Essen score in the prediction of cerebrovascular events compared with cardiovascular events after ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a nationwide registry analysis

Long LI, Ze-Ning JIN, Yue-Song PAN, Jing JING, Xia MENG, Yong JIANG,Hao LI, Cai-Xia GUO, Yong-Jun WANG,?, on behalf of the Third China National Stroke Registry investigators

1. Department of Cardiology, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China; 2. Department of Cardiology and Beijing Key Laboratory of Hypertension, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing,China; 3. Department of Neurology, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China; 4. China National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases, Beijing, China; 5. Department of Cardiology, Beijing Tongren Hospital,Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND The Essen risk score improves stratification of patients with acute ischemic stroke by early stroke recurrence.Recent study showed it could also predict myocardial infarction (MI). This study aimed to compare the Essen score’s ability to predict cerebrovascular events with compared cardiovascular events. METHODS We included patients with acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack within seven days from the Third China National Stroke Registry. One-year cumulative event rates of combined vascular events (a composite of MI, stroke recurrence or vascular death) and cardiac events (a composite of MI, heart failure or cardiac death) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The predictive value of the Essen score was assessed with C-statistics. In multivariate Cox regression analyses, we assessed whether Essen score, etiological subtype and imaging parameters were associated with outcomes. RESULTS Of 13,012 patients were included, the cumulative one-year event rates were 10.03% for combined vascular events and 0.77% for cardiac events, respectively. Compared with those with an Essen score < 3, patients with an Essen score ≥ 3 were more likely to have a subsequent combined vascular event [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.24?1.55]and cardiac events (HR =2.30, 95% CI: 1.53?3.44). The score tended to be more predictive of the risk of MI (C-statistic = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.55?0.71) and cardiac events (C-statistic = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.56?0.67) than stroke recurrence (C-statistic = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.54?0.57) and combined vascular events (C-statistic = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.54?0.57). In multivariable analysis after adjusted Essen score, patients with multiple acute infarctions or single acute infarctions and large artery atherosclerosis subtype were independently associated with an increased risk of combined vascular events. While the cardioembolism subtype was associated with an increased risk of cardiac events. CONCLUSIONS The Essen score is potentially more suitable for risk stratification of cardiovascular events than cerebrovascular events. Moreover, future predictive tools should take brain imaging findings and cause of stroke into consideration.

Stroke is the leading cause of mortality and disability worldwide.[1]Recurrent stroke and subsequent cardiac events are major contributors to mortality and disability after ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).[2]The identification of patients at high risk of cerebrovascular events or cardiovascular events is critically important for both in-hospital management and long-term secondary prevention.

There are many clinical scoring systems that can be used to predict the risk of stroke.[3]Among them,the Essen risk score is a simple clinical score that was derived to predict recurrent stroke based on the presence of prior vascular comorbidities and is one of the most established scores for patients with stroke.[4]It has been reported that the Essen score could also identify patient subsets who may be at sufficiently high risk of myocardial infarction (MI) among patients with TIA or ischaemic stroke without prior coronary artery disease (CAD), and the score tended to be more predictive for the risk of MI than that of recurrent ischaemic stroke.[5]However, the Essen score has not been validated for cardiac events compared to recurrent cerebrovascular events.

Growing evidence has shown that both clinical scores and brain imaging are associated with recurrent stroke in patients with TIA/minor stroke[3,6]and ischaemic stroke.[3,7]Moreover, clinical scoring predictive tools have limited discrimination ability due to their poor performance.[6,8,9]Vessel imaging and neuroimaging are determinant factors for predicting recurrent stroke.[7,10,11]It is uncertain whether imaging findings and the aetiological subtype of stroke could improve risk stratification beyond the Essen score. The Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR-III) is a nationwide clinical registry of ischaemic stroke or TIA in China that was designed to establish Chinese ischaemic cerebrovascular disease aetiology classification and to build new risk prediction models or scoring systems.[12]Here, this study aimed to compare the Essen score’s ability to predict cerebrovascular events with cardiovascular events after ischaemic stroke or TIA. In addition,we determined whether imaging findings and cause of stroke could improve the predictive value based on the Essen score.

METHODS

Study Population

Data were derived from the CNSR-III, and the design, rationale and baseline information of CNSR-III have been described previously.[12]In brief, the CNSRIII was a nationwide prospective hospital-based cohort study that enrolled consecutive patients aged ≥18 years admitted to 201 hospitals from 22 provinces and four municipalities who had an ischaemic stroke or TIA within seven days of the onset of symptoms between August 2015 and March 2018. The diagnosis of acute ischaemic stroke was confirmed by brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography according to the World Health Organization criteria.[13]The probable cause of ischaemic stroke or TIA was further classified according to TOAST (Trial of Org 10712 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification: large artery atherosclerosis(LAA), cardioembolism (CE), small-vessel occlusion,other determined cause and undetermined cause.[14]Data are available upon reasonable request after the Academic Committee of CNSR-III approved the plan.

Patient data, including patient demographics, medical history, previous medication, laboratory tests,risk factor assessment and acute phase management information, were collected by trained research coordinators through face-to-face interviews with patients at each site. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital (KY 2015-001-01). All patients provided written informed consent according to national guidelines.

Imaging Data Collection

Brain imaging was performed at baseline following standard protocols for every patient. Brain imaging included brain MRI [T1 weighted, T2 weighted,fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) with apparent diffusion coefficient maps and magnetic resonance angiography]or computed tomography (if a patient was contraindicated to MRI), at least one vascular assessment for intracranial arteries and at least one vascular assessment for extracranial arteries. Image data were collected in digital format on a disc and analyzed by the image research centre in Beijing Tiantan Hospital.Details were previously described.[12]

Acute infarctions (positive DWI) were diagnosed as hyperintense lesions on DWI images and further classified as multiple acute infarction (MAI) or single acute infarction (SAI) according to the infarction number. Uninterrupted lesions visible in contiguous territories were considered SAIs, and more than one lesion topographically distinct was defined as MAIs, according to previous DWI studies.[6,15,16]All brain imaging was read centrally by two experienced assessors with more than five years of experience practising clinical neuroscience who were blinded to each other and the study. Disagreements were further reviewed by a third expert and resolved by consensus.[16,17]

Follow-up and Outcomes Assessment

Patients were followed up at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after discharge and every year thereafter for five years. In this study, we only report oneyear outcomes. Patients were evaluated at followup for clinical events, compliance with recommended secondary prevention medication and risk factor control. Information was collected at each follow-up,including cardiovascular events and cerebrovascular events, all causes of death and medications use.Vascular events were confirmed from the treating hospital and judged by an independent Endpoint Judgment Committee. Death was either confirmed on a death certificate from the attended hospital or the local citizen registry.[12,17]

Combined vascular events were defined as a composite of MI, recurrent stroke (either ischaemic or haemorrhagic) and vascular death, whichever occurred first. Cardiac events were defined as a composite of MI, heart failure (HF) and cardiac death, whichever occurred first. Vascular death was defined as ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, sudden cardiac death, acute MI, death directly caused by HF and other cardiovascular death, including cardiac arrhythmias unrelated to sudden cardiac death, pulmonary embolism, cardiovascular intervention (unrelated to acute MI), aortic aneurysm rupture or peripheral arterial disease. Cardiac death was defined as sudden cardiac death, acute MI and death directly caused by HF.[12]

The Essen Risk Score

The Essen score was calculated according to a previous report.[4]The Essen score contains eight items(supplemental material, Table 1S): age, history of hypertension, history of diabetes mellitus, history of MI, other cardiovascular disease except for MI and atrial fibrillation, history of peripheral arterial disease, ever smoking and previous ischaemic stroke or TIA. The Essen score ranges from 0 to 9. One point is given for patients aged 65?75 years, 2 points for patients aged > 75 years and 1 point for the remaining items. The Essen score was used to categorize patients into a low-risk group (< 3 points) and a highrisk group (≥ 3 points).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are represented as mean ±SD or median [interquartile range (IQR)]. Categorical variables are represented as counts (percentages).The cumulative one-year event rate was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The discriminative ability of the predictive value of the Essen score was assessed with C-statistics and 95% confidence interval (CI). Calibration was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Given that the Essen score, acute infarctions on brain imaging, and TOAST classification have been previously reported to be associated with recurrent stroke,[3,6,7]a Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to evaluate whether these three predictors were independently associated with combined vascular events. Candidate variables withPvalue < 0.1 were divided into categorical variables and further included in the multivariable model. Additionally, we determined the predictive value of adding the LAA (TOAST) subtype as a binary variable and acute infarctions as a binary variable to the Essen score for the risk of combined vascular events.Here, 1 point was given for LAA subtype and 0 points for any other subtypes than large artery disease. In addition, 1 point was given for any acute infarctions and 0 points for no acute infarctions. Statistical tests were two-sided, andP-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary,NC, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

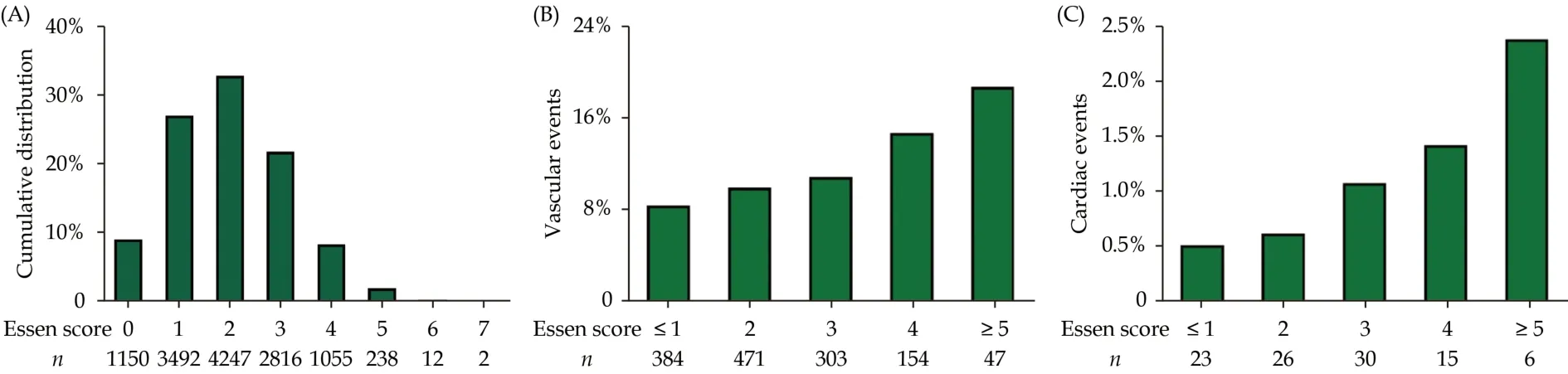

Among the 15,166 patients enrolled in the CNSR-III,2154 patients (16.6%) without available DWI imaging were excluded from the current analysis (supplemental material, Figure 1S). Of the 13,012 patients included in the imaging substudy, the mean age was 62.3 ± 11.2 years, and 68.3% of patients were men (Table 1). The average time from symptom onset to evaluation was 2 (IQR: 1-4) days. The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)score was 3 (IQR: 1-6), and the modified Rankin Scale score was 2 (IQR: 1-3). Most patents were adjudicated as ischaemic stroke (93.6%) in the final diagnosis, and the remaining patients were adjudicated as TIA (6.4%) with a median ABCD2 score of 4 (IQR:3-5). The LAA subtype according to TOAST classification was present in 3431 patients (26.4%), CE in 768 patients (5.9%) and small vessel occlusion in 2968 patients (22.8%). Among 11,423 patients (87.8%) with acute infarction(s) at baseline, 5903 patients had SAI, and 5520 patients had MAI. The cumulative distribution of Essen scores is shown in Figure 1A. The median Essen score was 2 (IQR: 1-3).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of study population.

Essen Score in the Prediction of Vascular Outcomes

A total of 12,709 patients (97.7%) completed at least one year of follow-up. At one year, 1305 combined vascular events (1240 recurrent stroke, 45 MI or 166 deaths from vascular causes) and 100 composite cardiac events (45 MI, 26 HF or 44 deaths from cardiac causes) had occurred. The one-year rates of combined vascular events, recurrent stroke, MI and composite cardiac events were 10.03%, 9.53%, 0.35%and 0.77%, respectively.

The one-year rate of combined vascular events increased for patients from lower to higher Essen score categories, ranging from 8.27% in those with an Essen score ≤ 1 to 18.65% in those with an Essen score ≥5 (Figure 1B and supplemental material, Table 2S).An Essen score of 3, which is often regarded as the cut-off point of the low-risk group and high-risk group, identified a subgroup at a risk of vascular events (10.76%) similar to that of the total population(10.03%). Similar results were obtained by analysing the association between the Essen score and cardiac events (Figure 1C and supplemental material,Table 2S).

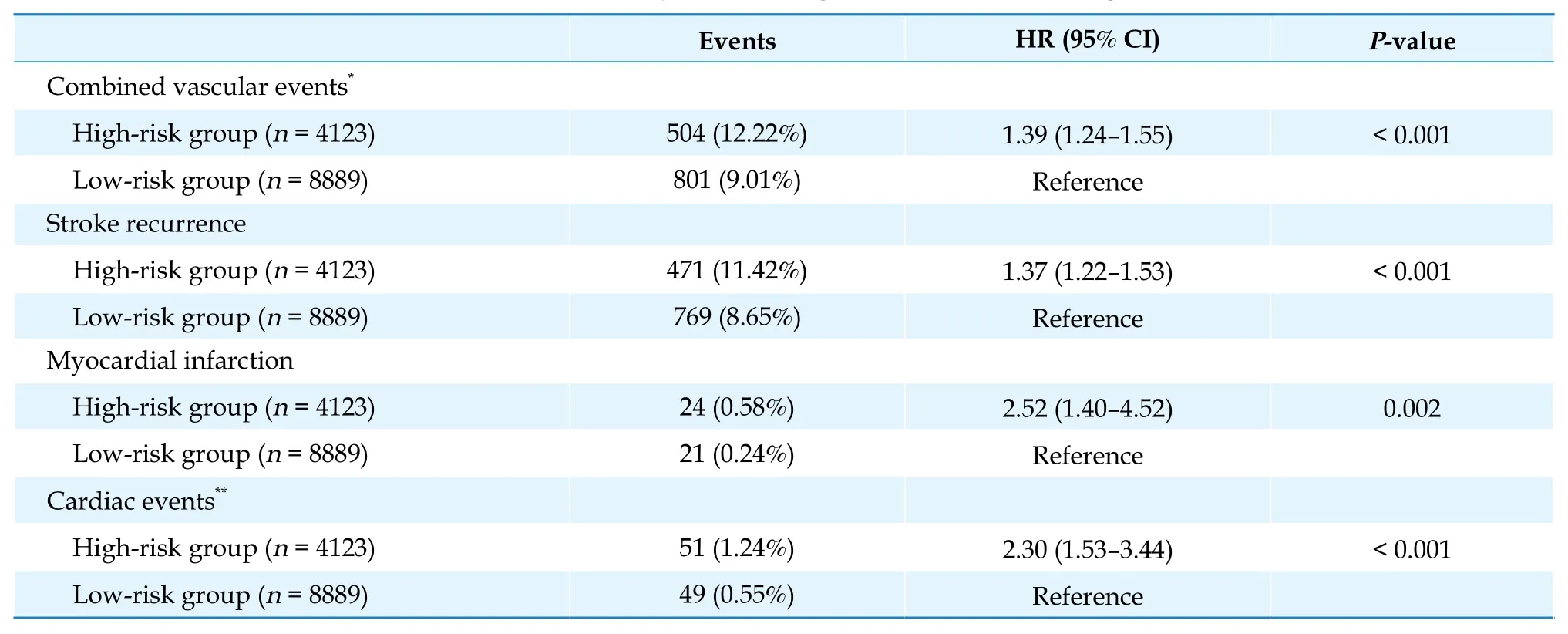

Compared with those with an Essen score < 3, patients with an Essen score ≥ 3 were more likely to have a subsequent combined vascular event [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.24?1.55]and recurrent stroke(HR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.22?1.53). Compared with those with an Essen score < 3, patients with an Essen score ≥3 were associated with a greater than 2-fold risk of cardiac events at one year (HR = 2.30, 95% CI: 1.53-3.44) and MI (HR = 2.52, 95% CI: 1.40?4.52; Table 2).

In addition, the Essen score had low predictive accuracy for combined vascular events with a Cstatistic of 0.56 (95% CI: 0.54-0.57). The Essen score tended to be more predictive for the risk of cardiac events (C-statistic = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.56-0.67) and MI(C-statistic = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.55-0.71) than for the risk of recurrent stroke (C-statistic = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.54-0.57) and combined vascular events (C-statistic = 0.56,95% CI: 0.54-0.57; Table 3).

In multivariable Cox regression analysis including all variables of the Essen score, previous stroke/TIA were the most predictive clinical factors of combined vascular events (adjusted HR = 1.55, 95% CI:1.38-1.73) followed by peripheral artery disease (adjusted HR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.13-1.50), age > 75 years(adjusted HR for the comparison of age < 65 years =1.25, 95% CI: 1.07-1.45), and diabetes mellitus (adjusted HR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.05-1.32). Other cardiovascular diseases (adjusted HR = 2.36, 95% CI: 1.29-4.30)were associated with a greater than 2-fold risk of cardiac events (supplemental material, Table 3S).

Stroke Subtype and Imaging Findings in the Prediction of Vascular Outcomes

In the full Cox regression model including the Essen score, NIHSS score, cause of stroke and neuroimaging findings, LAA (adjusted HR for the comparison with undetermined cause = 1.30, 95% CI:1.14-1.48,P< 0.001), MAI (adjusted HR for the comparison with no acute infarctions = 1.37, 95% CI:1.21-1.54,P= 0.001) and SAI (adjusted HR for the comparison with no acute infarctions = 1.79, 95% CI:1.15-1.36,P< 0.001) were associated with an increased risk of combined vascular events (Table 4).

Figure 1 Distribution of Essen score and one-year combined vascular events or cardiac events stratified by the Essen score categories. (A): Cumulative distribution of Essen score; (B): one-year combined vascular events stratified by the Essen score categories; and(C): one-year cardiac events stratified by the Essen score categories.

Table 2 Events at one year according to Essen score risk categories.

Table 3 Predictive value of the Essen score for outcomes at one year.

Table 4 Logistic regression for combined vascular events at one year in the full model.

The results were similar when further introducing the above parameters as binary variables (Table 5).Moreover, acute infarctions as a binary variable had a higher HR for combined vascular events than MAI as a binary variable. In addition, we investigated whether a combination of acute infarctions (positive DWI)and LAA subtype could improve the predictive value.A total of 1201 patients (9.7%), 328 patients (2.5%),8320 patients (63.9%) and 3103 patients (23.9%) had no infarction without LAA, no infarction with LAA,acute infarctions without LAA and acute infarctions with LAA, respectively.

In the final Model 3 (including Essen score, NIHSS score, no infarction with LAA, acute infarctions without LAA and acute infarctions with LAA), both the Essen score and NIHSS score as binary variables were independent predictors of combined vascular events. Compared with those without infarction or LAA, patients with both acute infarctions and LAA were associated with an approximately 2-fold risk of combined vascular events at one year (adjusted HR = 2.37, 95% CI: 1.81-3.09,P< 0.001).

Adding the variable presence of LAA and acute infarctions as a categorical variable to the Essen score did not significantly increase the predictive value of the Essen score for the risk of combined vascular events (C-statistic = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.55-0.59;supplemental material, Table 4S).

In the full Cox regression model including the Essen score, NIHSS score, cause of stroke and neuroimaging findings, only the CE subtype of TOAST classification was independently associated with an increased risk of one-year cardiac events and MI(Table 6). The results were similar when introducing the above variables as binary variables (Table 7).

DISCUSSION

In a prospective, multicentre, nationwide registry in China, we found that the discriminative ability of the Essen score was low to moderate with C-statistic ranging between 0.56 and 0.63 for selected vascular outcomes. In addition, the Essen score also tended to be more predictive for the risk of MI and cardiac events than that of combined vascular events. Secondly, the rate of combined vascular events and cardiac events increased for patients from lower to higher Essen score categories with acceptable calib-ration. The goodness-of-fit test also showed similar results. Thirdly, we found that acute DWI abnormalities, either acute infarctions or MAIs, and LAA subtype were significantly associated with the risk of combined vascular events. More importantly,imaging findings might provide more predictive value beyond the Essen score and NIHSS score.

Table 5 Logistic regression for combined vascular events at one year in the full model when introducing all variables as binary variables.

Table 6 Logistic regression for cardiac events at one year in the full model.

Table 7 Logistic regression for cardiac events at one year in the full model.

Clinical prediction scores, including the Essen score, Stroke Prognosis Instrument II and ABCD2,for stroke stratification had poor performance on discrimination and calibration.[3,18]Neuroimaging,vascular imaging and cause of stroke were confirmed to provide incremental prognostic value in minor ischaemic stroke or TIA.[6]For instance, the ABCD3I score based on the ABCD2 score and imaging findings demonstrated improved accuracy.[10,19,20]The Essen score, acute infarctions on brain imaging,and TOAST classification have been previously reported to be associated with recurrence stroke.[3,6,7]Liu,et al.[21]demonstrated that the Essen score could stratify the risk of both recurrent stroke and major vascular events within one year in patients with LAA subtype of nonatrial fibrillation stroke but had low prediction power for patients with small-artery subtype of nonatrial fibrillation stroke. A similar result of LAA was also found.[22]MAIs are usually related to an embolic pathogenesis, which could indicate a relatively unstable cause associated with increased vascular risk. Two recent reviews also suggested that acute infarction numbers (mostly MAI) and LAA are associated with an increased risk of recurrent ischaemic stroke.[3,7]As in our study,patients with MAIs or SAIs and LAA had a higher risk of combined vascular events. Moreover, a combination of LAA and acute infarctions was associated with more than a doubling of the risk (adjusted HR = 2.37, 95% CI: 1.81-3.09,P< 0.001).

The modified Essen score (original Essen score plus LAA) increased the ability of the original Essen score to predict recurrence after ischaemic stroke at one year.[23,24]However, adding LAA and acute infarctions to the Essen score did not significantly increase the predictive value for combined vascular events in this study given the poor discriminability of the original Essen score. Considering that LAA and acute infarctions were independent predictors of combined vascular events in the full model, future predictive tools should be developed based on imaging findings, not clinical findings. In fact, a new imaging-based score was developed and validated to predict the early risk of recurrent stroke after ischaemic stroke.[25,26]

In patients with ischaemic stroke or TIA without prior CAD, few scores have been confirmed with the ability to estimate the risk of MI (Framingham score),[27]and to identify asymptomatic CAD (PRECORIS score).[28]However, these two scores only focused on short-term risk, and their discriminative power was poor. In a recent study with more than ten years of follow-up, the Essen score could identify subsets who may be at sufficiently high risk of MI to justify more intensive treatment. In addition, the predictive value is higher for MI than for recurrent stroke.[5]Our study found that the Essen score could predict not only MI but also composite cardiac events. Moreover, patients with an Essen score ≥ 3 identified a high-risk group that had over 2-fold risk of cardiac events and MI compared with those with an Essen score of 0 to 2.

A previous study investigated the capacity of several established prognostic scores (including ABCD2,ABCD2I, ABCD3I, Essen score, California risk score and Stroke Prognosis Instrument) to identify future MI after TIA.[29]Among them, the Essen score had the highest predictive value with a C-statistic of 0.71(95% CI: 0.63-0.79). In addition, positive DWI was independently associated with MI and should be considered in new prediction models. Although patients with TIA constituted only a small proportion of our study population, the Essen score had a moderate predictive value for MI (C-statistic = 0.63,95% CI: 0.55-0.71). MAI indicates an embolic mechanism that portends a high risk of heart diseases.[29]However, positive DWI (MAI or nonacute infarction) was not associated with MI in the current analysis, which might be attributed to the limited number of positive outcomes (45 MI). A recent study showed that the predictive value of the Essen score for MI was similar for patients with different stroke/TIA TOAST subtypes. However, our study found that the Essen score for predicting cardiac events performed better in CE subtypes. Further validation based on large studies is required.

LIMITATIONS

There were some mentionable limitations of this study. Firstly, given that this is a hospital-based registry and the study sites were selected from hospitals with relatively greater medical resources, generalizability is limited. However, the study sites were located in 22 provinces and four municipalities, and the steering committee attempted to ensure nationwide representation of the sample from each area in mainland China. Secondly, of the 15,166 patients, 2154 patients who lacked baseline MRI were excluded.Baseline characteristics were similar between the included patients and excluded patients. Last but not least, follow-up was incomplete for some patients at one year, and 303 patients (2.3%) were lost to follow-up.However, the Kaplan-Meier estimate rate was used for risk estimates.

CONCLUSIONS

The Essen score seems to be more suitable for riskstratification of cardiovascular events than cerebrovascular events. Moreover, future predictive tools should take brain imaging and cause of stroke into consideration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (D1711000 03017002), and the National Science and Technology Major Project (2016YFC0901001 & 2016YFC0901002& 2017ZX09304018). All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors thank the patients who participated in the Third China National Stroke Registry and the contributions of the participating centers.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2022年4期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2022年4期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Ambulatory diastolic blood pressure: a marker of comorbidity in elderly fit hypertensive individuals?

- Pre-hospital delay in patients with acute myocardial infarction in China: findings from the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-Acute Coronary Syndrome (CCC-ACS) project

- Tongmai Yangxin Pill combined with metoprolol or metoprolol alone for the treatment of symptomatic premature ventricular complex: a multicenter, randomized, parallel-controlled clinical study

- Trends and sex differences in atrial fibrillation hospitalization and catheter ablation at tertiary hospitals in China from 2013 to 2016

- Implication of a novel truncating mutation in titin as a cause of autosomal dominant left ventricular noncompaction

- Invasive versus non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring of heart failure patients and their outcomes