The interaction of stem cells and vascularity in peripheral nerve regeneration

Sara Saffari, Tiam M. Saffari, Dietmar J. O. Ulrich, Steven E. R. Hovius,Alexander Y. Shin

Abstract The degree of nerve regeneration after peripheral nerve injury can be altered by the microenvironment at the site of injury. Stem cells and vascularity are postulated to be a part of a complex pathway that enhances peripheral nerve regeneration; however,their interaction remains unexplored. This review aims to summarize current knowledge on this interaction, including various mechanisms through which trophic factors are promoted by stem cells and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis after nerve injury is stimulated by hypoxia, mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor, resulting in the growth of preexisting vessels into new areas. Modulation of distinct signaling pathways in stem cells can promote angiogenesis by the secretion of various angiogenic factors. Simultaneously,the importance of stem cells in peripheral nerve regeneration relies on their ability to promote myelin formation and their capacity to be influenced by the microenvironment to differentiate into Schwann-like cells. Stem cells can be acquired through various sources that correlate to their differentiation potential, including embryonic stem cells, neural stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells. Each source of stem cells serves its particular differentiation potential and properties associated with the promotion of revascularization and nerve regeneration. Exosomes are a subtype of extracellular vesicles released from cell types and play an important role in cell-to-cell communication. Exosomes hold promise for future transplantation applications, as these vesicles contain fewer membrane-bound proteins, resulting in lower immunogenicity. This review presents pre-clinical and clinical studies that focus on selecting the ideal type of stem cell and optimizing stem cell delivery methods for potential translation to clinical practice. Future studies integrating stem cell-based therapies with the promotion of angiogenesis may elucidate the synergistic pathways and ultimately enhance nerve regeneration.

Key Words: angiogenesis; exosomes; nerve graft; nerve regeneration; peripheral nerve injury; revascularization; Schwann cells; stem cells; stem cell delivery; vascularity

Introduction

Patients with peripheral nerve injuries (PNI) can face severe disability resulting in sensory loss, motor deficits, and neuropathic pain. These deficits may result in a devastating impact on a patient’s quality of life (Sullivan et al., 2016).Despite advancements in microsurgical techniques and basic and translational research, surgical reconstruction of PNIs continues to have unsatisfactory clinical outcomes, particularly for reconstructions of major mixed motor and sensory nerves(Lundborg, 2000; Khalifian et al., 2015). When end-to-end tension-free neurorrhaphy is not possible, the current gold standard remains reconstruction with autologous cabled nerve graft interposition after excision of the injured nerve stumps.Harvest of autologous nerves faces associated drawbacks,such as permanent donor site morbidity with loss of sensation in the distribution of the harvested nerve (Sunderland, 1952;Terzis et al., 1975; Ray and Mackinnon, 2010; De la Rosa et al.,2018). Attempts to create a commercially available nerve graft substitute have resulted in a variety of bioabsorbable synthetic conduits or decellularized human allograft nerves. Their clinical efficacy has yet to equal or surpass autologous nerve grafts, especially for defects greater than three centimeters(Kornfeld et al., 2019).

Engineering of a synthetic substrate for nerve regeneration to mimic the ultrastructure of autologous nerves has been extremely challenging. The use of human allograft fresh nerves for reconstruction requires systemic immunosuppression to prevent graft rejection and is associated with side effects,such as severe opportunistic infections (Bulatova et al., 2011;Saffari et al., 2019). An alternative to fresh human allograft nerves or to engineering a nerve graft is to decellularize and process human allograft nerve. Decellularized allografts serve as a temporary scaffold for regenerating nerve fibers and do not require systemic immunosuppression due to diminished graft rejection potential. Decellularized allografts provide the essential ultrastructural elements and may be pretreated with irradiation, cold preservation, trophic factors, or seeded with Schwann cells or stem cells, to advance outcomes after peripheral nerve reconstruction (De la Rosa et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2018). Stem cell-based therapy may offer a suitable treatment with several regenerative benefits to restore neuronal function, including supporting remyelination and revascularization of the affected organ (Jiang et al., 2017).Specifically, stem cells that have been differentiated into Schwann-like cells, mimicking the function of the original facilitators of axonal regeneration, may enhance neuron survival to improve functional outcomes (Keilhoff et al., 2006;De la Rosa et al., 2018). Growth factors secreted by stem cells may enhance angiogenesis, the sprouting of new capillaries from preexisting ones, to promote revascularization (Risau,1997; Rissanen et al., 2004; Caplan, 2015; Mathot et al.,2019).

The exact interaction between stem cells and vascularity remains unexplored and is postulated to be part of a complex pathway that enhances peripheral nerve regeneration. This review will provide an in-depth perspective of currently available stem cell-based therapy applications in PNIs and discusses the interaction between stem cells and vascularity in peripheral nerve regeneration. Furthermore, sources of stem cells, methods of delivery to the injury site, relevant preclinical studies and clinical trials, and future applications will be reviewed.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

Literature research was performed using PubMed, Web of Science, MEDLINE and Google Scholar databases, using the following search terms: angiogenesis, vascularity, nerve regeneration, nerve transplantation, nerve graft, neural stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells, exosomes and various combinations of the above terms. Available English studies discussing stem cells and vascularity in peripheral nerve injuries in both animals and humans were included until July 2020.

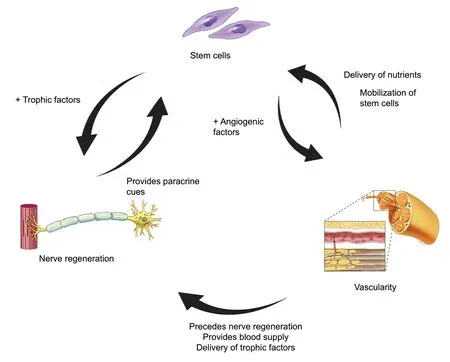

Interaction of Stem Cells, Vascularity and Nerve Regeneration

The interaction of stem cells, vascularity, and axon regeneration is complex (Figure 1). The paracrine property of stem cells is much broader than previously was appreciated.When stimulated by surrounding tissues, stem cells have the ability to affect vascularity via cell-to-cell communication,differentiation, and release of angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Rehman et al.,2004; Hong et al., 2010; Watt et al., 2013). On the other hand, stem cells demonstrate the capacity to stimulate the upregulation of neurotrophic factors to enhance nerve regeneration as a response to nerve injury (Kondo et al., 2009;Hong et al., 2010; Rbia et al., 2018; Mathot et al., 2019).After nerve injury, angiogenesis is stimulated by hypoxia,usually mediated by VEGF, resulting in the growth of preexisting vessels into new areas. It is postulated that these newly modeled vessel tracks precede the repair of damaged nerves (Carmeliet et al., 1996; Risau, 1997; Rissanen et al.,2004; Saffari et al., 2020a). The therapeutic potency of stem cells in nerve regeneration and vascularity is influenced by its microenvironment. The interaction of the environment,stem cells, and vascularity with respect to peripheral nerve regeneration will be discussed per causal order below.

Figure 1|Schematic drawing of interaction between stem cells,vascularity, and nerve regeneration.

Stem cells and revascularization of nerve

Blood vessels have been postulated to be a systemic source of stem cells in regenerating hematopoietic cells secondary to their vascular origin. Embryologically, hematopoietic stem cells emerge closely in the vicinity of vascular endothelial cells(Tavian et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2012). The subendothelial zone, located in the tunica intima of blood vessels, has been specifically implicated as a source of endothelial progenitor cells (Zengin et al., 2006). Evidence has demonstrated that other structural layers also serve as niches for stem cells that are mostly quiescent and are activated in response to injury (Zhang et al., 2018). The close vicinity of these progenitor cells to the circulation allows for their mobilization to the region of interest to facilitate a number of processes including tissue regeneration (Fakoya, 2017). Differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into Schwann-like cells enhances the secretion of various angiogenic factors, including angiopoietin-1 and VEGF-A, resulting in enhanced angiogenic potency and neurite outgrowth (Kingham et al., 2014; Mathot et al., 2019). MSCs differentiated into Schwann-like cells specifically, have been shown to increase revascularization of nerve allografts afterin vivoreconstruction of sciatic nerve defects in rats (Mathot et al., 2020a).

Revascularization of nerve and neural regeneration

Following PNI, axons and myelin degenerate distally to the injury site by interactions of Schwann cells and macrophages in a process known as Wallerian degeneration (Waller, 1851;Cheng et al., 2017). During regeneration, blood vessels precede axonal extension and serve as tracks for Schwann cells to migrate and guide axonal growth, suggesting interdependence between neurite outgrowth and vascularity(Hobson et al., 1997; Hobson, Green et al. 2000). VEGF is central to the control of angiogenesis and critical in the process of maturation and stabilization of vessels (Connolly et al., 1989; Akhavani et al., 2008). In addition to stimulating the outgrowth of Schwann cells and blood vessels, VEGF also enhances axonal outgrowth from dorsal root ganglia (Sondell et al., 1999). It has been proposed that VEGF improves hematopoietic stem cell survival by an internal autocrine loop mechanism (Sondell et al., 1999; Gerber et al., 2002). This mechanism implies that it is not accessible for extracellular inhibitors, such as antibodies, to block this loop and proposes that the VEGF-dependent loop is solely generated in stem cells and not in endothelial cells (Gerber et al., 2002).

VEGF had become the focus of numerous basic science studies and was used to augment nerve grafts. However, it was found that the angiogenic effect of VEGF did not translate into enhanced motor recovery (Lee et al., 2016), suggesting that the role of vascularity in nerve regeneration does not depend on one element solely, but is broader and more complex(Saffari et al., 2020a). Recent research investigated the effect of an adipofascial vascularized flap on nerve revascularization in nerve allografts using novel microcomputed imaging.These results suggest that revascularization patterns follow longitudinal inosculation, the growth of host vessels from nerve coaptation ends, occurring primarily from proximal,rather than from both nerve ends, as previously believed(Chalfoun et al., 2003; Saffari et al., 2020b). Organized longitudinally running vessels provide modeled vessel tracks to precede the repair of damaged nerves (Carmeliet et al.,1996; Risau, 1997; Rissanen et al., 2004; Saffari et al., 2020a).

Stem cells and nerve regeneration

The importance of stem cells in peripheral nerve regeneration relies on their ability to enhance neurotrophic factors,promote myelin formation, and their capacity to be influenced by the microenvironment to differentiate into Schwann-like cells (Jiang et al., 2017). Schwann cells are essential within the context of peripheral nerve regeneration after trauma and are crucial during Wallerian degeneration, however,difficult to transplant (Salzer and Bunge, 1980; De la Rosa et al., 2018). The acquisition of autologous Schwann cells requires the harvest of large segments of healthy nerve tissue,resulting in donor site morbidities. Additionally, proliferation of Schwann cellsin vitrois associated with an extensive culturing and expansion time period. As a result of these limitations, research has been directed towards the use of MSCs, which are easily accessible, and can be differentiated into Schwann-like cells (De la Rosa et al., 2018). Schwannlike cells are found to express neurotrophic factors and to interact through multiple pathways to support the repair of injured nerves (Tomita et al., 2013; Mathot et al., 2019).These factors and pathways include nerve growth factor(NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and myelin related growth factors. BDNF is upregulated in motor neurons and increases myelin thickness in regenerating nerves while promoting remyelination and axonal sprouting (Gordon, 2009;De la Rosa et al., 2018). In myelin sheath formation, a number of myelin proteins are induced such as myelin basic protein,peripheral myelin protein-22, and pleiotrophin. Pleiotrophin is involved in myelinated axon regeneration specifically and is increasingly expressed in differentiated MSCs in comparison to undifferentiated MSCs (Mi et al., 2007; Mathot et al.,2020b). The level of growth factors in the microenvironment influences the sequential growth factor production by the transplanted stem cells, emphasizing their paracrine feedback properties.

Only 5% of all types of stem cells can spontaneously differentiate into Schwann cells; however, pre-differentiation towards the desired phenotypein vitrovia chemical induction or transfection with growth factors has been shown to be a more effective method to increase the number of Schwannlike cells (Cuevas et al., 2002; Dore et al., 2009; Jiang et al.,2017). Drawbacks of pre-differentiation include the need for additional preparation time and higher costs, making this process less favorable for clinical translation (Mathot et al., 2019). More investigation is needed to confirm the optimal dosage of transplanted stem cells, delivery methods,in vivosurvivability, and interaction mechanisms with their environment prior to conducting clinical studies.

Stem Cell Sources

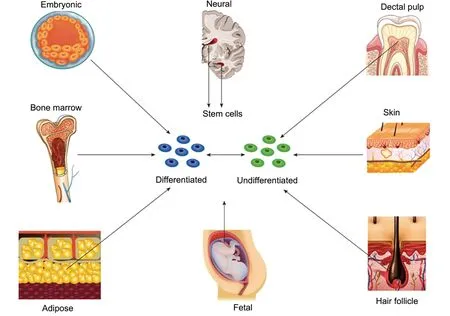

Stem cells can be categorized as embryonic stem cells or adult stem cells according to their development stage, which relates to their differentiation potential. An overview of all stem cell sources is provided inAdditional Table 1.

Embryonic stem cells

Thomson et al. (1998) described the isolation of pluripotent cell lines from the inner cell mass of human blastocyst-stage embryos. Following this discovery, stem cells have been harvested from several fetal as well as adult tissues (Figure 2). Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are undifferentiated cells,capable of self-renewal and have superior differentiation potential and long-term proliferation capacity compared to adult stem cells. ESCs have the ability ofin vivomyelination since they can differentiate into neurons and glial cells of the central and peripheral nervous system. In humans, the use of ESCs in neural tissue engineering is primarily inhibited by the ethical controversy of the use and destruction of a human embryo. Additional limitations include ESC’s immunogenicity and carcinogenic potential including teratoma formation which limits clinical translation. Differentiation of ESCs into specialized neural cell lines remains challenging and protocols have only been established for a few cell lines (Cui et al., 2008;Fairbairn et al., 2015; De la Rosa et al., 2018; Jones et al.,2018; Yi et al., 2020).

Figure 2|Schematic overview of different sources of stem cells.

Neural stem cells

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are naturally capable of differentiating into neurons or glial cells and play a role during neurogenesis in the development of the brain and spinal cord, which almost exclusively occurs during embryogenesis.In human adults, NSCs are located in the subventricular zone and hippocampus and have a limited role in the regeneration of central nervous system injuries (Paspala et al., 2011;Fairbairn et al., 2015; Matarredona and Pastor, 2019). While several basic science studies suggest enhancement of nerve regeneration following NSC administration to the injury site after both acute and chronic PNI (Heine et al., 2004; Fairbairn et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017), commercially available NSCs have been reported to be associated with the formation of neuroblastoma after implantation (Johnson et al., 2008).Additional limitations to application in humans include the technical difficulties associated with cell harvest and the need to direct differentiation of specialized neural cell lines. The application of NSCs could greatly benefit clinical practice if these limitations can be overcome (Wang et al., 2017).

Mesenchymal stem cells

The multipotent MSCs can be derived from the bone marrow and a wide range of non-marrow sources, including adipose tissue, peripheral blood, amniotic fluid, umbilical cord, tendon and ligaments, hair follicle, synovial membranes, olfactory mucosa, dental pulp and fetal tissue (Maltman et al., 2011).Their potentials for differentiation, ease of isolation, and immunomodulation have contributed to their considerable application in tissue regeneration. MSCs have the ability to differentiate into all mesoderm lineages: adipose tissue,bone, muscle, and cartilage (Pittenger et al., 1999) and serve as targets for genetic modification. Depending on the appropriate stimuli and environmental conditions, MSCs have shown to express plasticity and transdifferentiation and can be differentiated into non-mesenchymal lineages, such as neurons, astrocytes, Schwann-cell like cells and myelinating cells of the peripheral nervous system to enhance nerve regeneration (Tohill et al., 2004; Fairbairn et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2017; De la Rosa et al., 2018). Bone marrow-derived and adipose-derived MSCs are the most commonly used stem cells for PNI.

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs)can differentiate into non-mesodermal lineages such as neurons, astrocytes, and Schwann-like cells under appropriate environmental conditions (Tohill et al., 2004).Consequently, BMSCs may enhance neurite outgrowth and express neurotrophic factors (NGF, BDNF, glial cell linederived neurotrophic factor, and ciliary neurotrophic factor)as well as extracellular matrix components including collagen,fibronectin, and laminin. Administration of BMSCs to nerves contributes to enhanced angiogenesis (Chen et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2012; Fan et al., 2014; Yi et al., 2020).A number of studies in rodent models have found that BMSC application to conduits and acellular nerve grafts resulted in superior functional outcomes in nerve regeneration compared to untreated grafts (Cui et al., 2008; Fairbairn et al., 2015).BMSCs demonstrated dose-dependent enhancement of the extent of myelination, thickness of myelin sheath, and axonal thickness in a rat sciatic nerve model (Raheja et al., 2012).When cultured, BMSCs lack immune recognition and have immunosuppressive action, which may overcome induced immune rejection after allogenic transplantation (Aggarwal and Pittenger, 2005; Yi et al., 2020). Although BMSCs are more easily harvested than ESCs and NSCs and have minimal ethical use issues, BMSCs have inferior proliferation capacity and differentiation potential. The harvesting procedure is invasive and painful for donors and the quantity of stem cells obtained is lower compared to other sources (Fairbairn et al., 2015;Jiang et al., 2017).

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) can easily be harvested from abundant adipose tissue with minimally invasive procedures such as liposuction. Compared to BMSCs, ADSCs show superior stem cell fraction, proliferation,and differentiation potential. ADSCs can be differentiated into a Schwann cell-like phenotype, sharing functional and morphological characteristics, and similar effectivity levels as autologous Schwann cells. It is postulated that ADSCs facilitate endogenous Schwann cell recruitment by expressing growth factors such as NGF, VEGF, and BDNF leading to a longlasting therapeutic effect promoting nerve regeneration and protection, which outlasts the life span of ADSC (Kingham et al., 2007; Erba et al., 2010; Fairbairn et al., 2015).Interestingly, ADSCs are reported to support angiogenesis by direct differentiation into vascular endothelium, as well as by associated paracrine effects (Chen et al., 2011; Nie et al., 2011). Difficulties include the unfavorable differentiation potential towards adipocytes (Faroni et al., 2016).Nonetheless, ADSCs are currently the most practical source of stem cells to obtain and have been and continue to be translated to clinical use (Fairbairn et al., 2015).

Other types of MSCs including fetal derived stem cells, skinderived precursors, muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells,hair follicle stem cells and dental pulp stem cells, as well as induced pluripotential stem cells are detailed inAdditional Table 1(Fairbairn et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2017). Currently,inherent disadvantages associated with MSC-based therapy still exist: instability of the cellular phenotype, high cost,ethical issues, and difficulties of cellular origin (Dong et al.,2019). These difficulties may be overcome by the application of exosomes.

Exosomes

Recent research has proven that the therapeutic effect of MSCs is highly likely to be accredited to the indirect regeneration of endogenous Schwann cells through cellular paracrine mechanisms, which are partially thought to be mediated by MSC exosomes (Sowa et al., 2016). MSC exosomes are a subtype of extracellular vesicles released from all cell types,but particularly from stem cells. MSC exosomes are located in nearly all biological body fluids including blood, urine, breast milk, ascites, and saliva (Kourembanas, 2015). These particles maintain cell-to-cell communication by delivering proteins,lipids, DNA, mRNA, and micro ribonucleic acids miRNAs(miRNA), and other subtypes of RNA, which regulate cell biological behavior and can be used to mediate intercellular communication (Corrado et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017; Blanc and Vidal, 2018; Rezaie et al., 2018). MSC exosomes are found to increase axonal regeneration and promote local angiogenesis by transmitting a number of genetic materials,neurotrophic factors and proteins to axons and thereby restoring the homeostasis of the microenvironment (Dong et al., 2019). Furthermore, MSC exosomes have been proven to promote the proliferation of Schwann cells and reduce their apoptosis rate by upregulating the pro-apoptotic Bax mRNA expression resulting in increased regeneration (Liu et al., 2020). It is postulated that MSC exosomes are mediators of communication with vascular endothelial cells resulting in enhancement of the plasticity of blood vessels following PNI(Gong et al., 2017). MSC exosome-based therapy provides many benefits including the decrease of associated risks with transplantation as exosomes contain fewer membrane-bound proteins. These characteristics present MSC exosomes with lower immunogenicity, the ability to cross biological barriers,and to be more stable over time (Qing et al., 2018; Dong et al., 2019). The primary limitation of exosomes application is the limited scientific support and lack of standardized techniques for its isolation, quantification and purification.The efficacy of injected MSC exosomes and the effect of MSC exosomes travelling through the body remains unknown and to be explored (Qi et al., 2020).

Additionally, no guidelines for ethical safety assessment exists yet. MSC exosomes have great potential to be utilized for future therapeutic strategies in clinical practice following PNI if these challenges can be addressed (Dong et al., 2019).

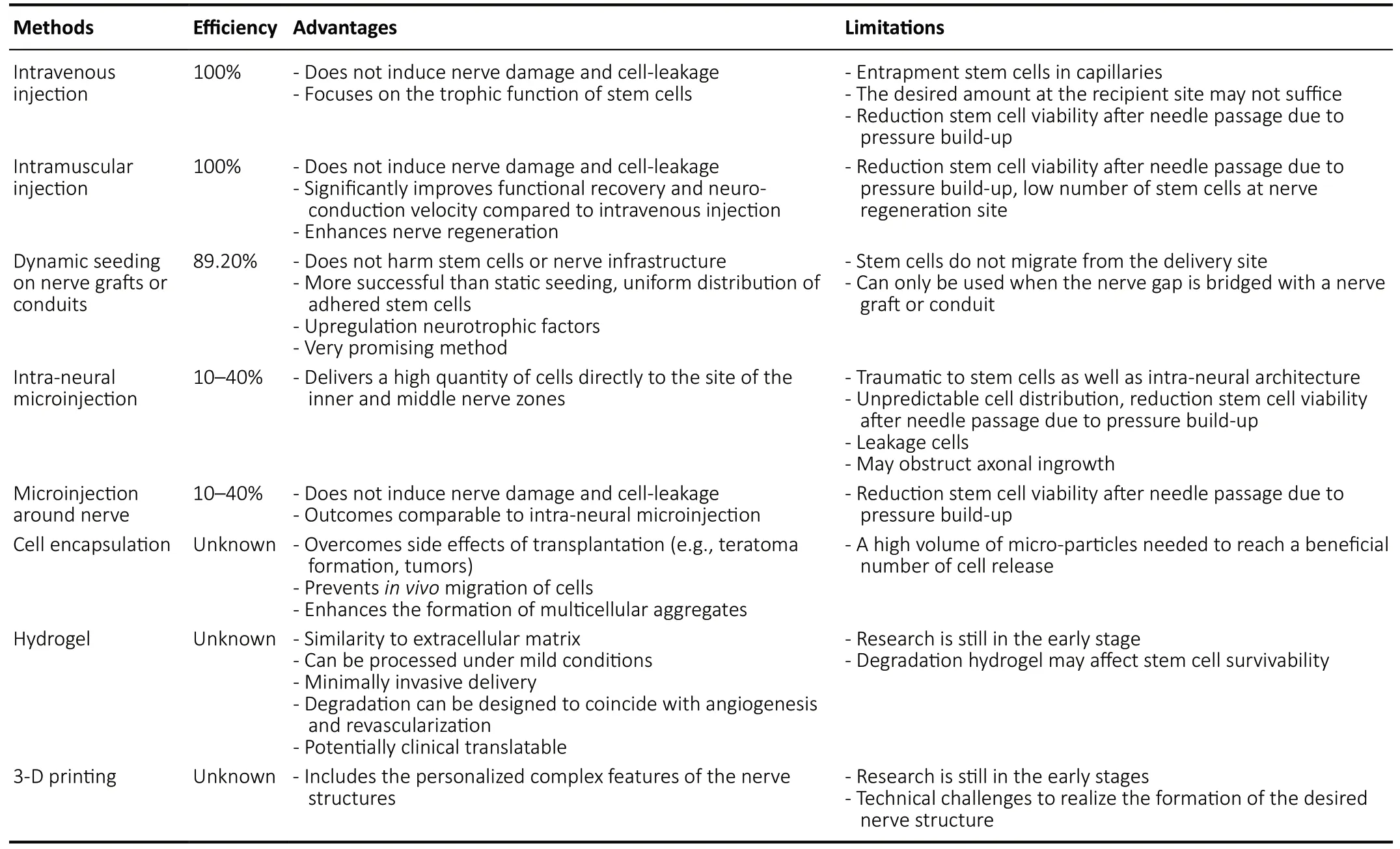

Mode of Stem Cell Delivery

Stem cells can be delivered to the nerve reconstruction site by a variety of methods (Table 1). The selection of the delivery method depends on the intended mechanism of action of the stem cells. The process of microinjection (either intraneural, around the nerve, intramuscular or intravenous)decreases the viability of stem cells due to the traumatic damage secondary to the pressure build-up in the syringe and flow through the needle during injection. Furthermore,intra-neural microinjection of stem cells is associated with damage of the nerve ultrastructure with unpredictable cell distributions, obstruction of axonal ingrowth, and leakage of cells (Lévesque et al., 2009; Fairbairn et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2017; Mathot et al., 2019). Dynamic seeding has been a successful technique in delivering stem cells and results in an efficient and uniform distribution of stem cells. When cells are dynamically seeded on the surface of a decellularized nerve allograft, these cells remain viable on the nerve surface allowing for interaction with the nerve ultrastructure and resulting in the upregulation of neurotrophic factors (Rbia et al., 2018; Mathot et al., 2019).According to Mathot et al. (2019), an efficiency of at least 1 × 106MSCs on a 10-mm nerve graft is needed to generate noticeable outcomes. Induced differentiation of MSCs may have an effect on the final efficiency, as delivery methods have only been tested on undifferentiated MSCs, however, its effect remains unknown. Controversy remains on the optimal method of delivery and requires further evaluation.

Table 1 |Overview of delivery methods of stem cells, showing its efficiency, advantages, and disadvantages

The Regenerative Potential of Cell-Based Therapy

The regenerative potential of cell-based therapy following nerve injury is particularly relevant for large diameter and long nerve defects (Faroni et al., 2015). In rodent models,extensive research using stem cells in peripheral nerve repair suggests that the application of stem cells enhances functional motor outcomes. It has been shown that stem cells elevate expression of neurotrophic factors, angiogenic growth factors and contribute to angiogenesis (Zhao et al.,2011; Fan et al., 2014; Mathot et al., 2020b; Yi et al., 2020).The exact survivability of stem cellsin vivo, however, is difficult to investigate and remains largely unknown. When MSCs were dynamically seeded on nerve allografts,in vivosurvivability up to 29 days was found using luciferase-based bioluminescence imaging (Rbia et al., 2019). This suggests that survivability of stem cells may be hampered by rejection,inflammation, or migration. Larger animal models are also investigating augmentation of nerve repair outcomes by the provision of BMSCs to nerve grafts (Ding et al., 2010;Muheremu et al., 2017). Tissue-engineered nerve grafts enhanced with autologous BMSCs have been used to repair 50 mm-long median nerve defects in rhesus monkeys. After 1 year, histological and morphometric analyses of regenerative nerves found results comparable to autograft repair. Blood samples and histopathological examination of nerve found no immune rejection, confirming that tissue-engineered nerve grafts augmented with BMSCs were safe to use in monkeys (Hu et al., 2013). Extensive investigations of safety in preceding pre-clinical trials have provided the data necessary to proceeding evaluation of MSCs in clinical trials (Pal et al.,2009).

Clinical stem cell application is novel and has been applied to several fields including treatment for cardiovascular diseases with promising results (Hong et al., 2010). Several clinical trials investigating central nervous system diseases, including spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury, have proven the safety of MSC application. Ongoing trials suggest that MSCs prepare the environment of injury for axonal ingrowth and stimulate angiogenesis. While this is promising, more studies are needed to assess the time and route of administration to obtain more consistent data (Badyra et al., 2020). In the field of PNI, most clinical trials related to stem cell treatment focus on hemifacial spasm, burn wound healing and diabetic peripheral neuropathy (De la Rosa et al., 2018) and are still in the early phases. Although the application of Schwann cells is not desired due to the aforementioned limitations, the first FDA-regulated dose phase I trial on human Schwann cell transplantation in spinal cord injuries has found promising results with no adverse effects (Anderson et al., 2017).Currently, little pre-clinical or clinical research has addressed the interaction of stem cells and vascularity in nerve regeneration, which creates an opportunity for elucidating its synergistic pathways in future research.

Future Applications

Future applications integrating stem cell-based therapies with the promotion of angiogenesis are needed to enhance nerve regeneration through multiple pathways. Feasibility with respect to cost and time efficiency is needed for translation to clinical practice. Current research developing future applications includes prevascularized stem cell nerve conduits,three-dimensional printing, and hydrogel scaffolding (Fakoya,2017; Du and Jia, 2019; Fan et al., 2020).

Fan et al. (2020) have developed a novel prevascularized nerve conduit based on a MSC sheet for treating spinal cord injuries, resulting in enhanced nerve regeneration and revascularization. Other novel research has focused on threedimensional printing in order to fabricate a nerve guidance conduit with stem cells that reproduces the complex nerve features of a patient’s long nerve defect, such as branching nerve networks and intrinsic chemical mechanisms that steer regenerating motor and sensory axons along correct anatomical pathways. Three-dimensional printing may provide the desired personalized dimensions and structures for nerve regeneration and cell organization (Du and Jia, 2019).

Another novel future application focuses on promising stem cell delivery methods, which are still in early stages of research, such as stem cell encapsulation delivered in a hydrogel scaffold (Fakoya, 2017; Allbright et al., 2018).Hydrogels constructed of natural biomaterials, including collagen and fibrin, as well as synthetic biomaterials such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) and polyethylene glycol, may act as carriers for delivery of stem cells or growth factors.The use of hydrogel as a scaffold is attractive due to its high water content mimicking an extracellular matrix as well as its ease of delivery. Hydrogel degradation can be designed to respond to tissue proteases and to deliver stem cells or other growth factors in a timely manner to coincide with the processes of angiogenesis. In vascular tissue engineering,poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) hydrogels have been designed to ensure a controlled release of angiogenic factors such as VEGF for an extended release time. Basic criteria for the use of hydrogel include effective cell adhesion to the gel matrix,sufficient stem cell survival in the hydrogel, safety for the micro-environment, and mechanical stability (Fakoya, 2017;Maiti and Díaz, 2018). The use of prefabricated conduits or encapsulated cells locally delivered in a hydrogel is feasible,has strong potential to enhance survival of transplanted cells and may be less immunogenic when combined with exosomes.

As tissues consist of multiple cell types, potential synergistic therapeutic benefit may occur when multiple stem cell types are administered simultaneously. By combining the properties and secretion of a mixture of neuroregenerative as well as vascular growth factors, cytokines and miRNA,regenerative capacities may be enhanced. Currently, limited data supporting combined cell type administration exist,however, may be promising for future applications (Williams et al., 2013; Avolio et al., 2015). The ideal type of stem cell for translation needs to be easily accessible and harvested,proliferate rapidly without carcinogenic consequences, and immune-compatible. Locally delivered cell-based therapy is expected to increasingly take part in enhancing outcomes after nerve reconstruction in the next decades.

Conclusions

Improved understanding of the interaction of stem cells and vascularity will provide therapeutic targets to improve outcomes after peripheral nerve reconstruction. The degree of nerve regeneration after PNI is particularly dependent on the local environment of injury and may be altered to promote functional recovery. The microenvironment may be modulated by stem cells and angiogenesis. This topic of interest is complex and involves the secretion of trophic factors that enhance regeneration and revascularization.Revascularization of nerve is suggested to enhance nerve regeneration by organized longitudinally running vessels that provide modeled vessel tracks to precede the repair of damaged nerves. The effect of stem cells, on the other hand,is dependent on their differentiation potential and stimulation by paracrine cues, which are provided by the environment during nerve regeneration. This review discusses the synergistic pathways of stem cells and vascularity and their interaction with nerve following PNI. Despite advancements in well-designed pre-clinical studies, translation of stem cells to clinical practice is currently impeded by ethical issues,risk of tumorigenesis, unknown side-effects and technical challenges. Future research may be shifted towards the use of exosomes, to overcome difficulties associated with the harvest and culture of stem cells. Local modulation of nerve environment is still evolving, and the importance of stem cell and vascularity-based therapies is expected to take a larger part in treatment options of PNIs.

Acknowledgments:We would like to thank Dr. Fairbairn and colleagues,and the World Journal of Stem Cells for granting us the permission to reprint Figure 2.

Author contributions:SS and TMS worte the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Financial support:None.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewer:Annas Al-Sharea, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Vic, Australia.

Additional files:

Additional Table 1:Overview of sources of stem cells, showing its origin,location of harvest, properties, and mechanisms.

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its related enzymes and receptors play important roles after hypoxic-ischemic brain damage

- Environmental enrichment combined with fasudiltreatment inhibits neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 region and ameliorates memory deficits

- Regulation of neuronal bioenergetics as a therapeutic strategy in neurodegenerative diseases

- The secretome of endothelial progenitor cells:a potential therapeutic strategy for ischemic stroke

- The neuroimaging of neurodegenerative and vascular disease in the secondary prevention of cognitive decline

- Induced pluripotent stem cell technology for spinal cord injury: a promising alternative therapy