The secretome of endothelial progenitor cells:a potential therapeutic strategy for ischemic stroke

Mansour Alwjwaj, Rais Reskiawan A. Kadir, Ulvi Bayraktutan

Abstract Ischemic stroke continues to be a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the world.Despite recent advances in the field of stroke medicine, thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator remains as the only pharmacological therapy for stroke patients. However, due to short therapeutic window (4.5 hours of stroke onset) and increased risk of hemorrhage beyond this point, each year globally less than 1% of stroke patients receive this therapy which necessitate the discovery of safe and efficacious therapeutics that can be used beyond the acute phase of stroke. Accumulating evidence indicates that endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), equipped with an inherent capacity to migrate, proliferate and differentiate, may be one such therapeutics. However, the limited availability of EPCs in peripheral blood and early senescence of few isolated cells in culture conditions adversely affect their application as effective therapeutics. Given that much of the EPC-mediated reparative effects on neurovasculature is realized by a wide range of biologically active substances released by these cells, it is possible that EPC-secretome may serve as an important therapeutic after an ischemic stroke. In light of this assumption,this review paper firstly discusses the main constituents of EPC-secretome that may exert the beneficial effects of EPCs on neurovasculature, and then reviews the currently scant literature that focuses on its therapeutic capacity.

Key Words: antioxidants; cell-based therapy; cell-free therapy; endothelial progenitor cells;inflammatory cytokines; regenerative medicine; secretome; stroke; vasodegeneration;vasorepair

Introduction

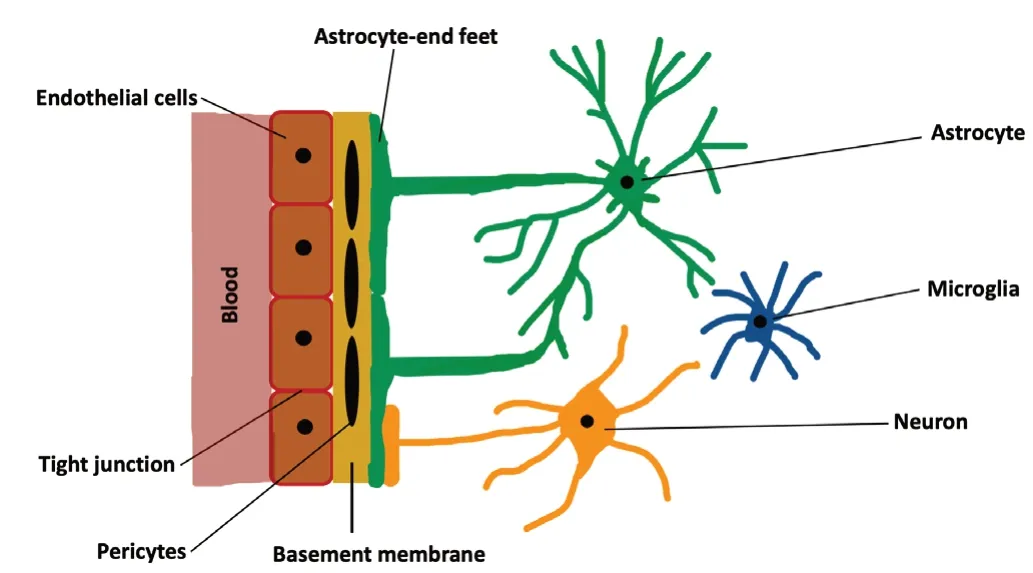

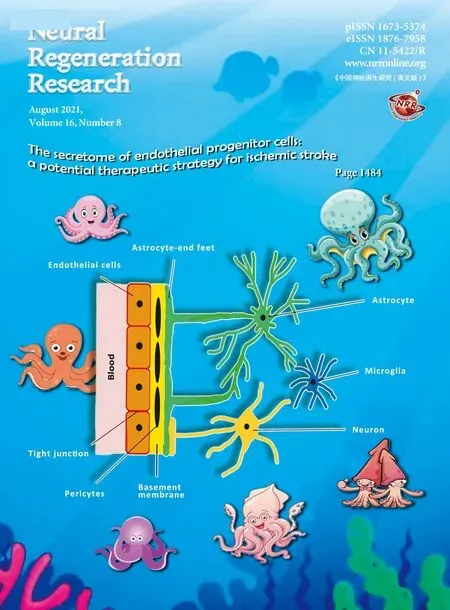

According to the World Health Organization, each year about 15 million people suffer a first stroke in the world.Sadly, while one-third of these patients die, another onethird live with long-term disabilities inflicted by this condition(Ma et al., 2015). Hence, stroke continues to be one of the major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide (Hisham and Bayraktutan, 2013; Liao et al., 2017). Ischemic strokes,stemming from an interruption of blood flow to the brain,make up about 80–85% of all strokes. Despite being the main cause of human cerebral damage, systemic thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator or endovascular treatment remain the only therapeutic options for this disease(Allen and Bayraktutan, 2009; Reis et al., 2017). However,due to short therapeutic window and stringent eligibility criteria, each year less than 1% of stroke patients worldwide receive either therapy (Hacke et al., 2008; Bayraktutan, 2019).This necessitates the discovery of novel therapeutic agents that can be safely and effectively used beyond the acute (or hyperacute) phase of ischemic stroke. Although over the years many agents targeting various mechanisms associated with ischemic stroke, such as excitotoxicity or oxidative stress, have generated favorable results in experimental settings, subsequent clinical trials have failed to replicate these favorable outcomes. As depicted inFigure 1, complexity of human neurovascular unit (NVU), a dynamic structure formed by direct contact, signaling and interactions amongst microglia, astrocytes, neurons and endothelial cells, has been proposed to explain this apparent dichotomy (Serlin et al.,2015). Blood-brain barrier (BBB) makes up a critical part of this unit and is composed of brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), capillary basement membrane (BM), pericytes embedded in the BM and astrocyte end-feet enclosing the blood vessels (Ballabh et al., 2004; Zehendner et al., 2009).Although its structural and functional integrity are critical in maintaining cerebrovascular homeostasis, the BBB is also an important obstacle for the delivery of so-called efficacious therapeutics. The BMECs cover the entire luminal part of all brain capillaries and constitute the main cellular component of the BBB. They differ from the endothelial cells of other organs in that they are joined together with tight junction proteins, lack fenestrae, have low number of intracellular mitochondria and possess specific transport systems that actively carry the nutrients from blood to the brain (Petty and Lo, 2002; Weiss et al., 2009). Tight junctions limit passive molecular diffusion through the BBB by forcing molecular traffic away from paracellular routes to transcellular routes(Wolburg and Lippoldt, 2002; Nag, 2003; Abbott et al., 2006).The BM surrounds the BMECs, accommodates pericytes,makes connections with astrocyte end-feet and appears to play a role in tight junction formation (Carvey et al., 2009).The pericytes enclose the blood vessel wall, make direct contact with the BMECs, facilitate angiogenesis and play a role in preserving microvascular stability (Zhao et al., 2015). The astrocyte end-feet enclose the outer side of the blood vessels,help maintain the integrity and function of the BBB and block the differentiation of pericytes from resting to a contractile stage (Yao et al., 2014).

Figure 1|Schematic representation of neurovascular unit.

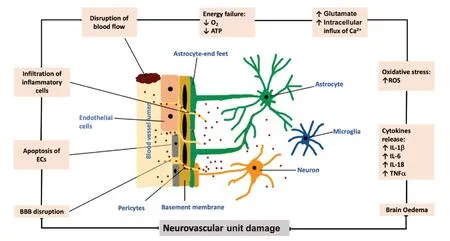

Sudden decreases in cerebral blood flow during an ischemic stroke may perturb NVU structural integrity and impair overall cerebral function through involvement of a series of mechanisms including depleted generation of adenosine triphosphate, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress and inflammation(Lipton and Rosenberg, 1994; del Zoppo and Hallenbeck,2000; Allan and Rothwell, 2001; Doyle et al., 2008; Williams-Karnesky and Stenzel-Poore, 2009; Deb et al., 2010; Martin and Wang, 2010; Woodruff et al., 2011; Xing et al., 2012;Fann et al., 2013; Brennan-Minnella et al., 2015; Prakash and Carmichael, 2015). As illustrated inFigure 2, excitotoxicity harms NVU through increases in sodium and calcium influx triggered by accumulation of extracellular excitatory amino acids, glutamate and aspartate (Lipton and Rosenberg,1994; Williams-Karnesky and Stenzel-Poore, 2009; Deb et al., 2010; Martin and Wang, 2010; Woodruff et al., 2011;Xing et al., 2012; Fann et al., 2013; Brennan-Minnella et al.,2015). Oxidative stress and post-ischemic inflammation,characterized by excessive availabilities of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin(IL)-1β, IL-18, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α harm NVU by disrupting structural integrity of the tight junctions (del Zoppo and Hallenbeck, 2000; Allan and Rothwell, 2001; Doyle et al.,2008; Fann et al., 2013; Prakash and Carmichael, 2015).

Figure 2|Schematic representation of the effect of ischemic stroke on neurovascular unit.

Search Strategy

For the present review, we searched the literature using keywords such as endothelial progenitor cells, outgrowth endothelial cells, blood outgrowth endothelial cells, circulating endothelial colony forming cells, EPCs, OECs, secretome,growth factors, chemokines, cytokines, adhesion molecules,proteases, shed receptors, release, secrete, secretion,ischemia, infarction, vascular injury, endothelial injuries,reperfusion injury, stroke, cerebral damage, cerebrovascular disease, cerebral artery disease, and cerebrovascular accident on PubMed, Embase, Web of Sciences, Cochrane Central Library and Google Scholar. In addition, we also used modifications of the above main keywords to thoroughly search the literature. The major inclusion criteria preferred the literature comprising endothelial progenitor cells, secretome,ischemic stroke, and growth factors.

Endothelial Progenitor Cells

The inability to replicate favorable results obtained in translational studies has spurred stroke research community to explore new therapeutics that can simultaneously and effectively influence major mechanisms implicated in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke (Deb et al., 2010). In this context, cell-based approaches, especially those with endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) have attracted much of the attention (Condon et al., 2004; Di et al., 2009). EPCs are equipped with an inherent capacity to proliferate, migrate and differentiate into few other cells including mature endothelial cells. Considering that endothelial cells constitute the main cellular component of the BBB and help maintain vascular homeostasis through regulation of vascular tone,coagulation and inflammation, replacement of dead or dying endothelial cells by EPCs is thought to be of considerable therapeutic value for patients with ischemic stroke. However,the sparsity of EPCs in circulation necessitates their isolation,characterization and expansion before re-administration as autologous or allogeneic therapeutics.

EPCs were first isolated as a subtype of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Asahara et al., 1997) and later classified into two subtypes, early EPCs which appear after 3–5 days in culture, have spindle-shaped morphology and the late EPCs (also known as outgrowth endothelial cells (OECs))which appear within 2–4 weeks after seeding and display cobblestone morphology (Hur et al., 2004; Bayraktutan, 2019).The OECs express angiogenic characteristics and are fully committed to the endothelial lineage (Medina et al., 2010). A recent study assessing the reparative impact of early EPCs and OECs on endothelial layer of a well-establishedin vitromodel of human BBB, composed of endothelial cells, astrocytes and pericytes, has shown that only OECs can restore integrity and function of BBB by physical incorporation into the site of injury(Abdulkadir et al., 2020). In this regard,in vivostudies proving the safety and efficacy of autologous EPC transplantation also exist (Zhu et al., 2008). In addition to repairing damaged cerebral barrier, EPCs also contribute to neovascularization by modulating the content of their secretome and enhancing cell migration, proliferation and angiogenesis as a consequence(Kalka et al., 2000; Urbich et al., 2003, 2005a; Yamaguchi et al.,2003; Di et al., 2009; Gallina et al., 2015; Felice et al., 2018).As application of EPC-secretome may eliminate the risks associated with transplantation of live cells including emboli,infection and immune incompatibility, EPC-free approach may actually be a better therapeutic option.Table 1summarizes the main benefits affiliated with treatments with EPCsecretome in that the possibility of an off-the-shelf application opens a new avenue in the field of regenerative medicine and deserves to be investigated as a potential therapeutic for ischemic stroke (Ballmoos et al., 2010; Seminatore et al.,2010; Lodi et al., 2011; Rosell et al., 2013; Vizoso et al., 2017).

Analysis of Endothelial Progenitor Cell

Secretome

The term “secretome” is defined as a set of molecules,including of growth factors, chemokines, cytokines, free nucleic acids, lipids and extracellular vesicles, secreted or shed from living cells. The secretome may be stratified into microparticles, apoptotic bodies and exosomes (Tjalsma et al., 2000; Makridakis et al., 2010, 2013; Pavlou and Diamandis, 2010; Skalnikova et al., 2011; Beer et al., 2017).Of these, the exosomes are of particular interest due their ability to control intracellular communications by mediating the transfer of lipids, proteins or RNAs to the target cells.Exosomes are small vesicles that range between 40–150 nm in size (De Jong et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016). EPC-exosomes are surrounded by a bilayer of lipids and have a cup or biconcave morphology which protect them from enzymatic degradation and enable them to serve as transportation cargoes in the body (Yellon and Davidson et al., 2014; Vicencio et al., 2015;Kong et al., 2018). By increasing the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase, EPC-exosome appears to promote the survival,proliferation and tubulogenic activity of endothelial cells(Zhang et al., 2019) while inhibiting vascular leakage in lungs and kidneys (Zhou et al., 2018). Furthermore, EPC-exosome has been shown to inhibit neointima formation and enhance angiogenesis in bothin vitroandin vivosettings like a rodent model of carotid artery injury (Sahoo et al., 2011; Kong et al.,2018). Recent evidence demonstrates that similar to EPCderived exosome, EPC-derived mitochondria also help protect NVU from ischemic damage by incorporating into endothelial cells and increasing intracellular adenosine triphosphate levels and tight junctional tightness (Hayakawa et al., 2018;Borlongan, 2019).

Table 1 |Comparative impact of treatments with EPCs and EPC-secretome

Like mature endothelial cells, EPCs are also able to secret a wide range of substances with different mechanism of action (Table 2). Shotgun proteomics and difference gel electrophoresis studies have identified 82 proteins in the conditioned media of human early EPCs (EPC-CM) which include various members of cathepsin family, proangiogenic substances like chemokine ligand 18, hemoglobin scavenger receptor CD163 and thymidine phosphorylase and few antioxidant enzymes such as mitochondrial superoxide dismutase and hemoxygenase-1 (Urbich et al., 2011). The 71 out of these 82 proteins in EPC-secretome appeared to be different from those of CD14+monocytes and human umbilical veins endothelial cells (Urbich et al., 2011). By culturing cells in growth factor-free medium over a period of 72 hours, Rehman et al. (2003) have found that late EPCs release granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), VEGF, hepatocyte growth factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor as angiogenic growth factors. Additional studies have shown that human EPC-CM also contains chemokines, thromboinflammatory mediators and adhesion molecules. Interestingly,while thrombo-inflammatory mediators such as tissue factors are secreted mainly by early EPCs, those regulate migration and infiltration of monocytes or macrophages, e.g., monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 are mainly released by late EPCs(Zhang et al., 2009). These add further weight to the previous studies indicating that early EPCs and OECs represent distinct EPC populations. Indeed, while cultured early EPCs express many genes linked to immunity and inflammation such as tolllike receptors, human leukocyte antigens and CD14 (Medina et al., 2010), OECs express the markers of senescence and produce greater levels of cytokines. Inflammatory elements such as IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β and IL-1α have been identified as the major facilitators of OEC senescence (Medina et al.,2013). In light of the evidence, treatments with early EPC or OEC secretome should be conducted with care to avoid exacerbation of pre-existing inflammatory response in the ischemic microenvironment.

Possible Mechanisms of Action of Endothelial Progenitor Cell Secretome in Ischemic Stroke

Anti-inflammatory activity

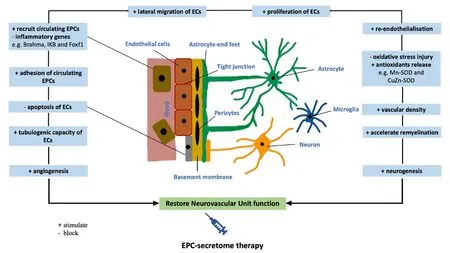

Inflammation, characterized by the exaggerated release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g., IL-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, represents one of the main mechanisms that develop following a cerebral ischemic injury. Stroke patients with localized (cerebral) or systemic inflammation exhibit clinically poorer outcome (Allan and Rothwell, 2001;Fann et al., 2013; Abdullah and Bayraktutan, 2016). Through concurrent regulation of various anti-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory genes such as Brahma, IκB and Foxf1,EPCs attenuate the toxic and apoptotic tendencies of the inflammatory milieu. In support of this notion, co-culture of human EPCs with human endothelial cells has been shown to significantly block the elevations of aforementioned proinflammatory genes during experimental ischemic stroke.Likewise, intracerebral administration of late EPCs into animal model of ischemic stroke (after 4 hours) has also been shown to improve neurological recovery up to 30 days post celltherapy by significantly downregulating the gene expression of Brahma, IKB and Foxf1 in the cortex and striatum (Tajiri et al., 2012; dela Pe?a et al., 2015; Acosta et al., 2019). In accordance with these findings, administration of EPC-CM into a rat model of spinal cord injury has been found to induce functional recovery where attenuation of apoptosis, M1 macrophage activation and IL-6 release along with stimulation of angiogenesis appeared to aid functional recovery (Wang et al., 2018). Similar to these observations, intratracheal administration of EPC-exosome to a mice model of acute lung injury has also significantly reduced chemokine, cytokine and protein concentrations in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid,further supporting the anti-inflammatory and tissue-protective effects of EPC-secretome (Zhou et al., 2019). In another study,reinfusion of a specific paracrine factor, namely thymosin B4 released by embryonic EPCs has diminished infarct size in pigs subjected to myocardial ischemia and enhanced posthypoxic cardiomyocyte survival by moderating post-ischemic inflammatory responses (Hinkel et al., 2008).

Tissue repair and angiogenic regulation

Discovery of an abundance of highly mitogenic cytokines,notably IL-8 and angiogenin in EPC-CM strongly implies that EPC-secretome can readily stimulate the chemotactic,proliferative and tubulogenic capacity of endothelial cells (He et al., 2005). Post-stroke administration of EPCsecretome rich in angiogenic factors may help facilitate vascular repair and suppress neointima formation by inducing proliferation of the resident endothelial cells at the site of vascular damage (Paneni et al., 2016). It is of note here that the process of angiogenesis, involving the activation and migration of endothelial cells, is also regulated by cytokines and chemokines (Gnecchi et al., 2008). Transplantation of OEC-secretome rich in cytokines and chemokines has been coupled to marked increases in the angiogenic capacity of brain BMECs in a mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and inin vitrosettings (Di Santo et al., 2014).Furthermore, greater availability of different growth factors such as VEGF and IGF-1 has also been implicated in increased angio-neurogenesis in the ischemic area of stroke rats treated with late EPCs (Urbich et al., 2005b; Moubarik et al., 2011;Schneller et al., 2019).

Table 2 | Important paracrine factors of endothelial progenitor cell-secretome

Antioxidant capacity

Oxidative stress, emerging from an imbalance between pro- and anti-oxidants, is another major mechanism that can induce or worsen cerebrovascular damage following an ischemic cerebral injury (Allen and Bayraktutan, 2009).Compared to mature endothelial cells, EPCs possess significantly higher total antioxidant capacity. Indeed, greater expression of antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase, Mncontaining superoxide dismutase and catalase enables EPCs to tolerate a certain degree of oxidative stress (Dernbach et al., 2004) and potentiates their vasoreparative and angiogenic capacities in both ischemic and inflammatory settings. For instance, treatments with late EPC-secretome has been shown to mitigate the deleterious effects of oxidative stress on BBB during and after an ischemic stroke (Dernbach et al.,2004) and reduced the extent of oxidative injury in human umbilical veins endothelial cells by augmenting the expression of antioxidant enzymes, Mn- and CuZn-containing superoxide dismutase (Yang et al., 2011).

Migration and tissue invasion

EPCs also regulate cellular chemotaxis by modulating the release of prominent pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF, SDF-1, IGF-1 and hepatocyte growth factor. Increases in VEGF and SDF-1 also facilitate adhesion and recruitment of EPCs to the site of ischemic and non-ischemic damage (Anderson et al.,2015). Similarly, EPC-secretome has been shown to increase mobilization, proliferation and migration of various progenitor and resident vascular cells like cardiac progenitor cells and endothelial cells, respectively. Increased migration of mature endothelial cells to the site of limb ischemia in rats treated with human EPC-CM corroborates this notion (Urbich et al., 2005a).

Apart from growth factors and cytokines, EPCs also synthesize and release many lysosomal peptidases including cathepsin L,cathepsin D, cathepsin H and cathepsin O. Bearing in mind that inhibition of these enzymes, in particular that of cathepsin L,has abated the invasion, incorporation and function of EPCs in a model of hindlimb ischemia (Urbich et al., 2005b), specific targeting of these peptidases may prove to be instrumental in controlling the recruitment of EPCs to the site of injury. It is possible that EPC-secretome supplemented with cathepsin L may substantially induce homing and incorporation of circulating EPCs to the site of ischemic cerebral injury.Figure 3summarizes potential mechanism of action of EPC secretome on NVU during and after ischemic stroke.

Key Mechanisms Associated with Modification of Endothelial Progenitor Cell Secretome

Hypoxia is regarded as the main element that can enhance the migratory and angiogenic capacities of transplanted cells(Wei et al., 2012; Morancho et al., 2013). As exposure of EPCs to hypoxia promotes secretion of a series of growth factors,notably VEGF, VEGF-D, PDGF-BB, epidermal growth factor,basic fibroblast growth factor as well as angiogenin, leptin and thrombopoietin, it is likely that CM obtained from EPCs subjected to hypoxia can augment the regenerative potential of native and transplanted progenitor cells (Di Santo et al.,2014). Indeed, such treatment has recently been shown to induce mobilization of EPCs from bone marrow and led to increases in hindlimb blood flow and capillary density while inhibiting apoptosis of mature endothelial cells (Di Santo et al., 2009). Furthermore, application of hypoxic EPCCM entrapped in polymer-based nanoparticles, carriers for controlled release of EPC secretome, has also been shown to increase blood perfusion and capillary formation in ischemic limb model (Felice et al., 2018). EPCs grown under hypoxic conditions have been shown to secrete 647 proteins. Of these,83 appear to be differentially regulated compared to the cells grown under normoxic conditions. While the expression of 17 of these 83 proteins, mostly angiogenic factors including protein S100 family, apolipoprotein E, protease inhibitors are upregulated by hypoxia, the expression of 12 proteins, notably dermcidin, trypsin-1, cystatin-C and calcium-binding protein 39 appear to be downregulated (Felice et al., 2018).

Inflammation or inflammatory reactions can also influence the number and functionality of EPCs. Inflammatory factors such as GM-CSF and SDF-1 enhance mobilization of EPCs from bone marrow (Takahashi et al., 1999; Tousoulis et al., 2008).For example, the increases seen in number of functional late OECs mirrored increases in plasma levels of VEGF, SDF-1 and IL-8 in burned patients within the first 24 hours of hospital admission (Rignault-Clerc et al., 2013). Another study focusing on the mobilization of EPCs in two different groups of patients with acute vascular injury emerging from burns or coronary artery bypass grafting has also revealed substantial increases in circulatory EPC numbers and coupled these to significant increases in plasma VEGF and cytokine levels (Gill et al., 2001).These findings suggest that enrichment of EPC-secretome by exposure to inflammatory stimuli inin vitrosettings may potentiate its therapeutic impact inin vivosettings through recruitment of resident EPCs from bone marrow to the site of ischemic injury.

Figure 3| Possible mechanism of action of EPC secretome on restoration of neurovascular unit during or after an ischemic stroke.

As indicated above, oxidative stress radically contributes to the pathogenesis and progression of ischemic stroke.Genetic manipulation of factors associated with the release or neutralization of ROS is therefore likely to influence the content of EPC-secretome and its therapeutic efficacy.Mammalian adaptor p66Shc and JunD, a member of the activated protein-1 family of transcription factors which modulate mitochondrial ROS production and vascular cell senescence have attracted some attention in this context.Indeed, compared to OECs obtained from young donors, OECs of old subjects express significantly higher levels of p66Shc(pro-oxidant) and the lower level of the activated protein-1.However, genetic manipulation of OECs isolated from elderly donors through silencing of p66Shc or overexpression of JunD has been shown to attenuate age-driven ROS generation by reinstating a balance between pro-oxidant and anti-oxidant enzymes and enhance SDF-1 expression in conditioned media(Paneni et al., 2016).

Therapeutic Potential of Endothelial Progenitor Cell Secretome

Considering that proteins secreted into conditioned media inin vitroconditions mimicking an ischemic injury are likely to be representative of those found in circulation following a cerebral ischemic episode, their analysis and accurate identification are of profound diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic importance(Stastna and Van Eyk, 2012). In light of the reports illustrating post-ischemic increases in circulating numbers of EPCs, it is safe to propose that similar increases in the synthesis and release of constituents that make up EPC-secretome may also go up which in turn substantiate their diagnostic value (Sobrino et al., 2007). While regenerative potential of EPC-secretome is somewhat well-documented in experimental settings, to our knowledge there is currently no clinical study that has assessed the putative therapeutic role of EPC-secretome after an ischemic stroke. In fact, phase I and phase II clinical trials of intravenous transplantation of allogenic mesenchymal stem cells for patients with chronic ischemic stroke (> 6 months of onset) have been shown to be safe and associated with significant behavioral gain over a 12-month follow up (Levy et al., 2019). As the microenvironment affecting the NVU after an ischemic stroke is under persistent change (Liao et al.,2017), while designing prospective clinical trials, the timing of treatments with EPC-secretome is an important factor to take into consideration. Transplantation of EPCs or EPCsecretome rich in VEGF, PDGF-BB and fibroblast growth factor into a mouse model of ischemic stroke, within 30–32 hours of ischemic stroke, has been shown to enhance capillary density in the peri-infarct areas and improved functional strength of forelimbs. The improvements in functional aspects remained noticeable at 2 weeks following ischemic injury and were largely attributed to the appearance of additional blood vessels in the peri-infarct areas (Rosell et al., 2013).Intravenous injection of EPCs into a rodent model of transient ischemic stroke 24 hours after the occlusion of middle cerebral artery also led to a significant functional recovery within two weeks. Given that the direct incorporation of EPCs into rat neovasculature could not be visualized in this study, functional improvements observed might actually be due to the paracrine effects of EPC-secretome (Moubarik et al., 2011). A relevant study testing the angiogenic capacity of early (within 1 hour of stroke) and late (48 hours after stroke) administration of VEGF,a key component of EPC-secretome, to a rodent model of ischemic stroke has generated some interesting findings in that while the former approach compromised the integrity of the BBB and promoted hemorrhagic transformation in the focal ischemic lesions, the latter approach enhanced angiogenesis in the ischemic penumbra and significantly improved neurological recovery. Taken together these findings imply that future therapeutic strategies considering exogenous administration of EPC-secretome should pay a very close attention to the treatment start time and adjust the concentration of EPCsecretome according to the phase of ischemic stroke;hyperacute, acute, subacuteversuschronic (Zhang et al.,2000).

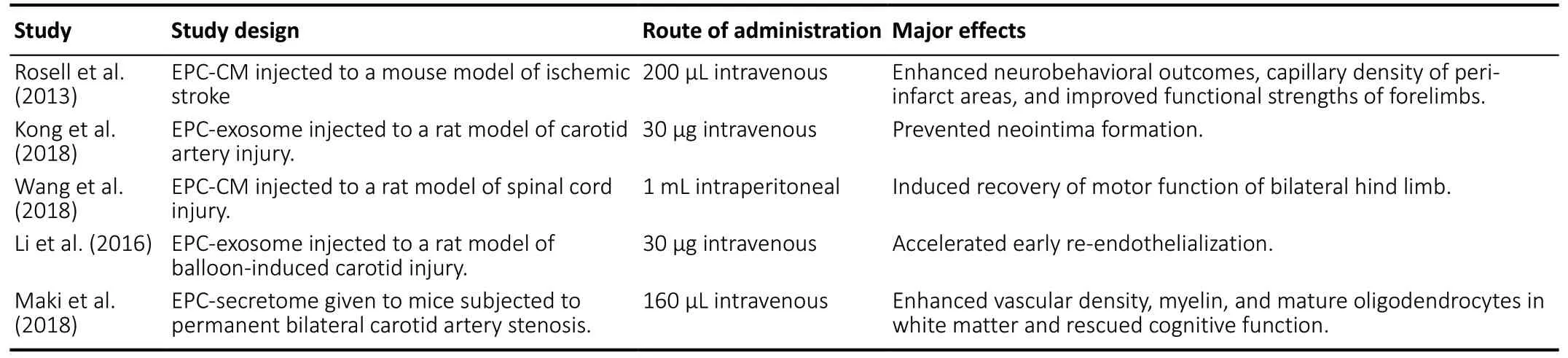

Similar to the beneficial effects observed after ischemic stroke,EPC-derived factors have been shown to protect cultured cortical neuronal progenitor cells from a metabolic injury induced by glucose and serum deprivation (Santo et al., 2020).Again, transplantation of EPCs to a mice model of traumatic brain injury led to elevations in neovasculogenesis and neurological recovery. Here, stimulation of axonal outgrowth of neurons along with increased proliferation, survival and recruitment of resident EPCs to the site of ischemic brain injury by key constituents of EPC secretome, namely VEGF,SDF1 and proangiogenic cytokines, was thought to play a critical role (Zhang et al., 2013). EPC secretome-mediated suppression of inflammation alongside the regulation of angiogenesis, functional recovery and axonal regeneration has also been implicated in neuroprotection in a rat model of spinal cord injury (Wang et al., 2018). Furthermore,intravenous administration of EPC-secretome to mice at 24 hours and 7 days of permanent bilateral occlusion of carotid arteries has also been associated with promotion of vascular density and protection of cognitive function in a mouse model of white matter injury following prolonged cerebral hypoperfusion (Maki et al., 2018). In light of these studies, it is reasonable to suggest that administration of EPC-secretome to patients with ischemic stroke beyond the hyperacute phase of the disease may be beneficial.Table 3summarizes the major benefits of EPC-secretome in pre-clinical settings.

Table 3 |Therapeutic effects of EPC-secretome on various conditions

Conclusion

It is evident that EPCs secrete a vast range of substances with differing function. Evidence gathered from an increasing number ofin vitroandin vivostudies suggest that these factors may help repair the damaged neurovasculature after an ischemic stroke by inducing mobilization, proliferation,migration and homing of resident or circulatory progenitor cells to the damaged vasculature. Available evidence also indicates that timing of post-stroke administration of EPCsecretome is of crucial importance to improve neurological outcome and to prevent hemorrhagic transformation.However, well-thought future studies scrutinizing the therapeutic potential and efficacy of EPC-secretome in laboratory, translational and clinical settings are required before a cell-free treatment regimen can become a therapeutic possibility for patients with ischemic stroke.

Author contributions:Literature retrieval and manuscript preparation:MA; manuscript review and review guiding: RRA; review conception and manuscript editing: UB. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial support:None.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2021年8期

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2021年8期

- 中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its related enzymes and receptors play important roles after hypoxic-ischemic brain damage

- Environmental enrichment combined with fasudiltreatment inhibits neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 region and ameliorates memory deficits

- Regulation of neuronal bioenergetics as a therapeutic strategy in neurodegenerative diseases

- The neuroimaging of neurodegenerative and vascular disease in the secondary prevention of cognitive decline

- Induced pluripotent stem cell technology for spinal cord injury: a promising alternative therapy

- The interaction of stem cells and vascularity in peripheral nerve regeneration