Analysis of the flow characteristics of the high-pressure supercritical carbon dioxide jet *

Man Huang , Yong Kang , Xiao-chuan Wang , Yi Hu , Can Cai

1. School of Power and Mechanical Engineering, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China

2. Hubei Key Laboratory of Water Jet Theory and New Technology, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China

Abstract: The supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) jet has a wide application prospect for rock breaking and jet fracturing in the development of the unconventional shale energy, due to its special physicochemical properties. To investigate its jet flow characteristics, the high-speed photography is used in experiments and the simulations through a compressible numerical model are carried out. It is shown that the jet flow field can be divided into three typical regions, the mixing layer possesses the same characteristics as a gas/gas turbulent mixing layer, with the divergent angles evidently smaller than those of the incompressible jets.The predicted results by the numerical model are in a good agreement with those of the experimentations. Through the dimensionless analysis, the potential core shows a length of about 9d and an increasing trend with the increase of the inlet pressure while the decay rate shows a decreasing trend, and the radial profiles consistent well with the “U e-η*” normalized method. In addition, a significant temperature drop of the SC-CO2 is observed between the nozzle inlet and the exit. A simple and convenient semi-empirical equation for calculating this temperature variation is deduced. Finally, the flow characteristics suggest that the SC-CO2 jet should be treated as a compressible jet.

Key words: Supercritical carbon dioxide jet, flow characteristics, experiment and simulation, unconventional shale energy

Introduction

With the progress of the oil and gas exploration and development all over the world, the unconventional shale energy becomes more and more important and is considered as the potential sustainable resource and the general strategic direction[1-2]. Compared with the traditional coal or oil, more consumption of natural gas could decrease the emissions of air pollution and greenhouse gasses. Unconventional shale energy is a very promising source of oil and gas[3]. It has attracted much interest and becomes a hotspot not only in industry but also in scientific research, because of its rich reserves and long production period. Efficient drilling and fracturing are important technologies in the unconventional shale energy exploitation, but the traditional water-based drilling and fracturing have several shortages, such as the damage to the water sensitive reservoir, the poor water resources in some areas, the water resource contamination and the over-extraction[4-5]. Moreover,chemicals in the water-based drilling and fracturing can cause the groundwater contamination in regions of increasing unconventional oil and gas development(UD). In more specific terms, it is reported that the UD activities can elevate the levels of various compounds, such as alcohols, chlorinated species, and BTEX compounds, in the groundwater in the Barnett and Marcellus shale regions[6-8]. Besides, it is concluded in Shrestha’s review that deterministic and probabilistic events related to the UD in the Bakken shale region can pose long-term risks to the groundwater[9]. The groundwater contamination in the shale energy development areas may adversely affect the health of local residents. As a result, attempts were made to develop new methods to replace the traditional technique. The SC-CO2has been regarded as a promising drilling and fracturing fluid for the development of the unconventional shale energy, due to its unique properties, and it attracts full attention and interest.

The SC-CO2is in a special state when the pressure is above 7.38 MPa and the temperature is above 304.13 K, with many unique physical properties as a drilling or fracturing fluid[10]. The advantages of the SC-CO2as a drilling or fracturing fluid can be summarized as follows[11-13]. The use of the SC-CO2as a drilling and fracturing fluid can reduce the hydration swelling of the clay in shale energy reservoirs, which is conducive to protecting the reservoir and enhancing the recovery. The SC-CO2jet has a higher rock breaking and fracturing capacity,favorable to reduce the exploitation cost of the shale energy and conducive to protecting the environment.The shale gas and condensate are in the gas phase in the formation, mainly in the free, dissolved and adsorption state in the reservoir. Owing to the strong adsorption of the SC-CO2to the shale matrix, the shale gas and condensate in the adsorbed state can be replaced by the SC-CO2, to enhance the recovery.Additionally, the SC-CO2can also provide a driving force for the flow of the shale gas and condensate in the free and dissolved state in the reservoir pores. The dissolution of the SC-CO2in the viscous shale oil may reduce the crude viscosity, improve the oil-water mobility ratio and extend the sweep area. What is more, when the SC-CO2dissolves into the crude oil,the volume of the crude oil is expanded, the flow energy is enhanced, the oil-water interfacial tension is significantly reduced and the residual oil saturation is decreased. Moreover, when the SC-CO2and the crude oil are mixed together, not only the light hydrocarbons in the crude oil can be vaporized and extracted but also a mixed zone of the SC-CO2and the light hydrocarbon may be formed. A solution-gas-drive effect is also provided. They are conducive to improving the flooding efficiency and enhancing the oil recovery. These properties provide a significant advantage of the SC-CO2jet as the assistive tool for drilling and fracturing, which partly offsets the deficiency of the traditional water-based drilling and fracturing fluid to meet the high demand of the increasingly important unconventional gas resource exploration and development.

Several experimental and numerical studies for the high pressure SC-CO2jet with great velocity and highly concentrated energy were reported. Compared to the conventional water jet, the high pressure SC-CO2jet possesses a stronger rock breaking capacity and a better pressure boost effect within the cavity. The test results show that the threshold rock breaking pressure for the granite using the SC-CO2jet is about 2/3 of that using the water je; for the shale,the threshold rock breaking pressure is less than 1/2 of that using the water jet. The numerical results indicate that the boost pressure of the SC-CO2jet fracturing is 2.4 MPa, higher than that of the water jet when the drop of the nozzle pressure is 30MPa[14-16]. Furthermore, in order to provide some fundamental data for the development of the SC-CO2jet assisted drilling technique, the wellbore dynamical flow characteristics are determined by a series of experiments and simulations for various nozzle diameters, standoff distances, jet pressures and jet lengths. The results indicate that the static pressure of the CO2decreases significantly during the jet impact process, the bottom-hole pressure and the temperature increase with the increasing nozzle diameter but decrease with the increasing standoff distance; the increase of the wellbore inlet pressure results in the increase of the bottom-hole pressure and the decrease of the temperature, and there is an optimum value for the jet length[17-18]. The impact performance and the flow field of the SC-CO2impinging jet are numerically investigated, and the comparison of the results with those of the water jet indicates that the SC-CO2impinging jet has a stronger impact pressure and a higher maximum velocity than the water impinging jet[19]. For the recent hot shale gas, experimental results show that, after the erosion by the SC-CO2jet,grid-like damages occur on the surface of the shale when a large volumetric layered failure forms in the whole sample, meanwhile, the microstructure of the shale is changed, which results in the strength reduction and the easy breaking of the rock, indicating that the SC-CO2jet possesses a good shale breaking effect[20-21].

The properties of the SC-CO2are sensitive to the thermodynamic conditions, which means that in experiments, it is necessary to consider the complex jet flow field and the high pressure and so far, the flow characteristics of the high pressure SC-CO2jet,including the structural characteristics, the velocity distributions and the nozzle temperature variations,are still not well understood. Hence, a jet visual test system combined with a high-speed photography camera is set up, meanwhile, a compressible numerical model is developed, in order to clarify the flow behavior of the SC-CO2jet and provide some fundamental data for engineering applications and further scientific researches.

1. Experimental setup

1.1 The jet visual system

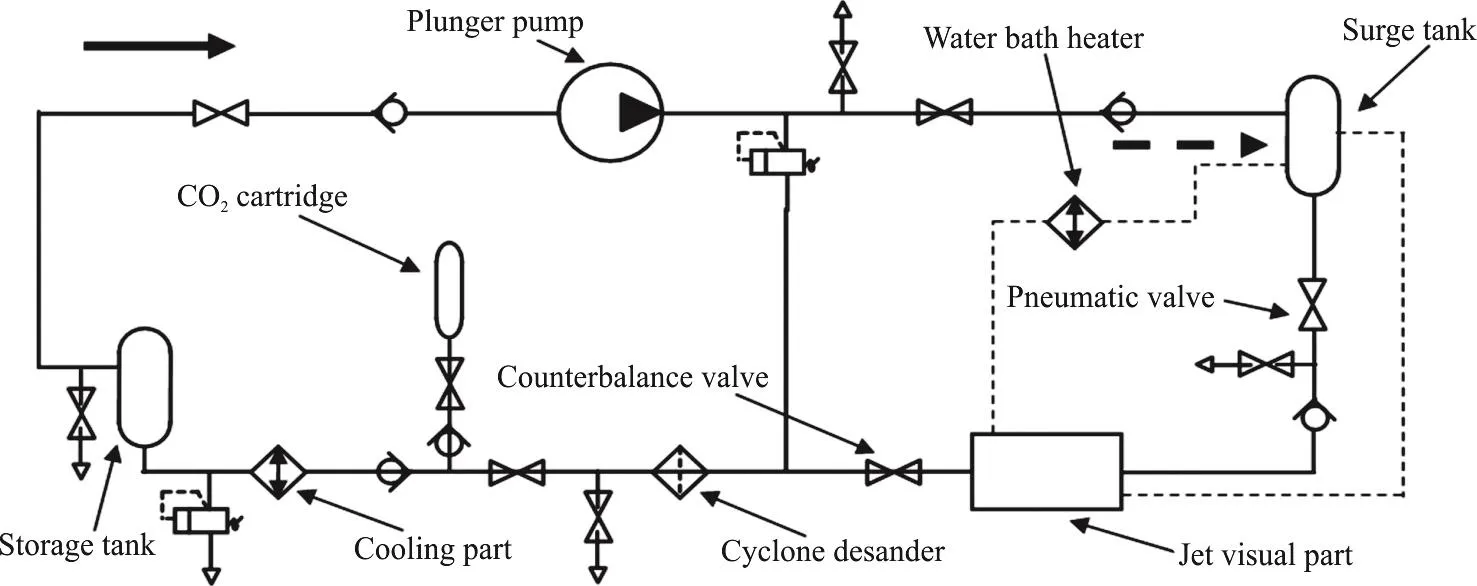

Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of the experimental setup

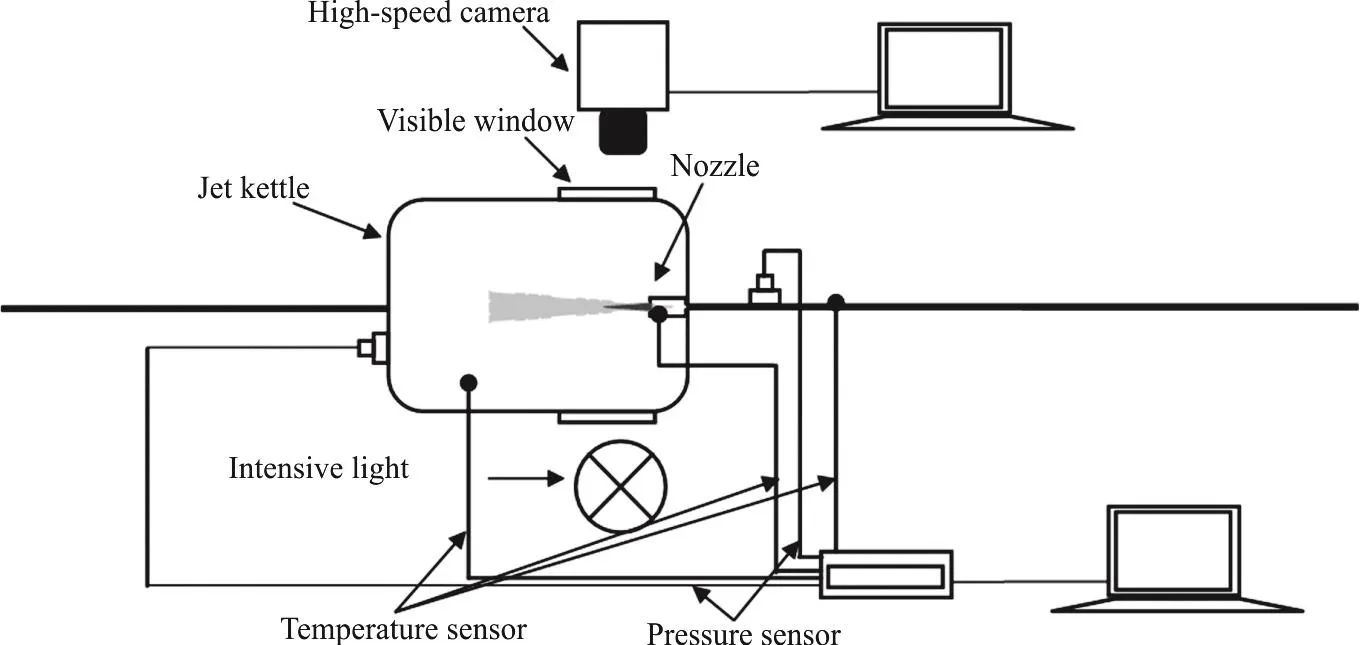

Fig. 2 Schematic diagram of the instrumentation system

The functional parts of the jet visual system for the formation of the SC-CO2jet are shown in Fig. 1.The thick solid arrow indicates the flow direction of the CO2, while the dotted one indicates that of the hot water. The gaseous CO2from the cartridges changes into the liquid CO2by the cooling effect of the cooling part and the latter is temporarily stored in the storage tank. Then, the liquid CO2is pressurized by the plunger pump and temporarily stored in the surge tank.The surge tank and the jet kettle are heated by the water bath heater. When the pressure and the temperature in the surge tank are both above the critical point, the CO2would come into the supercritical state.Then the SC-CO2jet could be created in the jet visual part by adjusting the pneumatic and counterbalance valves.

1.2 Instrumentation measurements details

The instrumentation system is shown in Fig. 2.Pressure measurements are taken at a sampling rate of 1kHz through BD/SENSORS DMP334 transducers with an accuracy of 0.175% in full scale. A pressure transducer is located in front of the nozzle inlet, to monitor the inlet pressure. The ambient pressure is measured by another transducer mounted in the jet kettle. The temperature measurements are made in the jet kettle, at the nozzle exit section and the places just upstream the nozzle inlet using type T thermocouples with an Omega thermocouple of a total accuracy of 1 K. The probe measuring the temperature at the nozzle exit is in a close proximity to the edge of the inner bore, but without sticking out, to minimize the interference with the jet flow.

Fig. 3 (Color online) Setup of the high-speed photography

The high-speed photography camera and the cold light source are positioned near the visual windows, as shown in Fig. 3. The high-speed camera is of a model of FASTCAM SA5, with the maximum resolution of 1 024 at the speed of 7 000 fps. The light source is a LED cold light illuminator. In the experiments, the exposure time is 1/7000 s for observing the instantaneous outline and the inside boundaries of the SC-CO2jet.

1.3 Experimental uncertainty

The primary experimental uncertainty includes the accuracy of the pressure transducers for the inlet and ambient pressures and the thermocouples for the fluid temperature, less than 0.175% and ±1 K, respectively. The method for measuring the divergent angle also adds some experimental uncertainty. In order to reduce this uncertainty, thirty images are randomly selected under each condition, with the angles measured and then averaged. The averaged divergent angles are employed in the following experimental analysis.

2. Numerical method

2.1 Governing equations

In view of the compressibility of the SC-CO2and the heat transfer in the jet flow field, the compressible RANS equations including the energy equation are used for governing the simulation.

The continuity equation

The momentum equation

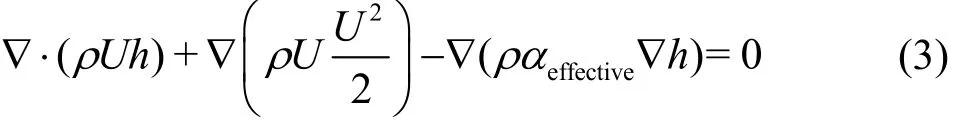

And the energy equation:

where

In Eqs. (1)-(6), ρ is the density of the fluid, U is the velocity (vector), p is the static pressure, h is the specific enthalpy, μ is the dynamic viscosity,tμ is the turbulence viscosity, Ptr is the turbulent Prandtl number, α is the thermal diffusivity,tα is the turbulence diffusivity, The subscript effective means the combination of the thermal and turbulence properties.

2.2 Turbulence model

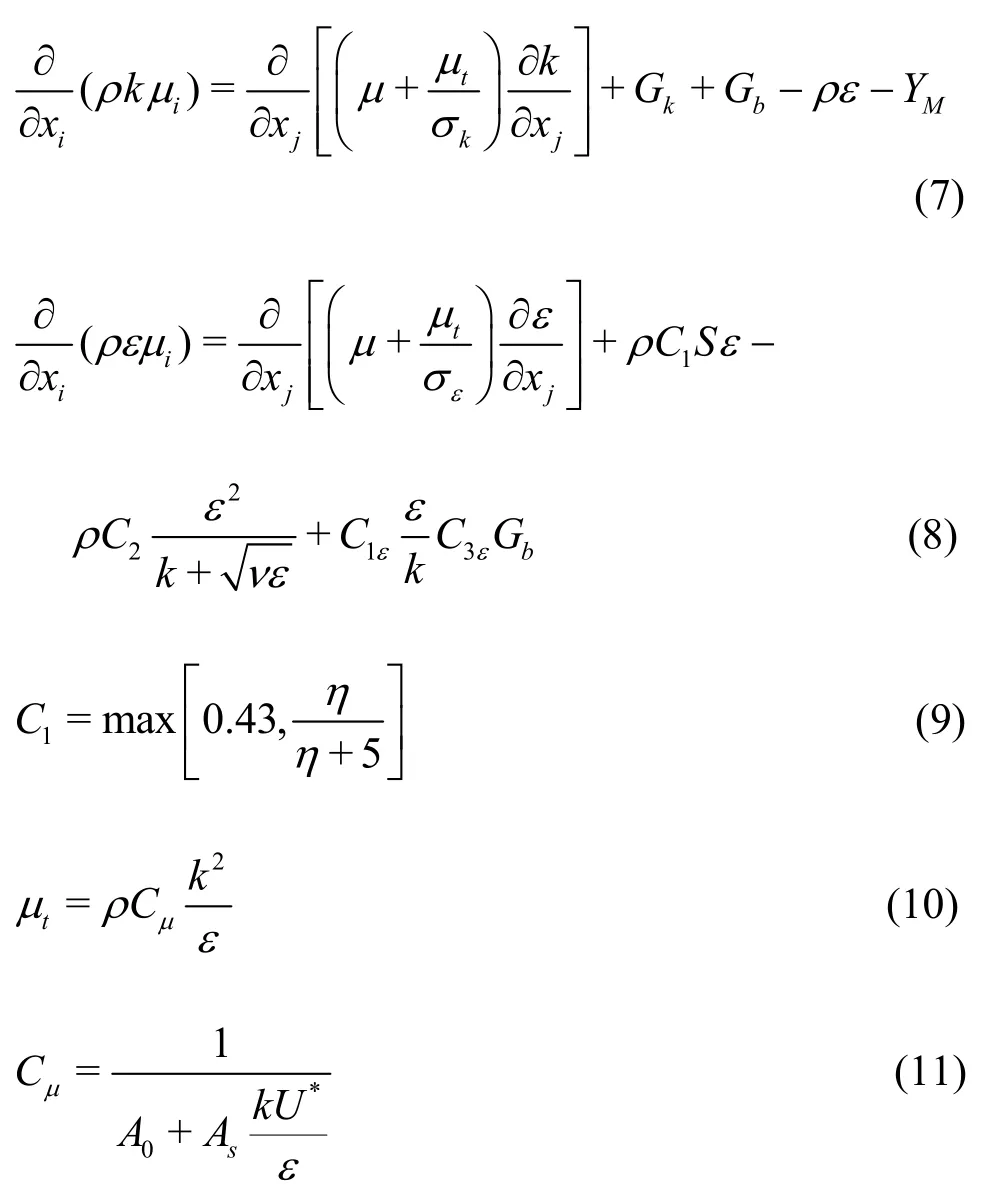

The performance of the realizable k-ε model for the prediction of a round jet has been found to be substantially better than that of the standard k-ε model, owing maybe to its certain mathematical constraints on the Reynolds stresses and the consistency with the physics of the turbulent flows by its two modifications. Therefore, the realizable k-ε model is adopted here. The equations are as follows:

where C1ε=1.44, C2=1.9, σk=1.0, σε=1.2.Cμis the difference between the realizable and RNG k-ε models, which is no longer constant and is computed from Eq. (11).

In Eqs. (7)-(11), Gkis the turbulent production,Gbis the generation of the turbulence. The dilatation dissipation due to the compressibility of the SC-CO2is modeled by YM.

2.3 Calculation of the physical properties

Since the properties of the SC-CO2vary with the variations of the pressure and the temperature, the calculation of the properties should be coupled with the flow equations during the iterative process in the simulations for the jet flow field. The properties are calculated using the very accurate formulas derived from the Helmholtz free energy given by Span and Wagner.

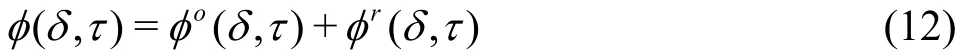

The fundamental equation based on the dimensionless Helmholtz energy is

The pressure is defined as

The specific isobaric heat capacity is described as

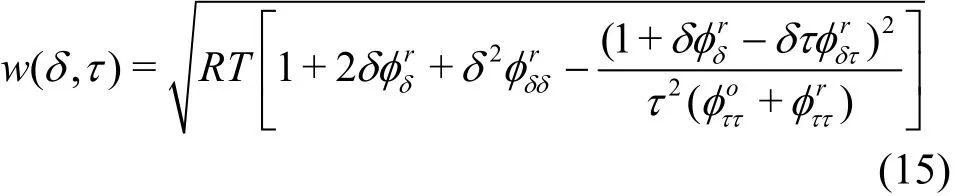

The speed of the sound is obtained from the relation

In Eqs. (12)-(15), φ is the total Helmholtz free energy,oφ is the part depending on the ideal gas behavior,rφ is the part obtained by taking into account the residual fluid behavior, δ = ρ/ ρcis the reduced density and τ = Tc/T is the inverse reduced temperature, both of which are made dimensionless by the critical values, ρc, Tc. R is the specific gas constant,,,,andare the first or second derivatives ofoφ,rφ with the respect to δ or τ.

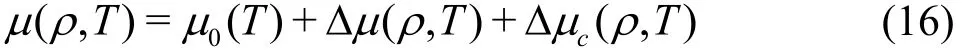

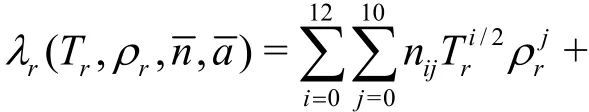

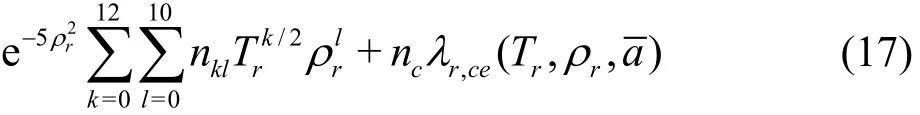

In addition, the viscosity and the thermal conductivity of the CO2are calculated by Eqs. (16), (17)[22],respectively, as follows

where μ0(T) is the viscosity in the zero-density limit,Δμ ( ρ,T) is an excess viscosity which represents the increase of the viscosity at an elevated density over the dilute gas value at the same temperature, and Δμc( ρ,T) is the critical enhancement accounting for the increase of the viscosity in the immediate vicinity of the critical point.

where j≠0 when i=0, and l≠0 when k=0.Tr, ρrare relative to their critical values, λris relative to Λc, a parameter derived from the dimensional analysis.

The calculation of the physical properties in the iterative of the flow field is as follows. In the first step,the physical properties of the SC-CO2in the flow field are calculated from the initial temperature and pressure fields. In the second step, the temperature and pressure fields are calculated using the physical properties obtained in the previous step. In the third step, the physical properties are updated with the temperature and pressure fields obtained in the previous step. The above steps are repeated until the calculation converges.

2.4 Boundary conditions and meshing

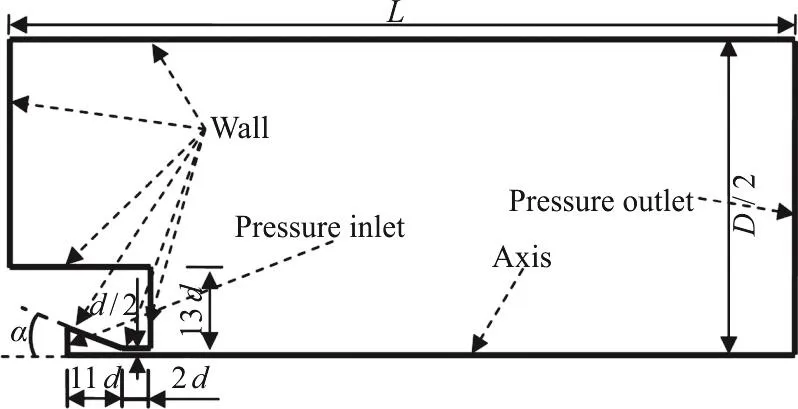

The computational geometry and the boundary conditions are shown in Fig. 4. Since the flow field is axisymmetric, a 2-D model is adopted to save the computational time. The computational domain consists of two parts, the region inside the convergence nozzle and the ambient region inside the jet kettle.The nozzle geometric parameters are as follows: the exit diameter of the nozzle is d=0.001m , the length of the cylindrical section is 2d, the length of the convergent section is 11d and the convergent angle is 2a=13.5°. For the jet kettle, the inner diameter is D =150d, and the length is L=230d.

Fig. 4 Computational domain

The numerical boundary conditions are set according to the experimentations. The inlet of the nozzle is defined as the pressure inlet, while the exit of the jet kettle is defined as the pressure outlet. The centerline of the flow field is set as the condition of an axis. The others are defined as the no-slip wall condition,meaning non-split and non-penetration for the velocity,and zero gradients for the pressure and the temperature.

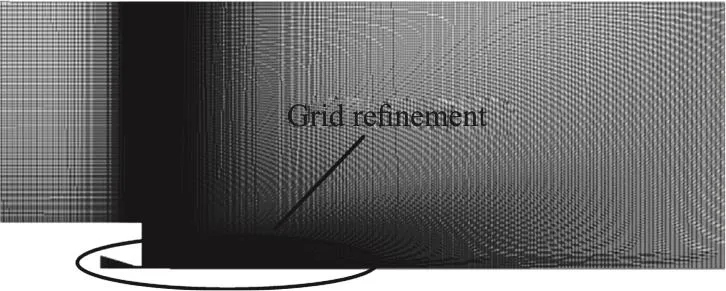

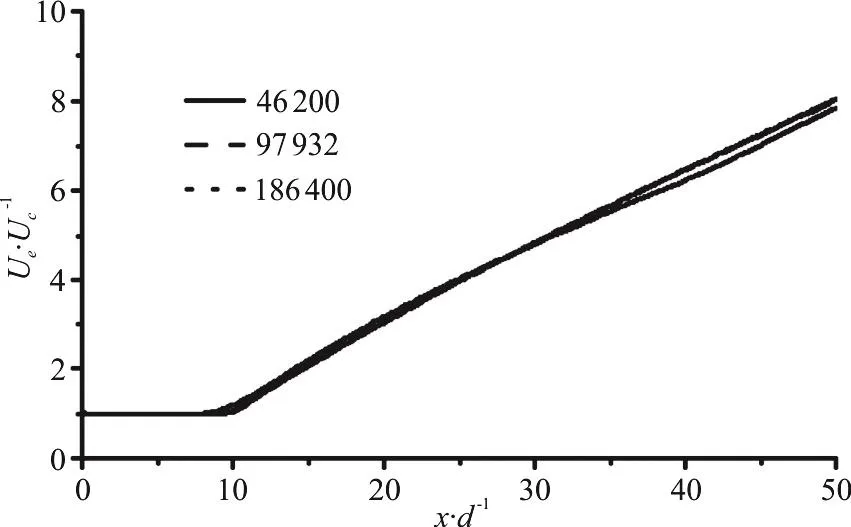

Figure 5 shows the mesh built up with the structured hexahedral cells. Considering the great variation in the gradients of the flowing parameters,the domains inside and near the nozzle are refined.The grid independency is tested through the centerline decay of the axial mean velocity on three different mesh densities, 46 200, 97 932 and 186 400 cells, as shown in Fig. 6, while the inlet pressure is 50 Mpa,the ambient pressure is 20Mpa and the fluid temperature is 350 K. From the curves, little difference is observed between the cases of 97 932, 186 400 cells,and a small deviation is observed in the case of 46 200 cells.To improve the computational efficiency, the mesh with 97 932 cells is adopted.

Fig. 5 Overview of the computational grid

Fig. 6 U e /Uc for different grid resolutions

2.5 Numerical strategy

The finite volume method is used to discrete the governing equations and the QUICK scheme is used for the spatial discretization. The “pressure based implicit” solver is employed in the simulations, and the SIMPLE algorithm is applied for the coupling of the pressure and the velocity.

3. Results and discussions

3.1 Jet visual structure

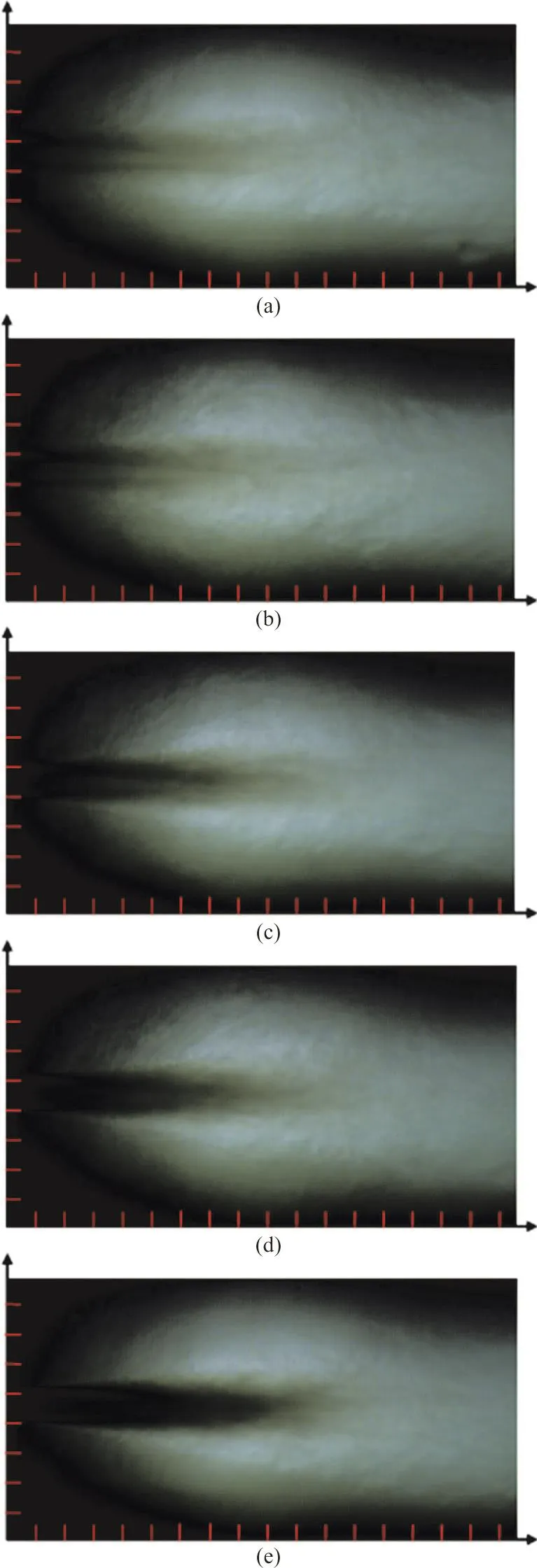

Fig. 7 (Color online) Back-illuminated images of the SC-CO2 jet at fixed supercr itical tem perature of, Ti n= Ta =350 K ,and supercriticalambientpressure, pa / pc =2.71, but with varying inlet pressures

Figure 7 shows the images of a SC-CO2jet at a fixed supercritical jet kettle pressure (pa/ pc=2.71)and a temperature (350K) but at various nozzle inlet pressures. From A to E, theinl et p ressur e increases:pin/ pc=4.07,5.42,6.78,8.13and9.49,and Pcis the critical pressure equal to 7.38 MPa. The subscript“in ” indicates the nozzle inlet parameter, “e”indicates the nozzle exit parameter, “a” indicates the ambient parameter, “c” indicates the critical para-meter, and “r” indicates the ratio. The nozzle exit is located just at the vertical axis. Both the horizontal and vertical axes are scaled with the nozzle diameter,obtained proportionally from the image.

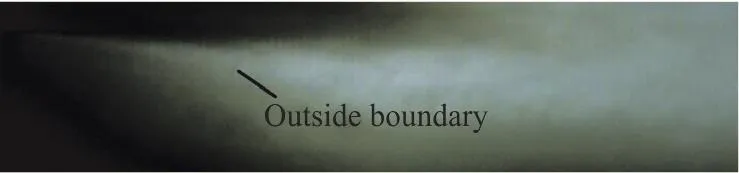

The flow field in the images could fall into several regions, on the basis of the demarcations where the index of refraction changes, due to the variations of the fluid density. The flow field images with different nozzle inlet pressures show similar structural characteristics. A light conical region starts from the nozzle exit could be recognized, as surrounded by a distinct inside boundary. The transparency in this region changes little in the dynamic flow field videos obtained from the high-speed camera.This indicates that the density of the fluid is almost constant. Another region around the light conical region is much darker in color than the conical region.It becomes shallower gradually from inside to outside,with no obvious outer boundary. The density of the fluid in it is transformed from that in the light conical region to that in the ambient region, with changes of the index of refraction and a poor translucency. The fluid in this dark region shows a great unsteady in the flow field videos. Another demarcation is the interface of the jet and the ambient fluid, which could be clearly observed in the dynamic flow field video. In the region between these demarcations and the dark region, the fluid is seemingly expanded into the same state as the ambient fluid since almost no transparency change can be observed. This flow structure is mainly generated by the density difference and the entrainment between the jet flow and the ambient fluid.

Figure 8 shows selected images from Fig. 7 with an additional magnification to represent the details of the mixing layer regimes. Both of the inlet pressure and the ambient pressure are in the supercritical state,the jet behavior is very different from the description given by the classical liquid breakup theory. The droplets and the coherent comb-like dense structures do not appear near the mixing layer, nor does the simple atomization regime. The mixing layer in Fig. 8 corresponds roughly to a classical single phase gas/gas turbulent mixing layer, similar to that of the gas/supercritical N2jet. This may be due to the gas like properties of the SC-CO2.

Fig. 8 (Color online) Images of the jet at its outer boundary,pi n/ p c =9.49, p a / p c =2.71, Ti n= Ta=350 K

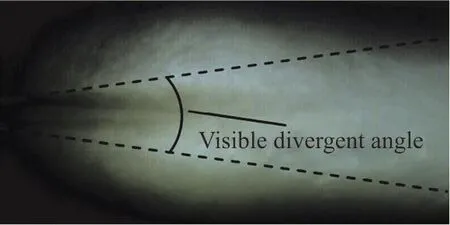

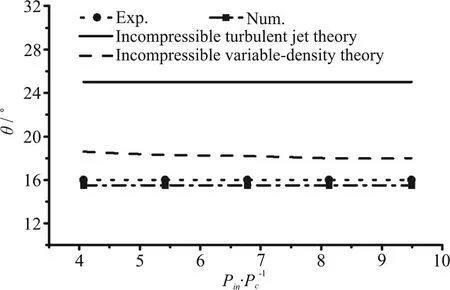

The visual divergent angle, θ, is commonly used for the assessment of the characteristics of the spreading process of jets and mixing layers. Figure 9 shows the visual divergent angle of the SC-CO2jet.The visual angle is determined by the outermost observable extent, namely, the interface (dashed line)of the jet flow and the ambient fluid of the jet. This initial visual divergent angle is measured using the Auto CAD software. The images are proportionally enlarged in the software. Then, the lines started from the nozzle exit edge are drawn to describe the averaged outer boundary of the jet. The included angle of the two boundary lines is then measured by the angle measurement tool. Thirty images are randomly selected under each condition, to measure the angles and then the results are averaged. The divergent angles are also extracted from the results of the numerical simulations for a comparison.

Fig. 9 (Color online) The schematic diagram of the visual divergent angle

Fig. 10 The visual angles for different types of jet

Figure 10 shows the divergent angles of the SC-CO2jet obtained from formula calculations, experiments, and numerical simulations. The incompressible turbulent jet theory is based on the Prandtl’s mixing length theory, in which the effect of variabledensity and compressibility are not incorporated. It is apparent that this simple theory significantly over-predicts the divergent angles of the SC-CO2jet.On the account of the entrainment phenomenon and a geometric argument, an incompressible variabledensity theory is derived, which is valid for the prediction of the spreading characteristics of an incompressible variable-density theory. The divergent angles calculated from this theory are also larger thanthose of the presented experimentations and simulations. The smaller divergent angles of the SC-CO2jet may be caused by the compressibility of the fluid,since it is well-known that the compressibility can reduce the turbulent mixing efficiency, resulting in a smaller divergent angle. The compressible numerical model coupled from the above equations gives a good prediction of the divergent angle. This might be because the density variation and compressibility of the SC-CO2are both considered in the iterative process through the Span-Wagner state equations and the compressible Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equations.

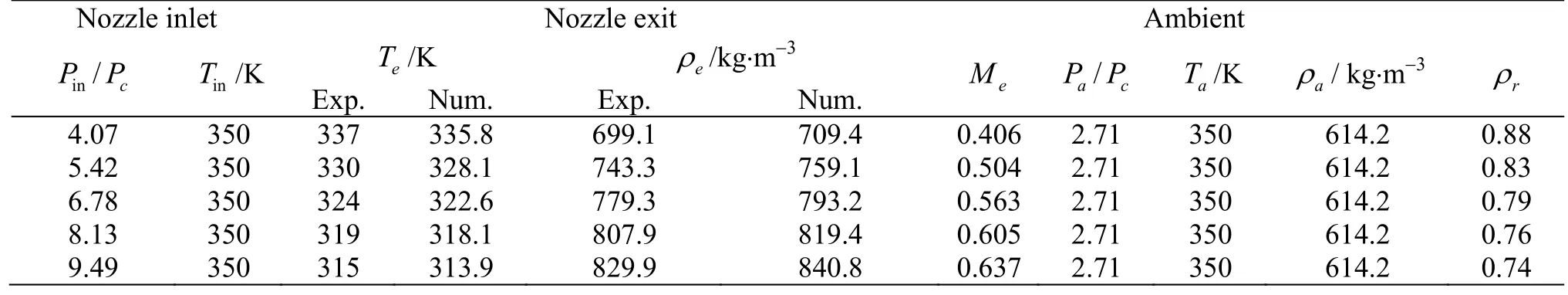

Table 1 The data of thermodynamic parameters of the jet and ambient fluid

Table 1 gives the conditions of the nozzle inlet,the nozzle exit and the ambient fluid of the SC-CO2jet in the experimentations and simulations. The values of the thermodynamic parameters at the nozzle inlet and the ambient fluid are given conditions, while the data of the nozzle exit are measured during the experiments and extracted from the results of the simulations. With the measured temperature (Te)and ambient pressure, the nozzle exit density is calculated through the Span-Wagner state equation.Notice that the SC-CO2jet has a density ratio (ρr),with the jet Mach numbers (Ma) greater than 0.3, as the critical value for the consideration of the compressibility of the flow in the previous comparison analysis for the divergent angle, therefore, the SC-CO2jet should be treated as a compressible jet. Comparing the measured values and the calculated values at the nozzle exit, it is found that the compressible numerical model can well predict these parameters of the SC-CO2jet. Furthermore, the divergent angles extracted from the simulations are very close to those of the experimentations. It may be concluded that the compressible numerical model has the capacity to capture the characteristics of the jet flow field of the SC-CO2.

3.2 Jet velocity distribution

3.2.1 The centerline mean axial velocity decay

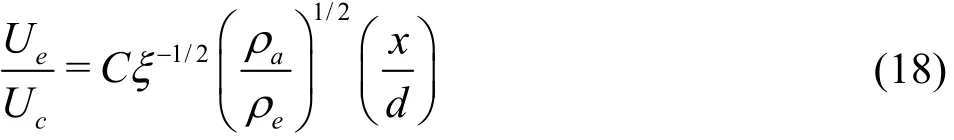

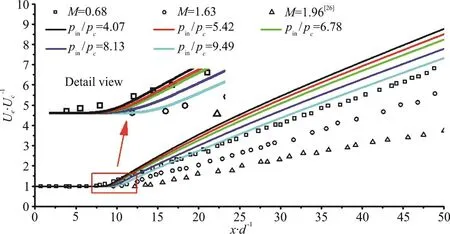

The decay of the mean centerline velocity as a function of the distance from the nozzle is shown in Fig. 11. The inverse of the mean centerline velocity is normalized by the inverse of the nozzle exit velocity,while the distance from the nozzle is normalized by the nozzle exit diameter. Over the potential core region, the centerline velocity of the SC-CO2jet is decayed at a constant rate. The length of the potential core of the SC-CO2jet is about 9d, nearly twice of that of the incompressible jet and close to that of the compressible jet. A small increasing trend of the potential core could be observed at the turning segments of the curves. The decay rates of the SC-CO2jet are close to those of the subsonic compressible air jet (M a =0.68), and larger than those of the supersonic compressible air jet with high Mach numbers.The decay rate sees a decreasing trend with the increase of the inlet pressure, namely the increasing nozzle exit Mach number. One possible reason for the variation characteristics of the potential core and the decay rate of the SC-CO2jet is the compressibility.Reducing the turbulent mixing effect of the compressibility is commonly considered to result in an increasingly longer potential core and a decreasingly lower decay rate with the increase of the nozzle exit Mach number. Not only the compressibility but also the nozzle exit condition has an influence on the variation of the mean centerline velocity. On the basis of the dimensional analysis, this influence can be clarified with the following theoretical equations

where C is a constant, ξ is the “force coefficient”,equal to 1 for the presented SC-CO2jet.

The virtual origin is defined as the point where the upstream elongated line of the decay curve intersects with the line of Ue/Uc=1. The parameter xcis the distance from the virtual origin to the nozzle exit, which is an efficient measurement of the potential core length, though a little larger. From Eq.(18), xccan be written as follows

Fig. 11 (Color online) Centerline decay of axial mean velocity

Fig. 12 (Color online) Radial profiles of axial mean velocity

where D=1/C.

With Eqs. (18), (19), it is easy to see that the decrease of the density ratio, namely the increase of the inlet pressure, also results in a decrease of the mean centerline velocity decay rate and an increase of the potential core length of the SC-CO2jet, as consistent with the aforementioned effect of compressibility.

3.2.2 The radial distributions of the mean axial velocity

Figure 12 shows the radial distributions of the axial mean velocity for the SC-CO2jet at five streamwise positions under the same inlet pressure of 30MPa, and under different inlet pressures just at the same position x/ d=4. The curves for the compressible air jet are also plotted in the figure for a comparison. The velocity is normalized by the nozzle exitvelocity Ueandisthedimensionless parameter for the radial position, where r0.5refers to the position where the mean velocity is 0.5Ue.This method of normalization is shown to be the most productive approach to deal with the mean velocity data for a compressible air jet. The radial profiles of the axial mean velocity at different streamwise positions under the same inlet pressure show a tendency to merge together. Only the region between η*=0-- 0.05 in the streamwise positions beyond the deviations still could be observed. In the region η*<0, the curve for the inlet pressure 70 MPa (blue potential core sees a small deviation, maybe due to the effect of the non-uniformity in the temperature distribution, which could change the velocity distribution in the jet flow field. At the same streamwise position x/ d=4, the radial distribution curves of the axial mean velocity under different inlet pressures are very close to each other, but slight dashed line) is higher than that forthe inlet pressure 30 Mpa (red solid line) and would intersect earlier with the line U/ Ue=1, while in the region η*>0,the curve for the inlet pressure 70 MPa is lower than that for the inlet pressure 30 MPa and would intersect earlier with the line U/ Ue=0. Curves for the inlet pressures 40 MPa, 50 MPa and 60 MPa are located between these two extreme positions. Since the radial extent is an expression of the relative spreading rate of the shear layer, it is indicated that the higher the inlet pressure (the higher nozzle exit Mach number), the lower the spreading rate will be. This trend is very weak compared with the referenced curves (dot-dash line) with a great difference about the exit Mach number, maybe because of the small difference of the SC-CO2jet exit Mach number, as shown in Table 1.The aforementioned reducing mixing efficiency effect of compressibility may be responsible for this weak trend between the SC-CO2jets.

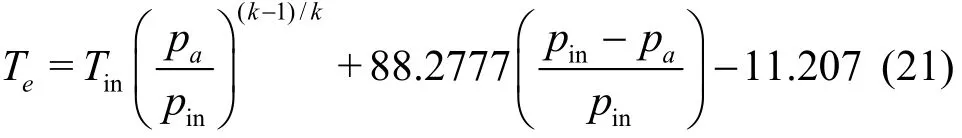

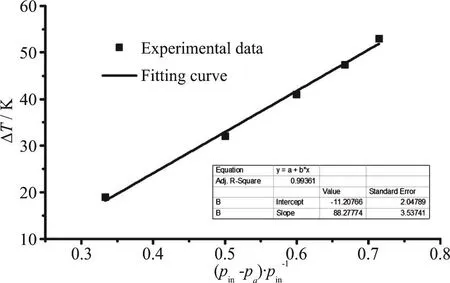

3.3 Jet temperature drop

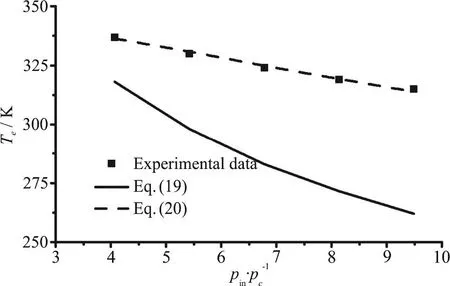

From Table 1, it could be noticed that there is an obvious temperature drop of the SC-CO2from the nozzle inlet to the exit. With the compressibility of the SC-CO2, the Joule-Thomson effect will be seen during the nozzle depressurization process. The measured temperature is a little higher than that from the simulations, maybe due to the inevitable heat exchange between the SC-CO2and the internal surface of the nozzle though the contact time is very short because of the high velocity, as not considered in the numerical simulation. There is a simple equation to calculate the temperature variation based on the adiabatic equation and the ideal gas state equation, as follows

where k is the adiabatic exponent, equal to 1.3 for CO2.

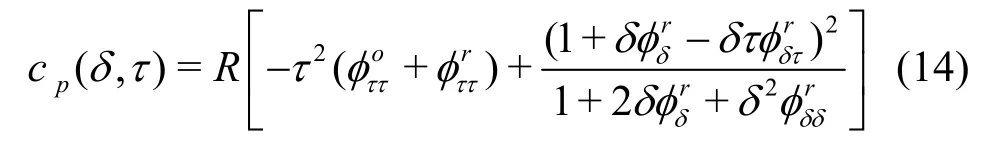

This equation significantly over-predicts the temperature drop for the SC-CO2jet, maybe due to the application of the ideal gas state equation in the equation. Since it is very difficult to build a simple and convenient equation by using the accurate and complex state equation of CO2, a semi-empirical equation for the calculation of the temperature drop is developed based on the experimental data. As shown in Fig. 13, the difference ΔT between the measured temperature and the calculated value from Eq. (20),could be linearly fitted very well with the dimensionless parameter (Pin-Pa)/Pin,where the adjust R -square and standard error for the linear fitting is also shown in Fig. 13. Adding this part to Eq. (20),then a semi-empirical equation with a good agreement with the experimental data (see Fig. 14), is obtained as

Fig. 13 Linear fitting of ΔT

Fig. 14 Comparison of the temperature predictions between Eqs.(20), (21)

4. Conclusions

(1) According to the variation of the transparency caused by the changing density in the flow field images obtained from the high-speed camera, three typical regions could be recognized in the jet flow field for the SC-CO2, the steady light conical region,the dark region, and the region in which the fluid appears to be the same with that of the ambient fluid.

(2) The mixing layer of the SC-CO2jet corresponds roughly to a gas/gas turbulent mixing layer,since the outer boundary of the jet shows the classical single phase gas-jet-like appearance. The divergent angle of the SC-CO2jet is about 16°, evidently smaller than that of the incompressible jets due to the compressibility and the density variation.

(3) The compressible numerical model has the capacity to capture the characteristics of the jet flow field of the SC-CO2, since the calculated values at the nozzle exit and the divergent angles extracted from the simulations are very close to those of the experimentations.

(4) The potential core of the SC-CO2jet has a length of about 9d and a small increasing trend with the increase of the inlet pressure, while the decay rate has a decreasing trend with the increase of the inlet pressure. The radial distributions of the axial mean velocity agree well as a whole with those obtained by the “Ue-η*” normalized method, with only a small deviation in part due to the non-uniform temperature distribution and compressibility.

(5) There is an obvious temperature drop of the SC-CO2from the nozzle inlet to the exit caused by the Joule-Thomson effect. A semi-empirical equation is derived, with a good prediction for the temperature variation through the nozzle of the SC-CO2jet.

(6) All difference about the divergent angles between the SC-CO2jet and the incompressible jets,the velocity distributions affected by the compressibility and the density variation, and the nozzle temperature drop due to the Joule-Thomson effect,suggest that the jet should be treated as a compressible jet.

- 水動力學(xué)研究與進(jìn)展 B輯的其它文章

- Effectiveness of radiative heat flux in MHD flow of Jeffrey-nanofluid subject to Brownian and thermophoresis diffusions *

- Three-dimensional flow field simulation of steady flow in the serrated diffusers and nozzles of valveless micro-pumps *

- Numerical study on variation characteristics of the unsteady bearing forces of a propeller with an external transverse excitation *

- Pitch control strategy before the rated power for variable speed wind turbines at high altitudes *

- Investigation of the stability and hydrodynamics of Tetrosomus gibbosus carapace in different pitch angles *

- Study of flow characteristics within randomly distributed submerged rigid vegetation *