Investigation of the stability and hydrodynamics of Tetrosomus gibbosus carapace in different pitch angles *

Mahyar Malekidelarestaqi, Alireza Riasi , Hadi Moradi , Mohammad Samadpour

1. School of Mechanical Engineering, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2. Intelligent Systems Research Institute, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea

3. School of Electrics and Computer Engineering, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

4. School of Mechanical Engineering, Amirkabir University of Technology, Tehran, Iran

Abstract: In this paper, stability properties of Tetrosomus gibbosus have been experimentally and numerically studied in pitching movements. This fish lives in southern offshores of Iran. Boxfishes usually live in extremely turbulent parts of seas and oceans, with high stability and maneuverability that has caught the attention of scientists. Their body shape let them swim with a quite rapid speed.Studies on Boxfishes have had influences on automotive and marine industries. The CAD file of the boxfish was created using optical CMM. Also a model was built and tested in a subsonic wind tunnel and a numerical study was conducted in virtual wind tunnel. The experimental results are consistent with the numerical ones and also support the findings of other studies on similar boxfishes. These results show that the flow around the fish, which is a consequence of its body shape, tries to maintain the stable position of the fish by resisting against the external force tilting the fish from its stable horizontal posture. The ventral and dorsal keels of the boxfish generate column-like vortices in horizontal direction which play an imperative role in maintaining the stability of the fish.

Key words: Boxfish, Tetrosomus gibbosus, humpback turretfish, hydrodynamic stability, experimental fluid mechanics, bio-inspired engineering

Introduction

Bio-inspired Engineering or Biomimetics has been a new trend in the past two decades in which the biological organisms are studied and the inspired ideas and products are developed from them. Boxfishes have been one of these biological organisms which show unique performance and characteristics in turbulent conditions such as those existing in coral reefs. The world of fish is widely diverse and each fish has evolved to adapt to its habitat. Boxfishes are highly energetic rigid-bodied marine fishes that live predominantly in shallow-water and tropical reef environments. They are median/paired fin (MPF)swimmers and despite their bulky appearance (most of their bodies is encased in a bony carapace), boxfishes are remarkably stable and maneuverable swimmers[1-2].They are able to maintain smooth swimming trajectories with minimal pitching, rolling, and yawing recoil even in highly turbulent waters[3]. Moreover,they are capable of swimming rapidly (even over 6 times body lengths per second for some species), can spin around with a minimal turning radius, and can hold precise control of their positions and orientations.Studies of Hove and Bartol et al. revealed that keel contours and other physical characteristics of the rigid carapace produce spiral vortices that are central to the boxfishes’ sophisticated self-correcting mechanism[4-6].

Based on Weihs’ definition[7], stability is achieved in aquatic environment, when a random or forced perturbation in the conditions surrounding the fish results to forces or couples that tend to reduce the perturbation and return the fish in its original stable state. Maneuvers are the most important behavior of fish, affecting all aspects of their lives and are executed by the whole body and fin surface, but understanding of their mechanisms and performance is incomplete[8]. Animals can manipulate flow around their body both passively and actively. Passive mechanisms rely on structural and morphological components of their body while in active mechanisms animals use appendage or body muscles to directly generate wake flow structures[9]. Smith and Caldwell[10]state: “Locomotion control and vortex generation mechanisms include the development of specific morphological features such as the keels and ridges associated with the carapace of tropical boxfish”.Until 2002 Boxfishes were just known as rigid-body,multi-propulsor swimmers that exhibit unusually small amplitude recoil movements during rectilinear locomotion. Mechanisms producing the smooth swimming trajectories of these fishes were unknown.Therefore, Bartol et al.[11]studied the roles that the carapaces of boxfishes play in generating this dynamic stability. Exact models of four distinct species of boxfishes (scrawled cowfish, buffalo trunkfish,smooth trunkfish and spotted boxfish) were constructed and flow patterns around each model were investigated using digital particle image velocimetry(DPIV), pressure distribution measurements on the carapace, and force balance measurements on the whole body. DPIV results showed that the keels of all boxfishes generate longitudinal vortices that vary in strength and position with the angle of attack. In areas where attached concentrated vorticity were detected,low pressure was also detected at the carapace surface.Predictions of the effects of the first two methods were consistent with forces and moments measured using the force balance. The three experimental approaches indicated that the ventral keels of all boxfishes, and in some species also the dorsal keels,generate self-correcting forces for pitching motions. In their next work, Bartol et al.[5]have studied the role played by the bony carapace of the smooth trunkfish,Lactophrys triqueter, in generating trimming forces that self-correct for instabilities. The three aforesaid complementary methods were used to investigate the flow patterns, forces and moments on and around smooth trunkfish models positioned at both pitching and yawing angles of attack, which illustrate self-correcting forces by the carapace of this fish for both pitching and yawing motions. In their next paper,Bartol et al.[4]showed that other three types of tropical boxfishes with different carapace shapes have similar capabilities. The ventral keels of all three fishes produced leading edge vortices (LEV) that grew in circulation along the bodies. These spiral vortices formed above the keels, in positive pitch angles, and below the keels, in negative ones, and increased in circulation as pitch angle deviates further from zero,producing suction areas at posterior parts of the boxfishes creating self-correcting moments. The same procedure also happens in yaw angles of attack.Although other features of the carapace also affect flow patterns and pressure distributions in different ways, the integrated effects of the flows were consistent for all forms. In their most recent work on boxfishes[12], Bartol et al. pursued their studies on live,actively swimming boxfishes (Spotted boxfish and smooth trunkfish) and obtained similar results to their previous studies, in which the little difference attributed to the differences between the real and model fish. They also measured the vortex strength of both the model and live fish.

It was only after the researches of Bartol et al.that boxfish body shape; which is the cause of their ability of hover, maneuver and stability; has greatly caught the attention of scientists in the fields of robotic fish, autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV)and Micro Underwater Vehicle (MUV). However,most of their work was on controlling mechanisms and fin performances. They started using boxfish as an inspiration for their shape designs. Deng and Avadhanula[13]started bringing the knowledge of boxfish in hydrodynamic and locomotion fields, to the robotic world, by a biomimetic MUV with oscillating fin propulsion. Then Kodati et al.[14-18]studied the tail fin and effects of body shape on stabilizing selfcorrective vortices, using CAD/CAE tools and Fluidflow software. They used the results of their studies on two species of boxfishes to design and fabricate a Robotic Boxfish, named Micro Autonomous Robotic Ostraciiform (MARCO). Hu et al. used boxfish shape in their vision-based autonomous robotic fish[19]. Pi[20]mimicked the pectoral fin movement of boxfish in her MUV. Lachat et al.[21-22]introduced their maneuverable fish robot with three actuated fins which was inspired by boxfish. In more recent years, since 2013, Wang et al.[23-28]are working in this field to mimic the exact control attitude of a boxfish-like robot in gait and locomotion. Beside the field of robotic fish, the carapace of boxfish was used by automotive engineers and scientists as a source of inspiration for the design of low drag automobiles with high stability[29-30].

A species of boxfish which has never been studied before, i.e., Tetrosomus gibbosus, was investigated in this paper by experimental and computational tools, and its hydrodynamic features and stability characteristics in pitching movements have been studied. Unlike other boxfishes which live in tropical environments, Tetrosomus gibbosus is a native of Kharg Island located 25 km off the south coast of Iran,Indian Ocean, Mediterranean and Black Sea, etc..Figure 1 shows the boxfish that we used for this study,which was preyed in Kharg Island.

1. Materials and methods

1.1 Geometry modelling

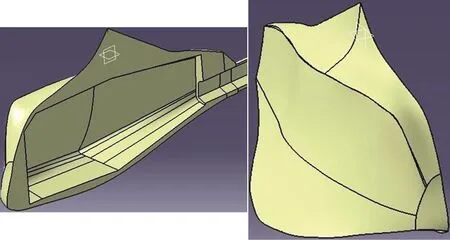

The geometry of the model was built based on a real humpback turretfish. Using optical coordinate-measuring machine (CMM), a 3-D image of the fish was extracted in point cloud form, from the specimen.A commercial software was used for modelling the computer aided design (CAD) file of the fish.Considering the symmetrical structure of the fish, all the modeling was done on one half of it. A prototype was designed to preserves the necessary similarity with the model, which led to preserving the physical characteristics of the real fish. Two pictures of the CAD model are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1 (Color online) Pictures of Tetrosomus gibbosus preyed in Kharg Island, Persian Gulf (The eyes are artificial.)

Fig. 2 (Color online) Schematics of CAD model in the software

1.2 Experimental study

1.2.1 Model fabrication

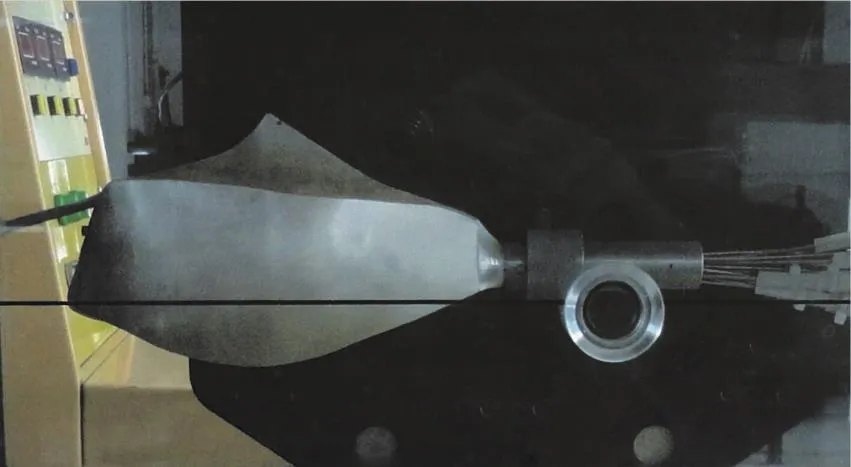

The physical model of the fish was made of Aluminum using a SIEMENS 740 controller computer numerical control (CNC) machine. To be able to measure the pressure on the surface of the model, 19 ports have been placed on the model, Fig. 3. The two symmetric parts were placed next to each other to make one complete model of the fish.

1.2.2 Experimental setup

Experiments of this study were done in a subsonic wind tunnel with a three component force measurement balance. So the forces and the moments were available for measurements using the proper equations. The wind tunnel has a cross section of 460 mm×460 mm, and the user can change pitch angle of attack.Figure 4 shows the model in the wind tunnel. Pressure of the ports on the surface of the model was measured with manometer with the accuracy of 2 mm of water.To calculate the wind speed and consequently Reynolds number, reference pressure difference (RPD)between two specific ports on the conic part of the wind tunnel was measured using a tilted manometer with the accuracy of 1 mm of water was used.

Fig. 3 (Color online) The Aluminum model built in CNC machine

Fig. 4 (Color online) The fish model in the wind tunnel

The experiments were done in four RPDs which lead to four velocities and in turn four Reynolds numbers. Considering the maximum speed of the living boxfish in the water being equal to 6 times of the total length per second (based on Ref. [1]), the Re would be about 2.4×105. Our experiments were performed for four Reynolds numbers varying from 169 000 to 241 850 and almost identical results were reached for all the four Reynolds numbers. Therefore,only the results of the maximum Reynolds number are presented here. The length parameter in the Reynolds equation is measured from the head to the caudal peduncle of the fish and is equal to 200 mm. The model and the real fish have the same size. The three-component balance system of the wind tunnel reports aft, Fore (components of lift force) and drag.The required equations for deriving all the other desired values from the wind tunnel balancing system are introduced here

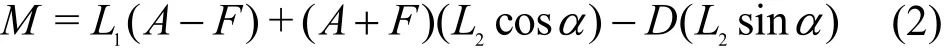

which A, F are the aft and fore components of the lift load (L). The equation of the corrective moment is

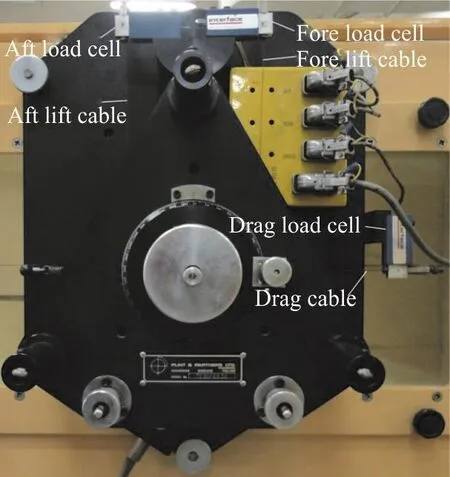

in which M is the pitching moment,1L is the distance between aft and fore load cells’ connection points on the force balance and L2is the distance between the center of mass of the model and the center of the force balance (the middle point of the two load cells connection points), α is the angle of attack and D is the Drag load in Fig. 5(a). Figure 5(b) is a picture of three component balance system.

Fig. 5(a) A schematic of the placement of load cells and the model on balancing system

Fig. 5(b) (Color online) A picture of the balancing system

The required equations for calculating lift, drag,moment and pressure coefficients are as follows:

Lift coefficient

Drag coefficient

Moment coefficient

Pressure coefficient

where L is the length from head to the end of the caudal peduncle, Asis the maximum frontal area,Apis the planform surface area of the ventral region and C is the width of the fish.

1.3 Numerical simulation

Fluid simulation studies were carried out to detect the pressure distribution, vorticity generation and distribution, and generally the characteristics of the flow around the fish that could not be measured with the experimental approach. To this end, the foresaid CAD model was placed in a virtual wind tunnel with the proper size so that the walls wouldn’t affect the flow around the fish. In order to lower the computational cost of meshing and solving process and increasing the accuracy of solution in regions close to the body, the whole field area around the fish was divided into two distinct areas, named Far-field and Fish-field, with coarser and finer meshes,respectively. Then the meshing process took place on the whole area in the virtual wind tunnel. Changing Alpha (pitching angle) was also possible in the computational solution. The solution verification was checked through grid independency. Also the+y of all the solutions were always about 60 on the body of the fish, which is an acceptable value in solving fluid flow using shear stress transport (SST) turbulence model[31]. Initially a simulation on the whole body was done in order to ensure that the results of the left and the right half of the fish are similar due to the symmetrical geometry of the fish. After getting similar results, all the computational simulations were performed on one symmetric half of the model to reduce computational cost. All the initial and boundary values and settings of the solution were set based on the real values from the experimental setup.The problem is computationally solved in steady state mode by solving the governing equations, i.e., the continuity, momentum and the SST turbulence equations. Due to low air speed in our experiments,the flow is incompressible. It is also considered isothermal, because the changes in the temperature of the air are negligible.

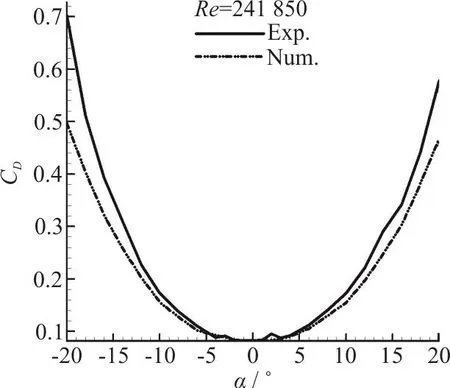

Fig. 6(a) Validation of drag coefficient

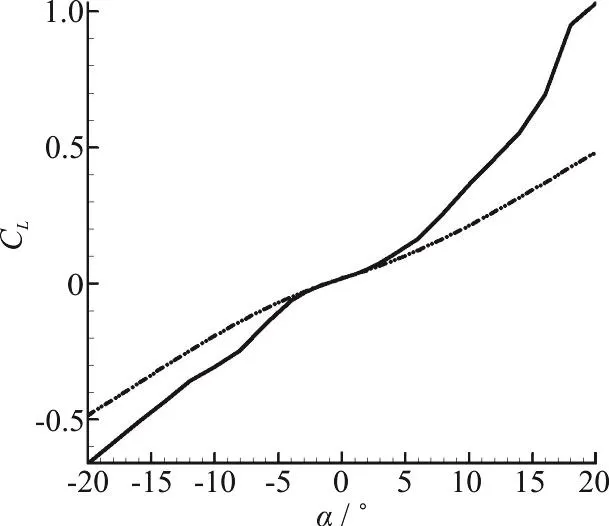

Fig. 6(b) Validation of lift coefficient

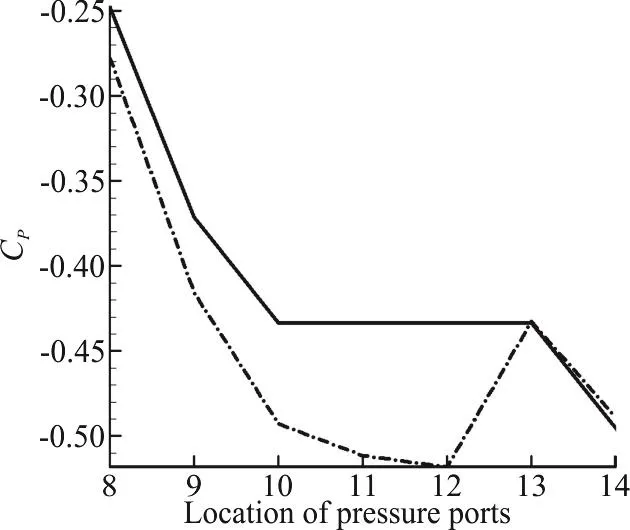

Fig. 6(c) Validation of pressure coefficient at 0° angle of attack for ports of the middle section

1.4 Numerical simulation validation

The validity of the two sets of results (experimental and computational) should be confirmed at first, therefore lift and drag plots are presented here.The results of all four Reynolds numbers in our experimental tests were in consistency with each other.Consistency was seen among the results of numerical modeling for various Reynolds numbers too. Therefore only the results of the maximum Reynolds number are presented here for comparison. Figs. 6(a),6(b) are illustrating the drag and lift coefficients for different angles of attack. It can be seen that the results of the force measurements are only acceptable in the range of -10° to +10°. And Fig. 6(c) shows the validation of pressure coefficient at 0 degree angle of attack for a selected section of pressure ports. The accuracy limitations of the measuring instruments,vibration of the model in the wind tunnel, the presence of connection rod and pressure measuring tubes in our experiment (which are not modelled in our simulations) resulted in larger discrepancies for greater values of angle of attack, especially for the lift plot.

The maximum error values for lift and drag coefficients in the range of -10°-+10° angles of attack,which is recognized as the acceptable range in these experiments, are 41%, 11%, respectively. And the maximum error value for pressure coefficient in selected port locations at 0° angle of attack is 19%.

2. Results and discussion

All the experimental and numerical results,including pressure measurements, force measurements and status of vorticity around the fish are presented and discussed in following sections.

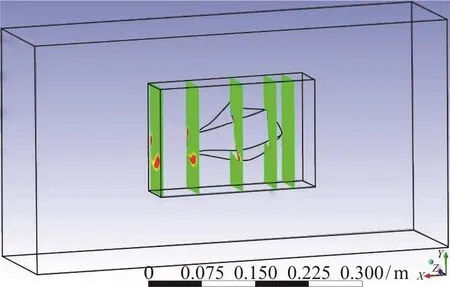

Fig. 7 (Color online) Location of the five planes which the study of vorticity and pressure contours took place on them

2.1 Vorticity and pressure contours

In this part, vorticity and pressure contours for two different angles of attacks, +10°, -10°, in five parallel cross sectional planes perpendicular to the flow direction are presented, so that the generation and behavior of twin spiral vortices can be observed.The five planes are shown in the Fig. 7. The first plane is in front of the head of the model, the second one is at the eye ridge (the first transect of pressure ports),the third one is at the maximum width of the model(the second transect of pressure ports), the fourth plane is at the end of the model, and finally the fifth one is at the downstream with a distance of approximately 0.07 m.

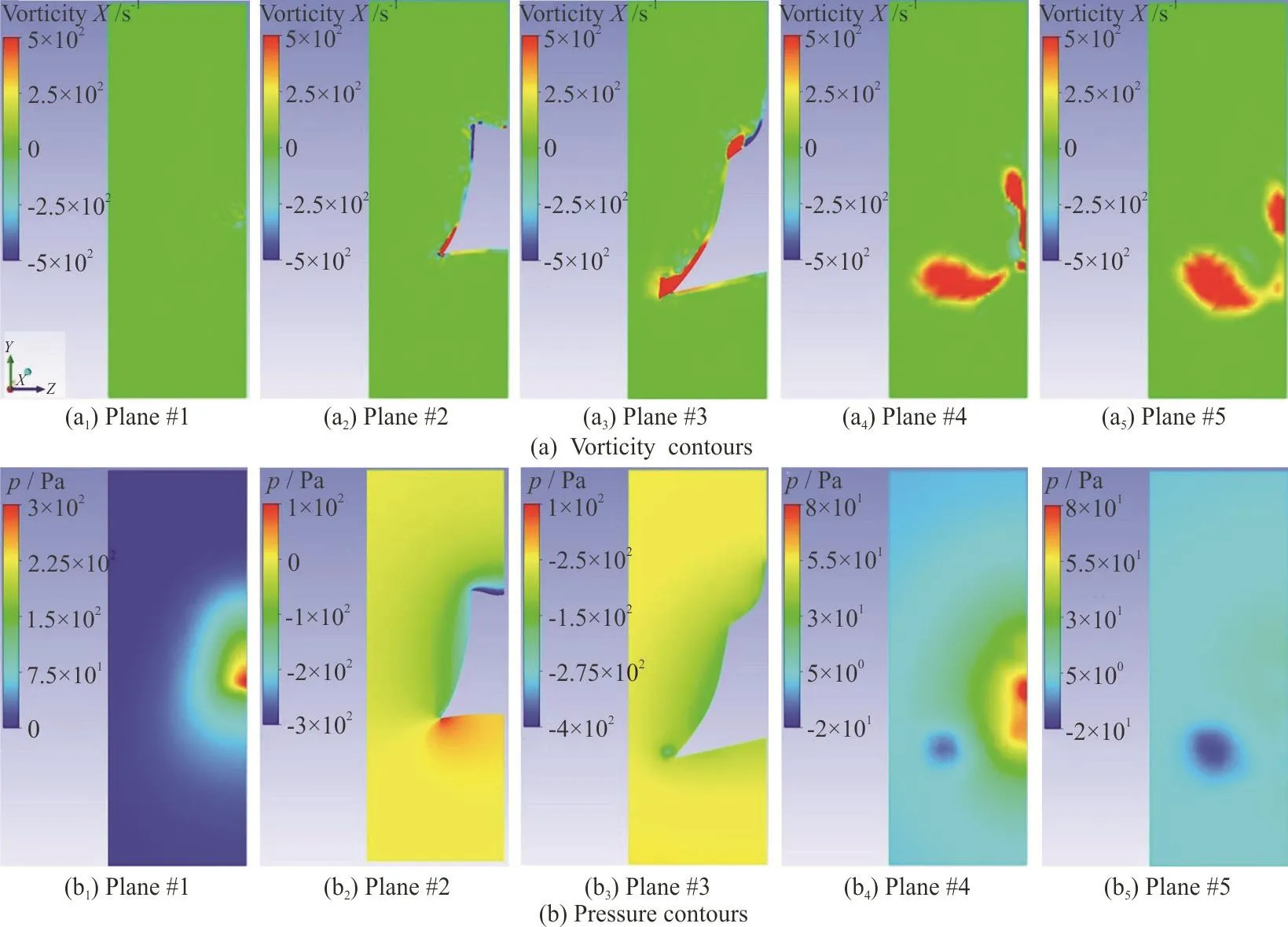

Fig. 8 (Color online) Vorticity and Pressure contours in five parallel planes at +10° angle of attack in the Re of 241 850

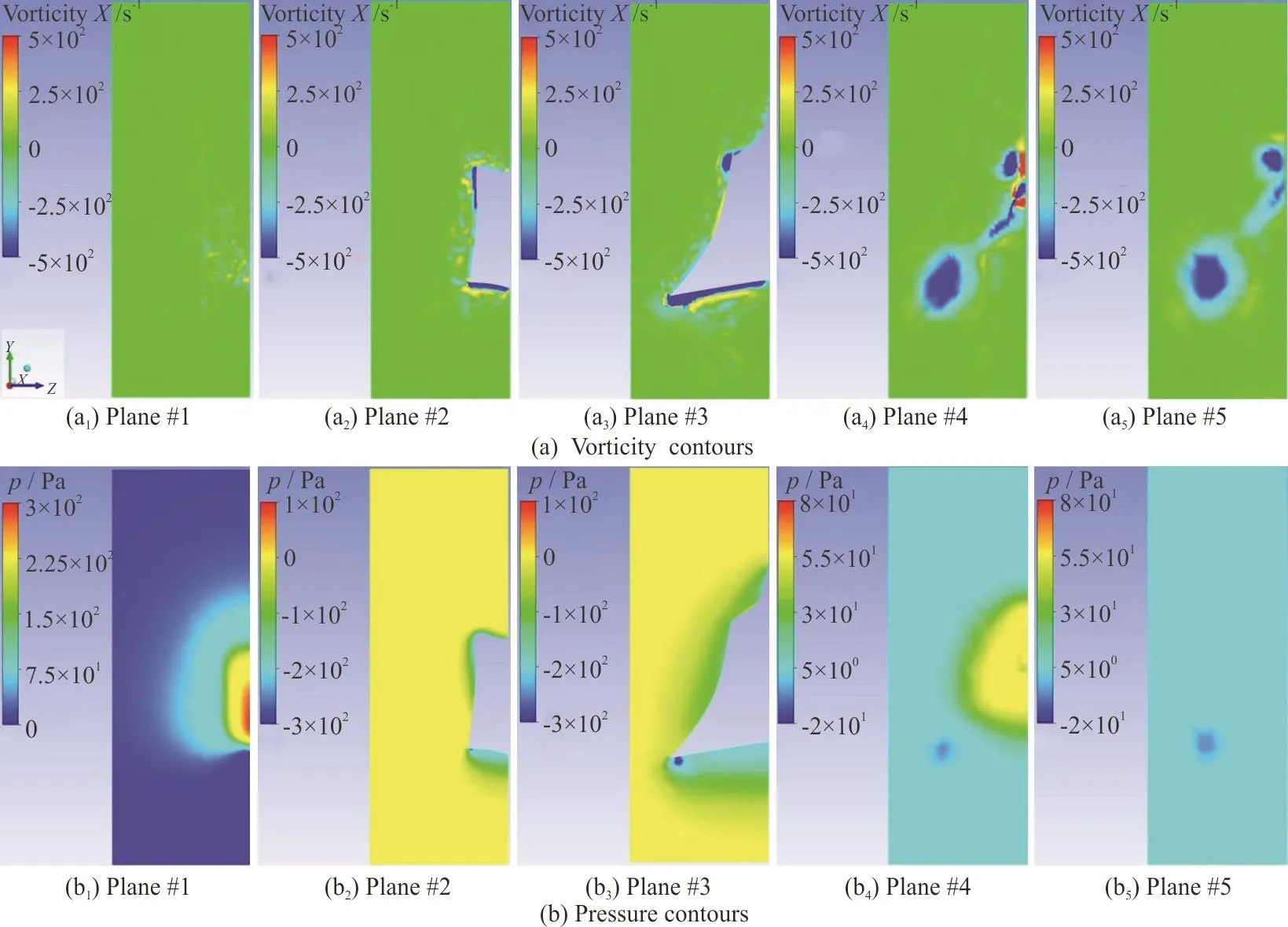

Fig. 9 (Color online) Vorticity and pressure contours in five parallel planes at -10° angle of attack in the Re of 241 850

Vorticity and pressure contours in the aforementioned five planes are presented in Figs. 8, 9. These contours belong to +10°, -10° angles of attack,respectively. Then, the general view of the generated vortices can be seen in the next two figures, Figs. 10,11.

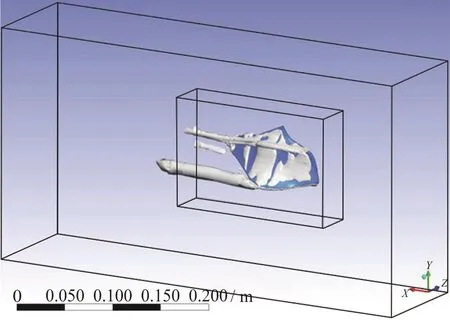

Fig. 10 (Color online) The general view of vortices around the fish at +10° angle of attack in the Re of 241 850

Fig. 11 (Color online) The general view of vortices around the fish at -10° angle of attack in the Re of 241 850

These sectional planes and the two overviews show the process of generation and growth of the twin spiral vortices induced by the keels. In the coming sections it will be demonstrated why they are called self-corrective vortices. These vortices are generated because of the presence and posture of the dorsal and ventral keels of the boxfish. Based on the angle of attack and the Reynolds in which the fish is swimming,the flow and pressure distribution around and on the surface of the fish are affected. Their size and their starting point vary with the angle of attack. More deviation from zero in both positive and negative directions results in a stronger vorticity, and therefore more pressure drop on the location of these vortices.The starting point of the dorsal vortices is around the eye ridge and for ventral vortices it is located on a point between eye ridge and the maximum width transects. At positive angles of attack the ventral vortices are above the keel and start to leave the body approximately at maximum width, while the dorsal vortices start departing a little closer to the eye ridge.So, the pressure drop by ventral vortices would be detected by pressure sensors at second intersect, but the pressure drop induced by the dorsal vortices would not be sensed. In negative angles of attack the ventral vortices are formed under the keel and depart the body approximately at the maximum width transect, while dorsal vortices remain attached to the body, roughly on the whole carapace, so pressure ports would sense the pressure drop induced by dorsal vortices.

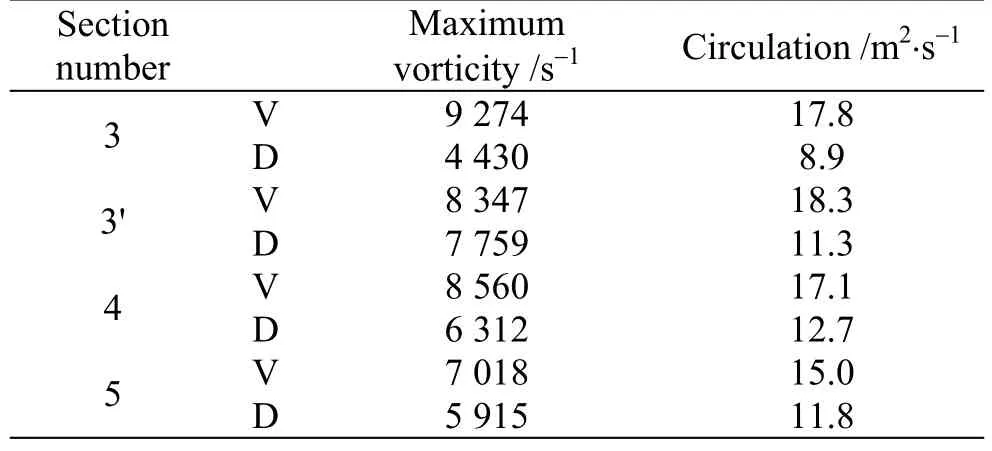

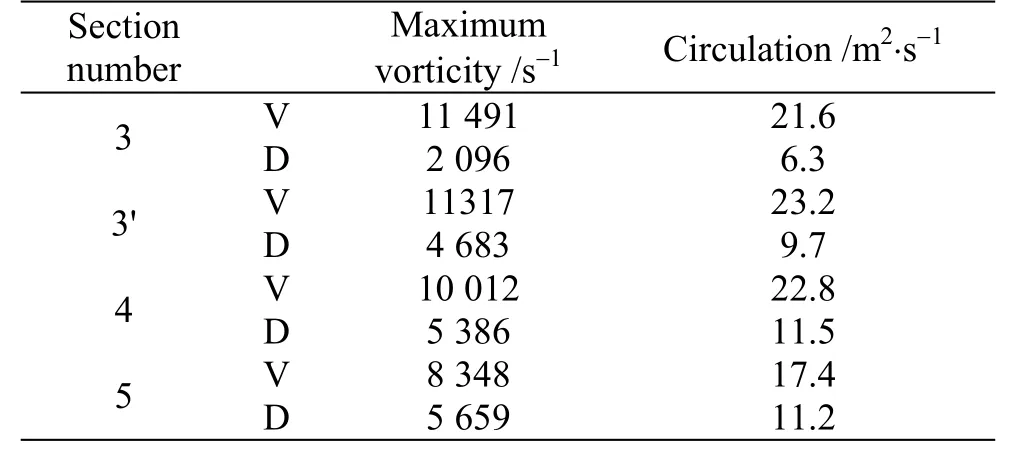

Tables 1, 2 are showing the circulation value and the absolute value of the maximum vorticity in different cross sectional planes along the body in +10°,-10° angles of attack. It should be noted that these results are presented at cross sectional planes posterior to the maximum width of the body, because vortices are not generated completely anterior to it. The planes number 3, 4 and 5 are the same planes in Fig. 7 and the plane number 3′ is placed at the middle of the planes 3, 4. The results in this plane are presented for more clarification.

Table 1 The circulation value and absolute value of maximum vorticity for ventral and dorsal keels in different cross sectional planes along the body at +10°angle of attack

Table 2 The circulation value and absolute value of maximum vorticity for ventral and dorsal keels in different cross sectional planes along the body at -10°angle of attack

The sign of the maximum vorticity is positive in positive angles of attack, and is negative in negative angles of attack. Based on the contours and tables, the ventral vortices are a little stronger and consequently will produce more minus pressure or suction. As the pitch angle deviates further from zero in positive direction, the vortices which in this state were generated and grew above the keels, mainly become stronger in terms of circulation and absolute vorticity.In the case of pitch angle deviation in negative direction, the vortices that were created under the keels become stronger too, but with opposite circulation. As it is clear from the results, the ventral vortices have a little larger values than dorsal vortices,leading to more pressure drop. In both states of positive and negative pitch angles, suction areas at the posterior parts of the fish (behind the center of the mass) are created. As it is mentioned before, in positive pitch angles the spiral vortices incurred by ventral keels are above them and in negative pitch angles are under them, so in both situations suction areas force the posterior of the fish and make a pitching moment to get it back to its horizontal stable posture. In short, in positive angles of attack, a head-down moment and in negative angles of attack, a head-up moment occurs, which are the result of spiral vortices, or as we call, the self-corrective vortices.

2.2 Pressure measurements plots

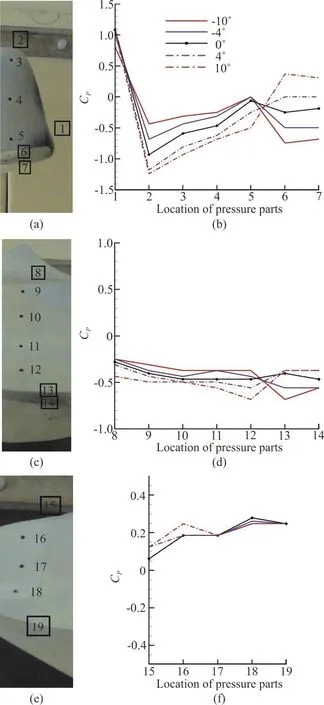

In this study the ports have been created on three cross sections which are located on the eye ridge, the maximum width, and the farthest available section near the caudal peduncle of the model. The 19 ports and their indication numbers are shown in Fig. 12.Figure 12 shows the Cpas a function of location for all the 19 ports on the model in three transects for two negative, two positive and zero angles of attack. The results which are shown here are measured at Re =241850.

As it is clear in the plots, the port number one which is expected to be near the stagnation point, has a pressure coefficient of about 1, which is acceptable.In negative angles of attack, the ports on ventral part of the model (points 6, 7, 13, 14 and 19) are not facing the flow directly, so they sense less pressure and have smaller values of Cp. There are no spiral vortices generated at the first transect. So, no changes in the pressure as a result of these vortices were sensed. In positive angles an increase, and in negative angles a decrease in pressure are seen in ports 6, 7, based on facing or not facing the streamlines. But in second transect the vortices are generated.

Fig. 12 (Color online) Pressure coefficient versus measuring port location at different pitch angles in a Re = 241850 : (a)location of measuring ports at first transect, (b) p C at pressure ports 1-7 in different angles of attack, (c) location of measuring ports at second transect, (d) p C at pressure ports 8-14 in different angles of attack, (e) location of measuring ports at first transect, (f) p C at pressure ports 15-19 in different angles of attack. Remark:The 19 ports are placed on different surfaces of the model,some of them are not visible in a 2-D picture from the selected angle that the picture was taken, so in (a),(c) and (e), the number indicating the approximate location of these points are distinguished with a rectangle around them

As the angle of attack becomes more negative,port number 2 faces more directly to the streamlines,causing the pressure to increase. While in positive angles of attack, bigger values of pitch angle results in lower amounts of pressure coefficients. The analysis of pressure coefficient in port number 8 is just like port number 2 in negative angles of attack, but is different in positive angles of attack due to the presence of vortices. As the model deviates from zero in positive direction, the attached dorsal vortices become greater, causing bigger pressure drop on this port. At the second transect, the ventral vortices are attached to the keel, clearly illustrated by the behavior of pressure at ports 12, 13. As it is stated earlier, at positive angles of attack, the attached vortices are above the ventral keels and at negative angles they are under the keels. So, in positive angles of attack, a pressure drop at port 12, and in negative angles, a pressure drop at port 13 can easily be seen.

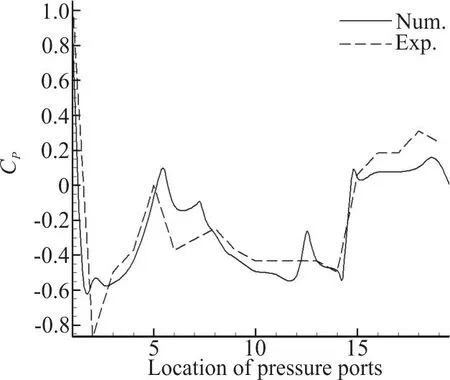

Fig. 13 Comparative plot of pressure coefficients for experimental and numerical results in Re = 241850 at the 0° angle of attack

As it is shown in Figs. 8-11, at the third transect the vortices are detached from the carapace, and just port 15 located on dorsal keel can sense the pressure drop by the dorsal vortices, resulting in lower amounts of Cpboth in positive and negative pitching angles of attack.

Figure 13 plots Cpas a function of location for both experimental and computational results. It should be mentioned that in the computational simulation,new locations for pressure measurement were defined in addition to the port locations on the surface of the constructed model in order to obtain more precise understanding of the flow around the fish. Figure 13 shows that the trends of experimental and computational results are similar, and the differences between the results are contributed by the differences between constructed model and the CAD model, such as the thickness of the keels, the roughness of the surface and also device measuring errors. The added pressure measuring points in the computational sets of results are also a source of difference between two plots.

Now the sun set; the owl flew into a bush, and immediately an old, bent11 woman came out of it; she was yellow-skinned and thin, and had large red eyes and a hooked nose, which met her chin

2.3 Load and moment coefficients

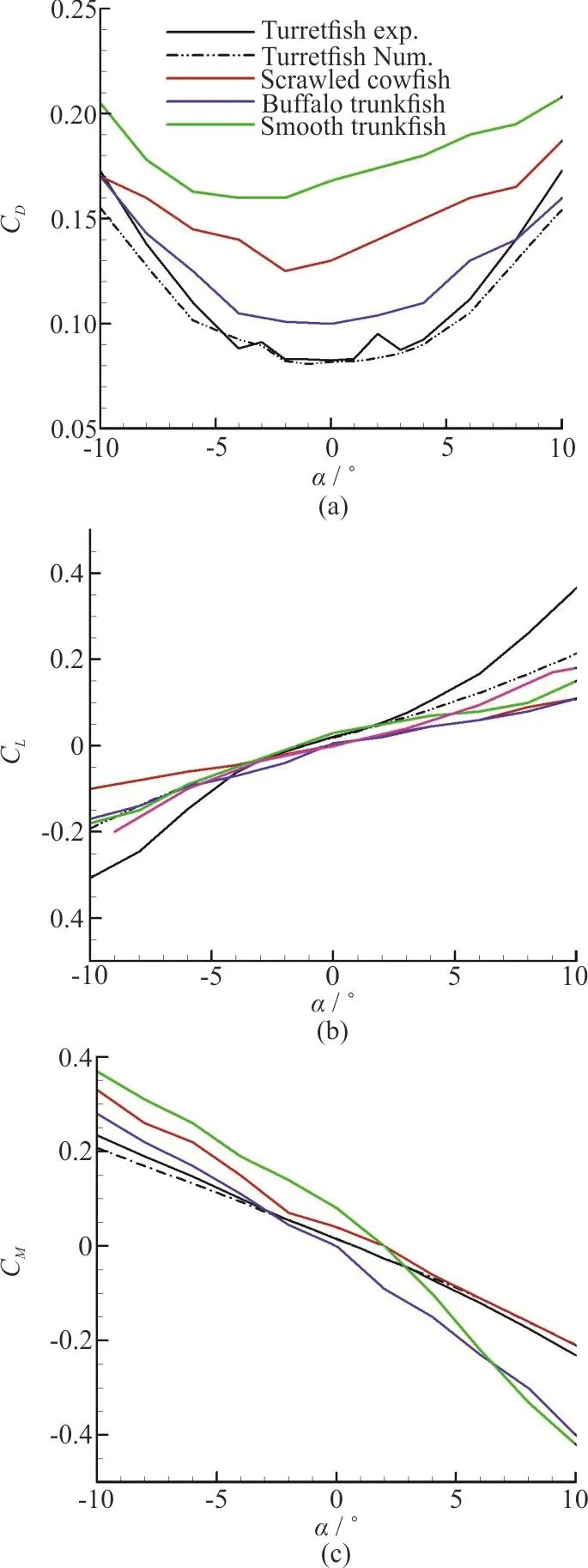

Fig. 14 (Color online) (a) Drag coefficients, (b) Lift coefficients,and (c) Pitching moment coefficients about center of mass, as functions of pitching angle of attack, for experimental and numerical approaches of current study, i.e.,on humpback turretfish, and comparison with results from Bartol et al.[6] for boxfishes with approximately similar shapes, Scrawled Cowfish, Buffalo Trunkfish and Smooth Trunkfish. In Lift coefficients section, a plot related to an adequate delta wing is presented too[6, 32]

Experimental and computational plots of Drag,Lift and Pitching Moment Coefficients are provided as functions of pi tching angl e of att ack in Fig. 14.Althoughtherearen’tanysimilarworkonthis specific species of boxfish, but results from Bartol et al.[6]for boxfishes with approximately similar shapes are included in Fig. 14 for comparison. Also lift coefficient plot for a delta wing is included in Fig.14(b)[6,32].

Force measurement results present an integrative view of the forces and pressures acting on the whole model. The results of maximum Reynolds number are presented here for both experimental and numerical approaches, due to the consistency between the results of different Re.

All of these boxfishes show similar trends to the humpback turretfish. In Fig. 14(a) the discrepancy for these four boxfishes is large around zero angle of attack and as it deviates from zero in either positive or negative directions the differences in drag coefficient for four boxfishes diminish. The humpback turretfish has a drag coefficient of 0.083 at 0° which is the lowest among all boxfishes. The buffalo trunkfish with approximately 0.1 drag coefficient has the closest value to that of humpback turretfish, while for smooth trunkfish, this value is more than twice of it at 0. As it is clear from the Fig. 14(a), the experimental and numerical approaches are in good agreement with each other.

Amongst all three plots in Fig. 14 the lift plots shows the largest discrepancy between experimental and numerical approaches and this difference could be mainly contributed by the accuracy limitations of our measuring instruments. The numerical approach of the current study and the three other studies on similar boxfishes have similar quantities, but the results of delta wing is very interesting, because it has the closest quantities to that of the humpback turretfish in most of the angles of attack. Delta wings use the same method as boxfishes to produce lift force, the lift is generated by vortex rings which form at the leading edge of the wing and grow posteriorly along and above the wing, thus called leading edge vortices(LEV).

In Fig. 14(c), it should be noticed that moment coefficient is the dimensionless form of the moment produced by the flow around the fish. This moment is a result of its body shape resisting deviations (pitching angle of attack) from its stable position. It’s necessary to state that being positive or negative is just based on the definition of the axis of pitching. As it is clear, the experimental and numerical approaches have good consistency, and scrawled cowfish shows the most similar behavior in restoring pitching moment among different species of boxfishes.

3. Conclusion and future works

In this work we hydrodynamically investigated the stability of humpback turretfish in pitching motions. A CAD model was extracted out of the point cloud of the real fish. A prototype was built from aluminum in CNC machine and experimentally tested in wind tunnel. Also the CAD model was computationally studied and tested in virtual wind tunnel.We applied a computational and two distinct experimental approaches, including force and pressure measurement. These approaches provide a great view and understanding of flow around the fish, visual results from computational study, i.e., vorticity and pressure contours, illustrate the generation and existence of spiral vortices originating from ventral and dorsal keels. These vortices are formed above the keels in positive pitch angles and under them in negative angles, making suction areas at the tail region of the fish that create returning forces to help the fish maintain its stable horizontal position. Pressure measurements are in agreement with vorticity and pressure contours and show pressure drop on the surface of the fish caused by the attached spiral vortices. Force measurements provide an overall view of all the forces and pressures acting on the carapace and their final resultants. It was shown that humpback turretfish has the smallest value of drag among fishes with similar shape. The similar behavior of turretfish with cowfish and trunkfishes, and more importantly the very close agreement between turretfish and delta wing was illustrated in the lift plots. The quantity of the restoring moment of turretfish, which was calculated and discussed about, was shown in the moment coefficient plot, having a very similar trend to that of cowfish.

After the experimental and computational studies on the Tetrosomus gibbosus, it can be understood that this species of boxfish can maintain its longitudinal stability. This is mainly because of its keels. The keels are the key point of production of the spiral vortices and play the main role in preserving the pitching movement stability of Tetrosomus gibbosus. The ventral keels are a little more effective in negative angles of attack. However it is shown that both ventral and dorsal keels play an important role in maintaining stability especially in positive angles of attack. They both produce big and effective column-like vortices,and by creating suction areas, help the fish to maintain its stability. The strengths of the spiral vortices varies with different angles of attack and grow stronger when the angle of attack further varies from zero, and are always stronger near the tail. These features together serve well to maintain the stability of the fish in pitching. In future studies, the role of carapace and keels in yawing stability will be studied, and effect and role of fins and tail may be studied too.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aref Vandadi, Hassan Nikpey, Mohammadreza DaqiqShirazi and Sina Meftah for their contribution to this research and their kindest helps and supports.

水動(dòng)力學(xué)研究與進(jìn)展 B輯2019年2期

水動(dòng)力學(xué)研究與進(jìn)展 B輯2019年2期

- 水動(dòng)力學(xué)研究與進(jìn)展 B輯的其它文章

- Effectiveness of radiative heat flux in MHD flow of Jeffrey-nanofluid subject to Brownian and thermophoresis diffusions *

- Three-dimensional flow field simulation of steady flow in the serrated diffusers and nozzles of valveless micro-pumps *

- Numerical study on variation characteristics of the unsteady bearing forces of a propeller with an external transverse excitation *

- Analysis of the flow characteristics of the high-pressure supercritical carbon dioxide jet *

- Pitch control strategy before the rated power for variable speed wind turbines at high altitudes *

- Study of flow characteristics within randomly distributed submerged rigid vegetation *