ULK1 activation and mTOR inhibition (Egan et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011).

ATM kinase inhibition causes central nervous system neurodegeneration in animal models (Petersen et al., 2012).ATM kinase, is partly located at the mitochondria and is activated by mitochondrial uncoupling (Valentin-Vega et al.,2012). While the mitochondrial substrates of ATM are not known, loss of ATM in genetically engineered mouse models leads to mitochondrial dysfunction. ATM signaling is reduced in the neurons in vulnerable regions of the AD brain (Shen et al., 2016). A recent study of a mouse model of familial AD showed that the mutant amyloid precursor protein (APP)transgene caused aberrant persistence of gH2AX in the brain(Gleyzer et al., 2005). ATM is also involved in the pathogenesis of PD because ATM gene knockout (ATM KO) mice exhibit severe loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive DA nigro-striatal neurons, and midbrain DA neurons progressively degenerate with age (Eilam et al., 2003). PARK2 and ATM mutations sometimes occur synchronically at the same amino-acid residue, causing neuronal degeneration (Veeriah et al., 2010).ATM deficient neurons re-enter the cell cycle and die (Yang and Herrup, 2005; Rimkus et al., 2008), suggesting that ATM may protect neuron by stopping cells re-entering the cell cycle and lessening DNA damage. ATM impairment in glial cells may also trigger innate immune responses leading to cause neurodegeneration (Petersen et al., 2012). The histology of microglial cell in ATM KO mice is abnormal, and astrocytes from ATM KO mice show significant expressions of oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress and a senescence-like reaction (Kuljis et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2005). ATM deficiency may disturb DNA repair, trigger apoptosis, and accelerate aging and neuroinflammation. In HD, cells transfected with mutant HTT protein fragments showed elevated DNA damage and ATM activation (Giuliano et al., 2003; Illuzzi et al., 2009),and increased gH2AX was also found in fibro blasts from HD patients (Giuliano et al., 2003) and in HD mouse and patient striatal neurons (Enokido et al., 2010). Intriguingly, HD patient cells exhibit radiosensitivity, albeit less than A-T cells,suggesting subtle dysfunction in the DNA damage response(Ferlazzo et al., 2014).

Mitochondria and Inflammation

The local sterile inflammation has been shown to be finely linked with the development and the progression of different NDDs including AD, PD and ALS (Lin and Beal,2006). Neuroinflammation is commonly driven through the abnormal activation of microglia and astrocytes, by damageassociated molecular patterns (DAMPs) molecules released from damaged and necrotic cells (Yin et al., 2016; Wilkins et al., 2017). Dysregulated activation of microglia and astrocytes results in persistent inflammasome activation, which, together with an increased level of DAMPs, leads to the establishment of low-grade chronic inflammation and thus to the development of age-related pathological processes (Kapetanovic et al.,2015). Noticeably, neuroinflammation drives the increased secretion of cytokines and chemokines not only within the brain, but also systemically (Licastro et al., 2000) and, in some cases, might lead to blood-brain barrier disruption with the consequent infiltration of peripheral immune cells (Wilkins et al., 2017). At the molecular level, neuroinflammation is mainly triggered by redox status (Innamorato et al., 2009): ROS are produced by microglia upon their activation by intrinsic or extrinsic factors [reviewed in Kierdorf and Prinz (2013)] and are released in the extracellular space. Uncontrolled ROS production might affect intracellular redox balance, thus inducing the expression of proinflammatory genes by acting as second messengers (Rojo et al., 2014). Consequently,abnormal activation of microglia leads to the release of reactive oxygen intermediates, proinflammatory cytokines,complement proteins and proteinases, driving a chronic inflammatory state responsible for triggering or maintaining neurodegenerative processes (Dheen et al., 2007). The main players involved in these processes are mitochondria, which not only generate ROS but also respond to ROS-induced cellular changes (Handy and Loscalzo, 2012).

Mitochondrial dysfunction can be both the leading cause of neuroinflammation and can be induced by it. Damaged mitochondria trigger the process of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization that initiates both apoptosis and necrosis.Adult neurons are resistant to apoptosis (Yuan et al., 2019).Necroptosis, a form of regulated necrotic cell death induced by tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), is highly activated in NDDs (Ito et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2019). Briefly, necroptosis is a form of programed cell death coordinated by receptor-interacting kinases 1 (RIPK1) and RIPK3 and mixed lineage kinase domainlike protein under caspase-8 deficient conditions. Necroptosis can be stimulated by TNF, other members of the TNF death ligand family, interferons, Toll-like receptor signaling and viral infection (Zhang et al., 2017). Ultimately, accumulation of damaged mitochondria can activate NLRP3 inflammasomedependent inflammation in microglia. Moreover, damaged neurons are responsible for releasing DAMPs, such as mtDNA,in the extracellular environment, eliciting local inflammation(Nakahira et al., 2011) by increasing inflammasome activation,and thus IL-1β secretion, and also binding to microglial toll-like receptor-9, inducing TNFα and nitric oxide (NO) production(Iliev et al., 2004).

Mitochondrial Calcium Dyshomeostasis

Mitochondria actively regulate intracellular calcium levels; and when matrix calcium increases beyond physiological demands,the MPT pore (MPTP) opens, resulting in apoptotic or necrotic cell death (Rasola and Bernardi, 2011). The pathophysiological implications of altered calcium homeostasis has been described in AD (Yu et al., 2009), PD (Surmeier, 2007), HD(Bezprozvanny and Hayden, 2004) and ALS (von Lewinski and Keller, 2005). The common thread in these NDDs is that MPTP opening and altered calcium handling are involved (Lin and Beal, 2006; Wojda et al., 2008; Abramov et al., 2017)and precede neuronal death (Calì et al., 2012). In AD, the Aβ peptide is translocated to the mitochondria via the TOM(translocase of the outer membrane) machinery, where it localizes to the mitochondrial matrix and interacts with specific intra-mitochondrial proteins (Hansson Petersen et al.,2008) and impairs the activity of respiratory chain complexes III and IV (Caspersen et al., 2005). Aβ peptide can also induce calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resulting in mitochondrial calcium overload (Ferreiro et al., 2008; Sanz-Blasco et al., 2008) leading to MPTP opening and cell death (Du et al., 2008). In PD, α-synuclein plays a similar role in inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death. α-synuclein localizes in the mitochondria (Nakamura et al., 2008; Di Maio et al.,2016) and inhibits complex I activity (Luth et al., 2014) leading to dose-dependent loss of mitochondrial membrane potential with an associated decrease in phosphorylation capacity(Banerjee et al., 2010).

Mutant, but not wild-type, huntingtin can interact with the outer mitochondrial membrane and significantly increase the susceptibility of mitochondria to calcium-induced MPTP opening.Mutant huntingtin induces mitochondrial swelling, MPTP opening, release of cytochrome c and subsequent activation of the apoptotic cascade. All these events were completely inhibited by CsA, indicating a role for calcium and MPTP opening in the pathogenesis of this disease (Choo et al., 2004).In ALS, the mutant SOD1 protein impairs mitochondrial functions by aggregating in the mitochondria and binding to the Bcl-2 protein thereby reducing its anti-apoptotic properties (Pasinelli et al., 2004 ), and impairing the activity of complexes I, II and IV of the respiratory chain (Jung et al.,2002). Motoneurons expressing mutant SOD1 showed an early increase in mitochondrial calcium with loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial swelling and ER overload,followed by an increase in cytosolic calcium (Tradewell et al.,2011).

Mitophagy

Mitophagy is the selective degradation of mitochondria by autophagy. Mitophagy can effectively remove damaged or stressed mitochondria, which is essential for cellular health(Wang et al., 2019a).

An excess of ROS may function as an autophagy trigger (Kurz et al., 2007) and dysfunctional mitochondria that overproduce ROS, are indeed selectively targeted for mitophagy (Lemasters,2005). Central to mitochondrial and cellular homeostasis,mitophagy is modulated by the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin pathway (Narendra and Youle, 2011)which primarily targets mitochondria devoid of membrane potential (ΔΨm). PINK1 accumulates on the outer membrane of dysfunctional mitochondria and recruit the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin (Valente et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2010; Narendra et al., 2010) that ubiquitinates several OMM proteins that are consequently targeted by P62/SQSTM1 (Geisler et al.,2010). F-box-containing proteins, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1, and WD40 domain protein 7 (FBXW7) have been identified as the critical regulators in the PINK/Parkin pathway of mitophagy (Rasola and Bernardi,2011). p62 recognizes ubiquitinated substrates and directly interacts with autophagosome-associated LC3 to recruit autophagosomal membranes to the mitochondria (Pankiv et al., 2007). Damaged mitochondria can also, independently of Parkin, increase FUNDC1 and Nix expression to recruit autophagosomes to mitochondria via direct interaction with LC3 (Novak et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2012). Ubiquitin ligases, like Smurf1, target depolarized mitochondria for mitophagy (Ding and Yin, 2012; Lokireddy et al., 2012; Fu et al., 2013). The transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2(Nrf2) partly regulates p62 expression due to the presence of an antioxidant response element in its promoter region (Ishii et al., 2000; Jain et al., 2010). Electrophilic natural products such as isothiocyanate compound, sulforaphane which upregulate Nrf2 by interfering with its regulator protein, the redox sensitive ubiquitination facilitator Keap1 (Kelch-like ECHassociated protein 1) can potentially induce p62 expression(Kensler et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2011). p62-mediated mitophagy inducer (PMI) (HB229), was recently developed to upregulate P62 via stabilization of Nrf2 and promote mitophagy. This compound bypasses the upstream steps of the mitophagic cascade and acts independently of the ΔΨm collapse, and does not mediate any apparent toxic effects on mouse embryonic fibroblast cells at the concentrations used in the assays (East et al., 2014). Parkin also modulates transport of mitochondria along microtubules to a perinuclear region where autophagosomes are concentrated (Narendra et al., 2010; Vives-Bauza et al., 2010). This is likely due to Parkinmediated turnover of Miro, a protein required to tether kinesin motor protein complexes to the OMM (Wang et al.,2011). HDAC6, a ubiquitin-binding protein deacetylase is also recruited to mitochondria by Parkin (Cho et al., 2009) along microtubules (Lee et al., 2010a, b). Mitophagy is crucial for cellular homeostasis and its impairment is linked to several neurodegenerative diseases (de Castro et al., 2010; Karbowski and Neutzner, 2012). However, selective pharmacologic modulators of mitophagy that would facilitate dissection of the molecular steps involved in the removal of mitochondria from the network via this pathway are not presently available.

The development of AD is closely correlated with mitochondrial autophagy defects [219, 220] and Parkin plays a key role in the removal of mitochondria. Parkin overexpression alleviates symptoms of AD (Ye et al., 2015). Supporting a role of mitophagy in AD, amyloid beta-derived diffusible ligands can induce the fragmentation of mitochondria and mitophagy(Wang et al., 2009; Nakamura et al., 2010). Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 is also one of the risk factors for sporadic PD (Rasola and Bernardi, 2011), and mitophagy thus may represent a common mechanism linking sporadic and familial PD (Bezprozvanny and Hayden, 2004;Surmeier, 2007; Yu et al., 2009). Mutation in the F-box domain is reported to be associated with the early-onset autosomal recessive PD. FBXW7 is involved in maintaining mitochondria and inducing mitophagy through direct interaction with Parkin, further confirming the significance of mitophagy in the pathogenesis of PD (von Lewinski and Keller, 2005).

Mitophagy is also altered in HD, and the mutant huntingtin induces selective autophagy (Khalil et al., 2015) and in cell culture models of HD, excessive mitochondrial fission partially mediates cytotoxicity (Guo et al., 2013). In addition,mutant Huntingtin is found to cause formation of spherical mitochondria in a nonapoptotic state, and it can also repress mitophagy, resulting in the impaired mitochondrial clearance(Rasola and Bernardi, 2011). In ALS, the reduced targeting of ubiquitinated mitochondria to autophagosomes may contribute to the disease pathogenesis (Benatar, 2007). In ALS models, the accumulation of damaged mitochondria can be detected by live cell imaging. Mitochondrial homeostasis can be reconstituted by inhibiting OPTN or TBK1 mutations,as well as pharmacological inhibition or genetic knockdown of PINK1 or Parkin. Altering TBK1/OPTN can significantly improve neuronal function and block disease progression. These data support the potential role of mitochondrial autophagy in ALS(Caspersen et al., 2005; Hansson Petersen et al., 2008; Calì et al., 2012).

Potential Interventions to Restore or Enhance mitochondrial Function in NDDs

We conclude with potential mitochondria-targeted therapies that may be beneficial for these age-related NDDs.

Genetic therapies

Mitochondrial-targeted transcription activator-like effector nucleases (mitoTALENs) can correct mtDNA mutations in cultured human cells from patients with a mtDNA disease(Bacman et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2018) and correct induced mtDNA mutationin vivoin mouse models (Bacman et al., 2018). Mitochondrially targeted zinc-finger nucleases(mtZNFs)(Gammage et al., 2014) are another tool for specific removal of mtDNA mutations with a relatively low risk for interaction with the cell’s nuclear DNA. myZNFs are able to remove a pathogenic mtDNA mutationin vivomouse experiment (Gammage et al., 2018). Almost all adult cells are heteroplasmic for mtDNA due to age-related acquired mtDNA mutations. The degree of mtDNA mutation load determines the onset of clinical symptoms, a phenomenon known as the threshold effect (Craven et al., 2017). Clinical symptomatology can be alleviated by shifting the existing equilibrium between healthy and mutated mtDNA in different ways (Rai et al.,2018). This is appealing for human clinical applications because it avoids the use of gene-editing techniques which might erroneously disrupt the function of normal genes of the treated cells (Gammage et al., 2014, 2018; Bacman et al.,2018; Peeva et al., 2018; Pereira et al., 2018).

Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants

Targeting detrimental neuronal ROS at the production stage without affecting ROS signaling would be ideal in preventing and treating AD. In this regard, it has been shown that mitochondria-targeted antioxidants potently sequester reactive oxygen intermediates and confer greater protection against oxidative damage in the mitochondria than untargeted cellular antioxidants. These mitochondria-targeted antioxidants such as (10-(6′-plastoquinonyl) decyltriphenylphosphonium) (SkQ1), MitoQ, MitoTEMPOL and MitoVitE prevent apoptosis by mitigating the oxidative damage more effectively than untargeted antioxidants such as 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox)(Oyewole and Birch-Machin, 2015). Other such antioxidants include: 4,5-dihydroxybenzene-1,3-disulfonate (Tiron), which has been engineered to accumulate within the mitochondria by permeabilizing the mitochondrial membrane (Fang et al., 2012) and astaxanthin, a mitochondrion-permeable antioxidant, that can penetrate the blood-brain barrier and is effective in preventing and treating macular degeneration(Piermarocchi et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014).

Antioxidants can also be targeted to mitochondria through the use of small, aromatic-cationic sequence motif called Szeto-Schiller (SS) tetrapeptides which enables them to be delivered and localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane with an approximate 1000–5000-fold accumulation (Smith and Murphy, 2011; Jin et al., 2014). Novel XJB peptides which consist of an electron and ROS scavenger (4-NH2-TEMPO) conjugated to the Leo-D-Phe-Pro-Val-Orn fragment of gramicidin S have been invented. This pentapeptide fragment can specifically target the XJB peptides to mitochondria.One of these peptides, XJB-5-131, improved mitochondrial function and enhanced the survival of neurons in a mouse model of HD (Xun et al., 2012). Another approach of targeting mitochondria with small bioactive molecules involves polymer based nano-carriers. These include biodegradable polylactide-co-gylcolide (PLGA) like PLGA CoQ10 nanoparticles(Nehilla et al., 2008) although their biological effects are yet to be fully elucidated.

N-Acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine (Melatonin), which is synthesized from tryptophan provides remarkable protection against oxidative stress in the brain and at physiological concentrations is more potent than vitamins C and E (Reiter et al., 1997, 1999, 2014; Galano et al., 2011). Melatonin and its metabolites function as broad-spectrum antioxidants (Tan et al., 2001, 2002; Ressmeyer et al., 2003). Melatonin also down regulates caspase-3 levels (Espino et al., 2010), which are linked directly to neuronal death (Louneva et al., 2008).

Enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis

The human mitochondrial genome can be manipulated from outside the cell to change expression and enhance mitochondrial energy production. TFAM has been engineered to rapidly pass through cell membranes and target mitochondria. Recombinant-human TFAM acts on cultured cells carrying a mtDNA disease (Iyer et al., 2012) as well as lab mice, energizing the DNA of the mice’s mitochondria,improving the memory of aged mice (Iyer et al., 2009;Thomas et al., 2012) and enabling them to run two times longer on their rotating rods than a control group cohort(Thomas et al., 2012). Expression of human TFAM significantly improved cognitive function, reducing accumulation of both 8-oxoguanine, an oxidized form of guanine, in mtDNA and intracellular Aβ in 3xTg-AD mice and increased expression of transthyretin, known to inhibit Aβ aggregation (Oka et al.,2016).

Calorie restriction to induce mitochondrial biogenesis

Calorie restriction (CR), i.e. the limitation of ingested calories without malnutrition, is known to enhance animal life span and prevent age-related diseases, including neurological deficits, brain atrophy, and cognitive decline (Colman et al.,2014). CR induces mitochondrial biogenesis (Cerqueira et al.,2012) in a NO?-mediated manner that culminates in increased mitophagy and the production of new, more efficient mitochondria that have reduced membrane potential,produce less ROS, consume increased levels of oxygen and exhibit an improved ATP/ROS ratio, leading to decreased energy expenditure (Onyango et al., 2010). In particular, the tissue-specific effects of CR include the prevention of the age-related loss of mtDNA in rat liver (Cassano et al., 2006)and the partial preservation of TFAM binding to mtDNA in rat brain with enhanced reserve respiratory capacity and improved survival in neurons (Picca et al., 2013).

Inducing mitophagy

Focal mitophagy eradicates degraded mitochondria and decreases ROS-induced neuronal death (Kubli and Gustafsson,2012). Regulators of PINK1/parkin, metformin, and resveratrol have also been shown to increase mitophagy (Wang et al.,2019a). Sirtuin activating compounds or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) precursors such nicotinamide riboside(NR) or nicotinamide mononucleotide also induce mitophagy via sirtuins (Song et al., 2015). A novel potential inducer of mitophagy, PMI (P62-mediated mitophagy inducer), acts independently of the PINK1/parkin pathway, and therefore does not affect the mitochondrial network or cause loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (East et al., 2014).

Inactive glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase(iGAPDH) can also induce mitophagy. It follows that iGAPDH serves as a molecular sensor for detecting and tagging damaged mitochondria as GAPDH is inactivated by mitochondrial ROS. Mitochondria-associated iGAPDH promotes direct uptake of damaged mitochondria into a lysosomal-like structure, a hybrid organelle of late endosome and lysosome (Yogalingam et al., 2013). Exogenously expressed, catalytically dead iGAPDH is sufficient to induce lysosomal-like structures to engulf damaged mitochondria for degradation (Yogalingam et al., 2013). Removing damaged or excessively ROS-producing mitochondria by modulating mitochondrial GAPDH may be key in protecting cells from damage.

Mild mitochondrial uncoupling

The pharmacological mitochondrial uncoupler 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) at low doses stimulates adaptive cellular stress-response signaling pathways in neurons including those involving brain-derived neurotrophic factor,the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein, and autophagy. Preclinical data show that low doses of DNP protects neurons and improves functional outcome in animal models of NDD (Geisler et al., 2017). The molecular reprogramming induced by DNP, which is similar to exercise and fasting is associated with improved learning and memory,suggesting potential therapeutic applications for DNP (Wei et al., 2015)

Enhancing proteasome function

Proteasome activation by small molecules is a promising strategy to treat or prevent NDDs characterized by the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates (Lee et al., 2010;Dantuma and Bott, 2014; Myeku et al., 2016).

Betulinic acid is a small molecule capable of increasing proteasome activity. It is a triterpene natural product that selectively enhances the chymotryptic-like site of proteasome activity. Synthetic modifications yielded inhibitory analogs,suggesting a complex structure activity relationship (Huang et al., 2007).

Another small molecule activator of the proteasome is Pyrazolone (Lee et al., 2010). It shows significant disease attenuationin vivomodels of ALS (Trippier et al., 2014) and while affinity pull down experiments verify its association with the proteasome, the mechanism of its regulation is still unclear. PD169316 a small molecule p38 MAPK inhibitor very potently activates proteasome activity and enhances Proteolysis Targeting Chimeric (PROTAC)-mediated and ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation and decreasing the levels of both overexpressed and endogenous α-synuclein in a bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay (Outeiro et al., 2008). It does this without affecting the overall protein turnover while increasing the viability of cells overexpressing toxic α-synuclein assemblies (Leestemaker et al., 2017).

Synthetic peptides based upon the HbYX motif are the most common class of proteasome gate openers. Activity of these vary greatly depending on which protein activator protein they are modeled after, yet several have been reported to increase turnover of oxidized (Lau and Dunn, 2018; Jones and Tepe, 2019) proteins (Gillette and et al., 2008; Dal Vechio et al., 2014).

Finally, proteasome activity can be enhanced through activation of the transcription factor (Nuclear factor(erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2)). The antioxidant 3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione (D3T) upregulates both 20S and 19S proteasome subunits, resulting in an increase in proteasome activity (Kwak et al., 2003). As a proof of concept, it has been shown that proteasome activation by genetic manipulation ameliorates the aging process and increases lifespan in different models includingC. elegans, human fibroblasts and yeast cells (Chondrogianni et al., 2015).

Inhibiting excessive mitochondrial fission

Mitochondrial fission is mediated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), a large GTPase, that is recruited to the OMM from the cytosol by several mitochondrial outer membrane protein adaptors, including fission 1 (Fis1), mitochondrial fission factor (Mff), as well as mitochondrial dynamics protein (MiD)MiD49 and MiD51 (Palmer et al., 2011, 2013; Loson et al.,2013). Mitochondrial fragmentation (a pathological process) is caused by excessive mitochondrial fission and/or by impaired mitochondrial fusion (Knott et al., 2008; Chen and Chan,2009).

Inhibiting excessive Drp1/Fis1-mediated mitochondrial fission may restore mitochondrial function and therefore benefit AD patients. Mdivi-1 is a Drp1 inhibitor (Cassidy-Stone et al., 2008) and its effects on Aβ-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and AD-associated neuropathology in cultured neurons and APP/PS1 double-transgenic AD mice have been investigated (Joshi et al., 2017). The mdivi-1 treatment improves ATP production and cell viability. Its effectsin vivohave been tested in TgCRND8 mice, an amyloid precursor line (Veeriah et al., 2010). Primary neuronal cultures from TgCRND8 mice treated with mdivi-1 showed significantly reduced amount of fractured mitochondria and increased mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP output and improves behavior in the spontaneous alteration task in a Y-maze apparatus (Veeriah et al., 2010).

P110, a seven-amino acid peptide, which specifically inhibits Drp1/Fis1 interaction without affecting the interaction of Drp1 with its other adaptors, attenuates Aβ42-induced mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1. The mitochondrial structure and function remains intact in cultured neurons of cells expressing mutant amyloid precursor protein (KM670/671NL), and in five different AD patient-derived fibroblasts that are treated with P110. The advantage of P110 is that it inhibits excessive mitochondrial fission in all tissues where excessive fission occurs without altering basal (physiological) fission even when used long termin vivo(Joshi et al., 2017).

Restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential

For more than three decades ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)has been used in the treatment of primary biliary sclerosis.It is a relatively safe drug with a limited side effect profile(Paumgartner and Beuers, 2002). UDCA and related compound tauroursodeoxycholic acid have also been tested in cell and animal AD models (Viana et al., 2009; N?nes et al., 2012; Lo et al., 2013) and showed a putative protective effect (Ramalho et al., 2006; Viana et al., 2009; Lo et al.,2013; Dionísio et al., 2015). It has been shown that UDCA restores mitochondrial membrane potential in both sporadic AD and presenilin 1 (PSEN1) mutant fibroblasts via its actions on Drp1 while having no significant effect on mitochondrial morphology paving way for potential neuroprotective therapy for AD (Bell et al., 2018).

Ketogenic diet to shift heteroplasmy

Ketogenic treatment (i.e., low glucose, high ketone bodies)was shown to shift heteroplasmy in cybrid cell lines carrying deleted mtDNA. Although the mechanism of this shift is unclear, a selective stimulation of wild-type vs. mutant mtDNA replication has been proposed (Santra et al., 2004). While the neuroprotective mechanism has not been fully elucidated,several studies show that it increases the number and performance of mitochondria in neurons (Rho and Rogawski,2007; Hughes et al., 2014). J147 is an experimental drug with reported effects against both AD and aging in mouse models of accelerated aging (Chen et al., 2011; Prior et al., 2013)and is in Phase 1 clinical trial as of January 2019. Enhanced neurogenic activity over J147 in human neural precursor cells has its derivative called CAD-31. CAD-31 enhances the use of free fatty acids for energy production by shifting of the metabolic profile of fatty acids toward the production of ketone bodies, a potent source of energy in the brain when glucose levels are low (Daugherty et al., 2017). The target molecule is a protein called ATP synthase, which is found in the mitochondria.

Endurance exercise to enhance mitochondria function

Endurance exercise is neuroprotective against NDDs. Exercise activates continuous oxidative stress that induces a series of counteractive mechanisms that enhance mitochondrial function and mitigate ROS-induced neurotoxicity, i.e.mitohormesis (Onyango et al., 2010; Radak et al., 2016),and this is especially important in the hippocampus, which is particularly sensitive to oxidative stress (Intlekofer and Cotman, 2013). In animal models of AD, physical exercise reduces the noxious effects of oxidative stress, the production of total cholesterol, and insulin resistance, while increasing vascularization and angiogenesis, improving glucose metabolism as well as neurotrophic functions, thereby facilitating neurogenesis and synaptogenesis, and as a consequence improving memory and cognitive functions (Koo et al., 2015; Paillard et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016).

Targeting the inflammasome

The small molecule inhibitors of the NLRP3 inflammasome ameliorate AD pathology in animal models of AD (Dempsey et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2018). Further, CAD-31, a safe, orally active and brain-penetrant neurotrophic drug that targets inflammation has been shown to reduce synaptic loss,normalize cognitive skills and enhance brain bioenergetics in genetic mouse models of AD (Daugherty et al., 2017).

Cellular therapy

Cell-based therapies are a promising alternative currently being developed to enable the reversal of neurodegeneration either directly by replacing injured neurons or indirectly by stimulating neuronal repair via paracrine signaling at the injury site (Baraniak and McDevitt, 2010). Neurons and glial cells have successfully been generated from embryonic stem cells, neural stem cells, neural progenitor cells, mesenchymal stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, induced neuronal cells, and induced neuronal progenitor cells. Mesenchymal stem cells which are non-hematopoietic stem cells capable of differentiating into a multitude of cell lineages (Maijenburg et al., 2012), are the most commonly used cells in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine because they can promote host tissue repair through several different mechanisms including donor cell engraftment, release of cell signaling factors, and the transfer of healthy organelles to the host. Their transplantation into animal models of NDD have resulted in enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis, reversal of cognitive defects, clinical improvement and life extension of these animals (Kim et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015; Mendivil-Perez et al., 2017). It has been shown that human embryonic dopamine-neuron transplants survive in patients with severe PD and result in some clinical benefit in younger but not in older patients (Freed et al., 2001). While still in its formative phase, this new field shows great therapeutic promise for NDDs (Newell et al., 2018).

Intercellular mitochondrial transplantation

A novel approach for combating mitochondrial dysfunction is to supplement freshly isolated mitochondria (mitochondrial transplantation) to injury sites. This new paradigm of therapy delivers a supplement of healthy mitochondria into cells containing damaged mitochondria to enhance bioenergetics,reverse ROS production and restore mitochondrial function.A mechanism by which stroke induced activated astrocytes release mitochondria containing particles into damaged neurons through actin-dependent endocytosis to prevent neuronal death was recently discovered (Babenko et al., 2015;Hayakawa et al., 2016).

In stroke cases, astrocytes have been activated to release mitochondria-containing particles for intercellular transfer of mitochondria (to neurons) and it has been shown that supplement of freshly isolated mitochondria promotes neurite re-growth and restored the membrane potential of injured hippocampal neurons (Chien et al., 2018).In vivoPD models utilized a novel strategy of peptide-mediated allogeneic mitochondrial delivery (PMD) to improve functional incorporation of supplemented mitochondria into neurotoxininduced PD rats. Direct microinjection of Pep-1-modified allogeneic mitochondria into medial forebrain bundle promoted cellular uptake of mitochondria compared to the injection of na?ve mitochondria or xenogeneic PMD. The PMD successfully rescued impaired mitochondrial respiration,attenuated oxidative damage, sustained neuron survival, and restored locomotor activity of PD rats (Chang et al., 2016).The successful uptake of mitochondria by target tissues will depend upon the amount, quality of mitochondria and route of organelle delivery.

Using xenopeptides to bypass respiratory complexes defects

Single-peptide enzymes derived from yeast or low eukaryotes(xenopeptides) have been shown to bypass the block of the respiratory complexes (RC) due to defects in specific complexes in cellular and Drosophila models. The rationale for using these non-proton-pumping enzymes is that they reestablish the electron flow, thus reducing the accumulation of reduced intermediates and ROS production, while increasing ATP production by allowing proton pumping at the nonaffected complexes. The NADH reductase (Ndi1), which in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae transfers electrons from NADH to coenzyme Q, has been used to bypass complex I defects(Perales-Clemente et al., 2008; Sanz et al., 2010). Alternate oxidases, which in various organisms transfers electrons from coenzyme Q to molecular oxygen, have similarly been used to bypass complex III and complex IV defects. It is possible to safely use alternate oxidases to bypass OxPHOS defectsin vivoin mammalian systems without affecting major physiological parameters (El-Khoury et al., 2013; Dhandapani et al., 2019 ).

Alternate energy sources

In NDDs the activity of several mitochondrial enzymes is reduced (Golpich et al., 2017). Acetyl-CoA is necessary for the TCA cycle and the production of NADH and FADH2,which donate electrons to the ETC. Introduction of alternate energy sources (“biofuels”) could potentially alleviate mitochondrial dysfunction in AD. Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALC)being an endogenous component of the inner mitochondrial membrane capable of readily crossing the blood-brain barrier and providing acetyl groups to facilitate the synthesis of acetyl-CoA would bypass the need for PDH (Pettegrew et al., 2000). Additionally, ALC increases the production of glutathione, giving it a bipartite effect and further increasing its therapeutic appeal (Pettegrew et al., 2000). ALC is shown to have beneficial effects for a number of NDDs, including AD(Pettegrew et al., 2000). Chronic ALC administration reduces neuronal degeneration after spinal cord injury (SCI) in rats(Karalija et al., 2012) and maintains mitochondrial function,improves functional recovery while protecting both white and gray matter within the spinal cord from further injury(Patel et al., 2010, 2012). ALC administration also reduces the number of damaged mitochondria, improves mitochondrial membrane potential, and decreases SCI-induced apoptosis in rats (Zhang et al., 2015).

Photobiomodulation

Transcranial photobiomodulation/low level laser therapy) uses red/near infra-red light to stimulate, preserve and regenerate cells and tissues. Light stimulation of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase and ion channels in neurons leads to the activation of signaling pathways, up-regulation of transcription factors, and increased expression of protective genes and has been shown to provides neuroprotection in animal models of various NDDs (Hennessy and Hamblin,2017; Salehpour et al., 2018). “Remote photobiomodulation”,which involves targeting light at peripheral tissues, provides protection of the brain in an MPTP mouse model of PD,indicating that this may be a viable alternative strategy for overcoming penetration issues associated with transcranial photobiomodulation in humans where the scalp and skull may limit the utility of transcranial PBM in clinical contexts(Ganeshan et al., 2019).

Conclusion

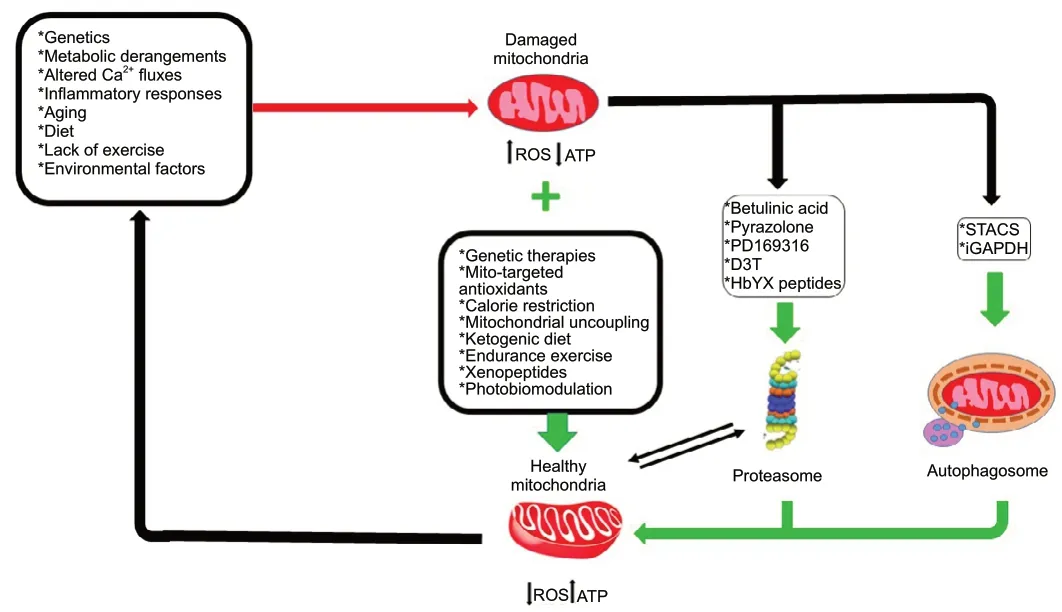

NDDs comprise complex, mostly sporadic age-dependent diseases that are becoming increasingly prevalent, partly because the global population and average lifespan continue to increase. With only symptomatic treatments currently available, they represent a major threat to human health and are of great concern socioeconomically. Mitochondrial dysfunction is central in these diseases as impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics and dynamics likely are major etiological factors in their pathogeneses of and have many potential origins. Addressing these multiple mitochondrial deficiencies is a major challenge of mitochondrial systems biology. We have reviewed evidence for mitochondrial impairments ranging from mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)mutations, to oxidative stress, altered gene expression,impaired mitobiogenesis, altered protein turnover and changed organelle dynamics (fission and fusion) and discussed potential approaches targeting each level of deficiency that might lead to the development of more effective, evidence based therapy (Figure 2).

Figure 2|Schematic illustration of mitochondrial impairments observed in neurodegenerative diseases and potential therapeutic approaches for each level of deficiency.

Author contributions:All authors contributed towards concept, design,literature search, and critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial support:This work was supported by the European Regional

Development Fund - Project MAGNET (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15_003/00 00492).

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its related enzymes and receptors play important roles after hypoxic-ischemic brain damage

- Environmental enrichment combined with fasudiltreatment inhibits neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 region and ameliorates memory deficits

- The secretome of endothelial progenitor cells:a potential therapeutic strategy for ischemic stroke

- The neuroimaging of neurodegenerative and vascular disease in the secondary prevention of cognitive decline

- Induced pluripotent stem cell technology for spinal cord injury: a promising alternative therapy

- The interaction of stem cells and vascularity in peripheral nerve regeneration